On My Our Way”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stage Violence, Power and the Director an Examination

STAGE VIOLENCE, POWER AND THE DIRECTOR AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE by Jordan Matthew Walsh Bachelor of Philosophy, University of Pittsburgh, 2012 Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Pittsburgh in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Philosophy. The University of Pittsburgh May 2012 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS & SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jordan Matthew Walsh It was defended on April 13th, 2012 and approved by Jesse Berger, Artistic Director, Red Bull Theater Company Cynthia Croot, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Annmarie Duggan, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department Dr. Lisa Jackson-Schebetta, Assistant Professor, Theatre Arts Department 2 Copyright © by Jordan Matthew Walsh 2012 3 STAGE VIOLENCE AND POWER: AN EXAMINATION OF THE THEORY AND PRACTICE OF CRUELTY FROM ANTONIN ARTAUD TO SARAH KANE Jordan Matthew Walsh, BPhil University of Pittsburgh, 2012 This exploration of stage violence is aimed at grappling with the moral, theoretical and practical difficulties of staging acts of extreme violence on stage and, consequently, with the impact that these representations have on actors and audience. My hypothesis is as follows: an act of violence enacted on stage and viewed by an audience can act as a catalyst for the coming together of that audience in defense of humanity, a togetherness in the act of defying the truth mimicked by the theatrical violence represented on stage, which has the potential to stir the latent power of the theatre communion. I have used the theoretical work of Antonin Artaud, especially his “Theatre of Cruelty,” and the works of Peter Brook, Jerzy Grotowski, and Sarah Kane in conversation with Artaud’s theories as a prism through which to investigate my hypothesis. -

Annual Report 2018–2019 Artmuseum.Princeton.Edu

Image Credits Kristina Giasi 3, 13–15, 20, 23–26, 28, 31–38, 40, 45, 48–50, 77–81, 83–86, 88, 90–95, 97, 99 Emile Askey Cover, 1, 2, 5–8, 39, 41, 42, 44, 60, 62, 63, 65–67, 72 Lauren Larsen 11, 16, 22 Alan Huo 17 Ans Narwaz 18, 19, 89 Intersection 21 Greg Heins 29 Jeffrey Evans4, 10, 43, 47, 51 (detail), 53–57, 59, 61, 69, 73, 75 Ralph Koch 52 Christopher Gardner 58 James Prinz Photography 76 Cara Bramson 82, 87 Laura Pedrick 96, 98 Bruce M. White 74 Martin Senn 71 2 Keith Haring, American, 1958–1990. Dog, 1983. Enamel paint on incised wood. The Schorr Family Collection / © The Keith Haring Foundation 4 Frank Stella, American, born 1936. Had Gadya: Front Cover, 1984. Hand-coloring and hand-cut collage with lithograph, linocut, and screenprint. Collection of Preston H. Haskell, Class of 1960 / © 2017 Frank Stella / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 12 Paul Wyse, Canadian, born United States, born 1970, after a photograph by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders, American, born 1952. Toni Morrison (aka Chloe Anthony Wofford), 2017. Oil on canvas. Princeton University / © Paul Wyse 43 Sally Mann, American, born 1951. Under Blueberry Hill, 1991. Gelatin silver print. Museum purchase, Philip F. Maritz, Class of 1983, Photography Acquisitions Fund 2016-46 / © Sally Mann, Courtesy of Gagosian Gallery © Helen Frankenthaler Foundation 9, 46, 68, 70 © Taiye Idahor 47 © Titus Kaphar 58 © The Estate of Diane Arbus LLC 59 © Jeff Whetstone 61 © Vesna Pavlovic´ 62 © David Hockney 64 © The Henry Moore Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York 65 © Mary Lee Bendolph / Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York 67 © Susan Point 69 © 1973 Charles White Archive 71 © Zilia Sánchez 73 The paper is Opus 100 lb. -

