Microcomputers in Development: a Manager's Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North Star MDS Micro Disk System Double Density

NorthSbrCompumlnc 2547 Ninth Street Berkeley, Co. 94710 MICRO-DISK SYSTEM MDS-A-D DOUBLE DENSITY Table of Contents Introduction. ..... • 2 Cautions ...... 2 Limited Hardware Warranty 3 Out of Warranty Repair .. 3 Limited Software Warranty 4 Software License ...•. 4 Parts List ........ 5 Assembly Information ••. 8 ,< Figure lA: Identification of Components 10 Assembly and Check-out Instructions 11 l System Integration .•••.... 22 , Theory of Operation ••••• 27 ! Appendix 1: Pulse Signal Detection 35 I Schematic Drawings ••.•••.• 36 -~ I ; Copyright 1978, North star Computers, Inc. MDS-D REVISION 2 25010 INTRODUCTION The North Star Micro-Disk System (MDS-A-O) is a complete floppy disk system for use with 5-100 bus computers. The system .• includes the disk controller board, one floppy disk drive, power regulation, cables, software and documentation. The software is provided on diskette and includes the North Star Disk Operating System, BASIC Language System, Monitor, and various utility programs. The system is capable of controlling up to four disk drives. Each disk drive can record 179,200 bytes of information on a diskette, thus allowing up to 716,800 bytes of on-line disk storage. Addition disk drives, AC power supplies, and cabinets are available as options If you have purchased the MDS-A-D as a kit, then first skim the entire manual. Be sure to carefully read the Assembly Information section before beginning assembly. If you have purchased the MDS-A-D in assembled form, you may skip the A Assembly section. ., CAUTIONS .- 1. Correct this document from the errata before doing anything else. 2. Do NOT insert or remove the MDS controller from the computer while the power is turned on. -

Considerations for Use of Microcomputers in Developing Countrystatistical Offices

Considerations for Use of Microcomputers in Developing CountryStatistical Offices Final Report Prepared by International Statistical Programs Center Bureau of the Census U.S. Department of Commerce Funded by Office of the Science Advisor (c Agency for International Development issued October 1983 IV U.S. Department of Commerce Malcolm Baldrige, Secretary Clarence J. Brown, Deputy Secretary BUREAU OF THE CENSUS C.L. Kincannon, Deputy Director ACKNOWLEDGE ME NT S This study was conducted by the International Statistical Programs Center (ISPC) of the U.S. Bureau of the Census under Participating Agency Services Agreement (PASA) #STB 5543-P-CA-1100-O0, "Strengthening Scientific and Technological Capacity: Low Cost Microcomputer Technology," with the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID). Funding fcr this project was provided as a research grant from the Office of the Science Advisor of AID. The views and opinions expressed in this report, however, are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect those of the sponsor. Project implementation was performed under general management of Robert 0. Bartram, Assistant Director for International Programs, and Karl K. Kindel, Chief ISPC. Winston Toby Riley III provided input as an independent consultant. Study activities and report preparation were accomplished by: Robert R. Bair -- Principal Investigator Barbara N. Diskin -- Project Leader/Principal Author Lawrence I. Iskow -- Author William K. Stuart -- Author Rodney E. Butler -- Clerical Assistant Jerry W. Richards -- Clerical Assistant ISPC would like to acknowledge the many microcomputer vendors, software developers, users, the United Nations Statistical Office, and AID staff and contractors that contributed to the knowledge and experiences of the study team. -

