Finding Voice: a Visual Arts Approach to Engaging Social Change, Kim S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Online Cultural Mobility Funding Guide for AFRICA

An online cultural mobility funding guide for AFRICA — by ART MOVES AFRICA – Research INSTITUT FRANÇAIS – Support ON THE MOVE – Coordination Third Edition — Suggestions for reading this guide: We recommend that you download the guide and open it using Acrobat Reader. You can then click on the web links and consult the funding schemes and resources. Alterna- tively, you can also copy and paste the web links of the schemes /resources that interest you in your browser’s URL field. This guide being long, we advise you not to print it, especially since all resources are web-based. Thank you! Guide to funding opportunities for the international mobility of artists and culture professionals: AFRICA — An online cultural mobility funding guide for Africa by ART MOVES AFRICA – Research INSTITUT FRANÇAIS – Support ON THE MOVE – Coordination design by Eps51 December 2019 — GUIDE TO FUNDING OPPORTUNITIES FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MOBILITY OF ARTISTS AND CULTURE PROFESSIONALS – AFRICA Guide to funding opportunities for the international This Cultural Mobility Funding Guide presents a mapping of mobility of funding opportunities for interna- tional cultural mobility, focused artists and culture on the African continent. professionals The main objective of this cul- tural mobility funding guide is to AFRICA provide an overview of the fund- ing bodies and programmes that support the international mobility of artists and cultural operators from Africa and travelling to Africa. It also aims to provide input for funders and policy makers on how to fill the existing -

Traveling Suitcase Activations-Joburg WG

Johannesburg Working Group The main case study/story of the The Johannesburg Research Group is a focus on the work of the Medu Art Ensemble (1977 - 1985) Our research story/starting theses/theories informing study/research questions are across three research strings, namely, 1) travelling concepts, 2) radical models of arts education of the 1970s and 3) the activation of historical experiences in claiming histories. The central string is that of radical models of arts education. The project exists as part of a wider recuperative project that seeks to map histories of arts education in southern Africa with the view to producing a more comprehensive understanding of how imported colonial models have come to assert a particular understanding of “arts education” that has often marginalised or attempted to erase the presence of existing local models. The research group aims to demonstrate the active presence of a series of local models that challenge the hegemonic status of imported models. Here we take our cue from Eduard Glissant’s understanding of histories as: The history you ignored – or didn’t make – was it not history? (The complex and mortal anhistorical). Might you not be more and more affected by it, in your fallowness as much as in your harvest? In your thought as much as in your will? Just as I was affected (cit) by the history I wasn’t making, and could not ignore? (1969, 23) In an earlier document the Johannesburg Research Group described its focus in the following ways: The Johannesburg Working group finds resonance in the themes and aims of the international cluster project, ‘Histories’ which are broadly; modes of ‘inhabiting’ histories, history as a ‘resource’, disturbing hegemonial narratives of history and animating, activating counter-hegemonial narratives. -

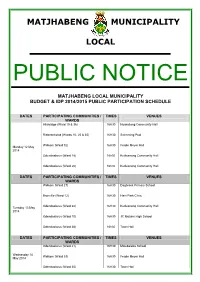

Matjhabeng Municipality Local

MATJHABENG MUNICIPALITY LOCAL PUBLIC NOTICE MATJHABENG LOCAL MUNICIPALITY BUDGET & IDP 2014/2015 PUBLIC PARTICIPATION SCHEDULE DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Allanridge (Ward 19 & 36) 16H30 Nyakallong Community Hall Riebeeckstad (Wards 10, 25 & 35) 16H30 Swimming Pool Welkom (Ward 32) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall Monday 12 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 18) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Odendaalsrus (Ward 20) 16h30 Kutlwanong Community Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Welkom (Ward 27) 16H30 Dagbreek Primary School Bronville (Ward 12) 16H30 Hani Park Clinic Odendaalsrus (Ward 22) 16H30 Kutlwanong Community Hall Tuesday 13 May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 10) 16H30 JC Motumi High School Odendaalsrus (Ward 36) 16h30 Town Hall DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Odendaalsrus (Ward 21) 16H30 Malebaleba School Wednesday 14 Welkom (Ward 33) 16H30 Ferdie Meyer Hall May 2014 Odendaalsrus (Ward 35) 16H30 Town Hall Bronville (Ward 11) 16H30 Bronville Community Hall Welkom (Ward 24) 16H30 Reahola Housing Units DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Bronville (Ward 23) 16H30 Hani Park Church Thabong (Ward 12) 16H30 Tsakani School Thursday 15 May Thabong (Ward 30) 16H30 Thabong Primary School 2014 Thabong (Ward 31) 16H30 Thabong Community Centre Thabong (Ward 28) 16H30 Thembekile School DATES PARTICIPATING COMMUNITIES / TIMES VENUES WARDS Thabong (Ward 26) 16H30 Bofihla School Thabong (Ward 29) 16H30 Lebogang School Monday 19 May 2014 Thabong Far East (Ward 25) 16H30 Matshebo School -

