Hindu Temples' Digital Journeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tamil Nadu Government Gazette

© [Regd. No. TN/CCN/467/2012-14. GOVERNMENT OF TAMIL NADU [R. Dis. No. 197/2009. 2014 [Price: Rs. 2.40 Paise. TAMIL NADU GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY No. 25A] CHENNAI, WEDNESDAY, JULY 2, 2014 Aani 18, Jaya, Thiruvalluvar Aandu – 2045 Part VI–Section 4 (Supplement) Advertisements by Private Individuals and Private Institutions. PRIESSNITZ INSTITUTE OF NATUROPATHY NAME OF THE NATUROPATHY MEDICAL PRACTITIONERS—2014 2nd LIST 128 Dr. R. Lakshminarayanan (1959) 133 Dr. K. Selvaraj (1903) S/o. Rengasamy, T S/o. K. Kaliannan 1105. Devaji Rao Lane 5/24, Ernapuram West Main Street, Magudanchavadi Post Thanjavur-613 009. Sankagiri Taluk. 129 Dr. V. Marudhachalam (1411) 134 Dr. K. Ramesh (1780) S/o. Velusamy S/o. V. Kumaraswamy Thavathiru Santhalingar B7, Parsn Sesh Nestle Thirumadam, Perur 1st Phase, Twin Bunglow Coimabtore - 641 010. Nanjundapuram Road, Coimbatore - 641 036. 130 Dr. E. Zakir Hussain (1022) S/o. H. Ennayathullah Khan 135 Dr. S.Thulasimani (1928) No. 2, Nehru Nagar D/o. Shanmugam, GST Road, Acharapakkam Post, No. 9. Rathina Sabapathy Road Maduranthakam, T.K. KK Pudur, Saibaba Colony, Kancheepuram Dist-603 301. Coimbatore - 641 038. 131 Dr. Na. Shanmugananthan (1090) 136 Dr. B. Magendiran (1016) S/o. Narayanan, S/o. S. Balaram 16, Pollachi Road, 152, Nethaji Street, Min Nagar, Near Taluk Office Kanchipuram - 631 501. Palladam - 641 664. 137 Dr. K. Shanmugam (1882) 132 Dr. N. Rahupathy (1362) S/o. P. Kaliyappan, S/o. Narayanasamy M.C. Complex, 10/88, Shavara School Bus Stop, 62, Rangammal Kovil Street Maruthamalai Main Road, Pappanaickenpalayam, Kalveerampalayam, Coimbatore - 641 046. Coimbatore - 641 037. -

Gyanvapi Mosque

Gyanvapi Mosque April 10, 2021 In News: The court, headed by judge Ashutosh Tiwari, allowed a civil suit seeking an Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) study of the Gyanvapi Mosque site to determine if it had been “superimposed” after demolishing the Kashi Vishwanath Temple that might have originally stood there. Gyanvapi Mosque Located: Varanasi near Lalita Ghat along the river Ganga,Uttar Pradesh. Emperor: It was constructed by the Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb in 1696. Architecture: The façade is modeled partially on the Taj Mahal’s entrance.The remains of the erstwhile temple can be seen in the foundation, the columns and at the rear part of the mosque History The mosque was built by the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb in 1669 CE, after destroying a Hindu temple. The remnants of the Hindu temple can be seen on the walls of the Gyanvapi mosque. The demolished temple is believed by Hindus to be an earlier restoration of the original Kashi Vishwanath temple. The original temple had been destroyed and rebuilt a number of times. Aurangzeb’s demolition of the temple was also attributed to the escape of the Maratha king Shivaji and the rebellion of local zamindars (landowners). Jai Singh I, the grandson of Raja Man Singh, is alleged to have facilitated Shivaji’s escape from Agra. The temple’s demolition was intended as a warning to the anti-Mughal factions and Hindu religious leaders in the city. Kashi Vishwanath Temple Hindu temples dedicated to Lord Shiva. It is located in Varanasi, Uttar Pradesh. The Temple stands on the western bank of the holy river Ganga, and is one of the twelve Jyotirlingas, or Jyotirlingams, the holiest of Shiva Temples. -

