Maureen Linton, President 2006-2008 the FELL and ROCK JOURNAL

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership Number: 3812 First Fell Climbed

My 214 Story Name: Christopher Taylor Membership number: 3812 First fell climbed: Coniston Old Man, 6 April 2003 Last fell climbed: Great End, 14 October 2019 I was a bit of a late-comer to the Lakes. My first visit was with my family when I was 15. We rented a cottage in Grange for a week at Easter. Despite my parents’ ambitious attempts to cajole my sister Cath and me up Scafell Pike and Helvellyn, the weather turned us back each time. I remember reaching Sty Head and the wind being so strong my Mum was blown over. My sister, 18 at the time, eventually just sat down in the middle of marshy ground somewhere below the Langdale Pikes and refused to walk any further. I didn’t return then until I was 28. It was my Dad’s 60th and we took a cottage in Coniston in April 2003. The Old Man of Coniston became my first summit, and I also managed to get up Helvellyn via Striding Edge with Cath and my brother-in-law Dave. Clambering along the edge and up on to the still snow-capped summit was thrilling. A love of the Lakes, and in particular reaching and walking on high ground, was finally born. Visits to the Lakes became more regular after that, but often only for a week a year as work and other commitments limited opportunities. A number of favourites established themselves: the Langdale Pikes; Lingmoor Fell; Catbells and Wansfell among them. I gradually became more ambitious in the peaks I was willing to take on. -

In Memoriam I Met Ralph in 1989 When I Moved to Wolverhampton, Through Our Involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- Eering Club

Obituaries Matterhorn. Edward Theodore Compton. 1880. Watercolour. 43 x 68cm. (Alpine Club Collection HE118P) 399 I N M E M ORI am 401 Ralph Atkinson 1952 - 2014 In Memoriam I met Ralph in 1989 when I moved to Wolverhampton, through our involvement with the Wolverhampton Mountain- eering Club. Weekends in Wales The Alpine Club Obituary Year of Election and day trips to Matlock and the (including to ACG) Roaches became the foundation for extended expeditions to the Ralph Atkinson 1997 Alps including, in 1991, a fine Una Bishop 1982 six-day ski traverse of the Haute John Chadwick 1978 Route, Argentière to Zermatt, John Clegg 1955 and ascents in 1993 of the Mönch Dennis Davis 1977 and Jungfrau. Descending the Gordon Gadsby 1985 Jungfrau in a storm, we could Johannes Villiers de Graaff 1953 barely see each other. I slipped David Jamieson 1999 in the new snow and had to self- Emlyn Jones 1944 arrest, aided by the tension in the Brian ‘Ned’ Kelly 1968 rope to Ralph. It worked, and I Neil Mackenzie Asp.2011, 2015 Ralph Atkinson climbing on the slabs of Fournel, was soon back on the ridge, but Richard Morgan 1960 near Argentière, Ecrins. (Andy Clarke) when we dropped below the John Peacock 1966 Rottalsattel and could speak to Bill Putnam 1972 each other again, he had no idea that anything untoward had happened. Stephanie Roberts 2011 I recall long journeys by car enlivened by his wide-ranging taste in music. Les Swindin 1979 The keynote of many outings was his sense of fun. There were long stories, John Tyson 1952 jokes or pithy one-liners. -

