Parliamentary Privilege and Individual Members

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Terrorist Speech and the Future of Free Expression

TERRORIST SPEECH AND THE FUTURE OF FREE EXPRESSION Laura K. Donohue* Introduction.......................................................................................... 234 I. State as Sovereign in Relation to Terrorist Speech ...................... 239 A. Persuasive Speech ............................................................ 239 1. Sedition and Incitement in the American Context ..... 239 a. Life Before Brandenburg................................. 240 b. Brandenburg and Beyond................................ 248 2. United Kingdom: Offences Against the State and Public Order ....................................................................... 250 a. Treason............................................................. 251 b. Unlawful Assembly ......................................... 254 c. Sedition ............................................................ 262 d. Monuments and Flags...................................... 268 B. Knowledge-Based Speech ................................................ 271 1. Prior Restraint in the American Context .................... 272 a. Invention Secrecy Act...................................... 274 b. Atomic Energy Act .......................................... 279 c. Information Relating to Explosives and Weapons of Mass Destruction............................................ 280 2. Strictures in the United Kingdom............................... 287 a. Informal Restrictions........................................ 287 b. Formal Strictures: The Export Control Act ..... 292 II. State in -

The Parliamentary Bypass Operation

The parliamentary bypass operation by Labour MP Robert Sheldon - reported to This is the story of a scandal. The government has failed to account to Parliament that they wished to 'reaffirm the Parliament for expenditure of half a billion pounds on a secret 'spy' satellite, importance' they attached to the statement 'as a due to be positioned over the Soviet Union. In doing so, it has flagrantly breached means of keeping Parliament reliably informed about the costs and progress of major Defence a solemn promise to inform Parliament, through its public Accounts Committee, projects' . of all major defence expenditure. This was to be the subject of the first At the time the agreement was made in 1982, Sheldon's predecessor as chair of the PAC, Lord programme in a forthcoming BBC2 series Secret Society, written and presented Barnett, wrote that 'full accountability to by New Statesman writer DUN CAN CAMPBELL. Last Thursday, BBC Parliament in future is imperative'. Yet within a year, the government was breaking that agreement director general Alasdair Milne banned the programme. Here, for the first time, by secretly developing Zircon. Campbell is able to tell the story of official deceit. (Additional research by Lord Barnett, ironically, is now the Deputy Chairman of the BBC. The man who made the Jolyon Jenkins and Patrick Forbes) agreement with Barnett was Sir Frank Cooper - then the Ministry of Defence Permanent PROJECT ZIRCON is the secret codename for Permanent Secretaries' Committee on the Secretary, but now a late convert to campaigning Britain's first ever spy satellite. Zircon, originally Intelligence Services (PSIS), and would have then for Freedom of Information and better planned to be launched in 1988, will be a 'signals been passed to the Prime Minister. -

UK Eyes Alpha by the Same Author UK Eyes Alpha Big Boys' Rules: the SAS and the Secret Struggle Against the IRA Lnside British Lntelligence

UK Eyes Alpha By the same author UK Eyes Alpha Big Boys' Rules: The SAS and the secret struggle against the IRA lnside British lntelligence Mark Urban tr firhrr anr/ fulrr' ft For Ruth and Edwin Contents lntroduction Part One The First published in I996 1 Coming Earthquake 3 and Faber Limited by Faber 2 A Dark and Curious Shadow 13 3 Queen Square London vcrN JAU 3 The Charm Offensive 26 Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd Printed in England by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc 4 Most Ridiculed Service 42 All rights reserved 5 ZIRCON 56 O Mark Urban, 1996 6 Springtime for Sceptics 70 Mark Urbar-r is hereby identified as author of 7 A Brilliant Intelligence Operation 84 this work in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 8 The \7all Comes Tumbling Down 101 A CIP rccord for this book is available from the Part Two British Library 9 Supergun LL7 tsnN o-57r-r7689-5 10 Black Death on the Nevsky Prospekt L29 ll Assault on Kuwait L43 12 Desert Shield 153 13 Desert Storm 165 14 Moscow Endgame LA2 Part Three l5 An Accidcnt of History L97 l(r Irrlo thc ll:rllirrn 2LO tt),)B / (,1,1 l, I Qulgrnirc 17 Time for Revenge 22L lntroduction 18 Intelligence, Power and Economic Hegemony 232 19 Very Huge Bills 245 How good is British intelligence? What kind of a return do ministers and officials get 20 The Axe Falls 2il for the hundreds of millions of pounds spent on espionage each year? How does this secret establishment find direction and purpose 2l Irish Intrigues 269 in an age when old certainties have evaporated? Very few people, even in Conclusion 286 Whitehall, would feel confident enough to answer these questions. -