Udr 116 43.Pdf

Featu re-fi lied page 2 Late night fitness center - cravings ... \IELE!j opens _ page 13 \. THE EVIEWA FOUR-STAR A _LL-AMERICAN NEWSPAPER TUESDAY Students fight to save Wolf Hall stage By Jennifer McCann Campus groups say Newark Hall theater not an adequate alternative Wolf Hall is in poor condition. and Sharon O'Neal "It's not a good lecture hall. It's not a StaH Reporters without removing its stage. prod uce for fa ll semester. coordinator, said, "If we don't have Wolf good performance space," Hollowe ll said. DUSC President Jeff Thomas (BE 90) Dav id E. Hollowell , senior vice president Hall to perfonn in, then I don't think there "The issue is whether we can usc Wolf Hall The Delaware Undergraduate Student said the groups plan to examine classroom for Administration, said th e administration will be anymore student theater on for both purposes." Congress (DUSC) and two student theater theater spaces at other schools to show I 00 has seen enough student concern that it is campus." E-52 and HTAC are two of the most groups will launch a campaign today, "Save Wolf Hall can be used for both purposes. "worth taking another look at. If we can get active student organizations, Thomas said. Wolf Stage," to prevent planned They also plan to advertise the cause to th e double space out of Wolf Ha ll , we'll see editorial page 6 He said 12,609 people attended 22 shows renovations which would remove the stage campus community, send concern letters to certainly try to do that. -

Pressemitteilung Zu Lisa Stansfield

Pressemitteilung zu Lisa Stansfield Lisa Stansfield spielt ihr neues Album „Deeper“ und all ihre weltbekannten Hits am 05.05.18 im Hamburger Mehr! Theater live Hamburg, Oktober 2017 – Mit Songs ihres kommenden Albums „Deeper“ plus vielen ihrer gefeierten Hits meldet sich Lisa Stansfield nach vier Jahren zurück auf deutschen Bühnen! Die globale Soul-Botschafterin, die sich 1989 mit dem Welthit „All Around The World“ ins weltweite Musikgedächtnis spielte, gastiert am 05.05.18 im Mehr! Theater in Hamburg! Für ihre Tour 2018 verspricht die Grammy-Gewinnerin nicht nur geballte Bühnenpower, sondern auch ein exquisites Programm: Im Fokus stehen neben den Bestsellern „All Around The World“, „This Is The Right Time“, The Real Thing“, „8-3-1“, „Let’s Just Call It Love“ oder „If I Hadn’t Got You“ Songs ihres ersten neuen Albums seit 2014. Auf „Deeper“ (earMUSIC/edel, VÖ: Frühjahr 2018), ihrer achten Studio-CD, pflegt die mit diversen Brit- Awards ausgezeichnete Künstlerin jene Tugenden, die aus der jugendlichen Talentwettbewerb-Teilnehmerin einen Star von internationalem Format haben werden lassen: Pop, Jazz, Dance, Motown und Northern Soul verschmelzen, getragen von der voluminösen, facettenreichen Stimme der zierlichen Mrs. Stansfield, zu funky groovenden Pressekontakt: Erik Sabas +49 40 4133018-40 [email protected] river_concerts www.riverconcerts.de River Concerts Disco-Tracks, wohl temperierten Soul-Pop-Balladen sowie entspannten Easy-Listening- Songs. Diese „mit Eleganz und Sex-Appeal vorgetragenen pechschwarzen Klänge“ können bei den „Gänsehaut erzeugenden Konzerten“ (‚Berliner Morgenpost‘) in bestuhlten Hallen live genossen werden. Live ist die Künstlerin, die als Vokalistin des mit dem Dancefloor-Duo Coldcut eingespielten Hits „People Hold On“ ihre musikalische Laufbahn startete, ein Ereignis. -

Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg

CENTRE FOR DEVELOPMENT SUPPORT SENTRUM VIR ONTWIKKELINGSTEUN ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Lead authors: Lochner Marais (University of the Free State) Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Case study authors: Drakenstein: Ronnie Donaldson (Stellenbosch University) King Sabata Dalindyebo: Esethu Ndzamela (Nelson Mandela University) and Anton De Wit (Nelson Mandela University Lephalale: Kgosi Mocwagae (University of the Free State) Matjhabeng: Stuart Denoon-Stevens (University of the Free State) Mahikeng: Verna Nel (University of the Free State) and James Drummond (North West University) Mbombela: Maléne Campbell (University of the Free State) Msunduzi: Thuli Mphambukeli (University of the Free State) Polokwane: Gemey Abrahams (independent consultant) Rustenburg: John Ntema (University of South Africa) Sol Plaatje: Thomas Stewart (University of the Free State) Stellenbosch: Danie Du Plessis (Stellenbosch University) Manager: Geci Karuri-Sebina Editing by Write to the Point Design by Ink Design Photo Credits: Page 2: JDA/SACN Page 16: Edna Peres/SACN Pages 18, 45, 47, 57, 58: Steve Karallis/JDA/SACN Page 44: JDA/SACN Page 48: Tanya Zack/SACN Page 64: JDA/SACN Suggested citation: SACN. 2017. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? South African Cities Network: Johannesburg. Available online at www.sacities.net ISBN: 978-0-6399131-0-0 © 2017 by South African Cities Network. Spatial Transformation: Are Intermediate Cities Different? is made available under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/. 2 SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION: ARE INTERMEDIATE CITIES DIFFERENT? Foreword As a network whose primary stakeholders are the largest cities, the South African Cities Network (SACN) typically focuses its activities on the “big” end of the urban spectrum (essentially, mainly the metropolitan municipalities). -

Exploring the Relationship Between the Strong Black Woman Archetype and Mental Health Help-Seeking Behaviors of Black

CRANES IN THE SKY: EXPLORING THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE STRONG BLACK WOMAN ARCHETYPE AND MENTAL HEALTH HELP-SEEKING BEHAVIORS OF BLACK WOMEN A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE TEXAS WOMAN’S UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF SOCIOLOGY AND SOCIAL WORK COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES BY MIA M. KIRBY B.S., M.S.W., LCSW DENTON, TEXAS MAY 2019 Copyright © 2019 by Mia Moore Kirby DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my ancestors and spirit guides Joseph B. Provost Sr. Mary Louise Dorn Jackson James Lamar Provost Wilbur Daniel Moore Thank you for always being with me. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I must acknowledge The Creator, through which all blessings flow. I could not have embarked on this journey without the presence of the Lord in my life, Ashé. It wasn’t until I was deeply ingrained in the research that I realize that this work is a physical embodiment of my upbringing. To this end, I must thank my parents, my mother Janice Provost, for being the original strong black women in my life, who demonstrated strength through healing. I can never repay you for the seeds of healing and growth that you planted in me. To my father, Dexter Moore, the first DJ I ever knew. You have always been one of my biggest supporters. I am so grateful for your wisdom and guidance throughout my life and most importantly for always playing my favorite songs. To my husband, Dr. Darian T. Kirby, I am beyond grateful for your love, support, and encouragement. -

Mean Streets: Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa

Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Published by the Southern African Migration Programme (SAMP), the African Centre for Cities (ACC) and the International Development Research Centre (IDRC) Southern African Migration Programme, International Migration Research Centre Balsillie School of International Affairs, 67 Erb Street West, Waterloo, Ontario N2L 6C2, Canada African Centre for Cities, University of Cape Town, Environmental & Geographical Science Building, Upper Campus, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa International Development Research Centre, 160 Kent St, Ottawa, Canada K1P 0B2 and Eaton Place, 3rd floor, United Nations Crescent, Gigiri, Nairobi, Kenya ISBN 978-1-920596-11-8 © SAMP 2015 First published 2015 Production, including editing, design and layout, by Bronwen Dachs Muller Cover by Michiel Botha Cover photograph by Alon Skuy/The Times. The photograph shows Soweto residents looting a migrant-owned shop in a January 2015 spate of attacks in South Africa Index by Ethné Clarke Printed by MegaDigital, Cape Town All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission from the publishers. Mean Streets Migration, Xenophobia and Informality in South Africa Edited by Jonathan Crush Abel Chikanda Caroline Skinner Acknowledgements The editors would like to acknowledge the financial and programming support of the Inter- national Development Research Centre (IDRC), which funded the research of the Growing Informal Cities Project and the Workshop on Urban Informality and Migrant Entrepre- neurship in Southern African Cities hosted by SAMP and the African Centre for Cities in Cape Town in February 2014. Many of the chapters in this volume were first presented at this workshop. -

