Ronald M. Segal Jan.-March 1959 Contents Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Potential of the Implementation of Demand-Side Management at the Theunissen-Brandfort Pumps Feeder

POTENTIAL OF THE IMPLEMENTATION OF DEMAND-SIDE MANAGEMENT AT THE THEUNISSEN-BRANDFORT PUMPS FEEDER by KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI Dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL In the Faculty of Engineering, Information & Communication Technology: School of Electrical & Computer Systems Engineering At the Central University of Technology, Free State Supervisor: Mr L Moji, MSc. (Eng) Co- supervisor: Prof. LJ Grobler, PhD (Eng), CEM BLOEMFONTEIN NOVEMBER 2006 i PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com ii DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENT WORK I, KHOTSOFALO CLEMENT MOTLOHI, hereby declare that this research project submitted for the degree MAGISTER TECHNOLOGIAE: ENGINEERING: ELECTRICAL, is my own independent work that has not been submitted before to any institution by me or anyone else as part of any qualification. Only the measured results were physically performed by TSI, under my supervision (refer to Appendix I). _______________________________ _______________________ SIGNATURE OF STUDENT DATE PDF created with pdfFactory trial version www.pdffactory.com iii Acknowledgement My interest in the energy management study concept actually started while reading Eskom’s journals and technical bulletins about efficient-energy utilisation and its importance. First of all I would like to thank ALMIGHTY GOD for making me believe in MYSELF and giving me courage throughout this study. I would also like to thank the following people for making this study possible. I would like to express my sincere gratitude and respect to both my supervisors Mr L Moji and Prof. LJ Grobler who is an expert and master of the energy utilisation concept and also for both their positive criticism and the encouragement they gave me throughout this study. -

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting

Remembrance African Activist Archive Project Documenting Apartheid: 30 Years of Filming South Africa By Peter Davis During April 2004 and beyond we were constantly reminded that this is the tenth anniversary of the first democratic all-race elections in South Africa. I was shocked by the realization that last year also marked the thirtieth anniversary of my first visit to that country, of my first experience with apartheid. After that first trip in 1974 as part of an African tour I was doing for the American NGO, Care, I was to devote a large part of my working life to the anti-apartheid struggle. For those of us who were involved in that struggle, it was such an everyday part of life that it is hard to grasp that there is already a generation out there that does not know the meaning of “apartheid”. The struggle against apartheid took many forms, from protests, strikes, sabotage, defiance, guerrilla warfare within the country to boycotts, bans, United Nations resolutions, rock concerts, and arms and money smuggling and espionage outside. Apartheid, which was institutionalized by the coming to power of the white National Party in 1948, lasted as long as it did, against the condemnation of the world, because it had powerful friends. Chief among these were the United States, which saw a South Africa governed by whites as a useful ally in the Cold War; a Britain whose ruling class had close links with South African capital; and German, French, Israeli and Taiwanese commercial interests that extended even to sales of weapons and nuclear technology to the apartheid regime. -

A Short History of Amabhele

A Short History of AmaBhele As a clan, amaBhele have a long and vast history, which links them to other various Nguni language-speaking groups who are understood to have once lived in the central African region many centuries ago before they set on a long southward migration until they eventually settled along the east coast of what is now known as South Africa. This discussion serves as a short summary of this vast history. The main emphasis is on the period from the late 1700s and early-to-mid- 1800s when the clan was divided (or got separated) into numerous sections thereafter; and highlights how they were differently affected by the course of history from that period. As is customary with other Nguni clans, amaBhele got their clan name from one particular ‘Bhele’ who lived approximately four centuries ago. Not much information is known about ‘Bhele’ himself - except that the members of “Bhele’s” family later became known as amaBhele, and that they later grew and expanded to become a large clan. It is to the same ‘Bhele’ that abakwaNtshangase (distinct from Ntshangase/Mgazi), abakwaKhuboni and abakwaShabangu, respectively, also trace their descent. The circumstances around which these three above-mentioned sections separated from their parent clan, amaBhele, are not known. It is probably that there are other surnames that also historically derived from amaBhele (or ‘Bhele’). But for the purposes of this brief summary only these three are mentioned at this point because information concerning them is easy to verify and trace through a careful analysis of the information obtained from traditional African oral history pending a more in-depth inquiry. -