Notre Dame Daily 1923-12-02 (Volume 2, Number

. ' ; oi' ' .. :I' , .... ... ·, ~ . : . ' '" .. .. --- . ----·. ···: .. i l ·,.. J.,··. -· . .The DAILY~s--~roblem ·Fight for, not · again~t, _Is Nohe- Da~~·s. .··:; -your DAILY.- -It-is-· ~Problem.· . 'l · -· fighting for you . - . •e ' 'i ··.:·.<:I ... ; I ilil ·. •' I I I I ~' • .. ,. ·. yoL.2. N0.·41· r: UNIVERSITY OF ·NOTRE DAME;:-NO.TRE DAME, INDIANA; slJNbA.Y;· DECEMBER z, i9z:f ·· PRICE 4 CENTS I ... ·- ...... .. ~·-------~· ... t . '.• ~ ·.· ~~::: ·. t .. ·.' . ' J, •• p • •• Me(ropo_litclli ··club. 1 r·-:-"i~is~-~~~Ei~·.. T~Lio'6"- t JuniQ~ Stag Supper . ; .: :;:;·.,.cAMPus::·.. : :·Dance.·Tickets>Out! - to Be Held at LaSalle G,LEECLUB . ·; . ' ' . s· .. Tickets fpr 'u~e; Metr~politan' clu~' l The':~~~re_ ·?ain~ reserves· '?e- i. :.'The'' J.unior -'stag~suppet:, r _which ·. ·sy_.n_''_-A·:·_T_ .· .. H.._ .. dance t9 be l1eld in New Yor~·dur;- ·!feated..tlie UTn1vers1ty -ofd:Tolei:Ifot; j will :be·. given at. the: LaSalle ·hotel ;;1· C" :ing the. Chri:;;tmas ;vacation :will ·.be · k3 .1 ·to. 0 'at o1 edo yester ay: a - = on Dec.e~~~r 13, ,will. be th~ ou~ _ -·.JO- ENTERTAIN . · · . .. · placed on sale .. Monday. -The tickets ·j ernoon: · '· · ·: ·· · · · ..· · ·': '!; 1 standing ev.ent .. of 'the .post-Thanks- Feel rather rem:iniscent this may be . prdcur~d . from : Josepl). : ·The following members··of the! giving .season.. .'~he affair is plan- Burke~ 427 Walsh hall, or·from any ! va'rsity squad made the trip: r hed ·,to_ 'cl-eat a better -spirit of fel- Will Appear in Mishawaka on D.ei:.· morrin~. -o- ~o- of 'the ~e~l:ie~s· o( the (!lub,. / Th~? ·! .. FrisJ<e~·. Roux, -R6ach1: Nugent~ i ;lows~ip:'~m<;>pg the m~mbers of .the .·. -

Wegohealthchat Transcript

#WEGOHealthChat Transcript Healthcare social media transcript of the #WEGOHealthChat hashtag. Tue, March 13th 2018, 12:50PM – Tue, March 13th 2018, 2:10PM (America/Detroit). See #WEGOHealthChat Influencers/Analytics. Sign up for FREE Symplur Account Create Transcripts with Custom Dates Get Custom Influencer Lists 3x Hashtag Search Results Sign Up Now WEGO Health @wegohealth 7 days ago It's the final countdown. 10 min until we start chatting with @simonrstones and @mikeveny about combating the stigma of chronic illness. #wegohealthchat Simon Stones @simonrstones 7 days ago RT @abrewi3010: @Lacktman @AmolUtrankar @chrissyfarr @StanfordMedX @larrychu You ever participated in twitter chats like #patientchat, #wtf… Mike Veny @mikeveny 7 days ago RT @wegohealth: It's the final countdown. 10 min until we start chatting with @simonrstones and @mikeveny about combating the stigma of chr… Candace @rarecandace 7 days ago RT @wegohealth: If you're unfamiliar with #WEGOHealthChat, here's a great reference guide to get you started! https://t.co/MqDpALi1xs h… Simon Stones @simonrstones 7 days ago Super excited for today's #WEGOHealthChat - starting in 10 minutes! Grab a cuppa, find a comfy spot, and get ready for a great hour with like minded people https://t.co/b1iWX2P1JQ Simon Stones @simonrstones 7 days ago RT @wegohealth: It's the final countdown. 10 min until we start chatting with @simonrstones and @mikeveny about combating the stigma of chr… Julie Cerrone Croner @justagoodlife 7 days ago RT @SimonRStones: Super excited for today's #WEGOHealthChat -

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's Truman Capote, 1958 I Am Always Drawn Back To

