APR 2017-07 Winter Cover FA.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Submission to the Senate Inquiry Into Manus Island and Nauru

Submission to the Inquiry into Serious allegations of abuse, self-harm and neglect of asylum seekers in relation to the Nauru Regional Processing Centre, and any like allegations in relation to the Manus Regional Processing Centre November 2016 Table of Contents Who we are ................................................................................................................................................. 2 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Australian context ....................................................................................................................................... 4 Government policy ...................................................................................................................................... 4 The Australian Government and private contractors: Outsourcing our obligations .................................. 5 Legal and moral implications ....................................................................................................................... 7 Looking ahead.............................................................................................................................................. 8 Our Recommendations ................................................................................................................................ 9 References ................................................................................................................................................ -

191-Greg-Donnelly.Pdf

LE G I S LA TI V E A S S EM B LY FO R TH E AU S TR A LI A N CA PI TA L TER RI TO R Y SELECT COMMITTEE ON END OF LIFE CHOICES IN THE ACT Ms Bec Cody MLA (Chair), Mrs Vicki Dunne MLA (Deputy Chair) , Ms Tara Cheyne MLA, Mrs Elizabeth Kikkert MLA, Ms Caroline Le Couteur MLA. Submission Cover Sheet End of Life Choices in the ACT Submission Number : 191 Date Authorised for Publication : 29/3/18 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL The Honourable Greg Donnelly MLC 9th March 2018 Committee Secretary Select Committee on End of Life Choices in the ACT Legislative Assembly for the ACT GPO Box 1020 CANBERRA ACT 2601 Dear Committee Secretary, RE: Inquiry into End of Life Choices in the ACT My name is Greg Donnelly and I am a member of the New South Wales Legislative Council. As the Committee may be aware, late last year the New South Wales Legislative Council debated a bill that provided for physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia. The bill was entitled the Voluntary Assisted Dying Bill 2017. The following link will take you to the webpage relating to the bill https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/bills/Pages/bill-detai1s.aspx?pk=3422. The bill was debated, voted on and defeated. As you would expect both MLCs and MLAs received a significant number of submissions and letters from organisations and constituents expressing serious concerns regarding the proposed legislation and calling on both Houses to unanimously oppose the bill. With respect to the submissions and letters, they dealt with both the broader concerns relating to physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia legislation as well as particular deficiencies and shortcomings regarding the bill that was before the Parliament. -

Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1

Tuesday, 15 October 2019 Legislative Council- PROOF Page 1 LEGISLATIVE COUNCIL Tuesday, 15 October 2019 The PRESIDENT (The Hon. John George Ajaka) took the chair at 14:30. The PRESIDENT read the prayers and acknowledged the Gadigal clan of the Eora nation and its elders and thanked them for their custodianship of this land. Governor ADMINISTRATION OF THE GOVERNMENT The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of a message regarding the administration of the Government. Bills ABORTION LAW REFORM BILL 2019 Assent The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of message from the Governor notifying Her Excellency's assent to the bill. REPRODUCTIVE HEALTH CARE REFORM BILL 2019 Protest The PRESIDENT: I report receipt of the following communication from the Official Secretary to the Governor of New South Wales: GOVERNMENT HOUSE SYDNEY Wednesday, 2 October, 2019 The Clerk of the Parliaments Dear Mr Blunt, I write at Her Excellency's command, to acknowledge receipt of the Protest made on 26 September 2019, under Standing Order 161 of the Legislative Council, against the Bill introduced as the "Reproductive Health Care Reform Bill 2019" that was amended so as to change the title to the "Abortion Law Reform Bill 2019'" by the following honourable members of the Legislative Council, namely: The Hon. Rodney Roberts, MLC The Hon. Mark Banasiak, MLC The Hon. Louis Amato, MLC The Hon. Courtney Houssos, MLC The Hon. Gregory Donnelly, MLC The Hon. Reverend Frederick Nile, MLC The Hon. Shaoquett Moselmane, MLC The Hon. Robert Borsak, MLC The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox, MLC The Hon. Mark Latham, MLC I advise that Her Excellency the Governor notes the protest by the honourable members. -