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report: Volume 2

VOLUME TWO Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa Report The report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was presented to President Nelson Mandela on 29 October 1998. Archbishop Desmond Tutu Ms Hlengiwe Mkhize Chairperson Dr Alex Boraine Mr Dumisa Ntsebeza Vice-Chairperson Ms Mary Burton Dr Wendy Orr Revd Bongani Finca Adv Denzil Potgieter Ms Sisi Khampepe Dr Fazel Randera Mr Richard Lyster Ms Yasmin Sooka Mr Wynand Malan* Ms Glenda Wildschut Dr Khoza Mgojo * Subject to minority position. See volume 5. Chief Executive Officer: Dr Biki Minyuku I CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 6 National Overview .......................................... 1 Special Investigation The Death of President Samora Machel ................................................ 488 Chapter 2 The State outside Special Investigation South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 42 Helderberg Crash ........................................... 497 Special Investigation Chemical and Biological Warfare........ 504 Chapter 3 The State inside South Africa (1960-1990).......................... 165 Special Investigation Appendix: State Security Forces: Directory Secret State Funding................................... 518 of Organisations and Structures........................ 313 Special Investigation Exhumations....................................................... 537 Chapter 4 The Liberation Movements from 1960 to 1990 ..................................................... 325 Special Investigation Appendix: Organisational structures and The Mandela United -

Public Libraries in the Free State

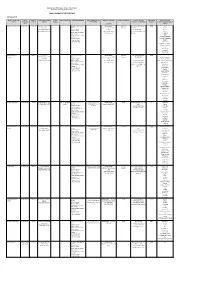

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society. -

Free State Provincial Government

FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT “A prosperous and equitable Free State Province through safe and efficient transport and infrastructure systems” Department of Public Works, Roads and Transport: Generic Strategic Plan 2003/2004 – 2005/2006 TABLE OF CF CONTENTS 1 POLICY STATEMENT..............................................................................................................4 2 OVERVIEW BY THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER..................................................................6 3 VISION.........................................................................................................................................7 4 MISSION......................................................................................................................................7 5 VALUE SYSTEM........................................................................................................................7 6 LEGISLATIVE AND OTHER MANDATES ...........................................................................8 7 DESCRIPTION OF THE STATUS QUO................................................................................9 8 DESCRIPTION OF STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS ...............................................13 9 DEPARTMENTAL STRATEGIC GOALS AND STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES...............15 10 MEASURABLE OBJECTIVES, OUTPUTS AND PERFORMANCE MEASURES ..17 10.1 PROGRAMME 1: CORPORATE SERVICES DIRECTORATE ......................... 17 10.2 PROGRAMME 2: ORGANISATIONAL DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE... 23 10.3 PROGRAMME 3: WORKS INFRASTRUCTURE.............................................. -

CONTINUITY and CHANGE in CISXEI CHIFZSHIP by J. B. Peires the Conventional Wisdom of South African Ethnologists, Whether Liberal

CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN CISXEI CHIFZSHIP by J. B. Peires The conventional wisdom of South African ethnologists, whether liberal or conservative, has been dominated by the idea that African polities operated according to certain fixed rules (tlcustomsw)which were hallowed by tradition and therefore never chaaged. (1) A corolla-ry of this is that, if these rules could be correctly identified and fairly applied, everyone would be satisfied and chiefship could perhaps be saved. (2) It is, however, fairly well established that genealogies are often falsified, that new rules are coined and old rules bent to accommodate changing configurations of power, and that "age-old" customs may turn out to be fairly recent innovations; in short, that "organisational ideas do not directly control action, but only the interpretation of actionr1.(3) This conventional wisdom was successfully challenged by Comaroff in an important article, Itchiefship in a South African Homelandt1,which demonstrated that, by adhering too closely to the formal features of traditional government and politics among the Tswana, especially those concerning succession, the Government wrecked the political processes which had enabled the 'Pswam to choose the most suitable candidate as chief. (4) And yet Comarofffs article begs a good many questions. Let us imagine that the Government ethnologists read the article, and as a result allow Tswana chiefs to compete for office as before, permitting flconsultativedecision-making and participation in executive processes". (5) Would this prevent the Tswana chiefship from dying? Can we, in fact, discuss chiefship in political terms alone without considering whether the material conditions in which it flourished still exist? The present article will attempt to situate the question of chiefship in a somewhat wider framework than that usually provided by administrative theory or transactional analysis. -

