Black and Brown Power in the Fight Against Poverty

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living for the City Donna Jean Murch

Living for the City Donna Jean Murch Published by The University of North Carolina Press Murch, Donna Jean. Living for the City: Migration, Education, and the Rise of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California. The University of North Carolina Press, 2010. Project MUSE. muse.jhu.edu/book/43989. https://muse.jhu.edu/. For additional information about this book https://muse.jhu.edu/book/43989 [ Access provided at 22 Mar 2021 17:39 GMT from University of Washington @ Seattle ] 5. MEN WITH GUNS In the aftermath of the Watts rebellions, the failure of community pro- grams to remedy chronic unemployment and police brutality prompted a core group of black activists to leave campuses and engage in direct action in the streets.1 The spontaneous uprisings in Watts called attention to the problems faced by California’s migrant communities and created a sense of urgency about police violence and the suffocating conditions of West Coast cities. Increasingly, the tactics of nonviolent passive resistance seemed ir- relevant, and the radicalization of the southern civil rights movement pro- vided a new language and conception for black struggle across the country.2 Stokely Carmichael’s ascendance to the chairmanship of the Student Non- violent Coordinating Committee SNCC( ) in June 1966, combined with the events of the Meredith March, demonstrated the growing appeal of “Black Power.” His speech on the U.C. Berkeley campus in late October encapsu- lated these developments and brought them directly to the East Bay.3 Local activists soon met his call for independent black organizing and institution building in ways that he could not have predicted. -

Extensions of Remarks 25081

September 10, 1969 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 25081 Col. Lawrence M cCeney Jones, Jr., xxx-xx-x... Col. Joseph Charles Fimiani, xxx-xx-xxxx , A rmy of the United S tates (lieutenant col- xxx-x... , A rmy of the United S tates (lieutenant A rmy of the United S tates (lieutenant colo- onel, U.S. Army) . colonel, U.S. A rmy). nel, U.S. Army) . Col. Rolland Valentine Heiser, xxx-xx-xxxx , Col. John Walter Collins III, xxx-xx-xxxx , A rmy of the United S tates (lieutenant colo- U.S. Army. CONFIRMATIONS nel, U.S. Army) . Col. T heme T roy E verton, xxx-xx-xxxx . Col. Harry E llsworth T abor, xxx-xx-xxxx , U.S. Army. E xecutive nominations confirmed by U.S. Army. Col. John Carpenter R aaen, Jr., xxx-xx-xxxx the Senate September 10, 1969: Col. William Holman Brandenburg, xxx-xx-x... xxx-... U.S. Army. U.S. ATTORNEYS xxx-... , U.S. Army. Col. Alvin Curtely Isaacs, xxx-xx-xxxx , U.S. Col. Harold Burton Gibson, Jr., Wayman G. Sherrer, of A labama, to be U.S. xxx-xx-xxxx Army. attorney for the northern district of A la- xxx-... , A rmy of the United S tates (lieutenant Col. Carl Vernon Cash, xxx-xx-xxxx , A rmy colonel, U.S. Army) . bama for the term of 4 years. of the United S tates (lieutenant colonel, Peter M ills, of M aine, to be U.S . attorney Col. John A lfred K jellstrom, xxx-xx-xxxx , U.S. Army). U.S. Army. for the district of M aine for the term of 4 Col. -

Malcolm X! Several Echools .~ ¢ §~ Inhonored Manhattan Thelate �;.,...R " Great Black Leaderon May19