International Day of Yoga Sunday 23Rd June 2019 Time 10Am to 2Pm

International Day of Yoga Sunday 23rd June 2019 Time 10am to 2pm The Archbishop Lanfranc Academy, Mitcham Rd, Croydon CR9 3AS FREE EVENT www.dsym.co.uk • +44 (0)7825 704420 Datta Sahaj Yoga Mission (UK) [email protected] Charity No: 1119454 DSYM UK @DSYMUK DSYM (in Association with local yoga organisations) invites you all to come and join us for the world yoga day to understand yoga and its benefits for humanity at large. Our main guest Swami Sarvasthananda - the Minister-in-Charge at Ramakrishna Vedanta Centre, UK will lead the inauguration of the Yoga day event. To register your attendance, please click: https://dsym.co.uk/international-day-of-yoga-2019-registration/ 21st June was declared as the International Yoga Day by the United Nations General Assembly on 11 December 2014. Yoga, a 5,000-year-old physical, mental and spiritual practice having its origin in India, aims to transform body and mind. The declaration came after the call for the adoption of 21st June as International Yoga Day by Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, during his address to UN General Assembly on 27th September 2014 wherein he stated: “Yoga is an invaluable gift of India’s ancient tradition. It embodies unity of mind and body; thought and action; restraint and fulfilment; harmony between man and nature is a holistic approach to health and well-being. It is not about exercise but to discover the sense of oneness with your- self, the world and the nature. By changing our lifestyle and creating consciousness, it can help us deal with climate change. -

Der Tag Im Süden Kreuzfahrt

Der Tag im Süden Der Tag im Süden beinhaltet die Highlights der Insel Mauritius im Süden und Südwesten in einer Tour. Eine vielbesuchte Touristenattraktion ist in Curepipe der Krater Trou aux Cerfs, ein alltägliches Ziel der Jogger von Curepipe. Der Krater Trou aux Cerfs gilt als Monogenetic, das heisst er hatte nur einen Ausbruch bisher. Momentan ist er geologisch schlafend, kann aber in den nächsten 1000 Jahren wieder aktiv werden. Weitere Krater finden sich beim Bassin Blanc, Trou Kanaka und dem Grand Bassin. L`escalier ist mit etwa 20000 Jahren die letzte und damit jüngste Vulkanische Aktivität. Durch seine Höhenlage von etwa 600m bietet der Kamm des Kraterrandes ein herrlichen Blick auf Curepipe sowie das bergige Umland. Wenn das Wetter mitspielt sind hier fast alle Berge von Mauritius in voller Schönheit zu erblicken, ganz in der Nähe Tross Mamelles, Montagne du Rempart und der Corps de Garde. Im Norden sind es der Le Pouce und der Peter Both. Ein kleiner Spaziergang um dem Krater mit seinen etwas mehr als 200m bietet Ihnen einen fantastischen Rundumblick. Grand Bassin Der etwa 2km östlich von Le Pétrin gelegene Kratersee, von den Hindus auch Ganga Talao (See des Ganges) genannt, ist die größte hinduistische Pilgerstätte außerhalb Indiens. Am Eingang von Ganga Talao befindet sich seit 2007 eine 33 m hohe Shiva-Statue. Dies ist die höchste Statue von Mauritius. Bei ihr handelt es sich um eine Kopie der Statue vom Sursagar Talav-See im indischen Vadodara. Auf der anderen Straßenseite befindet sich eine weitere ebenfalls 33 m hohe Statue, die Durga Maa Bhavani zeigt. -

National Museum Institute

NATIONAL MUSEUM INSTITUTE OF HISTORY OF ART, CONSERVATION AND MUSEOLOGY (Deemed to be University) First Floor, National Museum Campus, Janpath, New Delhi-110011 Website: www.nmi.gov.in, www.nmi.ac.in Email: [email protected] Telephone: 011-23062795, 23062990 Date: 01-10-2020 A Web Repository as a part of project ‘Cultural Heritage of Varanasi: Kashi Vishwanath Temple Corridor’ is required by the Department of History of Art. For this purpose, quotations are invited from professionals for creating a content-based interactive website under the following specifications: i. Dynamic Website ii. No. of Pages will be 200 or more iii. Target users will be scholars, teachers, students, Heritage conservation practitioners, travellers, researcher, architects, art historian etc from the field of art and culture. iv. Main components of the website will include content in the form essays, article, sheets, high resolution images, AV material like videos and recordings, interactive maps, digitised archival content, learning modules etc. v. Specific functionalities of the Website: a. Content Authoring Tool b. Content Management System c. Features Content Section Design d. Visual Engine Design e. Navigation f. Cross- Referencing g. User Interaction with Featured Content h. Search Engine Optimization i. Site Analytics vi. Language for the portal will be in English and Hindi both. vii. The website needs to be completed within four months from the date of the commencement of the contract. Eligibility criteria are as follow: 1. Experience in development of the web repository for more than 5 years; 2. Experience in developing websites for cultural institutions; 3. Experience in designing of the Web Repository; 4. -