"6$ ."*@CL9@CJ#L "6&$CG@%LC$ A=-L@68L&@@*>C

1 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA DATE: 2013-10-17 REPORT TO: ADEL GROENEWALD (Enviroworks) Tel: 086 198 8895; Fax: 086 719 7191; Postal Address: Suite 116, Private Bag X01, Brandhof, 9301; E-mail: [email protected] ANDREW SALOMON (South African Heritage Resources Agency - SAHRA) Tel: 021 462 4505; Fax: 021 462 4509; Postal Address: P.O. Box 4637, Cape Town, 8000; E-mail: [email protected] PREPARED BY: KAREN VAN RYNEVELD (ArchaeoMaps) Tel: 084 871 1064; Fax: 086 515 6848; Postal Address: Postnet Suite 239, Private Bag X3, Beacon Bay, 5205; E-mail: [email protected] THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 2 SPECIALIST DECLARATION OF INTEREST I, Karen van Ryneveld (Company – ArchaeoMaps; Qualification – MSc Archaeology), declare that: o I am suitably qualified and accredited to act as independent specialist in this application; o I do not have any financial or personal interest in the application, ’ proponent or any subsidiaries, aside from fair remuneration for specialist services rendered; and o That work conducted has been done in an objective manner – and that any circumstances that may have compromised objectivity have been reported on transparently. SIGNATURE – DATE – 2013-10-17 THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FS ENVIROWORKS 3 PHASE 1 ARCHAEOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT THE LEBONE SOLAR FARM, ONVERWAG RE/728 AND VAALKRANZ 2/220, WELKOM, FREE STATE, SOUTH AFRICA EXECUTIVE SUMMARY TERMS OF REFERENCE - Enviroworks has been appointed by the project proponent, Lebone Solar Farm (Pty) Ltd, to prepare and submit the EIA and EMPr for the proposed 75MW photovoltaic (PV) solar facility on the properties Remaining Extent of Farm Onverwag 728 and Portion 2 of Farm Vaalkranz 220 near Welkom in the Free State, South Africa. -

A Statistical Comparison of the Physical Features of the Zulu

0 A STATISTICAL COr~ARISON OF THE PHYSiCAL FEATURES OF . ~ . THE ZULU-XHOSA AND SOUTH SOTHO-TSWANA PEOPLES OF' SOUTH AFRICA by Frederick Wilhelm Strydom Thesis submitted I'or the degree.of. .DoctorPhil.oso12hiae oi the University of Cape Town; October, 1951 • . I - - The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. ' , '•-.., __ ,. ...... - ... ,._ ...... ' ... , " ..... ~ .- '" ..... .... _ ............... ·- ........ ...... ..... f .. •' 0 The author wishes to express his sincere appre~iation to 'I lY The South African Cotmcil for Scientific and Industrial •. I Research for a sen~cr research grant which made this sur~ . vey possible.· .. 2) The Administrations of Basutoland and the Bechuanaland Pro- . t·ectorate. and t-he· Native CorEmi.ssioners of the· Uniori in the thi~ districts visited, for their. co-.operation whiie.. survey was being carried. ou·t •. 3) Dr. J .A. Keen and .Professor· M.R. Dr·ennan of the Unive·rsi ty · of Cape Town for their very h.elpful guiQ.ance in connection with this :study.· .• 4) Hi;s ·~wife who 3:ccornpanied him to the Nati,ve Reserves, tabu lated ~11 t~e data, did a l.arge part of the calculations, and prepared the album of photographs. ·• p . ' CONTENTS INTRODUCTION. • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Page 4 Mf~ TERIL.L . AND lVIbTHODS. • • • • • . • • • • • •. •. • 5 Ethnic and Historical Background of each Tribe . -

First Phase Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Assessment of the Proposed Borrow Pit Sites Along the R30 Main Road Between Brandfort & Vet River, Free State

28 February 2007 FIRST PHASE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED BORROW PIT SITES ALONG THE R30 MAIN ROAD BETWEEN BRANDFORT & VET RIVER, FREE STATE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Several borrow pits intended for use during the upgrading of the R30 main road between Brandfort and Theunissen, Free State, was investigated. Most of the quarries will be extensions of existing borrow pits and contain no cultural or historical material. Graves occur near two of the sites and should be avoided during excavations. I recommend that the proposed development and planning of the sites may proceed. INTRODUCTION AND DESCRIPTION INVESTIGATION Borrow pits for the upgrading of the R30 main road between Brandfort and Theunissen, were visited on 5 January 2007. Dr Johan du Preez of MDA Environmental Consultants, Bloemfontein, took me to the sites. The area was examined for possible archaeological and historical material and to establish the potential impact on any cultural material that might be found. The Heritage Impact Assessment (HIA) is done in terms of the National Heritage Resources Act (NHRA), (25 of 1999) and under the Environmental Conservation Act, (73 of 1989). 2 LOCALITY Nine borrow pits were investigated along the R30 main road between Brandfort and the Beatrix Mine turn-off near Theunissen, Free State (Map 2). GPS coordinates (Cape scale) are given below: BP km 7,7 at Masjwemasweu, Brandfort. (Map 3). The site contains an existing quarry (Fig.1). 28°40’31”S 026°28’05”E Altitude 1436m. BP km 15,3 Borrow pit on the farm Biesiebult 90 along the R30 main road between Brandfort and Theunissen.