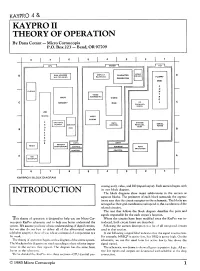

KAYPRO II THEORY of OPERATION by Dana Cotant Micro Cornucopia P.O

KAYPRO 4 & KAYPRO II THEORY OF OPERATION By Dana Cotant Micro Cornucopia P.O. Box 223 — Bend, OR 97709 CPU VIDEO VIDEO RAM ADDRESS DISPLAY CHARACTER DRIVER MULTIPLEXING BLANKING FLOPPY GENERATION DISK C 0 CLOCKS N VIDEO T ADDRESSING R MAIN VIDEO 0 OP L MEMORY RAM PARALLEL PORTS VIDEO CLOCKS DATA SYSTEM SERIAL CONTROL PARALLEL PORTS PORT DATA ADDRESS PORT SE LECTION CONTROL KAYPRO II BLOCK DIAGRAM cessing unit), video, and 1/0 (input/output). Each section begins with its own block diagram. INTRODUCTION The block diagrams show major subdivisions in the section as separate blocks. The perimeter of each block surrounds the approx- imate area that the circuit occupies on the schematic. The blocks are arranged so their grid coordinates correspond to the coordinates of the related circuitry. The text that follows the block diagram describes the parts and signals responsible for the each circuit's function. This theory of operation is designed to help you use Micro Cor- Where the circuits have been modified since the KayPro was in- nucopia's KayPro schematic and to help you better understand the troduced, both circuit forms are described. system. We assume you have a basic understanding of digital circuits, Following the section description is a list of all integrated circuits but we also do our best to define all of the abbreviated symbols used in that section. (alphabet soup) for those of you whose command of computerese is a A star following a signal label indicates that the signal is active low. bit weak. For example, MREQ* is active low, hut DRQ is active high. -

Classification of Computers

Chapter-2 Classification of Computers Computers can be classified many different ways -- by size, by function, or by processing capacity. Functionality wise 4 types a) Micro computer b) Mini Computer c) Mainframe Computer d) Super Computer Microcomputers Microcomputers are connected to networks of other computers. The price of a microcomputer varies from each other depending on the capacity and features of the computer. Microcomputers make up the vast majority of computers. Single user can interact with this computer at a time. It is a small and general purpose computer. Mini Computer Mini Computer is a small and general purpose computer. It is more expensive than a micro computer. It has more storage capacity and speed. It designed to simultaneously handle the needs of multiple users. Mainframe Computer Large computers are called Mainframes. Mainframe computers process data at very high rates of speed, measured in the millions of instructions per second. They are very expensive than micro computer and mini computer. Mainframes are designed for multiple users and process vast amounts of data quickly. Examples: - Banks, insurance companies, manufacturers, mail-order companies, and airlines are typical users. Super Computers The largest computers are Super Computers. They are the most powerful, the most expensive, and the fastest. They are capable of processing trillions of instructions per second. It uses governmental agencies, such as:- Chemical analysis in laboratory Space exploration National Defense Agency National Weather Service Bio-Medical research Design of many other machines Limitations of Computer Computer cannot take over all activities simply because they are less flexible than humans. It does not hold intelligence of its own. -

Inside the Computer Microcomputer Minicomputer Mainframe

Inside the computer Microcomputer Classification of Systems: • Personal Computer / Workstation. – Microcomputer • Desktop machine, including portables. – Minicomputer • Used for small, individual tasks - such as – Mainframe simple desktop publishing, small business – Supercomputer accounting, etc.... • Typical cost : £500 to £5000. • Chapters 1-5 in Capron • Example : The PCs in the labs are microcomputers. Minicomputer Mainframe • Medium sized server • Large server / Large Business applications • Desk to fridge sized machine. • Large machines in purpose built rooms. • Used for distributed data processing and • Used as large servers and for intensive multi-user server support. business applications. • Typical cost : £5,000 to £500,000. • Typical cost : £500,000 to £10,000,000. • Example : Scarlet is a minicomputer. • Example : IBM ES/9000, IBM 370, IBM 390. Supercomputer • Scientific applications • Large machines. • Typically employ parallel architecture (multiple processors running together). • Used for VERY numerically intensive jobs. • Typical cost : £5,000,000 to £25,000,000. • Example : Cray supercomputer 1 What's in a Computer System? Software • The Onion Model - layers. • Divided into two main areas • Hardware • Operating system • BIOS • Used to control the hardware and to provide an interface between the user and the hardware. • Software • Manages resources in the machine, like • Where does the operating system come in? • Memory • Disk drives • Applications • includes games, word-processors, databases, etc.... Interfaces Hardware • The chunky stuff! •CUI • If you can touch it... it's probably hardware! • Command Line Interface • The mother board. •GUI • If we have motherboards... surely there must be • Graphical User Interface fatherboards? right? •WIMP • What about sonboards, or daughterboards?! • Windows, Icons, Mouse, Pulldown menus • Hard disk drives • Monitors • Keyboards BIOS Basics • Basic Input Output System • Directly controls hardware devices like UARTS (Universal Asynchronous Receiver-Transmitter) - Used in COM ports. -

