Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential of the Implementation of Demand-Side Management at the Theunissen-Brandfort Pumps Feeder

POTENTIAL OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DEMAND-SIDE MANAGEMENT AT THE THEUNISSEN-BRANDFORT PUMPS FEEDER by KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL In the Faculty of Engineering, Information & Communication Technology: School of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering At the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Mr L Moji, MSc. (Eng) Co- supervisor: Prof. LJ Grobler, PhD (Eng), CEM BLOEMFONTEIN NOVEMBER 2006 i PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com ii DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI, hereby declare that this research project submitted for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL, is my own independent work that has not been submitted before to any institution by me or anyone else as part of any qualification. Only the measured results were physically performed by TSI, under my supervision (refer to Appendix I). _______________________________ _______________________ SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com iii Acknowledgement My interest in the energy management study concept actually started while reading Eskom’s journals and technical bulletins about efficient-energy utilisation and its importance. First of all I would like to thank ALMIGHTY GOD for making me believe in MYSELF and giving me courage throughout this study. I would also like to thank the following people for making this study possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to both my supervisors Mr L Moji and Prof. LJ Grobler who is an expert and master of the energy utilisation concept and also for both their positive criticism and the encouragement they gave me throughout this study. -

Lesleywalker

(3/10/21) LESLEY WALKER Editor FILM & TELEVISION DIRECTOR COMPANIES PRODUCERS “MILITARY WIVES” Peter Cattaneo 42 Rory Aitken Tempo Productions Ltd. Ben Pugh “THE MAN WHO KILLED DON Terry Gilliam Amazon Studios Mariela Besuievsky QUIXOTE” Recorded Picture Co. Amy Gilliam Gerardo Herrero Gabriele Oricchio “THE DRESSER” Richard Eyre BBC Suzan Harrison Playground Ent. Colin Callender “MOLLY MOON: THE Christopher N. Rowley Amber Ent. Lawrence Elman INCREDIBLE HYPNOTIST” Lipsync Prods. Ileen Maisel “HOLLOW CROWN: HENRY IV”Richard Eyre BBC Rupert Ryle-Hodges Neal Street Prods. Sam Mendes “I AM NASRINE” Tina Gharavi Bridge and Tunnel Prods James Richard Baille (Supervising Editor) David Raedeker “WILL” Ellen Perry Strangelove Films Mark Cooper Ellen Perry Taha Altayli “MAMMA MIA” Phyllida Lloyd Playtone Gary Goetzman Nomination: American Cinema Editors (ACE) Award Universal Pictures Tom Hanks Rita Wilson “CLOSING THE RING” Richard Attenborough Closing the Ring Ltd. Jo Gilbert “BROTHERS GRIMM” Terry Gilliam Miramax Daniel Bobker Charles Roven “TIDELAND” Terry Gilliam Capri Films Gabriella Martinelli Recorded Picture Co. Jeremy Thomas “NICHOLAS NICKLEBY” Douglas McGrath Cloud Nine Ent. S. Channing Williams Hart Sharp Entertainment John Hart MGM/United Artists Jeffery Sharp “ALL OR NOTHING” Mike Leigh Cloud Nine Entertainment Simon Channing Williams Le Studio Canal “SLEEPING DICTIONARY” Guy Jenkin Fine Line Simon Bosanquet "FEAR AND LOATHING IN Terry Gilliam Rhino Patrick Cassavetti LAS VEGAS" Stephen Nemeth "ACT WITHOUT WORDS I" Karel Reisz Parallel -

For Southern Africa SHIPPING ADDRESS: POSTAL ADDRESS: Clo HARVARD EPWORTH CHURCH P