REE@M GE ENFQAEN AN PMWAQY AQTS , /W6M /6 1»/#1 //% /45- F??? 925e-§7%,§¢»;: REL EEJAEI QB? ENWESYEGAFEEGN THE BEST QUPIES OBTAINABLE ARE TNQLTJDEE TN THE REPRQDTIQTTQN QF THE FKHJEO PAGES INCLUDED THAT ARE? BLURRED, LIGHT OR UTRTTTSE DTTTTCTJLT TU AD ARE THE RESULT GT THE CQNDITTGN AND QR QQLQR SF THE QRTGTNATS TROWDEBQ THE§E ARE THE BEST CGPTES AT/ATTJABLEE. 1 I Q"u 1-"' - '- Q .,_. ",¢ FILE. ocscnnmou sunsnu Fua SUBJECT 1]ALCQL[!l2§Lj,7T1_J;1,,W _ Fl LE NO._ A/Y/05-9711 m_U_,_ _____5£,,CT!0N _ 38__ { _ _55R/L5 65414" :1;_ _ _ /925! A 1? 0,5, The following documents are duplicate copies of other documents in the Headquarters or field office files. The documents in the left column have been withheld to save duplication costs for you and the FBI. The column on the right shows the location of the duplicate document that has been processed for your request. SAME AS 105~s999-6554, 105~a999-6581, 105-8999-6586 6555 1o5899965936582 10039932l-442 105~89996594 10039932l-446 100399321-447 100-399321-449 100-399321-450 L....1.*" '"-Qil:r1:5:L§*'~Q...'-1..-5.? L.-'4 _.-.1;-"" t-uh ""¢ie'-"E.-Ad-92-.s.}J.'.>.'-... mes ?-§ TO: SAC: *"~92""" 767.356v 5 53 Euquerque iL;§;§?.';Q.1. S 8232" _ ° _G Bgm [:1 Alexmdrin 1:] Jackson _n [I] ghh;}:192i':EPh1l 1:] Bonn. _ [:1 Anchorage 1:] Jaclu-omn_te E Pnugumh 1:] gm-asllm _ [:1 Ag*.nL5 B§lr.|_m<:re[:1 [:}l1 Knoxw a.n|a9C1e E9 Pom Richmmd-ad l:l {:1 E1-acgsCuenoa Alrea B ="="*"=" Q ::*::."::'1 S=¢""°"° 5 ..O:s,,n°"= E §,f?,";f£, E |_.L=_§n;:'i'e= E gznlfn C_ [:3 Madfid Q [£1 E1M 5:428:51 @>"'*;;:°B E E-5.m.:i.,*" San Diil [:3 %%:*:::mofui.-= Y v [3 B 0'8"! 1.-9. -

Seize the Time: the Story of the Black Panther Party

Seize The Time: The Story of the Black Panther Party Bobby Seale FOREWORD GROWING UP: BEFORE THE PARTY Who I am I Meet Huey Huey Breaks with the Cultural Nationalists The Soul Students Advisory Council We Hit the Streets Using the Poverty Program Police-Community Relations HUEY: GETTING THE PARTY GOING The Panther Program Why We Are Not Racists Our First Weapons Red Books for Guns Huey Backs the Pigs Down Badge 206 Huey and the Traffic Light A Gun at Huey's Head THE PARTY GROWS, ELDRIDGE JOINS The Paper Panthers Confrontation at Ramparts Eldridge Joins the Panthers The Death of Denzil Dowell PICKING UP THE GUN Niggers with Guns in the State Capitol Sacramento Jail Bailing Out the Brothers The Black Panther Newspaper Huey Digs Bob Dylan Serving Time at Big Greystone THE SHIT COMES DOWN: "FREE HUEY!" Free Huey! A White Lawyer for a Black Revolutionary Coalitions Stokely Comes to Oakland Breaking Down Our Doors Shoot-out: The Pigs Kill Bobby Hutton Getting on the Ballot Huey Is Tried for Murder Pigs, Puritanism, and Racism Eldridge Is Free! Our Minister of Information Bunchy Carter and Bobby Hutton Charles R. Garry: The Lenin of the Courtroom CHICAGO: KIDNAPPED, CHAINED, TRIED, AND GAGGED Kidnapped To Chicago in Chains Cook County Jail My Constitutional Rights Are Denied Gagged, Shackled, and Bound Yippies, Convicts, and Cops PIGS, PROBLEMS, POLITICS, AND PANTHERS Do-Nothing Terrorists and Other Problems Why They Raid Our Offices Jackanapes, Renegades, and Agents Provocateurs Women and the Black Panther Party "Off the Pig," "Motherfucker," and Other Terms Party Programs - Serving the People SEIZE THE TIME Fuck copyright. -