1 Breakfast at Tiffany's surrounded by photographs of ice-hockey stars, there is always a large bowl of fresh Truman Capote, 1958 flowers that Joe Bell himself arranges with matronly care. That is what he was doing when I came in. I am always drawn back to places where I have lived, the houses and their "Naturally," he said, rooting a gladiola deep into the bowl, "naturally I wouldn't have neighborhoods. For instance, there is a brownstone in the East Seventies where, got you over here if it wasn't I wanted your opinion. It's peculiar. A very peculiar thing during the early years of the war, I had my first New York apartment. It was one room has happened." crowded with attic furniture, a sofa and fat chairs upholstered in that itchy, particular red "You heard from Holly?" velvet that one associates with hot days on a tram. The walls were stucco, and a color He fingered a leaf, as though uncertain of how to answer. A small man with a fine rather like tobacco-spit. Everywhere, in the bathroom too, there were prints of Roman head of coarse white hair, he has a bony, sloping face better suited to someone far ruins freckled brown with age. The single window looked out on a fire escape. Even so, taller; his complexion seems permanently sunburned: now it grew even redder. "I can't my spirits heightened whenever I felt in my pocket the key to this apartment; with all its say exactly heard from her. I mean, I don't know. -

Men's Glee Repertoire (2002-2021)

MEN'S GLEE REPERTOIRE (2002-2021) Ain-a That Good News - William Dawson All Ye Saints Be Joyful - Katherine Davis Alleluia - Ralph Manuel Ave Maria - Franz Biebl Ave Maria - Jacob Arcadet Ave Maria - Joan Szymko Ave Maris Stella - arr. Dianne Loomer Beati Mortui - Fexlix Mendelssohn Behold the Lord High Executioner (from The Mikado )- Gilbert and Sullivan Blades of Grass and Pure White Stones -Orin Hatch, Lowell Alexander, Phil Nash/ arr. Keith Christopher Blagoslovi, dushé moyá Ghospoda - Mikhail Mikhailovich Ippolitov-Ivanov Blow Ye Trumpet - Kirke Mechem Bright Morning Stars - Shawn Kirchner Briviba – Ēriks Ešenvalds Brothers Sing On - arr. Howard McKinney Brothers Sing On - Edward Grieg Caledonian Air - arr. James Mullholland Come Sing to Me of Heaven - arr. Aaron McDermid Cornerstone – Shawn Kirchner Coronation Scene (from Boris Goudonov ) - Modest Petrovich Moussorgsky Creator Alme Siderum - Richard Burchard Daemon Irrepit Callidu- György Orbain Der Herr Segne Euch (from Wedding Cantata ) - J. S. Bach Dereva ni Mungu – Jake Runestad Dies Irae - Z. Randall Stroope Dies Irae - Ryan Main Do You Hear the Wind? - Leland B. Sateren Do You Hear What I Hear? - arr. Harry Simeone Down in the Valley - George Mead Duh Tvoy blagi - Pavel Chesnokov Entrance and March of the Peers (from Iolanthe)- Gilbert and Sullivan Five Hebrew Love Songs - Eric Whitacre For Unto Us a Child Is Born (from Messiah) - George Frideric Handel Gaudete - Michael Endlehart Git on Boa'd - arr. Damon H. Dandridge Glory Manger - arr. Jon Washburn Go Down Moses - arr. Moses Hogan God Who Gave Us Life (from Testament of Freedom) - Randall Thompson Hakuna Mungu - Kenyan Folk Song- arr. William McKee Hark! I Hear the Harp Eternal - Craig Carnahan He’s Got the Whole World in His Hands - arr. -

Glee: Uma Transmedia Storytelling E a Construção De Identidades Plurais

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DA BAHIA INSTITUTO DE HUMANIDADES, ARTES E CIÊNCIAS PROGRAMA MULTIDISCIPLINAR DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM CULTURA E SOCIEDADE ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Salvador 2012 ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação apresentada ao Programa Multidisciplinar de Pós-graduação, Universidade Federal da Bahia, como requisito parcial para obtenção do título de mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, área de concentração: Cultura e Identidade. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler Salvador 2012 Sistema de Bibliotecas - UFBA Lima, Roberto Carlos Santana. Glee : uma Transmedia storytelling e a construção de identidades plurais / Roberto Carlos Santana Lima. - 2013. 107 f. Inclui anexos. Orientador: Prof. Dr. Djalma Thürler. Dissertação (mestrado) - Universidade Federal da Bahia, Faculdade de Comunicação, Salvador, 2012. 1. Glee (Programa de televisão). 2. Televisão - Seriados - Estados Unidos. 3. Pluralismo cultural. 4. Identidade social. 5. Identidade de gênero. I. Thürler, Djalma. II. Universidade Federal da Bahia. Faculdade de Comunicação. III. Título. CDD - 791.4572 CDU - 791.233 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ROBERTO CARLOS SANTANA LIMA GLEE: UMA TRANSMEDIA STORYTELLING E A CONSTRUÇÃO DE IDENTIDADES PLURAIS Dissertação aprovada como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Cultura e Sociedade, Universidade Federal da Bahia, pela seguinte banca examinadora: Djalma Thürler – Orientador ------------------------------------------------------------- -