Complete 230 Fellranger Tick List A

THE LAKE DISTRICT FELLS – PAGE 1 A-F CICERONE Fell name Height Volume Date completed Fell name Height Volume Date completed Allen Crags 784m/2572ft Borrowdale Brock Crags 561m/1841ft Mardale and the Far East Angletarn Pikes 567m/1860ft Mardale and the Far East Broom Fell 511m/1676ft Keswick and the North Ard Crags 581m/1906ft Buttermere Buckbarrow (Corney Fell) 549m/1801ft Coniston Armboth Fell 479m/1572ft Borrowdale Buckbarrow (Wast Water) 430m/1411ft Wasdale Arnison Crag 434m/1424ft Patterdale Calf Crag 537m/1762ft Langdale Arthur’s Pike 533m/1749ft Mardale and the Far East Carl Side 746m/2448ft Keswick and the North Bakestall 673m/2208ft Keswick and the North Carrock Fell 662m/2172ft Keswick and the North Bannerdale Crags 683m/2241ft Keswick and the North Castle Crag 290m/951ft Borrowdale Barf 468m/1535ft Keswick and the North Catbells 451m/1480ft Borrowdale Barrow 456m/1496ft Buttermere Catstycam 890m/2920ft Patterdale Base Brown 646m/2119ft Borrowdale Caudale Moor 764m/2507ft Mardale and the Far East Beda Fell 509m/1670ft Mardale and the Far East Causey Pike 637m/2090ft Buttermere Bell Crags 558m/1831ft Borrowdale Caw 529m/1736ft Coniston Binsey 447m/1467ft Keswick and the North Caw Fell 697m/2287ft Wasdale Birkhouse Moor 718m/2356ft Patterdale Clough Head 726m/2386ft Patterdale Birks 622m/2241ft Patterdale Cold Pike 701m/2300ft Langdale Black Combe 600m/1969ft Coniston Coniston Old Man 803m/2635ft Coniston Black Fell 323m/1060ft Coniston Crag Fell 523m/1716ft Wasdale Blake Fell 573m/1880ft Buttermere Crag Hill 839m/2753ft Buttermere -

So You Want to Be an Expat

University of Nevada, Reno So You Want to be an Expat A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in English by Jennifer Weisberg Dr. Christopher Coake/Thesis Advisor May, 2009 THE GRADUATE SCHOOL We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by JENNIFER WEISBERG entitled So You Want To Be An Expat be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Christopher Coake, Advisor Gailmarie Pahmeier, Committee Member Gary Hausladen, Graduate School Representative Marsha H. Read, Ph. D., Associate Dean, Graduate School May, 2009 i Abstract A tongue-in-cheek memoir of an American family’s three year life in Zurich, Switzerland from 2000-2003. This memoir—written in the present tense and from a second-person point of view—explores themes of displacement, child-rearing, and personal identity from the perspective of a mother in her early thirties. 1 So You Want to be an Expat 1. And You’re Off You fly out of Denver on July 1st , 2000, with eight suitcases and a sense of adventure. You can count to ten in German, and you’ll pick up the rest when you get to Switzerland. It’s silly to entertain stereotypes, yet you envision felt-hatted yodelers calling to one another across edelweiss-cloaked meadows, the Swiss Miss girl perched on a snow-capped alp with her cup of cocoa, the echoing cry of Ricola! as mountaineers soothe their throats on herbal cough drops. Strong cheese, dark chocolate, and buttery pastries are a few of your favorite things, and they are waiting for you in Zurich, where you’ll spend the next three years. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Mountaineering Books Under £10

Mountaineering Books Under £10 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER EDITION CONDITION DESCRIPTION REFNo PRICE AA Publishing Focus On The Peak District AA Publishing 1997 First Edition 96pp, paperback, VG Includes walk and cycle rides. 49344 £3 Abell Ed My Father's Keep. A Journey Of Ed Abell 2013 First Edition 106pp, paperback, Fine copy The book is a story of hope for 67412 £9 Forgiveness Through The Himalaya. healing of our most complicated family relationships through understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, peace for ourselves despite our inability to save our loved ones from the ravages of addiction, and strength for the arduous yet enriching journey. Abraham Guide To Keswick & The Vale Of G.P. Abraham Ltd 20 page booklet 5890 £8 George D. Derwentwater Abraham Modern Mountaineering Methuen & Co 1948 3rd Edition 198pp, large bump to head of spine, Classic text from the rock climbing 5759 £6 George D. Revised slight slant to spine, Good in Good+ pioneer, covering the Alps, North dw. Wales and The Lake District. Abt Julius Allgau Landshaft Und Menschen Bergverlag Rudolf 1938 First Edition 143pp, inscription, text in German, VG- 10397 £4 Rother in G chipped dw. Aflalo F.G. Behind The Ranges. Parentheses Of Martin Secker 1911 First Edition 284pp, 14 illusts, original green cloth, Aflalo's wide variety of travel 10382 £8 Travel. boards are slightly soiled and marked, experiences. worn spot on spine, G+. Ahluwalia Major Higher Than Everest. Memoirs of a Vikas Publishing 1973 First Edition 188pp, Fair in Fair dw. Autobiography of one of the world's 5743 £9 H.P.S. Mountaineer House most famous mountaineers. -