December 1966

Mr & Mrs. Grant c~nn<?~ 4907.Klat~e ROho~d 45244 20¢ Cinc:Lnnatl., :LO IN THIS ISSUE... DON'T BUY THE OAKLAND TRIB FREEDOM PRIMER MOVIE REVIEW: Losing Just The Same o o .c n. LOWNDES COUNTY NEGROES go to polls in Lowndesboro, Alabama, the first time they have voted in their lives. 1600 voted for the Lowndes County Freedom OrganizatiIJn candidates. L DES cau TY CAN IDATES. LOSE,. UT BLACK PANTHER STRONG The Lowndes County Freedom Organization, the only political party crowd, shaking hands, hugging and kissing TAX ASSESSOR in America controlled and organized by black people, was defeated in the people young and old (This sounds Alice L. MOJre (LCFO) 1604 sentimental: I put it in for the benefit of Charlie Sullivan (Dem) 2265 Lowndes County, Alabama last month. The LCFO, also known a s the those of our readers Who may think that TAX COLLECTOR Black Panther Party after its ballot symbol, a leaping black panther, was Black Power people are harsh and fright Frank Miles, Jr. (LCFO) 1603 organized a year and a half ago by Lowndes County residents and mem ening. In Lowndes, where Black Power Iva D. Sullivan (D,~m) 2268 bers of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. began, it is black people together. "It is BOARD OF EDUCATION, PLACE #3 the will, the courage and the love in our Robert Logan (LCFO) 1664 Fear, intimidation, fraud and unpreparedness caused its defeat this hearts," said carmichae(in his speech.) David M. Lyon (Rep) 1937 Fall, but the LCFO' has proved to be a strong political organization. -

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature

Masaryk University Faculty of Education Department of English Language and Literature The armed struggle from Oakland Diploma thesis Brno 2018 Supervisor: Author: Michael George, M. A. Bc. Jan Hudeček Prohlášení: Slavnostně prohlašuji, že jsem tuto diplomovou práci vypracoval samostatně, pracující pouze se zdroji, které jsou uvedeny. Souhlasím s tím, že tato práce bude uložena v knihovně Pedagogické fakulty Masarykovy university a bude přístupná pro studijní účely všech studentů Pedagogické fakulty. V Brně 21. února 2018 …………………… Bc. Jan Hudeček Declaration: I solemnly declare that I had carried out this diploma thesis independently, only working with the listed sources. I agree with this work being stored in the library of the Faculty of Education at Masaryk University and being accessible for study purposes to the students of the Faculty of Education. In Brno, 21st February 2018 …………………… Bc. Jan Hudeček Acknowledgments I would like to express my gratitude to my supervisor Michael George, M.A., for his notes, helpful advices and guidance through the process of writing my diploma thesis and to my family, who never stopped supporting me. Abstract The armed struggle from Oakland outlines the Black Panthers Party movement in USA from 1966 to 1972. Chapters of this thesis are chronologically describing the movement and the development of the Party in the USA, what were the most important events the party participated in and who were the most important members of the party. Anotace Diplomová práce 'The armed struggle from Oakland' ukazuje vývoj Black Panthers Party (Strany černých panterů) v USA mezi lety 1966 a 1972. Cílem této práce je uceleně popsat jak se strana během své existence vyvíjela, jaké byly její nejznámější akce a kdo byli nejznámější členové strany. -

Black Against Empire: the History and Politics of The

Praise for Black against Empire “This is the book we’ve all been waiting for: the first complete history of the Black Panther Party, devoid of the hype, the nonsense, the one-dimensional heroes and villains, the myths, or the tunnel vision that has limited scholarly and popular treatments across the ideological spectrum. Bloom and Martin’s riveting, nuanced, and highly original account revises our understanding of the Party’s size, scope, ideology, and political complexity and offers the most compelling explanations for its ebbs and flows and ultimate demise. Moreover, they reveal with spectacular clarity that the Party’s primary target was not just police brutality or urban poverty or white supremacy but U.S. empire in all of its manifestations.” — Robin D. G. Kelley, author of Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination “As important as the Black Panthers were to the evolution of black power, the African American freedom struggle, and, indeed, the sixties as a whole, scholarship on the group has been surprisingly thin and all too often polemical. Certainly no definitive scholarly account of the Panthers has been produced to date or rather had been produced to date. Bloom and Martin can now lay claim to that honor. This is, by a wide margin, the most detailed, analytically sophisticated, and balanced account of the organiza- tion yet written. Anyone who hopes to understand the group and its impact on American culture and politics will need to read this book.” — Doug McAdam, author of Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930–1970 “Bloom and Martin bring to light an important chapter in American history. -