CPU, Microcomputer and Microcontroller

Chapter 1 Types, Selection, and Applications of Microcontrollers Lesson 2 CPU, Microcomputer and Microcontroller 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 2 CPU Program-flow control Section Fetch Unit Control unit Internal Buses Instruction Execution Section Arithmetic +,-,, Rotate and Logic XOR, OR, Unit Shift AND,NOT 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 3 Internal bus Fetch IR Decode ID Control Execution and Sequencer Circuits CPU 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 4 CPU and Buses Fetch Unit Memory IO Devices Control unitProgram Counter Arithmetic and Logic Control Data Unit Bus Bus Address Bus 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 5 Microprocessor - Chip or VLSI Section Cache Reset CPU circuit Registers Clock circuit Stack 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 6 Microcomputer Chip or VLSI Core Microprocessor Memory Interrupt Timing Unit Handler unit IO Devices Data Control Bus Bus Address Bus 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 7 Computer System Microprocessor Micro- Ports Memory computer CD Interrupt Handler unit drive Timing Unit Hard Disk Keyboard Peripherals 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 8 Microcontroller Chip or VLSI Core CPU Micro- Ports Memory computer Interrupt Handler unit Serial Devices Timing Devices Watchdog Timer Application specific Devices PWM ADC 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 9 Embedded processor - Chip or VLSI Core Cache Reset CPU circuit Large register sets Clock Fast context switching circuit Registers based ALU 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 10 Embedded Microcontroller 2011 Microcontrollers-... 2nd Ed. Raj Kamal Pearson Education 11 Embedded Microcontroller CPU Micro- Ports Memory computer Interrupt Handler unit Serial Devices Timing Devices Application Watchdog Timer specific Devices PWM ADC No external memory or devices based system 2011 Microcontrollers-.. -

Microcomputers: NQS PUBLICATIONS Introduction to Features and Uses

of Commerce Computer Science National Bureau and Technology of Standards NBS Special Publication 500-110 Microcomputers: NQS PUBLICATIONS Introduction to Features and Uses QO IGf) .U57 500-110 NATIONAL BUREAU OF STANDARDS The National Bureau of Standards' was established by an act ot Congress on March 3, 1901. The Bureau's overall goal is to strengthen and advance the Nation's science and technology and facilitate their effective application for public benefit. To this end, the Bureau conducts research and provides; (1) a basis for the Nation's physical measurement system, (2) scientific and technological services for industry and government, (3) a technical basis for equity in trade, and (4) technical services to promote public safety. The Bureau's technical work is per- formed by the National Measurement Laboratory, the National Engineering Laboratory, and the Institute for Computer Sciences and Technology. THE NATIONAL MEASUREMENT LABORATORY provides the national system of physical and chemical and materials measurement; coordinates the system with measurement systems of other nations and furnishes essential services leading to accurate and uniform physical and chemical measurement throughout the Nation's scientific community, industry, and commerce; conducts materials research leading to improved methods of measurement, standards, and data on the properties of materials needed by industry, commerce, educational institutions, and Government; provides advisory and research services to other Government agencies; develops, produces, and -

