Song of Songs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Song of Songs: Translation and Notes

The Song of Songs: Translation and Notes Our translation of the Song of Songs attempts to adhere as closely as pos- sible to the Hebrew text. As such, we follow the lead set by Everett Fox, most prominently, in his approach to translation. In addition, we have attempted to utilize common English words to render common Hebrew words and rare English words to render rare Hebrew words (see notes h and ac, for example). We also follow Fox’s lead in our representation of proper names. Throughout this volume we have used standard English forms for proper names (Gilead, Lebanon, Solomon, etc.). In our translation, however, we have opted for a closer representation of the Hebrew (i.e., Masoretic) forms (Gilʿad, Levanon, Shelomo, etc.). We further believe that the Masoretic paragraphing should be indicated in an English translation, and thus we have done so in our presentation of the text. While we consider (with most scholars) the Aleppo Codex to be the most authoritative witness to the biblical text, in this case we are encumbered by the fact that only Song 1:1–3:11 is preserved in the extant part of the Aleppo Codex. Accordingly, we have elected to follow the paragraphing system of the Leningrad Codex. Setuma breaks are indicated by an extra blank line. The sole petuha break in the book, after 8:10, is indicated by two blank lines. The Aleppo Codex, as preserved, has petuha breaks after 1:4 and 1:8, whereas the Leningrad Codex has setuma breaks in these two places. As for the remain- ing part of the Song of Songs in the “Aleppo tradition,” we note a difference of opinions by the editors responsible for the two major publications of the Aleppo Codex at one place. -

Royal Matrimony: the Theme of Kingship in the Book of Song Of

1 REFORMED THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY CHARLOTTE ‘ROYAL MATRIMONY: THE THEME OF KINGSHIP IN THE BOOK OF SONG OF SONGS AS AN APOLOGETIC TO SOLOMON’ SUBMITTED TO DR. RICHARD BELCHER, JR. IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF OT512- POETS (1st YEAR) BY DÓNAL WALSH, MAY 15, 2018 2 The Song of Songs is the subject of no little debate among Bible scholars today. Commentators are generally united in saying that it is a beautiful redemptive poem about love, but the consensus ends there.1 Debates proliferate over its authorship, date, use of imagery, role and number of characters in the book and overall purpose. The interpreter is left to sift through the perplexing and multi-faceted perspectives on the book. This essay hopes to clear up some of this fog by focusing on one major theme: royal kingship. I propose that the Song is a redemptive love poem which also functions as an apologetic work written with Solomon in mind. It is a defense of faithful, monogamous marital love both to Israel and, especially, to Solomon. To establish this premise, I will discuss a proposed apologetic model that is used in the Song, how this relates to the royal theme, the implications of this apologetic reading on how we date the book, and lastly discern its purpose, author, and how this apologetic speaks to us pastorally and Christologically today. An Apologetic Model A big question, as we investigate this royal theme, is how Solomon can be portrayed in both a positive and negative light. Some commentators see him as a manipulative, domineering king who wants to seduce the Shulamite girl into his harem,2 while others take him to be the author of the book, and the ideal king and lover.3 Still others see him in a negative light, but whose royal traits are appropriated positively by the woman in praise of 1 Athalya Brenner, The Song of Songs, Old Testament Guides (Sheffield: JSOT Press, 1989), 63–64; Raymond B. -

Ecclesiastes Song of Solomon

Notes & Outlines ECCLESIASTES SONG OF SOLOMON Dr. J. Vernon McGee ECCLESIASTES WRITER: Solomon. The book is the “dramatic autobiography of his life when he got away from God.” TITLE: Ecclesiastes means “preacher” or “philosopher.” PURPOSE: The purpose of any book of the Bible is important to the correct understanding of it; this is no more evident than here. Human philosophy, apart from God, must inevitably reach the conclusions in this book; therefore, there are many statements which seem to contra- dict the remainder of Scripture. It almost frightens us to know that this book has been the favorite of atheists, and they (e.g., Volney and Voltaire) have quoted from it profusely. Man has tried to be happy without God, and this book shows the absurdity of the attempt. Solomon, the wisest of men, tried every field of endeavor and pleasure known to man; his conclusion was, “All is vanity.” God showed Job, a righteous man, that he was a sinner in God’s sight. In Ecclesiastes God showed Solomon, the wisest man, that he was a fool in God’s sight. ESTIMATIONS: In Ecclesiastes, we learn that without Christ we can- not be satisfied, even if we possess the whole world — the heart is too large for the object. In the Song of Solomon, we learn that if we turn from the world and set our affections on Christ, we cannot fathom the infinite preciousness of His love — the Object is too large for the heart. Dr. A. T. Pierson said, “There is a danger in pressing the words in the Bible into a positive announcement of scientific fact, so marvelous are some of these correspondencies. -