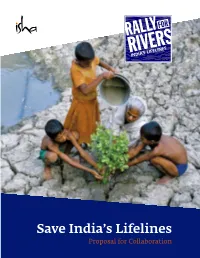

Save India's Lifelines

Save India’s Lifelines Proposal for Collaboration “ Major Indian rivers have depleted dramatically in a matter of a few decades. So far, the approach has been just to exploit the rivers, not rejuvenate them. Water resources and soil are being destroyed at such a rate that in another fifteen to twenty years’ time, we may not be able to feed the 1.3 billion people and quench their thirst anymore. The simplest and most effective solution is to increase the tree coverage around the water bodies. This means we have to work towards creating awareness and induce policy changes.” – Sadhguru, Founder, Isha Foundation The Mahanadi River in Orissa, India, ebbs to a trickle during the dry season. Photo credit: James P. Blair Rally for Rivers Proposal ©Isha FoundationSource: • May 2017http://voices.nationalgeographic.com/2012/03/22/reflections-on-a-thirsty-planet-for-world-water-day/Page 2 Subject Request for partnership for Isha Foundation’s Rally for Rivers. • By joining Sadhguru on one or multiple legs of the rally between September 3rd and October 2nd, 2017 • By endorsing / spreading the word about the cause through social media channel. • Financial sponsorship or any other means. Rally for Rivers Proposal ©Isha Foundation • May 2017 Page 3 Children watch the view of almost dry river Tawi, in Why a Rally for Rivers? Jammu, 17 May 2016. Credit: EPA/Jaipal Singh. Rivers are a lifeline for the human civilization—a vital and accessible water Source: https://thewire. in/41412/droughts-and- source for drinking, irrigation, hygiene and other essential living needs. floods-indias-water-crises- demand-more-than- The current devastation of India’s rivers and water bodies, which support grand-projects/ the livelihood of hundreds of millions of people, is a precursor for the gravest of crises of our times, in a country with a billion-strong population. -

Q & a with Sadhguru

Please click on an article or scroll downwards to read this month’s Sadhguru Speaks: ● Q & A with Sadhguru - Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev in conversation with Kavita Chhibber ● To Be An Emperor Within Yourself - By Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev Q & A With Sadhguru Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev in Conversation with Kavita Chhibber A Kavita Media Presentation. Please email comments here. You can also contact Kavita with your feedback, by dialing 678-720-1260. Selected comments will be broadcast on our webcast Thank you again for the overwhelming response to my continuing conversations with Sadhguru Jaggi Vasudev, the founder of Isha foundation. Sadhguru has requested that everyone who asks a question on this forum to plant 10 trees themselves and if they cannot, please donate the amount to Isha so they can plant the trees in your honor. Kavitachhibber.com is pleased to present questions by those who have shown great generosity and honored Sadhguru’s request. Sadhguru thanks those individuals. Hear his message here. The questions have been reformatted to make better sense. No question is off bounds with Sadhguru and I hope readers will continue to think about life and ask relevant, thought provoking questions so others can also learn from the discussion. Some repetitive or superficial and irrelevant questions have not been answered in this month’s selection. Please do not ask Kriya related questions as they have to be explained. Contact your teachers. Also please do not ask more than 2 questions so others also get an opportunity. Some of the questions have already been answered here and in Mystic’s Musings, and will not be posted again here. -