North Star Micro-Disk System MDS-A-D Manual

NorthStarComputersInc. 2547 Ninth Street Berkeley, Ca. 94710 MICRO-DISK SYSTEM MDS-A-D DOUBLE DENSITY Table of Contents Introduction . 2 Cautions . 2 Limited Hardware Warranty . 3 Out of Warranty Repair . 3 Limited Software Warranty . 4 Software License . 4 Parts List . 5 Assembly information . 8 Figure IA: Identification of Components . 10 Assembly and Check-out Instructions . 11 System Integration . 22 Theory of Operation . 27 Appendix 1: Pulse Signal Detection . 35 Schematic Drawings . 36 Copyright 1978, North Star Computers, Inc. MDS-D REVISION 1 INTRODUCTION The North Star Micro-Disk System (MDS-A-D) is a complete floppy disk system for use with S-100 bus computers. The system includes the disk controller board, one floppy disk drive, power regulation, cables, software and documentation. The software is provided on diskette and includes the North Star Disk Operating System, BASIC Language System, Monitor, and various utility programs. The system is capable of controlling up to four disk drives. Each disk drive can record 179,200 bytes of information on a diskette, thus allowing up to 716,800 bytes of on-line disk storage. Addition disk drives, AC power supplies, and cabinets are available as options If you have purchased the MDS-A-D as a kit, then first skim the entire manual. Be sure to carefully read the Assembly Information section before beginning assembly. If you have purchased the MDS-A-D in assembled form, you may skip the Assembly section. CAUTIONS 1. Correct this document from the errata before doing anything else. 2. Do NOT insert or remove the MDS controller from the computer while the power is turned on. -

CP/M-80 Kaypro

$3.00 June-July 1985 . No. 24 TABLE OF CONTENTS C'ing Into Turbo Pascal ....................................... 4 Soldering: The First Steps. .. 36 Eight Inch Drives On The Kaypro .............................. 38 Kaypro BIOS Patch. .. 40 Alternative Power Supply For The Kaypro . .. 42 48 Lines On A BBI ........ .. 44 Adding An 8" SSSD Drive To A Morrow MD-2 ................... 50 Review: The Ztime-I .......................................... 55 BDOS Vectors (Mucking Around Inside CP1M) ................. 62 The Pascal Runoff 77 Regular Features The S-100 Bus 9 Technical Tips ........... 70 In The Public Domain... .. 13 Culture Corner. .. 76 C'ing Clearly ............ 16 The Xerox 820 Column ... 19 The Slicer Column ........ 24 Future Tense The KayproColumn ..... 33 Tidbits. .. .. 79 Pascal Procedures ........ 57 68000 Vrs. 80X86 .. ... 83 FORTH words 61 MSX In The USA . .. 84 On Your Own ........... 68 The Last Page ............ 88 NEW LOWER PRICES! NOW IN "UNKIT"* FORM TOO! "BIG BOARD II" 4 MHz Z80·A SINGLE BOARD COMPUTER WITH "SASI" HARD·DISK INTERFACE $795 ASSEMBLED & TESTED $545 "UNKIT"* $245 PC BOARD WITH 16 PARTS Jim Ferguson, the designer of the "Big Board" distributed by Digital SIZE: 8.75" X 15.5" Research Computers, has produced a stunning new computer that POWER: +5V @ 3A, +-12V @ 0.1A Cal-Tex Computers has been shipping for a year. Called "Big Board II", it has the following features: • "SASI" Interface for Winchester Disks Our "Big Board II" implements the Host portion of the "Shugart Associates Systems • 4 MHz Z80-A CPU and Peripheral Chips Interface." Adding a Winchester disk drive is no harder than attaching a floppy-disk The new Ferguson computer runs at 4 MHz. -

KAYPRO 10 User's Guide, Copying Fi Les from One User Area to Another, for the Prodedure

I - ~------- - - - • - --- - -- --~ - - - - ~ -- - - - --- ---_---.. ---------- --- ---------- o o o ,.' . ''', ',. THE ---- -- -- -------- - -- -- ---- - ------- . ----- ------ -- - =-- -- ------ ---_... -------- - - ~ USER'S GUDE ., . © January 1984 Part Number 1409 E.O.81-176-18-F COPYRIGHT AND TRADEMARK © 1983 Kaypro Corporation. KAYPRO 10 is a registered trademark of Kaypro Corporation. DISCLAIMER Kaypro Corporation hereby disclaims any and all liability resulting from the failure of other manufacturers' software to be operative within and upon the KAYPRO 10 computer, due to Kaypro's inability to have tested each entry of software. LIMITED WARRANTY Kaypro Corporation warrants each new instrument or computer against defects in material or workmanship for a period of ninety days from date of delivery to the original customer. Fuses are excluded from this warranty. This warranty is specifically limited to the replacement or repair of any such defects, without charge, when the complete instrument is returned to one of our authorized dealers or Kaypro Corporation, 533 Stevens Avenue, Solana Beach, California 92075, transportation charges prepaid. This express warranty excludes all other warranties, express or implied, in cluding, but not limited to, implied warranties of merchantability, and fitness for purpose, and KAYPRO CORPORATION IS NOT LIABLE FOR A BREACH OF WARRANTY IN AN AMOUNT EXCEEDING THE PURCHASE PRICE OF THE GOODS. KAYPRO CORPORATION SHALL NOT BE LIABLE FOR INCIDENTAL OR CONSEQUENTIAL DAMAGES. No liability is assumed for -