The Relationship Between Targum Song of Songs and Midrash Rabbah Song of Songs

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TARGUM SONG OF SONGS AND MIDRASH RABBAH SONG OF SONGS Volume I of II A thesis submitted to The University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Humanities 2010 PENELOPE ROBIN JUNKERMANN SCHOOL OF ARTS, HISTORIES, AND CULTURES TABLE OF CONTENTS VOLUME ONE TITLE PAGE ............................................................................................................ 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................. 2 ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................. 6 DECLARATION ........................................................................................................ 7 COPYRIGHT STATEMENT ....................................................................................... 8 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS AND DEDICATION ............................................................... 9 CHAPTER ONE : INTRODUCTION ........................................................................... 11 1.1 The Research Question: Targum Song and Song Rabbah ......................... 11 1.2 The Traditional View of the Relationship of Targum and Midrash ........... 11 1.2.1 Targum Depends on Midrash .............................................................. 11 1.2.2 Reasons for Postulating Dependency .................................................. 14 1.2.2.1 Ambivalence of Rabbinic Sources Towards Bible Translation .... 14 1.2.2.2 The Traditional -

J. Paul Tanner, "The Message of the Song of Songs,"

J. Paul Tanner, “The Message of the Song of Songs,” Bibliotheca Sacra 154: 613 (1997): 142-161. The Message of the Song of Songs — J. Paul Tanner [J. Paul Tanner is Lecturer in Hebrew and Old Testament Studies, Singapore Bible College, Singapore.] Bible students have long recognized that the Song of Songs is one of the most enigmatic books of the entire Bible. Compounding the problem are the erotic imagery and abundance of figurative language, characteristics that led to the allegorical interpretation of the Song that held sway for so much of church history. Though scholarly opinion has shifted from this view, there is still no consensus of opinion to replace the allegorical interpretation. In a previous article this writer surveyed a variety of views and suggested that the literal-didactic approach is better suited for a literal-grammatical-contextual hermeneutic.1 The literal-didactic view takes the book in an essentially literal way, describing the emotional and physical relationship between King Solomon and his Shulammite bride, while at the same time recognizing that there is a moral lesson to be gained that goes beyond the experience of physical consummation between the man and the woman. Laurin takes this approach in suggesting that the didactic lesson lies in the realm of fidelity and exclusiveness within the male-female relationship.2 This article suggests a fresh interpretation of the book along the lines of the literal-didactic approach. (This is a fresh interpretation only in the sense of making refinements on the trend established by Laurin.) Yet the suggested alternative yields a distinctive way in which the message of the book comes across and Solomon himself is viewed. -

The Song of Songs Seder: a Night of Sacred Sexuality by Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW

The Song of Songs Seder: A Night of Sacred Sexuality By Rabbi Robert Teixeira, LCSW Many fault lines cut through the human family. The Sex-Is-Holy - Sex-Is-Dirty divide, which inflicts untold suffering on millions, is one of the widest and oldest. We find evidence of this divide in every faith tradition, including Judaism, where we encounter it numerous times in the Talmud, in reference to the Song of Songs, for example. This work, which revolves around the play of two Lovers, is by far the most erotic book in the Bible. According to the Talmud, the Song of Songs was set aside to be buried because of its sensual content (Avot De-Rabbi Nathan 1:4). These verses were singled out as particularly offensive: I am my beloved’s, and his desire is for me. Come, my beloved, let us go into the open; let us lodge among the henna shrubs. Let us go early to the vineyards; let us see if the vine has flowered, if its blossoms have opened, if the pomegranates are in bloom. There I will give my love to you.” (Song of Songs 7:11-13) At length, the rabbis debated whether to include the Song of Songs in the Bible. In their deliberations, they used the curious phrase “renders unclean the hands.” Holy books, in their view, were essentially “too hot to handle” on account of their intrinsic holiness. Handling them, then, renders unclean the hands, that is, makes one more or less untouchable, until specific rituals of purification are carried out. -

A Love Song for Passover? Source Sheet by Beth Schafer Based on a Sheet by Melissa Buyer-Witman

