The Deictics of Authenticity in Religious Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Der Tag Im Süden Kreuzfahrt

Der Tag im Süden Der Tag im Süden beinhaltet die Highlights der Insel Mauritius im Süden und Südwesten in einer Tour. Eine vielbesuchte Touristenattraktion ist in Curepipe der Krater Trou aux Cerfs, ein alltägliches Ziel der Jogger von Curepipe. Der Krater Trou aux Cerfs gilt als Monogenetic, das heisst er hatte nur einen Ausbruch bisher. Momentan ist er geologisch schlafend, kann aber in den nächsten 1000 Jahren wieder aktiv werden. Weitere Krater finden sich beim Bassin Blanc, Trou Kanaka und dem Grand Bassin. L`escalier ist mit etwa 20000 Jahren die letzte und damit jüngste Vulkanische Aktivität. Durch seine Höhenlage von etwa 600m bietet der Kamm des Kraterrandes ein herrlichen Blick auf Curepipe sowie das bergige Umland. Wenn das Wetter mitspielt sind hier fast alle Berge von Mauritius in voller Schönheit zu erblicken, ganz in der Nähe Tross Mamelles, Montagne du Rempart und der Corps de Garde. Im Norden sind es der Le Pouce und der Peter Both. Ein kleiner Spaziergang um dem Krater mit seinen etwas mehr als 200m bietet Ihnen einen fantastischen Rundumblick. Grand Bassin Der etwa 2km östlich von Le Pétrin gelegene Kratersee, von den Hindus auch Ganga Talao (See des Ganges) genannt, ist die größte hinduistische Pilgerstätte außerhalb Indiens. Am Eingang von Ganga Talao befindet sich seit 2007 eine 33 m hohe Shiva-Statue. Dies ist die höchste Statue von Mauritius. Bei ihr handelt es sich um eine Kopie der Statue vom Sursagar Talav-See im indischen Vadodara. Auf der anderen Straßenseite befindet sich eine weitere ebenfalls 33 m hohe Statue, die Durga Maa Bhavani zeigt. -

Maha Shivaratri

Maha Shivaratri Maha Shivaratri (Maha Shivratri, Maha Sivaratri, Shivaratri, Sivaratri) is a festival that is dedicated to the worship Lord Shiva on the 13th or 14th day of the Hindu month of Maagha or Phalguna. The festival usually occurs in the month of February or March and is observed for one day and night only. The festival of 'Maha Shivratri' which literally translates to 'the greatest night of Shiva' is one of the most splendidly celebrated festivals across India. But, why is Shivratri celebrated? There is more than one Mahashivaratri story surrounding this occasion. Here are a few: • One is that Lord Shiva married Parvati on this day. So, it is a celebration of this sacred union. • Another is that when the Gods and demons churned the ocean together to obtain ambrosia that lay in its depths, a pot of poison emerged. Lord Shiva consumed this poison, saving both the Gods and mankind. The poison lodged in the Lord’s throat, turning him blue. To honor the savior of the world, Shivratri is celebrated. • One more legend is that as Goddess Ganga descended from heaven in full force, Lord Shiva caught her in his matted locks, and released her on to Earth as several streams. This prevented destruction on Earth. As a tribute to Him, the Shivalinga is bathed on this auspicious night. • Also, it is believed that the formless God Sadashiv appeared in the form of a Lingodhbhav Moorthi at midnight. Hence, people stay awake all night, offering prayers to the God. A student's experience of celebrating Maha Shiviratri I came from Mauritius and Maha Shivaratri is celebrated during the new moon and during this period of time most Hindus will start there pilgrimage to the sacred lake of Ganga Talao located in Grande Bassin. -

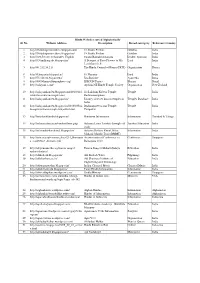

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

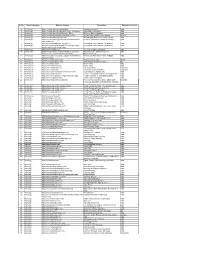

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

PILGRIM CENTRES of INDIA (This Is the Edited Reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the Same Theme Published in February 1974)

VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA A DISTINCTIVE CULTURAL MAGAZINE OF INDIA (A Half-Yearly Publication) Vol.38 No.2, 76th Issue Founder-Editor : MANANEEYA EKNATHJI RANADE Editor : P.PARAMESWARAN PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA (This is the edited reprint of the Vivekananda Kendra Patrika with the same theme published in February 1974) EDITORIAL OFFICE : Vivekananda Kendra Prakashan Trust, 5, Singarachari Street, Triplicane, Chennai - 600 005. The Vivekananda Kendra Patrika is a half- Phone : (044) 28440042 E-mail : [email protected] yearly cultural magazine of Vivekananda Web : www.vkendra.org Kendra Prakashan Trust. It is an official organ SUBSCRIPTION RATES : of Vivekananda Kendra, an all-India service mission with “service to humanity” as its sole Single Copy : Rs.125/- motto. This publication is based on the same Annual : Rs.250/- non-profit spirit, and proceeds from its sales For 3 Years : Rs.600/- are wholly used towards the Kendra’s Life (10 Years) : Rs.2000/- charitable objectives. (Plus Rs.50/- for Outstation Cheques) FOREIGN SUBSCRIPTION: Annual : $60 US DOLLAR Life (10 Years) : $600 US DOLLAR VIVEKANANDA KENDRA PATRIKA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA PILGRIM CENTRES OF INDIA CONTENTS 1. Acknowledgements 1 2. Editorial 3 3. The Temple on the Rock at the Land’s End 6 4. Shore Temple at the Land’s Tip 8 5. Suchindram 11 6. Rameswaram 13 7. The Hill of the Holy Beacon 16 8. Chidambaram Compiled by B.Radhakrishna Rao 19 9. Brihadishwara Temple at Tanjore B.Radhakrishna Rao 21 10. The Sri Aurobindo Ashram at Pondicherry Prof. Manoj Das 24 11. Kaveri 30 12. Madurai-The Temple that Houses the Mother 32 13. -

Maha-Shivaratri Festival Maha Shivaratri

Maha-Shivaratri Festival Maha Shivaratri Maha Shivaratri a Hindu festival celebrated annually in honour of the god Shiva. There is a Shivaratri in every luni-solar month of the Hindu calendar, on the month's 13th night/14th day, but once a year in late winter (February/March, or Magha) and before the arrival of Summer, marks Maha Shivaratri which means "the Great Night of Shiva". It is a major festival in Hinduism, this festival is solemn and marks a remembrance of "overcoming darkness and ignorance" in life and the world. It is observed by remembering Shiva and chanting prayers, fasting, doing Yoga, and meditating on ethics and virtues such as self-restraint, honesty, noninjury to others, forgiveness, and the discovery of Shiva. The ardent devotees keep awake all night. Others visit one of the Shiva temples or go on pilgrimage to Jyotirlingams. This is an ancient Hindu festival whose origin date is unknown. In Kashmir Shaivism, the festival is called Har-ratri or phonetically simpler Haerath or Herath by Shiva faithfuls of the Kashmir region. Description A festival of contemplation During the Vigil Night of Shiva, Mahashivaratri, we are brought to the moment of interval between destruction and regeneration; it symbolizes the night when we must contemplate on that which watches the growth out of the decay. During Mahashivaratri we have to be alone with our sword, the Shiva in us. We have to look behind and before, to see what evil needs eradicating from our heart, what growth of virtue we need to encourage. Shiva is not only outside of us but within us. -