APR 2017-07 Winter Cover FA.Indd

Printer to adjust spine as necessary Australasian Parliamentary Review Parliamentary Australasian Australasian Parliamentary Review JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP Editor Colleen Lewis Fifty Shades of Grey(hounds) AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 Federal and WA Elections Off Shore, Out of Reach? • VOL 32 NO 32 1 VOL AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 • VOL 32 NO 1 • RRP $A35 AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP (ASPG) AND THE AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW (APR) APR is the official journal of ASPG which was formed in 1978 for the purpose of encouraging and stimulating research, writing and teaching about parliamentary institutions in Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific Membership of the Australasian Study of (see back page for Notes to Contributors to the journal and details of AGPS membership, which includes a subscription to APR). To know more about the ASPG, including its Executive membership and its Chapters, Parliament Group go to www.aspg.org.au Australasian Parliamentary Review Membership Editor: Dr Colleen Lewis, [email protected] The ASPG provides an outstanding opportunity to establish links with others in the parliamentary community. Membership includes: Editorial Board • Subscription to the ASPG Journal Australasian Parliamentary Review; Dr Peter Aimer, University of Auckland Dr Stephen Redenbach, Parliament of Victoria • Concessional rates for the ASPG Conference; and Jennifer Aldred, Public and Regulatory Policy Consultant Dr Paul Reynolds, Parliament of Queensland • Participation in local Chapter events. Dr David Clune, University of Sydney Kirsten Robinson, Parliament of Western Australia Dr Ken Coghill, Monash University Kevin Rozzoli, University of Sydney Rates for membership Prof. Brian Costar, Swinburne University of Technology Prof. -

Oxford DNB: January 2021

Oxford DNB: January 2021 Welcome to the seventieth update of the Oxford DNB, which adds biographies of 241 individuals who died in the year 2017: 224 with their own entries and seventeen added to existing entries as 'co-subjects'. Of these new inclusions, the earliest born is the journalist Clare Hollingworth (1911-2017) and the latest born is the artist and photographer Khadija Saye (1992- 2017). Hollingworth is one of five centenarians included in this update, and Saye one of thirty-four new subjects born after the Second World War. The vast majority (169, or over 70%) were born in the 1920s and 1930s. Sixty-three of the new subjects who died in 2017 (or just over 26% of the cohort) are women. Twenty of the new subjects were themselves contributors to the dictionary. Forty-five of the new articles include portrait images. From January 2021, the Oxford DNB offers biographies of 64,071 men and women who have shaped the British past, contained in 61,745 articles. 11,870 biographies include a portrait image of the subject—researched in partnership with the National Portrait Gallery, London. As ever, we have a free selection of these new entries, together with a full list of the new biographies. Most public libraries across the UK subscribe to the Oxford DNB, which means you can access the complete dictionary for free via your local library. Libraries offer 'remote access' that enables you to log in at any time at home (or anywhere you have internet access). Elsewhere the Oxford DNB is available online in schools, colleges, universities, and other institutions worldwide. -

Felix Issue 758, 1987

The Newspaper Of Imperial College Union Founded 1949 Bottle match ban threat Mines be informed of the feelings of Camborne School of Mines will not be invited back to Imperial the Union General Meeting on ICU and how their behaviour at future Tuesday. After further discussion, College for the annual 'Bottle Match' unless their behaviour visits will effect subsequent fixtures. UGM Chairman Hugh Southey improves. Monday's meeting of ICU Council decided that A further ammendment, prepared by suspended standing orders, thereby Camborne should be sent a warning, after players and Gareth Fish, added that "failure to preventing a quorum call, and took supporters disrupted the Union Bar and Southside Bar and improve behaviour at the next visit an "opinion vote" from the meeting. will result in a withdrawal of On the question of whether Camborne were believed to have vandalised toilets in the Sherfield Building reciprocal agreements." This should be banned from IC Union and on Saturday night. ammendment was accepted by Mr all College bars, the 'informal Camborne students have a history past, be included in this ban. She Perry and the proposal was passed. meeting' voted 58 for a ban, with 37 of abusive behaviour and petty added that the cleaners had Ms Peirce raised the issue again at against. vandalism during their biannual trips complained about the state of the to IC to play rugby, football, hockey Union building on Monday morning. and squash against the RSM. Two RSMU President Rob Perry years ago, after the sporting fixtures stressed that the Camborne fixture had to be cancelled, Camborne caused was one of the oldest varsity fixtures, several hundred pounds worth of and that the rowdy behaviour had not damage in the RSM building and in been excessive. -