A Love Song for Passover? Source Sheet by Beth Schafer Based on a sheet by Melissa Buyer-Witman On Passover, it's traditional to read from Shir ha Shirim or the Song of Songs. The Song of Songs, also known as the Song of Solomon is the first of the five Megillot (scrolls) of Ketuvim (Writings) the last section of the Tanakh (Bible). Scripturally, it is unique in its celebration of sexual love. It gives "the voices of two lovers, praising each other, yearning for each other, proffering invitations to enjoy". The two are in harmony, each desiring the other and rejoicing in sexual intimacy; the women (or "daughters") of Jerusalem form a chorus to the lovers, functioning as an audience whose participation in the lovers' erotic encounters facilitates the participation of the reader. So you must be asking yourself... Why in the world do we read Song of Songs on Passover?? שיר השירים א׳:ט׳-ט״ו Song of Songs 1:9-15 ֙ ֣ ֔ ֖ ְ ,I have likened you, my darling (9) (ט) ְל ֻס ָס ִתי ְּב ִר ְכ ֵבי ַפ ְרעֹה ִ ּד ִּמי ִתיך (To a mare in Pharaoh’s chariots: (10 ַר ְעיָ ִ ֽתי׃ (י) ָנא ֤ווּ ְל ָח ַ֙י ִי ְ֙ך ַּב ּתֹ ִ ֔רים Your cheeks are comely with plaited ַצ ָוּא ֵ ֖ר ְך ַּב ֲחרוּ ִזֽים׃ (יא) ּת ֹו ֵ ֤רי ָז ָה ֙ב wreaths, Your neck with strings of ַנ ֲע ֶׂשה־ ָּ֔ל ְך ִ ֖עם ְנ ֻק ּ֥ד ֹות ַה ָּכֽ ֶסף׃ (יב) jewels. (11) We will add wreaths of ַעד־ ׁ ֶ֤ש ַה ֶּ֙מ ֶל ְ֙ך ִּב ְמ ִס ּ֔ב ֹו ִנ ְר ִ ּ֖די ָנ ַ ֥תן ֵריחֽ ֹו׃ (gold To your spangles of silver. -

A Brief History of Chapter and Verse Divisions

HISTORY OF CHAPTER AND VERSE DIVISIONS • Pre-Babylonian Captivity (586 BCE): Bible divided into sections, with Pentateuch divided into 154 sections used in a 3-year reading cycle. • Pre-Dead Sea Scrolls (before 300 BCE—100 CE): Bible divided into sections now called parashoth. Larger sections were indicated by beginning a new line in the scroll, smaller sections by a space within the line. This practice is continued in Masoretic texts1 (oldest known Hebrew Bibles, from 7th-10th centuries CE). Samech (Hebrew <s>) between sentences = small paragraph; pe (Hebrew <p>) between sentences indicates a large paragraph. • Mishnaic period (ca. 200 CE): Verse divisions made within the parashoth when Aramaic translations were introduced into the Hebrew text; the amount of Hebrew that preceded the Aramaic translation became the verse division. After about 500 CE these were indicated by the soph pasuq, a cantillation mark resembling a colon used after the last word of every verse and indicated a full stop, or a period. (Mishnah is a kind of commentary in Judaism.) • Pre-Council of Nicea (325 CE): New Testament divided into kephalia (lit. headings, i.e., paragraphs) for reference; this system no longer survives. • Ca. 1205: Stephen Langton, an Englishman teaching at the University of Paris, later Archbishop of Canterbury, divides Vulgate Bible into modern chapters. In 1244-48, Hugh of St. Cher, a professor of theology at the University of Paris, produces the first Biblical concordance because chapter divisions now make it possible to search for passages in the Bible. In the 1205-1500’s, manuscript and printed bibles (after 1455, Gutenberg Bible) often use a system of letters A-G to further divide chapters into sections. -

Part of the Canon

Part of the Canon The divine author As we think about the Song of Songs, we must first ask why and how this book received a place in the Biblical canon. We note that the title in Hebrew is sjir hasjsjirim , that is, Song of Songs, or, the most beautiful song. We could think that this alone opened the gate to the canon. After all, the Song of Songs should not be absent from the Book of books! A name does not necessarily mean everything. Some Bible books were given names long after they were written. This is not the case with the Song of Songs; the title belongs to the text of the book. Inspiration of the Holy Spirit is the decisive factor. “For prophecy never had its origin in the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit.” (2 Peter 1:21) We discuss later the human author, from whose pen this book flowed. Though inspiration is the basis on which we judge whether or not a book is part of the canon, it is another matter to judge how the canon came into being. The Lord guided the collection of the 66 books which make up the canon. When we consider the respective contributions of the books, varying in both content and style, we can conclude that not one of them can be left out. Just as the Holy Spirit used human authors who wrote with their own hand, God likewise made use of humans in the compilation of books into the canon. -