1.Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civilization Indus Valley Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 4 Archaelogy http://www.ancientworlds.net/aw/Post/881715 Ancient Vishnu Idol Found in Russia Russia 5 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/ Archeological Evidence of Vedic System India 6 Archaelogy http://www.archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/scientific- Scientific Verification of Vedic Knowledge India verif-vedas.html 7 Archaelogy http://www.ariseindiaforum.org/?p=457 Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India 8 Archaelogy http://www.dwarkapath.blogspot.com/2010/12/why- Submerged Cities -Ancient City Dwarka India dwarka-submerged-in-water.html 9 Archaelogy http://www.harappa.com/ The Ancient Indus Civilization India 10 Archaelogy http://www.puratattva.in/2010/10/20/mahendravadi- Mahendravadi – Vishnu Temple of India vishnu-temvishnu templeple-of-mahendravarman-34.html of mahendravarman 34.html Mahendravarman 11 Archaelogy http://www.satyameva-jayate.org/2011/10/07/krishna- Krishna and Rath Yatra in Ancient Egypt India rathyatra-egypt/ 12 Archaelogy http://www.vedicempire.com/ Ancient Vedic heritage World 13 Architecture http://www.anishkapoor.com/ Anish Kapoor Architect London UK 14 Architecture http://www.ellora.ind.in/ Ellora Caves India 15 Architecture http://www.elloracaves.org/ Ellora Caves India 16 Architecture http://www.inbalistone.com/ Bali Stone Work Indonesia 17 Architecture http://www.nuarta.com/ The Artist - Nyoman Nuarta Indonesia 18 Architecture http://www.oocities.org/athens/2583/tht31.html Build temples in Agamic way India 19 Architecture http://www.sompuraa.com/ Hitesh H Sompuraa Architects & Sompura Art India 20 Architecture http://www.ssvt.org/about/TempleAchitecture.asp Temple Architect -V. -

MAURITIUS Chamouny Main Dam Baie Du Chemin Or Waterway Cap Grenier Souillac TRAVEL GUIDE MAURITIUS Citrons River

8TH Ed TRAVEL GUIDE LEGEND INDIAN Grand OCEAN Baie Île d’Ambre Area Maps PORT Motorway LOUIS National Road Main Road Trou d’Eau Douce Minor Road Scenic Route Curepipe Track Provincial Mahébourg Boundary MAURITIUS Chamouny Main Dam Baie du Chemin or Waterway Cap Grenier Souillac TRAVEL GUIDE GUIDE TRAVEL Citrons River Waterfall CONTENTS Reef Practical, informative and user-friendly, the 1. Introducing Mauritius Mountain Globetrotter Travel Guide to Mauritius VACOAS MTS The Land Highlands highlights the major places of interest, describing their History in Brief principal attractions and offering sound suggestions Government and Economy Piton Savanne Peak in The People 704 m metres on where to tour, stay, eat, shop and relax. 2. The North Cabinet Nature NR Reserve THE AUTHOR The Northwest Coast PORT Rivière du Rempart Coast City Martine Maurel is a Mauritius-born French graduate, The Northern Offshore Islands LOUIS who spent some years living in Malawi. She has St Felix Town & Village 3. The East Coast and Rodrigues written a number of travel articles and books Place of The Flacq Coast Art Gallery Interest which have been very well received, including Visitor’s Northern Grand Port Coast Airport Mahébourg and Environs Guide to Malawi and Visitor’s Guide to Zimbabwe. Rodrigues Town Plans She has since returned to her native Mauritius, 4. The South and Southwest from where she still writes. Royal Road Main Road Savanne Coastal Belt MAURITIUS Le Morne Peninsula La Paix Other Road MAURITIUS Plaine Champagne Built-up 5. The West Coast Area Petite and Grande Rivière Noire Line Building of Barracks Interest Vital tips for visitors Tamarin Bay to Flic en Flac Published and distributed by Distributed in Africa by Distributed in the USA by South of Port Louis Place of New Holland Publishers (UK) Ltd Map Studio The Globe Pequot Press Worship Best places to stay, eat and shop 6. -

Hindu Websites Sorted Alphabetically Sl

Hindu Websites sorted Alphabetically Sl. No. Website Address Description Broad catergory Reference Country 1 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.com/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 2 http://18shaktipeetasofdevi.blogspot.in/ 18 Shakti Peethas Goddess India 3 http://199.59.148.11/Gurudev_English Swami Ramakrishnanada Leader- Spiritual India 4 http://330milliongods.blogspot.in/ A Bouquet of Rose Flowers to My Lord India Lord Ganesh Ji 5 http://41.212.34.21/ The Hindu Council of Kenya (HCK) Organisation Kenya 6 http://63nayanar.blogspot.in/ 63 Nayanar Lord India 7 http://75.126.84.8/ayurveda/ Jiva Institute Ayurveda India 8 http://8000drumsoftheprophecy.org/ ISKCON Payers Bhajan Brazil 9 http://aalayam.co.nz/ Ayalam NZ Hindu Temple Society Organisation New Zealand 10 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.com/2010/11/s Sri Lakshmi Kubera Temple, Temple India ri-lakshmi-kubera-temple.html Rathinamangalam 11 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/ Journey of lesser known temples in Temples Database India India 12 http://aalayamkanden.blogspot.in/2010/10/bra Brahmapureeswarar Temple, Temple India hmapureeswarar-temple-tirupattur.html Tirupattur 13 http://accidentalhindu.blogspot.in/ Hinduism Information Information Trinidad & Tobago 14 http://acharya.iitm.ac.in/sanskrit/tutor.php Acharya Learn Sanskrit through self Sanskrit Education India study 15 http://acharyakishorekunal.blogspot.in/ Acharya Kishore Kunal, Bihar Information India Mahavir Mandir Trust (BMMT) 16 http://acm.org.sg/resource_docs/214_Ramayan An international Conference on Conference Singapore -