View from the Summit Over the Italian Side of Mont Blanc Is Breathtaking! Descent Via Normal Route

Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix 190 place de l’église - 74400 Chamonix – France - Tél : + 33 (0)4 50 53 00 88 www.chamonix-guides.com - e-mail : [email protected] AIGUILLE VERTE - PRIVE - TISON Duration: 5 days Level: Price from: 2 485 € The Chamonix Compagnie des Guides offers you a collection of programmes to climb the legendary peaks of the Alps. We have selected a route together with a specific preparatory package for each peak. Each route chosen is universally recognised as unmissable. Thanks to our unique centre of expertise, we can also guide you on other routes. So don’t hesitate to dream big, as our expertise is at your service to help you make your dreams come true. The Aiguille Verte is THE legendary peak in the Mont Blanc Massif. The celebrated mountaineer and writer Gaston Rébuffat contributed significantly to this reputation when he said of it: “Before the Verte one is a mountaineer, on the Verte one becomes a ‘Montagnard’ (mountain dweller)”. It is certainly true that there are no easy routes on this peak and each face is a significant challenge. The south side of the Aiguille Verte is an outstanding snow route that follows the Whymper Couloir for over 700 metres. This is unquestionably one of the most beautiful routes in the massif, and we offer a four-day programme for its ascent. ITINERARY Day 1 and Day 2 : Acclimatisation routes with a night in the Torino Hut (3370m) These first two days give your body the essential time it requires to adapt to altitude. -

Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6

1 Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 1 <p> Chapter 2<p> Chapter 3 <p> Chapter 4 <p> Chapter 5 <p> Chapter 6 <p> Chapter 7 <p> Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. Jo's Boys 2 Chapter 8 <p> Chapter 9 <p> Chapter 10 <p> Chapter 11 <p> Chapter 12 <p> Chapter 13 <p> Chapter 14 <p> Chapter 15 <p> Chapter 16 <p> Chapter 17 <p> Chapter 18 <p> Chapter 19 <p> Chapter 20 <p> Chapter 21 <p> Chapter 22 <p> Jo's Boys *The Project Gutenberg Etext of Jo's Boys, by Louisa May Alcott* #8 in our series by Louisa M. Alcott Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the laws for your country before redistributing these files!!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Please do not remove this. This should be the first thing seen when anyone opens the book. Do not change or edit it without written permission. The words are carefully chosen to provide users with the information they need about what they can legally do with the texts. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These Etexts Are Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below, including for donations. -

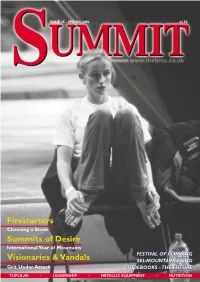

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

RR 01 07 Lake District Report.Qxp

A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas Integrated Geoscience Surveys (North) Programme Research Report RR/01/07 NAVIGATION HOW TO NAVIGATE THIS DOCUMENT Bookmarks The main elements of the table of contents are bookmarked enabling direct links to be followed to the principal section headings and sub-headings, figures, plates and tables irrespective of which part of the document the user is viewing. In addition, the report contains links: from the principal section and subsection headings back to the contents page, from each reference to a figure, plate or table directly to the corresponding figure, plate or table, from each figure, plate or table caption to the first place that figure, plate or table is mentioned in the text and from each page number back to the contents page. RETURN TO CONTENTS PAGE BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY RESEARCH REPORT RR/01/07 A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake The National Grid and other Ordnance Survey data are used with the permission of the District and adjacent areas Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. Licence No: 100017897/2004. D Millward Keywords Lake District, Lower Palaeozoic, Ordovician, Devonian, volcanic geology, intrusive rocks Front cover View over the Scafell Caldera. BGS Photo D4011. Bibliographical reference MILLWARD, D. 2004. A stratigraphical framework for the upper Ordovician and Lower Devonian volcanic and intrusive rocks in the English Lake District and adjacent areas. British Geological Survey Research Report RR/01/07 54pp.