Maha Shivaratri

Maha Shivaratri Maha Shivaratri (Maha Shivratri, Maha Sivaratri, Shivaratri, Sivaratri) is a festival that is dedicated to the worship Lord Shiva on the 13th or 14th day of the Hindu month of Maagha or Phalguna. The festival usually occurs in the month of February or March and is observed for one day and night only. The festival of 'Maha Shivratri' which literally translates to 'the greatest night of Shiva' is one of the most splendidly celebrated festivals across India. But, why is Shivratri celebrated? There is more than one Mahashivaratri story surrounding this occasion. Here are a few: • One is that Lord Shiva married Parvati on this day. So, it is a celebration of this sacred union. • Another is that when the Gods and demons churned the ocean together to obtain ambrosia that lay in its depths, a pot of poison emerged. Lord Shiva consumed this poison, saving both the Gods and mankind. The poison lodged in the Lord’s throat, turning him blue. To honor the savior of the world, Shivratri is celebrated. • One more legend is that as Goddess Ganga descended from heaven in full force, Lord Shiva caught her in his matted locks, and released her on to Earth as several streams. This prevented destruction on Earth. As a tribute to Him, the Shivalinga is bathed on this auspicious night. • Also, it is believed that the formless God Sadashiv appeared in the form of a Lingodhbhav Moorthi at midnight. Hence, people stay awake all night, offering prayers to the God. A student's experience of celebrating Maha Shiviratri I came from Mauritius and Maha Shivaratri is celebrated during the new moon and during this period of time most Hindus will start there pilgrimage to the sacred lake of Ganga Talao located in Grande Bassin. -

The Deictics of Authenticity in Religious Performance

Mediality and materiality in religious performance: Religion as heritage in Mauritius Patrick Eisenlohr Centre for Modern Indian Studies University of Göttingen [Forthcoming in Material Religion] Abstract: In Mauritius religious performance often doubles as officially recognized diasporic heritage, institutionalized as a component of Mauritians´ “ancestral cultures.” Such forms of religious expression not only point to a source of authority outside Mauritius but also play a key role in legitimizing claims on Mauritian citizenship. In this paper I examine two kinds of practices that help to instantiate religious links as heritage, ritual performance combined with the cultivation of “ancestral language” in the context of a Hindu pilgrimage, and the role of sound reproduction techniques in popularizing a particular genre of Islamic devotional poetry. I argue that these embodied and material practices illustrate two contrasting modes of engaging with spatially and temporally removed sources of authenticity. While the pilgrimage aims at naturalizing diasporic links through their objectification and iconization, uses of sound reproduction technology in Islamic devotional contexts establish links to sources of religious authority under the assumption that the medium used is relatively transparent. Ultimately, the modalities of materiality presupposed in the ethnographic examples account for the authenticating effect of religion as heritage. Key words: Diaspora, Hinduism, Islam, media, ritual, religious authority Frequently, the notions of heritage -

List of Polling Stations for 111 Mettupalayam Assembly Segment

List of Polling Stations for 111 Mettupalayam Assembly Segment within the 19 The Nilgiris Parliamentary Constituency Sl.No Polling station Location and name of building in Polling Areas Whether for All No. which Polling Station located Voters or Men only or Women only 12 3 4 5 1 1 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Nellithurai (R.V) and (P) Nellithurai Ward No. 1 , 2.Nellithurai (R.V) and (P) All Voters School, East Portion North Facing Nandhavanam Pudur B W.No. 1 VI th Std Class Room Nellithurai - 641305 2 2 Sarguru adivasi Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Narayanasamy Pudur W.No. 1 , 2.Odanthurai (R.V) and All Voters School, East Facing southern side (P) Naripallamroad Mampatti W.No.1 , 3.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Ootyroad Gandhi Nagar - 641305 Puliyamarathuroad W.No.1 , 4.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Ootyroad Sunnambukalvai W.No.1 , 5.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Jallimedu Ooty Road W.No.1 , 6.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Railway Station W.No. 2 , 7.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Ooty Road Kallar W.No.2 3 3 Sarguru adivasi Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Pudur W.No. 2 , 2.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) All Voters School, East Facing North side Sachidhanantha Jothi Negethan Valagam W.No. 2 , 3.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Gandhi Nagar - 641305 Kallar Pudur, Railwaygate, Thuripalam W.No.2 , 4.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Naripallam Road Vinobaji Nagar W.No.2 , 5.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Tribal Colony W.No.2 , 6.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Samathuvapuram W.No.2 , 7.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar T.A.S.A Nagar W.No.2 , 8.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Kallar Agasthiyar Nagar W.No.2 4 4 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Omaipalayam Killtheru W.No 3,4 , 2.Odanthurai (R.V) All Voters School, West FacingSouth side and (P) Omaipalayam Meltheru W.No 3,4 RCC building Oomapalayam 641305 5 5 Panchayat Union Elementary 1.Odanthurai (R.V) and (P) Omaipalayam Pudhu Harizana Colony W.No. -