From Words to Action

Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People From Words To Action Fulfilling the obligation to be child safe Report No. 5 August 2020 Parliament of Western Australia Committee Members Chair Hon Dr S.E. Talbot, MLC Member for South West Region Deputy Chair Mr K.M. O'Donnell, MLA Member for Kalgoorlie Members Hon D.E.M. Faragher, MLC Member for East Metropolitan Region Mrs J.M.C. Stojkovski, MLA Member for Kingsley Committee Staff Principal Research Officer Ms Renee Gould Research Officer Ms Michele Chiasson Legislative Assembly Tel: (08) 9222 7494 Parliament House Fax: (08) 9222 7804 Harvest Terrace Email: [email protected] PERTH WA 6000 Website: www.parliament.wa.gov.au Published by the Parliament of Western Australia, Perth. August 2020. ISBN: 978-1-925724-61-5 (Series: Western Australia. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committees. Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People. Report 5) 328.365 Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People From Words To Action Fulfilling the obligation to be child safe Report No. 5 Presented by Hon Dr S.E. Talbot, MLC & Mr K.M. O'Donnell, MLA Laid on the Table of the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council on 13 August 2020 Inquiry Terms of Reference The Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People will examine the scope and direction of the work currently being undertaken by government agencies, regulatory bodies and non-government organisations to improve the monitoring of child safe standards and the role of the Commissioner for Children and Young People in ensuring Western Australia’s independent oversight mechanisms operate in a way that makes the interests of children and young people the paramount consideration. -

BBC TV\S Panorama, Conflict Coverage and the Μwestminster

%%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and WKHµ:HVWPLQVWHU FRQVHQVXV¶ David McQueen This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and due acknowledgement must always be made of the use of any material contained in, or derived from, this thesis. %%&79¶VPanorama, conflict coverage and the µ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen A thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements of Bournemouth University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2010 µLet nation speak peace unto nation¶ RIILFLDO%%&PRWWRXQWLO) µQuaecunque¶>:KDWVRHYHU@(official BBC motto from 1934) 2 Abstract %%&79¶VPanoramaFRQIOLFWFRYHUDJHDQGWKHµ:HVWPLQVWHUFRQVHQVXV¶ David Adrian McQueen 7KH%%&¶VµIODJVKLS¶FXUUHQWDIIDLUVVHULHVPanorama, occupies a central place in %ULWDLQ¶VWHOHYLVLRQKLVWRU\DQG\HWVXUSULVLQJO\LWLVUHODWLYHO\QHJOHFWHGLQDFDGHPLF studies of the medium. Much that has been written focuses on Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRI armed conflicts (notably Suez, Northern Ireland and the Falklands) and deals, primarily, with programmes which met with Government disapproval and censure. However, little has been written on Panorama¶VOHVVFRQWURYHUVLDOPRUHURXWLQHZDUUeporting, or on WKHSURJUDPPH¶VPRUHUHFHQWKLVWRU\LWVHYROYLQJMRXUQDOLVWLFSUDFWLFHVDQGSODFHZLWKLQ the current affairs form. This thesis explores these areas and examines the framing of war narratives within Panorama¶VFRYHUDJHRIWKH*XOIFRQIOLFWV of 1991 and 2003. One accusation in studies looking beyond Panorama¶VPRUHFRQWHQWLRXVHSLVRGHVLVWKDW -

Island of Despair

EMBARGOED COPY ISLAND OF DESPAIR AUSTRALIA’S “PROCESSING” OF REFUGEES ON NAURU Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 7 million people who campaign for a world where human rights are enjoyed by all. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. © Amnesty International 2016 Except where otherwise noted, content in this document is licensed under a Creative Commons (attribution, non-commercial, no derivatives, Cover photo: An Iranian refugee sits in an abandoned phosphate mine on Nauru international 4.0) licence. © Rémi Chauvin https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode For more information please visit the permissions page on our website: www.amnesty.org Where material is attributed to a copyright owner other than Amnesty International this material is not subject to the Creative Commons licence. First published in 2016 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House, 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW, UK Index: ASA 12/4934/2016 Original language: English amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1.1 Methodology 8 1.2 Terminology 9 2. BACKGROUND 11 2.1 Government of Australia’s policies towards people seeking protection 11 2.2 Nauru 12 2.3 Offshore “processing” of refugees 14 2.4 Legal standards 16 3. DRIVEN TO THE BRINK 19 3.1 Suicide and self-harm 19 3.2 Trapped in limbo 22 3.3 Inadequate medical care 24 3.4 Violations of children’s rights 29 4. -