As Heard on TV

Hugvísindasvið As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Janúar 2013 2 Háskóli Íslands Hugvísindasvið Enska As Heard on TV A Study of Common Breaches of Prescriptive Grammar Rules on American Television Ritgerð til BA-prófs í Ensku Ragna Þorsteinsdóttir Kt.: 080288-3369 Leiðbeinandi: Pétur Knútsson Janúar 2013 3 Abstract In this paper I research four grammar variables by watching three seasons of American television programs, aired during the winter of 2010-2011: How I Met Your Mother, Glee, and Grey’s Anatomy. For background on the history of prescriptive grammar, I discuss the grammarian Robert Lowth and his views on the English language in the 18th century in relation to the status of the language today. Some of the rules he described have become obsolete or were even considered more of a stylistic choice during the writing and editing of his book, A Short Introduction to English Grammar, so reviewing and revising prescriptive grammar is something that should be done regularly. The goal of this paper is to discover the status of the variables ―to lay‖ versus ―to lie,‖ ―who‖ versus ―whom,‖ ―X and I‖ versus ―X and me,‖ and ―may‖ versus ―might‖ in contemporary popular media, and thereby discern the validity of the prescriptive rules in everyday language. Every instance of each variable in the three programs was documented and attempted to be determined as correct or incorrect based on various rules. Based on the numbers gathered, the usage of three of the variables still conforms to prescriptive rules for the most part, while the word ―whom‖ has almost entirely yielded to ―who‖ when the objective is called for. -

The Glee News

Inside:The Times of Glee Fox to end ‘Glee’? Kurt Hummel recieves great reviews on his The co-creator of Fox’s great acting, sining, and “Glee” has revealed dancing in his debut “Funny Girl” star Rachel Berry is photographed on the streets of New York plans to end the series, role of “Peter Pan”. walking five dogs. She will soon drop the news about her dog adoption Us Weekly reports. Ryan event. Murphy told reporters Wednesday in L.A. that the musical series will New meaning to “dog eats end its run next year after six seasons. The end of the show ap- dog” business pears to be linked to the Rising actors Berry and Hummel host Brod- death of Cory Monteith, one of its stars. Chris Colfer expands way themed dog show In the streets of New York, happy to be giving back. “After the emotional his talent from simple the three-legged dog to the Rachel uncertainly leads mother and her son. The three friends share a memorial episode for an actor and musician a dozen dogs on leads group hug, happily. Monteith and his char- to a screenplay wiriter through the street. Blaine Sam suggests to Mercedes acter Finn Hudson aired and Artie have positioned that they give McCo- “Old Dog New Tricks” is as well. last week, Murphy said themselves among some naughey to someone at the written by Chris Colfer, who it’s been very difficult to event, but Mercedes tells lunching papparazi, and claims his “two favorite move on with the show,” him to not bother - they’re loudly announce her arriv- cording things in life are animals the story reports. -

US, JAPANESE, and UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, and the CONSTRUCTION of TEEN IDENTITY By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by British Columbia's network of post-secondary digital repositories BLOCKING THE SCHOOL PLAY: US, JAPANESE, AND UK TELEVISUAL HIGH SCHOOLS, SPATIALITY, AND THE CONSTRUCTION OF TEEN IDENTITY by Jennifer Bomford B.A., University of Northern British Columbia, 1999 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN ENGLISH UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN BRITISH COLUMBIA August 2016 © Jennifer Bomford, 2016 ABSTRACT School spaces differ regionally and internationally, and this difference can be seen in television programmes featuring high schools. As television must always create its spaces and places on the screen, what, then, is the significance of the varying emphases as well as the commonalities constructed in televisual high school settings in UK, US, and Japanese television shows? This master’s thesis considers how fictional televisual high schools both contest and construct national identity. In order to do this, it posits the existence of the televisual school story, a descendant of the literary school story. It then compares the formal and narrative ways in which Glee (2009-2015), Hex (2004-2005), and Ouran koukou hosutobu (2006) deploy space and place to create identity on the screen. In particular, it examines how heteronormativity and gender roles affect the abilities of characters to move through spaces, across boundaries, and gain secure places of their own. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract ii Table of Contents iii Acknowledgement v Introduction Orientation 1 Space and Place in Schools 5 Schools on TV 11 Schools on TV from Japan, 12 the U.S., and the U.K. -