The Life and Works of Huey P. Newton, Founder of the Black Panther Party

“War against the Panthers”: The Life and Works of Huey P. Newton, Founder of the Black Panther Party By Hugo Turner Region: USA Global Research, September 04, 2016 Theme: History, Police State & Civil Rights Dedicated to My Friend and Comrade Marland X aka @CharlieMBrownX Huey P. Newton was a visionary, a poet, a thinker, a writer, a gangster, but above all a revolutionary. Without his brilliance and daring the Black Panther party would never have been created. 50 Years after it’s creation the Black Panther Party for Self Defense is as relevant as ever because shockingly little has changed except for the worse. Black life is as cheap as ever, police gun down people at an alarming rate. Much of the country lives in poverty while the ultra-rich get ever richer. In Huey’s time American Imperialism was waging a genocidal war across south-east Asia spanning Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, and Indonesia. (and other places as well) Today American imperialism is waging an even larger war stretching from central Africa, through southwest Asia(the middle east) , and into Central Asia and even eastern Europe (Ukraine). Police brutality, poverty, war, have only grown worse. In fact the Obama administration oversaw the greatest economic looting of the country in general and the black community in particular in american history. Capitalism is in Crisis, Imperialism is out of control, and once again revolution is in the air. Thus now the year of the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Black Panther Party on October 15 1966 (Or more likely October 29th) is the perfect time to revive the heroic figure of Huey P. -

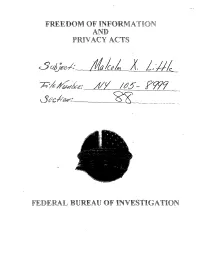

Special Access and FOIA, FOIA Requests For

Case Id Date Received Date Closed Requester Name Subject Disposition Description Department of Justice (DOJ) Case File 169-26-1, Section 1 in box 28 of 48885 Jan/04/2016 Jan/20/2016 Ahmed Young Class 169: Desegregation of Public Education Total grant 48886 Jan/04/2016 Jan/21/2016 Jared Leighton Mark Clark, 44-HQ-44202, 157-SI-802 Request withdrawn Other all FBI personnel and case records for retired Special Agenct Edmund F. 48891 Jan/05/2016 Jan/12/2016 Devin Murphy Murphy who served in DC, NC, Missouri field offices Other Other 48893 Jan/05/2016 Jan/22/2016 (b) (6) (b) (6) Partial grant 48894 Jan/05/2016 Feb/03/2016 Jared McBride IRR files Total grant 48895 Jan/05/2016 Jun/09/2016 Conor Gallagher FBI file numbers 100-AQ-3331 regarding the Revolutionary Union Request withdrawn Other FBI Field Office case files regarding the Revolutionary Union 100-RH-11090 Springfield 100-11574 Richmond 100-11090 48896 Jan/05/2016 Conor Gallagher Dallas 100-12360 FBI file numbers regarding the October League aka Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) New York 100-177151 Detroit 100-41416 48897 Jan/05/2016 Conor Gallagher Baltimore 100-30603 FBI Case Number 100-HQ-398040, 100-NY-109682, 100-LS-3812. Leon 48900 Jan/06/2016 Jan/26/2018 Parker Higgins Bibb Partial grant FBI Case File 100-CG-42241, 100-NY-151519, 100-NY-150205, 100-BU- 48902 Jan/06/2016 Kathryn Petersen 439-369. FBI Case File 100-HQ-426761 and 100-NY-141495. Nonviolent Action 48903 Jan/06/2016 Mar/02/2016 Mikal Jakubal Against Nuclear Weapons. -