First Osborne Group (FOG) Records

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8611668 No online items First Osborne Group (FOG) records Finding aid prepared by Jack Doran and Sara Chabino Lott Processing of this collection was made possible through generous funding from the National Archives’ National Historical Publications & Records Commission: Access to Historical Records grant. Computer History Museum 1401 N. Shoreline Blvd. Mountain View, CA, 94043 (650) 810-1010 [email protected] August, 2019 First Osborne Group (FOG) X4071.2007 1 records Title: First Osborne Group (FOG) records Identifier/Call Number: X4071.2007 Contributing Institution: Computer History Museum Language of Material: English Physical Description: 26.57 Linear feet, 3 record cartons, 5 manuscript boxes, 2 periodical boxes, 18 software boxes Date (bulk): Bulk, 1981-1993 Date (inclusive): 1979-1997 Abstract: The First Osborne Group (FOG) records contain software and documentation created primarily between 1981 and 1993. This material was created or authored by FOG members for other members using hardware compatible with CP/M and later MS and PC-DOS software. The majority of the collection consists of software written by FOG members to be shared through the library. Also collected are textual materials held by the library, some internal correspondence, and an incomplete collection of the FOG newsletters. creator: First Osborne Group. Processing Information Collection surveyed by Sydney Gulbronson Olson, 2017. Collection processed by Jack Doran, 2019. Access Restrictions The collection is open for research. Publication Rights The Computer History Museum (CHM) can only claim physical ownership of the collection. Users are responsible for satisfying any claims of the copyright holder. Requests for copying and permission to publish, quote, or reproduce any portion of the Computer History Museum’s collection must be obtained jointly from both the copyright holder (if applicable) and the Computer History Museum as owner of the material. -

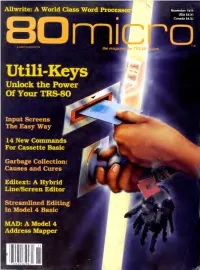

80 Microcomputing Magazine November 1984

Allwrite: A World Class Word Processo A CWC/I PUBLICATION Utili-Keys Unlock the Power Of Your TRS-80 Input Screens The Easy Way 14 New Commands For Cassette Basic Garbage Collection: Causes and Cures Editext: A Hybrid Line/Screen Editor Streamlined Editing In Model 4 Basi MAD: A Model 4 Address Mapper Knock The Socks Off Your Beef up Your Add a Low-Cost ^^ Color Computer with Personal Printer Radio Shack Accessories High-performance Using somebody else's home com- printing from your 1 puter can be a pretty frustrating Color Computer is fast thing. Tiny memories, second-rate and easy with the graphics and limited accessories DMP-110 dot-matrix take all the fun out of programming printer (#26-1271, p*^ and video games. That's why seri- $399.00) from Radio ous computer hobbyists enjoy Shack. The DMP-110 Radio Shack's Color Computer so gives you proportionally spaced or correspondence-quality ' much. No other color computer ex- characters for letters and reports at a swift 25 characters pands to do so many things. per second— about 200 words per minute! The DMP-110 Get Room to Grow With Disk Storage prints mono-spaced characters in standard, elite or con- densed fonts at 50 characters per second: fast enough to Add a single Radio Shack disk drive to your Color Com- print homework or reports in just minutes. The DMP-110 l»i'l • also offers all the print capabilities you need: italic charac- 5 1 /4" diskette. That s 156K of disk storage for $50 less ters, super and subscripts, underlining and microfonts.