Guiding People Through Conflict | 1

GUIDING PEOPLE THROUGH CONFLICT | 1 RW360’s vision is that Christians around the world would draw others to Christ by developing relationships that are astonishingly loving, united, joyful, durable, creative and fruitful. RW360’s mission is to equip Christians to develop strong, enduring and appealing relationships that display the love of Jesus Christ and the transforming power of his gospel. We provide educational resources, seminars and training to help churches, seminaries, ministries and businesses around the world. We also provide conflict coaching, mediation and arbitration services to help resolve family conflicts, business disputes, church divisions and lawsuits in a way that restores relationships, promotes j ustice and brings glory to God. 4460 Laredo Place, Billings, MT 59108 406-294-6806 | [email protected] www.rw360.org | www.rw-academy.org This eBook is based on Ken Sande’s book, The Peacemaker: A Biblical Guide to Resolving Personal Conflict (Baker Books, 3rd Ed. 2004). This eBook may be downloaded, printed or electronically shared with others in its entirety for non-commercial purposes. This publication provides general information on biblical conflict resolution, also known as “Christian conciliation.” It is not intended to provide legal or other professional advice. In situations involving complex legal issues, emotional trauma, power imbalances or abuse (physical, emotional, sexual, child, elder, spiritual, etc.), the services of a competent professional person should be sought. Scripture quotations are from the New International -

"6$ ."*@CL9@CJ#L "6&$CG@%LC$ A=-L@68L&@@*>C

1 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA DATE: 2013-10-17 REPORT TO: ADEL GROENEWALD (Enviroworks) Tel: 086 198 8895; Fax: 086 719 7191; Postal Address: Suite 116, Private Bag X01, Brandhof, 9301; E-mail: [email protected] ANDREW SALOMON (South African Heritage Resources Agency - SAHRA) Tel: 021 462 4505; Fax: 021 462 4509; Postal Address: P.O. Box 4637, Cape Town, 8000; E-mail: [email protected] PREPARED BY: KAREN VAN RYNEVELD (ArchaeoMaps) Tel: 084 871 1064; Fax: 086 515 6848; Postal Address: Postnet Suite 239, Private Bag X3, Beacon Bay, 5205; E-mail: [email protected] THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 2 SPECIALIST DECLARATION OF INTEREST I, Karen van Ryneveld (Company – ArchaeoMaps; Qualification – MSc Archaeology), declare that: o I am suitably qualified and accredited to act as independent specialist in this application; o I do not have any financial or personal interest in the application, ’ proponent or any subsidiaries, aside from fair remuneration for specialist services rendered; and o That work conducted has been done in an objective manner – and that any circumstances that may have compromised objectivity have been reported on transparently. SIGNATURE – DATE – 2013-10-17 THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 3 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TERMS OF REFERENCE - Enviroworks has been appointed by the project proponent, Lebone Solar Farm (Pty) Ltd, to prepare and submit the EIA and EMPr for the proposed 75MW photovoltaic (PV) solar facility on the properties Remaining Extent of Farm Onverwag 728 and Portion 2 of Farm Vaalkranz 220 near Welkom in the Free State, South Africa. -

Electrification Infrastructure Projects

Electrification Infrastructure Projects “Do more together with less” Roshan Pillay 24 February 2016 ESKOM Overview Transmission substation Electricity generation Transmission lines Customer Services (765/400/275 kV) Embedded generation Distribution lines 132/88/66kV Industry, mining & large metros Distribution substation Reticulation HV line (11 & 22kV) Reticulation Residential LV line (380/220V) Commercial/small industry/ farming/small munics 2 What are the technical opportunities? Type of service: Minor Distribution Line Construction (11-33kV) Major Distribution Line Construction (11-33kV) Pole Replacement - Dead Conditions Pole Replacement - Live Conditions Electrification Infills Live Work Maintenance 11-33kV - FSOU Live Work Maintenance 44-132kV - FSOU Live Work Maintenance Substations - FSOU 3 What are the technical opportunities? Type of service: SPU Meter Dis connections & Re-connections - FSOU MV and LV Cable repairs and maintenance Emergency Distribution Line Repairs and Maintenance Electrical and Civil Work - FSOU Substations 4 What are the non technical opportunities? Type of service: PPU meter Audits FSOU SPU meter Audits FSOU SPU Meter Readings - FSOU 5 Free State Operating Unit Project Budget • +- R1b for the next 3 years (2016 – 2018) • Categories: • Direct Customers • Strengthening • Refurbishment • Asset Purchases • Electrification Infrastructure Projects: Thabo Mofutsanyana Vrede Memel Petrus Steyn Reitz Warden Bethlehem Harrismith Marquard Clarens Phuthaditjhaba Ficksburg Clocolan Excelsior Ladybrand Tweespruit SIP -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A.