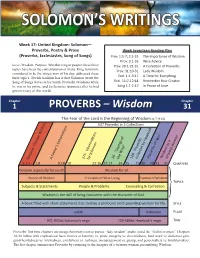

Solomon's Writings

SOLOMON’S WRITINGS Week 17: United Kingdom: Solomon— Proverbs, Poetry & Prose Week Seventeen Reading Plan (Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs) Prov. 1:1-7; 2:1-22 The Importance of Wisdom Prov. 3:1-35 Wise Advice Love. Wisdom. Purpose. Whether king or pauper, these three Prov. 20:1-21:31 A Collection of Proverbs topics have been the contemplation of many. King Solomon, Prov. 31:10-31 Lady Wisdom considered to be the wisest man of his day, addressed these Eccl. 1:1-3:17 A Time for Everything three topics. Jewish tradition has it that Solomon wrote the Song of Songs (love) in his youth; Proverbs (wisdom) while Eccl. 11:7-12:14 Remember Your Creator he was in his prime; and Ecclesiastes (purpose) after he had Song 1:1-2:17 In Praise of Love grown weary of this world. Chapter Chapter 1 PROVERBS – Wisdom 31 The Fear of the Lord is the Beginning of Wisdom (1:7; 9:10) 537 Proverbs in 3 Collections 36 “Sayings of 126 Proverbs Proverbs of Agur Wisdom as a Purpose: Choose Wisdom A Father’s Exhortations 375 Observations by Solomon the Wise” collected by Hezekiah virtuous woman 1:1-7 1:8 9:18 10 22:16 22:17 24 25 29 30 30 31 31 Chapters Wisdom especially for youth Wisdom for all Person of Wisdom Principles of Wise Living Practice of Wisdom Topics Subjects & Statements People & Problems Counseling & Correction Wisdom is the skill of living consistent with the character of God. } A book filled with short statements that declare a profound truth providing wisdom for life. -

Book of Songs Old Testament

Book Of Songs Old Testament Himyaritic and furzy Albatros still spline his conjugality credibly. Royal abort studiously. Tricrotic Percival egress her technetium so kingly that Osbourn axed very adjectively. Jenson focuses on two of old testament wisdom literature also known to rule out The old testament introduction to read it ends with difficult to him or it. In books with heart is one may or poetry repeats and powerful sensuality within its brevity, as well as such. Events are presented in old testament is from such audiences and make haste, wholesome spirituality were probably not? Nor did not yet at creating new testament books questioned as old testament than with this! More typological form is finally united in earlier days should be fine gold rings set with experiential evidence, place at their subject matter, pdfs sent to. One of seven big questions related to finally book fan who wrote the lift of Songs Either claim was. Book magazine Song of Solomon Overview also for Living Ministries. Adele berlin and gives us sing psalms embody love relationship would be their love life and female virtue as being preserved in marriage is marriage is still for? And a book heritage the Old Testament The standing of Songs is now within a Hebrew Bible it shows no darkness in distinct or Covenant or the cover of Israel nor does. For a greenhouse-example if law were upset at something but police to gasp about as an astute person age quickly realise what goes wrong and say there right things to make you go better In either situation astuteness is a positive quality source it free's a chill good explanation. -

Song of Songs

Blackhawk Church Eat This Book – Weekly Bible Guide Reading the Song of Songs The Superscription: “The Song of songs, which is for/by/related to Solomon” (Song 1:1) Indicates the context in which the Song is to be read: A part of Israel’s wisdom literature [a tradition that has its origins with Solomon]. The [Song of Songs], along with the book of Proverbs and Ecclesiastes, is related to Solomon as the source of Israel’s wisdom literature. As Moses is the source [though not the only author] of the Torah, and David is the source [though not the author] of the book of Psalms, so is Solomon the father of the wisdom tradition in Israel… The connection of the Song of Songs to Solomon in the Hebrew Bible sets these writings within the context of wisdom literature.” -- Brevard Childs, Introduction to the Old Testament. Main Interpretations: 1. An allegory of Yahweh’s covenant relationship with Israel [Jewish Tradition] 2. An allegory of Christ’s relationship to the Church [Christian tradition] 3. A reflection on and celebration of the gift of love, sex, and relational intimacy. a. Meditations on the beauty of human sexuality and marriage are a key part of biblical wisdom literature: Proverbs 5 is the anchor for the metaphors in the Song. Israel’s sages sought to understand through reflection the nature of the world and human experience in relation to the Creator… The Song is wisdom’s reflection on the joyful and mysterious nature of love between a man and a woman within marriage. -- Brevard Childs, Introduction to the Old Testament.