MANDELA Man ‘O’ Man He Refused to Surrender the Human in Him Even to the Most Inhuman No Matter What You Take from Him You Could Not Make Him a Lesser Man

Volume - 2 / Issue - 1 `15 Annual Subscription `180 January 2014 MANDELA Man ‘O’ Man He refused to surrender The human in him even to the most inhuman No matter what you take from him You could not make him a lesser Man Born of bondage and suppression of the worst kind. Unrelenting in his longing for Dignity and Freedom Lived to see demonic rule end Unfettered by bitterness or hate Celebrating freedom with laughter and joy Not many a man were born Like him till our times Hope he spawns many Who will live like him. The future needs many like him Man ‘O’ Man Is rooted the eternal tree. eternal the rooted Is Three times in these is It ofpast the wisdom and the of present the intensity the by awoken is The future Grace & Blessings Editorial Dear Readers, You have been initiated into a yogic kriya or meditation. You sit down and start the practice as instructed. But then, a steady stream of thoughts diverts your attention to all kinds of mundane matters, from snippets of conversations to what to have for dinner. Sounds familiar? Our Lead Article, “Mind Your Garbage” presents Sadhguru’s antidote to frustration in the face of this common challenge. SEKAR. K. In the article “More Than a Man,” Sadhguru describes a new avenue to make spirituality accessible and available to humanity. These new Adiyogi spaces will be monuments to Editor: commemorate the one who first opened up the possibility of raising human consciousness. But not only that – they will also be meditative spaces where anyone, regardless of their religious or cultural backgrounds, can pick a simple spiritual process that can easily be integrated into their lives. -

RASHTRIYA SWAYAMSEVAK SANGH Status of Our Work

RASHTRIYA SWAYAMSEVAK SANGH PRESS NOTE BASED ON REPORT by RSS Sarkaryavah Sri Suresh (Bhaiyya) Joshi during Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha ( ABPS 2018 ) HOMAGE : We feel the pain and vacuum when we experience the absence of close associates, beloved ones, and distinguished personalities from social, political, religious, and cultural fields. In the course of time, many such noble personalities have left us for the final abode. Similarly, many brave- hearts sacrificed their lives in the line of duty for protecting the nation or fighting against the terrorists. It is very painful to accept that many of our brethren fell victim to the violence of political intolerance. Many people have left us due to natural calamities and accidents. The Akhil Bharatiya Pratinidhi Sabha pays homage to all such departed souls and prays for their eternal peace besides expressing deep condolences towards their family members. May the God Almighty give ‘Sadgati’ to the departed souls. Status of our work Sangh Shiksha Varg and Prathmik Shiksha Varg held in 2017-18 Total Sangh Shiksha Varg (SSV): Report on Shakhas: Shakhas in Telangana: Over 1000 shakhas have increased in Telangana over the last 8 years. Currently, 2412 shakhas are running in 1608 places. In 2017, there were 2302 shakhas in 1495 places. Tour of P. P. Sarsanghchalak ji In the year 2017-18, during the tours of P. P. Sarsanghachalak Ji, besides organizational meetings with Karyakartas, interactions with prominent people from various walks of life and special programmes were organized. P.P. Sarsanghachalak ji met President of Ramakrishna Math, Swami Smarananand Ji, Syedana Saheb, a revered figure of Bohra community from Mumbai, Isha Foundation’s Sadguru Jaggi Vasudev Ji, Poojya Bhole ji Maharaj and Poojya Mangala Mata ji of Hans Foundation and Mahamahim Rashtrapati Shri Ramnath Kovind Ji etc.