Shiva Lingam to Appease Lord Shiva

Mahashivaratri Festival Mahashivaratri Festival or the ‘The Night of Shiva’ is celebrated with devotion and religious fervor in honor of Lord Shiva, one of the deities of Hindu Trinity. Shivaratri falls on the moonless 14th night of the new moon in the Hindu month of Phalgun, which corresponds to the month of February - March in English Calendar. Celebrating the festival of Shivaratri devotees observe day and night fast and perform ritual worship of Shiva Lingam to appease Lord Shiva. Legends of Mahashivratri There are various interesting legends related to the festival of Maha Shivaratri. According to one of the most popular legends, Shivaratri marks the wedding day of Lord Shiva and Parvati. Some believe that it was on the auspicious night of Shivaratri that Lord Shiva performed the ‘Tandava’, the dance of the primal creation, preservation and destruction. Another popular Shivratri legend stated in Linga Purana states that it was on Shivaratri that Lord Shiva manifested himself in the form of a Linga. Hence the day is considered to be extremely auspicious by Shiva devotees and they celebrate it as Mahashivaratri - the grand night of Shiva. Traditions and Customs of Shivaratri Various traditions and customs related to Shivaratri Festival are dutifully followed by the worshippers of Lord Shiva. Devotees observe strict fast in honor of Shiva, though many go on a diet of fruits and milk some do not consume even a drop of water. Devotees strongly believe that sincere worship of Lord Shiva on the auspicious day of Shivaratri, absolves a person of sins and liberates him from the cycle of birth and death. -

The Survival of Hindu Cremation Myths and Rituals

THE SURVIVAL OF HINDU CREMATION MYTHS AND RITUALS IN 21ST CENTURY PRACTICE: THREE CONTEMPORARY CASE STUDIES by Aditi G. Samarth APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Dr. Thomas Riccio, Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Richard Brettell, Co-Chair ___________________________________________ Dr. Melia Belli-Bose ___________________________________________ Dr. David A. Patterson ___________________________________________ Dr. Mark Rosen Copyright 2018 Aditi G. Samarth All Rights Reserved Dedicated to my parents, Charu and Girish Samarth, my husband, Raj Shimpi, my sons, Rishi Shimpi and Rishabh Shimpi, and my beloved dogs, Chowder, Haiku, Happy, and Maya for their loving support. THE SURVIVAL OF HINDU CREMATION MYTHS AND RITUALS IN 21ST CENTURY PRACTICE: THREE CONTEMPORARY CASE STUDIES by ADITI G. SAMARTH, BFA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2018 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank members of Hindu communities across the globe, and specifically in Bali, Mauritius, and Dallas for sharing their knowledge of rituals and community. My deepest gratitude to Wayan at Villa Puri Ayu in Sanur, Bali, to Dr. Uma Bhowon and Professor Rajen Suntoo at the University of Mauritius, to Pandit Oumashanker, Pandita Barran, and Pandit Dhawdall in Mauritius, to Mr. Paresh Patel and Mr. Ashokbhai Patel at BAPS Temple in Irving, to Pandit Janakbhai Shukla and Pandit Harshvardhan Shukla at the DFW Hindu Ekta Mandir, and to Ms. Stephanie Hughes at Hughes Family Tribute Center in Dallas, for representing their varied communities in this scholarly endeavor, for lending voice to the Hindu community members they interface with in their personal, professional, and social spheres, and for enabling my research and documentation during a vulnerable rite of passage.