International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa SHIPPING ADDRESS: POSTAL ADDRESS: clo HARVARD EPWORTH CHURCH P. 0. Box 17 1555 MASSACHUSETfS AYE. CAMBRIDGE. MA 02138 CAMBRIDGE. MA 02138 TEL (617) 491-8343 BOARD OF TRUSTEES A LETTER FROM DONALD WOODS Willard Johnson, President Margaret Burnham Kenneth N. Carstens John B. Coburn Dear Friend, Jerry Dunfey Richard A. Falk You can save a life ~n South Africa. EXECUTIVE DIRECIDR Kenneth N. E:arstens ..:yOtl- e-an-he-l--p -ave-a h-i-l cl adul-t ~rom the herre-I"s- af a South African prison cell. ASSISTANT DIRECIDR Geoffrey B. Wisner You can do this--and much more--by supporting the SPONSORS International Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa--IDAF. John C. Bennett Lerone Bennett, Jr. Leonard Bernstein How do I know this? Mary F. Berry Edward W. Brooke I have seen the many ways in which IDAF defends political Robert McAfee Brown prisoners and their families in Southern Africa. Indeed, Shirley Chisholm I myself helped to deliver the vital services it provides. Dorothy Cotton Harvey Cox C. Edward Crowther You can be sure that repression in South Africa will not Ronald V. DeHums end until freedom has been won. That means more brutality Ralph E. Dodge by the South African Police--more interrogations, more torture, Gordon Fairweather more beatings, and even more deaths. Frances T. Farenthold Richard G. Hatcher Dorothy 1. Height IDAF is one of the most effective organizations now Barbara Jordan working to protect those who are imprisoned and brutally Kay Macpherson ill-treated because of their belief in a free South Africa. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 18, No. 9

Zimbabwe News, Vol. 18, No. 9 http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.nuzn198709 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Zimbabwe News, Vol. 18, No. 9 Alternative title Zimbabwe News Author/Creator Zimbabwe African National Union Publisher Zimbabwe African National Union (Harare, Zimbabwe) Date 1987-09-00 Resource type Magazines (Periodicals) Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) Zimbabwe, Mozambique, South Africa, Southern Africa (region) Coverage (temporal) 1987 Source Northwestern University Libraries, L968.91005 Z711 v.18 Rights By kind permission of ZANU, the Zimbabwe African National Union Patriotic Front. Description Editorial. Address to the Central Committee by the President and First Secretary of ZANU (PF) Comrade R.G. -

Public Libraries in the Free State

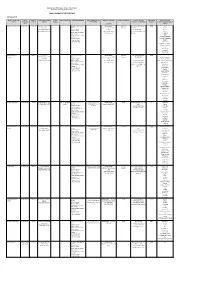

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

Cry Freedom Essay

L.B. History Period 7 Feb. 2003 Cry Freedom; Accurate? Have you ever seen a movie based on a true story and wondered if it was truly and completely accurate? Many movies and books documenting historical lives and events have twisted plots to make the story more interesting. The movie Cry Freedom, directed by Richard Attenborough, is not one of these movies; it demonstrates apartheid in South Africa accurately through the events in the lives of both Steve Biko and Donald Woods. Cry Freedom has a direct relation to black history month, and has been an influence to me in my feelings about racism and how it is viewed and dealt with today. Cry Freedom was successful in its quest to depict Steve Biko, Donald Woods, and other important characters as they were in real life. Steve Biko was a man who believed in justice and equality for all races and cultures. The important points in his life such as his banning (1973), his famous speeches and acts to influence Africans, the trial (convicting the nine other black consciousness leaders) in which he took part, his imprisoning and ultimately his death were documented in Cry Freedom, and they were documented accurately. Steve Biko was banned by the South African Apartheid government in 1973. Biko was restricted to his home in Kings William's Town in the Eastern Cape and could only converse with one person at a time, not including his family (The History Net, African History http://africanhistory.about.com/library/biographies/blbio-stevebiko.htm). In the movie, this is shown when Biko first meets Donald Woods where he explains his banning situation. -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society. -