Alastair Milne Is Asked to Resign As Director-General of the BBC

The Zircon Affair 1986-7 A BBC investigation into state secrets culminates in a Special Branch raid on BBC offices, finally bringing down Director General Alasdair Milne. By David Wilby Zircon was the name of a secret spy satellite being developed under the Conservative Government. It aimed to monitor communications from the Soviet Union and its existence – and its £500 million cost – were exposed by the investigative journalist Duncan Campbell. In a BBC programme he alleged that the project had been kept hidden from Parliament and from its powerful financial watchdog the Public Accounts Committee. Campbell had a long history of embarrassing governments by uncovering their secrets. He was still best known for being a defendant in the so-called “ABC Case” in 1978, in which he was tried under the Official Secrets Act. This was a cause célèbre among the libertarian Left and was so called because of the initials of Campbell and his co-defendants Crispin Aubrey, a fellow journalist, and John Berry, a former soldier. The failure of the case led the Home Office to look again at the law. Since then, Campbell’s investigations had regularly appeared in the New Statesman and made him the scourge of the intelligence community. This was the figure commissioned by BBC2, in June 1985, to research and present a six-part series to be called Secret Society. When asked later about the decision to hire Campbell, the BBC2 Controller Graeme McDonald said he hadn’t imagined there would be a problem. The series was to be made by BBC Scotland, and even before details of the Zircon programme were finalised, Whitehall was worried. -

Don Hale 8 March 2019 4/12-5/4

IICSA Inquiry-Westminster 8 March 2019 1 Friday, 8 March 2019 1 until 2016, at the National Counter-terrorism Policing 2 (10.00 am) 2 Headquarters. He was tasked with searching both the 3 THE CHAIR: Good morning, everyone, and welcome to Day 5 of 3 Metropolitan Police Special Branch and the 4 this public hearing. Mr Altman? 4 Greater Manchester Police Special Branch records -- 5 MR ALTMAN: Mr Henderson. 5 that's both electronic and hard copy records -- for any 6 Witness statements adduced by MR HENDERSON 6 documents relating to a search of the offices of 7 MR HENDERSON: Good morning, chair. Chair and panel, you 7 Mr Donald Hale or the Bury Messenger newspaper in or 8 will recall that yesterday afternoon we heard evidence 8 around 1984. 9 from Commander Jerome in relation to the series of 9 Chair, you will appreciate that that is going to be 10 allegations that have been made about Elm Guest House. 10 very relevant to the evidence that you are about to hear 11 We just wanted to invite you to formally adduce some 11 from Mr Hale. 12 press articles and a clip from a documentary, a Panorama 12 Mr Blackford's witness statement indicates that 13 documentary, that dealt with those allegations. There 13 nothing has been found in either of those searches in 14 is no need to bring these up on screen, but they will be 14 the records. However, if we could turn, please, to 15 on the inquiry website. They are INQ004082; INQ004074; 15 page 2, and zoom in on paragraphs 1.5 and 1.6, he 16 INQ004093; and INQ004095. -