2019 Nsw State Budget Estimates – Relevant Committee Members

2019 NSW STATE BUDGET ESTIMATES – RELEVANT COMMITTEE MEMBERS There are seven “portfolio” committees who run the budget estimate questioning process. These committees correspond to various specific Ministries and portfolio areas, so there may be a range of Ministers, Secretaries, Deputy Secretaries and senior public servants from several Departments and Authorities who will appear before each committee. The different parties divide up responsibility for portfolio areas in different ways, so some minor party MPs sit on several committees, and the major parties may have MPs with titles that don’t correspond exactly. We have omitted the names of the Liberal and National members of these committees, as the Alliance is seeking to work with the Opposition and cross bench (non-government) MPs for Budget Estimates. Government MPs are less likely to ask questions that have embarrassing answers. Victor Dominello [Lib, Ryde], Minister for Customer Services (!) is the minister responsible for Liquor and Gaming. Kevin Anderson [Nat, Tamworth], Minister for Better Regulation, which is located in the super- ministry group of Customer Services, is responsible for Racing. Sophie Cotsis [ALP, Canterbury] is the Shadow for Better Public Services, including Gambling, Julia Finn [ALP, Granville] is the Shadow for Consumer Protection including Racing (!). Portfolio Committee no. 6 is the relevant committee. Additional information is listed beside each MP. Bear in mind, depending on the sitting timetable (committees will be working in parallel), some MPs will substitute in for each other – an MP who is not on the standing committee but who may have a great deal of knowledge might take over questioning for a session. -

Terrorist Speech and the Future of Free Expression

TERRORIST SPEECH AND THE FUTURE OF FREE EXPRESSION Laura K. Donohue* Introduction.......................................................................................... 234 I. State as Sovereign in Relation to Terrorist Speech ...................... 239 A. Persuasive Speech ............................................................ 239 1. Sedition and Incitement in the American Context ..... 239 a. Life Before Brandenburg................................. 240 b. Brandenburg and Beyond................................ 248 2. United Kingdom: Offences Against the State and Public Order ....................................................................... 250 a. Treason............................................................. 251 b. Unlawful Assembly ......................................... 254 c. Sedition ............................................................ 262 d. Monuments and Flags...................................... 268 B. Knowledge-Based Speech ................................................ 271 1. Prior Restraint in the American Context .................... 272 a. Invention Secrecy Act...................................... 274 b. Atomic Energy Act .......................................... 279 c. Information Relating to Explosives and Weapons of Mass Destruction............................................ 280 2. Strictures in the United Kingdom............................... 287 a. Informal Restrictions........................................ 287 b. Formal Strictures: The Export Control Act ..... 292 II. State in -

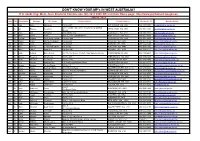

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

The Parliamentary Bypass Operation

The parliamentary bypass operation by Labour MP Robert Sheldon - reported to This is the story of a scandal. The government has failed to account to Parliament that they wished to 'reaffirm the Parliament for expenditure of half a billion pounds on a secret 'spy' satellite, importance' they attached to the statement 'as a due to be positioned over the Soviet Union. In doing so, it has flagrantly breached means of keeping Parliament reliably informed about the costs and progress of major Defence a solemn promise to inform Parliament, through its public Accounts Committee, projects' . of all major defence expenditure. This was to be the subject of the first At the time the agreement was made in 1982, Sheldon's predecessor as chair of the PAC, Lord programme in a forthcoming BBC2 series Secret Society, written and presented Barnett, wrote that 'full accountability to by New Statesman writer DUN CAN CAMPBELL. Last Thursday, BBC Parliament in future is imperative'. Yet within a year, the government was breaking that agreement director general Alasdair Milne banned the programme. Here, for the first time, by secretly developing Zircon. Campbell is able to tell the story of official deceit. (Additional research by Lord Barnett, ironically, is now the Deputy Chairman of the BBC. The man who made the Jolyon Jenkins and Patrick Forbes) agreement with Barnett was Sir Frank Cooper - then the Ministry of Defence Permanent PROJECT ZIRCON is the secret codename for Permanent Secretaries' Committee on the Secretary, but now a late convert to campaigning Britain's first ever spy satellite. Zircon, originally Intelligence Services (PSIS), and would have then for Freedom of Information and better planned to be launched in 1988, will be a 'signals been passed to the Prime Minister. -