Free State Provincial Government

FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT “A prosperous and equitable Free State Province through safe and efficient transport and infrastructure systems” Department of Public Works, Roads and Transport: Generic Strategic Plan 2003/2004 – 2005/2006 TABLE OF CF CONTENTS 1 POLICY STATEMENT..............................................................................................................4 2 OVERVIEW BY THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER..................................................................6 3 VISION.........................................................................................................................................7 4 MISSION......................................................................................................................................7 5 VALUE SYSTEM........................................................................................................................7 6 LEGISLATIVE AND OTHER MANDATES ...........................................................................8 7 DESCRIPTION OF THE STATUS QUO................................................................................9 8 DESCRIPTION OF STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS ...............................................13 9 DEPARTMENTAL STRATEGIC GOALS AND STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES...............15 10 MEASURABLE OBJECTIVES, OUTPUTS AND PERFORMANCE MEASURES ..17 10.1 PROGRAMME 1: CORPORATE SERVICES DIRECTORATE ......................... 17 10.2 PROGRAMME 2: ORGANISATIONAL DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE... 23 10.3 PROGRAMME 3: WORKS INFRASTRUCTURE.............................................. -

"6$ ."*@CL9@CJ#L "6&$CG@%LC$ A=-L@68L&@@*>C

1 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA DATE: 2013-10-17 REPORT TO: ADEL GROENEWALD (Enviroworks) Tel: 086 198 8895; Fax: 086 719 7191; Postal Address: Suite 116, Private Bag X01, Brandhof, 9301; E-mail: [email protected] ANDREW SALOMON (South African Heritage Resources Agency - SAHRA) Tel: 021 462 4505; Fax: 021 462 4509; Postal Address: P.O. Box 4637, Cape Town, 8000; E-mail: [email protected] PREPARED BY: KAREN VAN RYNEVELD (ArchaeoMaps) Tel: 084 871 1064; Fax: 086 515 6848; Postal Address: Postnet Suite 239, Private Bag X3, Beacon Bay, 5205; E-mail: [email protected] THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 2 SPECIALIST DECLARATION OF INTEREST I, Karen van Ryneveld (Company – ArchaeoMaps; Qualification – MSc Archaeology), declare that: o I am suitably qualified and accredited to act as independent specialist in this application; o I do not have any financial or personal interest in the application, ’ proponent or any subsidiaries, aside from fair remuneration for specialist services rendered; and o That work conducted has been done in an objective manner – and that any circumstances that may have compromised objectivity have been reported on transparently. SIGNATURE – DATE – 2013-10-17 THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 3 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TERMS OF REFERENCE - Enviroworks has been appointed by the project proponent, Lebone Solar Farm (Pty) Ltd, to prepare and submit the EIA and EMPr for the proposed 75MW photovoltaic (PV) solar facility on the properties Remaining Extent of Farm Onverwag 728 and Portion 2 of Farm Vaalkranz 220 near Welkom in the Free State, South Africa. -

First Phase Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Assessment of the Proposed Borrow Pit Sites Along the R30 Main Road Between Brandfort & Vet River, Free State

28 February 2007 FIRST PHASE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED BORROW PIT SITES ALONG THE R30 MAIN ROAD BETWEEN BRANDFORT & VET RIVER, FREE STATE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Several borrow pits intended for use during the upgrading of the R30 main road between Brandfort and Theunissen, Free State, was investigated. Most of the quarries will be extensions of existing borrow pits and contain no cultural or historical material. Graves occur near two of the sites and should be avoided during excavations. I recommend that the proposed development and planning of the sites may proceed. INTRODUCTION AND DESCRIPTION INVESTIGATION Borrow pits for the upgrading of the R30 main road between Brandfort and Theunissen, were visited on 5 January 2007. Dr Johan du Preez of MDA Environmental Consultants, Bloemfontein, took me to the sites. The area was examined for possible archaeological and historical material and to establish the potential impact on any cultural material that might be found. The Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) is done in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA), (25 of 1999) and under the Environmental Conservation Act, (73 of 1989). 2 LOCALITY Nine borrow pits were investigated along the R30 main road between Brandfort and the Beatrix Mine turn-off near Theunissen, Free State (Map 2). GPS coordinates (Cape scale) are given below: BP km 7,7 at Masjwemasweu, Brandfort. (Map 3). The site contains an existing quarry (Fig.1). 28°40’31”S 026°28’05”E Altitude 1436m. BP km 15,3 Borrow pit on the farm Biesiebult 90 along the R30 main road between Brandfort and Theunissen.