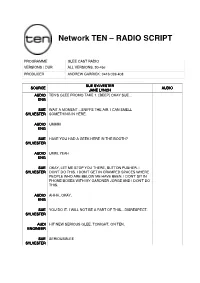

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT

Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT PROGRAMME GLEE CAST RADIO VERSIONS / DUR ALL VERSIONS. 30-45s PRODUCER ANDREW GARRICK: 0416 026 408 SUE SYLVESTER SOURCE AUDIO JANE LYNCH AUDIO TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] OKAY SUE… ENG SUE WAIT A MOMENT…SNIFFS THE AIR. I CAN SMELL SYLVESTER SOMETHING IN HERE. AUDIO UMMM ENG SUE HAVE YOU HAD A GEEK HERE IN THE BOOTH? SYLVESTER AUDIO UMM, YEAH ENG SUE OKAY, LET ME STOP YOU THERE, BUTTON PUSHER. I SYLVESTER DON'T DO THIS. I DON'T GET IN CRAMPED SPACES WHERE PEOPLE WHO ARE BELOW ME HAVE BEEN. I DON'T SIT IN PHONE BOXES WITH MY GARDNER JORGE AND I DON'T DO THIS. AUDIO AHHH..OKAY. ENG SUE YOU DO IT. I WILL NOT BE A PART OF THIS…DISRESPECT. SYLVESTER AUDI HIT NEW SERIOUS GLEE. TONIGHT, ON TEN. ENGINEER SUE SERIOUSGLEE SYLVESTER Network TEN – RADIO SCRIPT FINN HUDSON SOURCE AUDIO CORY MONTEITH FEMALE TEN'S GLEE PROMO TAKE 1. [BEEP] AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. THANKS. HI AUSTRALIA, IT'S FINN HUSON HERE, HUDSON FROM TEN'S NEW SHOW GLEE. FEMALE IT'S REALLY GREAT, AND I CAN ONLY TELL YOU THAT IT'S FINN COOL TO BE A GLEEK. I'M A GLEEK, YOU SHOULD BE TOO. HUDSON FEMALE OKAY, THAT'S PRETTY GOOD FINN. CAN YOU MAYBE DO IT AUDIO WITH YOUR SHIRT OFF? ENG FINN WHAT? HUDSON FEMALE NOTHING. AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY… HUDSON FEMALE MAYBE JUST THE LAST LINE AUDIO ENG FINN OKAY. UMM. GLEE – 730 TONIGHT, ON TEN. SERIOUSGLEE HUDSON FINN OKAY. -

14. Swan Song

LISA K. PERDIGAO 14. SWAN SONG The Art of Letting Go in Glee In its five seasons, the storylines of Glee celebrate triumph over adversity. Characters combat what they perceive to be their limitations, discovering their voices and senses of self in New Directions. Tina Cohen-Chang overcomes her shyness, Kurt Hummel embraces his individuality and sexuality, Finn Hudson discovers that his talents extend beyond the football field, Rachel Berry finds commonality with a group instead of remaining a solo artist, Mike Chang is finally allowed to sing, and Artie Abrams is able to transcend his physical disabilities through his performances.1 But perhaps where Glee most explicitly represents the theme of triumph over adversity is in the series’ evasion of death. The threat of death appears in the series, oftentimes in the form of the all too real threats present in a high school setting: car accidents (texting while driving), school shootings, bullying, and suicide. As Artie is able to escape his wheelchair to dance in an elaborate sequence, if only in a dream, the characters are able to avoid the reality of death and part of the adolescent experience and maturation into adulthood. As Trites (2000) states, “For many adolescents, trying to understand death is as much of a rite of passage as experiencing sexuality is” (p. 117). However, Glee is forced to alter its plot in season five. The season begins with a real-life crisis for the series; actor Cory Monteith’s death is a devastating loss for the actors, writers, and producers as well as the series itself.