EMAIL ADDRESS Postal Address for All Upper House Members

TITLE NAME EMAIL ADDRESS Phone Postal Address for all Upper House Members: Parliament House, 6 Macquarie St, Sydney NSW, 2000 Shooters, Fishers and Farmers Party The Hon. Robert Borsak [email protected] (02) 9230 2850 The Hon. Robert Brown [email protected] (02) 9230 3059 Liberal Party The Hon. John Ajaka [email protected] (02) 9230 2300 The Hon. Lou Amato [email protected] (02) 9230 2764 The Hon. David Clarke [email protected] (02) 9230 2260 The Hon. Catherine Cusack [email protected] (02) 9230 2915 The Hon. Scott Farlow [email protected] (02) 9230 3786 The Hon. Don Harwin [email protected] (02) 9230 2080 Mr Scot MacDonald [email protected] (02) 9230 2393 The Hon. Natasha Maclaren-Jones [email protected] (02) 9230 3727 The Hon. Shayne Mallard [email protected] (02) 9230 2434 The Hon. Taylor Martin [email protected] 02 9230 2985 The Hon. Matthew Mason-Cox [email protected] (02) 9230 3557 The Hon. Greg Pearce [email protected] (02) 9230 2328 The Hon. Dr Peter Phelps [email protected] (02) 9230 3462 National Party: The Hon. Niall Blair [email protected] (02) 9230 2467 The Hon. Richard Colless [email protected] (02) 9230 2397 The Hon. Wes Fang [email protected] (02) 9230 2888 The Hon. -

UK Eyes Alpha by the Same Author UK Eyes Alpha Big Boys' Rules: the SAS and the Secret Struggle Against the IRA Lnside British Lntelligence

UK Eyes Alpha By the same author UK Eyes Alpha Big Boys' Rules: The SAS and the secret struggle against the IRA lnside British lntelligence Mark Urban tr firhrr anr/ fulrr' ft For Ruth and Edwin Contents lntroduction Part One The First published in I996 1 Coming Earthquake 3 and Faber Limited by Faber 2 A Dark and Curious Shadow 13 3 Queen Square London vcrN JAU 3 The Charm Offensive 26 Typeset by Faber and Faber Ltd Printed in England by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc 4 Most Ridiculed Service 42 All rights reserved 5 ZIRCON 56 O Mark Urban, 1996 6 Springtime for Sceptics 70 Mark Urbar-r is hereby identified as author of 7 A Brilliant Intelligence Operation 84 this work in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 8 The \7all Comes Tumbling Down 101 A CIP rccord for this book is available from the Part Two British Library 9 Supergun LL7 tsnN o-57r-r7689-5 10 Black Death on the Nevsky Prospekt L29 ll Assault on Kuwait L43 12 Desert Shield 153 13 Desert Storm 165 14 Moscow Endgame LA2 Part Three l5 An Accidcnt of History L97 l(r Irrlo thc ll:rllirrn 2LO tt),)B / (,1,1 l, I Qulgrnirc 17 Time for Revenge 22L lntroduction 18 Intelligence, Power and Economic Hegemony 232 19 Very Huge Bills 245 How good is British intelligence? What kind of a return do ministers and officials get 20 The Axe Falls 2il for the hundreds of millions of pounds spent on espionage each year? How does this secret establishment find direction and purpose 2l Irish Intrigues 269 in an age when old certainties have evaporated? Very few people, even in Conclusion 286 Whitehall, would feel confident enough to answer these questions.