The Cost of Zircon

: The cost of Zircon A 'get-out' clause now supposedly present exploratory phase.' An MoD press officer knew about Zircon either (except for Ministers). allows the government to keep added that 'the phrase exploratory means we Zircon was secret from Parliament, until the BBC could not really be in the business of contracts.' told them about it. Parliament in the dark about projects Some 'Whitehall sources' even suggested, two Point 3: should Parliament have been told? The like Zircon. DUN CAN CAMP BELL weeks later, that Zircon had been cancelled. formal criteria which determine when Professed official uncertainty about an information about a major defence project should explains why the get-out doesn't work 'experimental' project stands in dramatic contrast be passed to the Public Accounts Committee is to the fervour of the government's denunciation loosely called the 'Chevaline' agreement, drawn ONE MONTH AGO, the New Statesman of 'traitors' who have allegedly leaked the up in 1982after a decade in which Parliament had published the controversial article on Project precious Zircon secret. But there is nothing not been informed of the huge cost overruns of the Zircon. Although the NS report has since been 'preliminary' or 'experimental' about Zircon - 'Chevaline' , or Polaris modernisation misrepresented as the gratuitous 'blowing' of an save that every satellite is preliminary and indeed programme. The information comes to the PAC important secret, its central thrust was the exp .nental until a rocket has safely taken it in in the form of an annual Major Projects disclosure of the deliberate deception of orbit around the earth. -

Index on Censorship

Index on Censorship http://ioc.sagepub.com/ Paradoxes of secrecy Duncan Campbell Index on Censorship 1988 17: 16 DOI: 10.1080/03064228808534500 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ioc.sagepub.com/content/17/8/16 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com On behalf of: Writers and Scholars International Ltd Additional services and information for Index on Censorship can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ioc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ioc.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav >> Version of Record - Sep 1, 1988 What is This? Downloaded from ioc.sagepub.com by Natasha Schmidt on April 9, 2013 INDEX ON CENSORSHIP 8/88 Duncan Campbell Paradoxes of secrecy The Prime Minister and her officials are utterly disdainful of press freedom, open government or the American concept of the press as 'fourth estate' Freedom of speech and journalistic But juries and many judges have never possibility of similar domestic political pluralism, which survived and occasionally liked the law. When journalists or activities in Britain. In 1975/76, the author thrived in Britain in the first half of the 'whistleblowers' (confidential sources or became part of this largely left-oriented 1980s has since then been debased and informants) have made disclosures in the interest. abused with increasing frequency. For the public interest, successive trials (including Although such activities as reporting the moment the UK cannot bear comparison my own trial on secrecy charges, ten years role of the CIA in Britain were not visibly with many governments' violent or ago) have shown that they are unlikely to opposed at the time by legal or security murderous excesses against the press. -

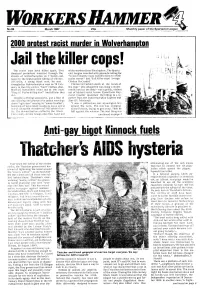

Jail the Killer Cops! ~ the Racist Cops Have Killed Again

N086 March 1987 20p Monthly paper of the Spartacist League c___ ... ~. _. ____"""" __ --.-"-_..........."...>-""'"'- =-< ..... "'JiO -:::oF ~_--. ,... .. ~~~~~_~~_~......,..,.v.~>ft_ =:4 _-,.. t~~ n 2QJO grotest racist murder in Wolv,rhamgton Jail the killer cops! ~ The racist cops have killed again. Two white workers from Birmingham. The Sparta tr, ~:~ cist League marched with placards calling for - thousand protesters marched through the ,~r :'7\. streets of Wolverhampton on 7 March, out "Union/minority mass mobilisations to crush raged by the brutal police killing of Clinton racist terror!" and "Jail killer cops! Avenge :\lcCurbin, a young black man. He was Clinton lVIcCurbin!'! strangled by Wolverhampton cops on 20 Feb Clinton l\lcCurbin's death at the hands of ruary in the city-centre "N ext" clothes shop. the cops - who alleged he was using a stolen Shocked bystanders cried out to the cops: credit card at the shop - was a grisly, violent "Stot:' ii:! You're killinfS him!" And kill him they act of blatant racist terror. Eyewitness Ray did. mond Coulter described the killing to a re Despite a driving snowstorm, and a flow of porter from the iVolverhampton Express and intimidating and provocative police warnings Star (21 rebruarv): about "agitators" coming to "cause trouble", "I saw a poli~eman run up and grab him hundreds of local black residents came out to around the neck. The man was swinging nwt'd~ alcngside members of 1\lcCurbin's fam himself round, trying to get away. Then he ily. The demonstration, called by the Black fell against the window. The next thing was Community Action Group, also drevJ Asian and continued on page 2 ~-,.,~...,._,-.