The Black Panther Party's Revolutionary Identity and the People's Campaign of 1973

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2021-01-20 The Ballot before the Bullet: The Black Panther Party's Revolutionary Identity and the People's Campaign of 1973 Grabia, Kayla Grabia, K. (2021). The Ballot before the Bullet: The Black Panther Party's Revolutionary Identity and the People's Campaign of 1973 (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113010 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Ballot before the Bullet: The Black Panther Party’s Revolutionary Identity and the People’s Campaign of 1973 by Kayla Grabia A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN HISTORY CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2021 © Kayla Grabia 2021 Abstract Historical analysis of the Black Panther Party (BPP) has primarily concentrated on the founding of the organization in 1966 till 1971 when two key leaders– Huey P. Newton and Eldridge Cleaver— disagreed about the use of self-defence as the organization’s sole revolutionary strategy. This moment, popularly known as the Split, marked the beginning of a new era of the Panthers, led by Newton, that pursued revolutionary change through mainstream electoral politics. -

The Movement, May 1967. Vol. 3 No. 5

IN THIS ISSUE HARLEM AGAINST THE DRAFT LETTERS FROM HANOI HOW DO WE STOP THE WAR? VOLUME 3 NO:5 BLACK STUDENTS ON THE MOVE Across the country and particularly in the South a new black student move ment. is taking shape. Howard University s,tudents ran General Hershey off a speakers platform at their school in protest of .the Vietnam War and the draft. They are now fighting compulsory ROtC. At Southern University in Louisiana black students have been demonstrating for changes .in dorm rules, rules about cars, and for changes in faculty hiring practices. During one of" the d'emonstra tions a campus cop went berserk and shot artd wounded five students. He is being charged with aggravated assault. Below we give accounts of the' activity in Nash- ville and at Texas Southern University. .' RIOT COPS bust black student after police attacked Fisk dorms. Hopefully, this new militant black student movement 'will have the effect of giving new vitality t~' the predominately white student movement. Already, we think the students at Howard University hav~ taught something to activists at NASHVILLE Berkeley and elsewhere. You don't sit still for Government speakers so they can give their side. The Howard students realize clearly that the governJIlent's point of view 'completely dominates all the news sources ,of the country. Has the Pres-. ident ever given ·equal time to the anti-war movement on any of his prime tele casts to the nation? To speak of free speech, when the government has control COPS ATTACK of all sources of communication, is to play the fool. -

Chronologie Provisoire Du

Chronologie (provisoire) du Black Panther Party et des principaux événements qui ont influencé ses activités aux Etats-Unis de 1966 à 1982 Nous avons placé en encadré et en italiques les éléments du contexte social et politique qui ont influencé la naissance du Parti des Panthères noires, son ascension puis son déclin. 1954 : La Cour suprême prend position dans l’affaire Brown contre le ministère de l’Education et déclare la ségrégation illégale sur tout le territoire américain, ce qui va déclencher des centaines de mouvements, notamment dans le Sud, pendant la décennie suivante. 1955 : Le boycott des bus de Montgomery commence et va durer 13 mois. Août 1955 : Lynchage d’un adolescent de 14 ans : Emmett Till. Les photos de son corps torturé créent un choc considérable dans les communautés afro-américaines et un sentiment de colère et de révolte pousse de nombreux Afro-Américains à s’engager politiquement. 1957 : Malcolm X adhère à la Nation de l’Islam. Martin Luther King crée la Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). 1959 : début de «l’engagement» américain au Vietnam qui durera jusqu’en 1975. 1959 : A l’âge de 18 ans, George Jackson est condamné à une peine allant d’un an à la prison à vie, pour avoir volé 70 dollars. Il ne sera jamais libéré avant son assassinat en taule le 21 août 1971. 1960 : Fondation du Negro American Labor Council (NALC, Conseil des travailleurs noirs américains) qui vise à fusionner les efforts des syndicalistes de base et des mouvements des droits civiques. De nombreux petits groupes nationalistes afro-américains se créent à la même époque, lors de scissions de la Nation de l’Islam.