Ms Rita Saffioti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mr Peter Katsambanis; Dr David Honey; Mr Peter Rundle; Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Dean Nalder; Mr Zak Kirkup

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 16 April 2020] p2273b-2298a Mr John Quigley; Mr Peter Katsambanis; Dr David Honey; Mr Peter Rundle; Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Libby Mettam; Mr Dean Nalder; Mr Zak Kirkup COMMERCIAL TENANCIES (COVID-19 RESPONSE) BILL 2020 Introduction and First Reading Bill introduced, on motion by Mr J.R. Quigley (Minister for Commerce), and read a first time. Explanatory memorandum presented by the minister. Second Reading MR J.R. QUIGLEY (Butler — Minister for Commerce) [6.52 pm]: I move — That the bill be now read a second time. The bill I am introducing today is essential to support the continuity of commercial tenancies, during what is likely to be a period of significant social and economic upheaval for all Western Australians. The social and economic health and wellbeing of Western Australians is the government’s highest priority as we face the significant challenges presented to us by the spread of COVID-19. On 29 March 2020, the national cabinet announced that a moratorium on evictions for non-payment of rent would be applied across commercial tenancies impacted by financial distress due to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. On 3 April 2020, the national cabinet announced a set of common principles to provide protections and relief for tenants in relation to commercial tenancies, and on 7 April 2020, it endorsed the mandatory code of conduct, the National Cabinet Mandatory Code of Conduct for SME Commercial Leasing Principles during COVID-19, aimed at mitigating and limiting the hardship suffered by the community as a result of the spread of COVID-19 in our state and across the nation. -

P982c-988A Dr David Honey; Mrs Michelle Roberts; Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Shane Love

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 20 February 2020] p982c-988a Dr David Honey; Mrs Michelle Roberts; Mrs Liza Harvey; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Shane Love MINISTER FOR TRANSPORT — ALLEGATIONS AGAINST MEMBER FOR RIVERTON Standing Orders Suspension — Motion DR D.J. HONEY (Cottesloe) [4.27 pm]: — without notice: I move — That so much of standing orders be suspended as is necessary to enable the following motion to be moved forthwith — That this house requires the Minister for Transport to table evidence of an allegation of bullying and intimidation by the member for Riverton toward the Mayor of Nedlands, given that he did not speak to the mayor at the event in question; and, if she cannot, the house will require her to immediately apologise for defaming the member for Riverton and misleading the Parliament of Western Australia. I understand that the acting Leader of the House has agreed to this and has agreed on times for the motion. Standing Orders Suspension — Amendment to Motion MRS M.H. ROBERTS (Midland — Minister for Police) [4.27 pm]: Although I do not believe that there is any substance to the motion, we are prepared to hear what the opposition has to say. I move — To insert after “forthwith” — , subject to the debate being limited to 10 minutes for government members and 10 minutes for non-government members Amendment put and passed. Standing Orders Suspension — Motion, as Amended The ACTING SPEAKER (Mr T.J. Healy): As this is a motion without notice to suspend standing orders, it will need an absolute majority in order to succeed. -

P4007b-4019A Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Bill Johnston; Mr Chris Tallentire

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 17 June 2014] p4007b-4019a Dr Mike Nahan; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Bill Johnston; Mr Chris Tallentire APPROPRIATION (CONSOLIDATED ACCOUNT) CAPITAL 2014–15 BILL 2014 Third Reading DR M.D. NAHAN (Riverton — Treasurer) [8.50 pm]: I move — That the bill be now read a third time. MS R. SAFFIOTI (West Swan) [8.50 pm]: It is a pleasure to be on my feet once again today, this time dealing with the Appropriation (Consolidated Account) Capital 2014–15 Bill 2014. In my earlier speech today I outlined some of the structural problems with the recurrent operating side of the budget. I want to talk briefly about the capital side of the budget and one of the reasons that net debt is increasing. As I have stated before, we all support capital expenditure because it provides much-needed infrastructure throughout our community. What is really good for capital infrastructure is to not have to borrow for the whole lot of it, and that is one of the reasons net debt has increased dramatically under this government. The opposition supports capital investment and public sector infrastructure, but the government has had to borrow for basically everything it is building. I reflect upon the discussions about funding the Perth–Mandurah railway in the early 2000s. I remember the criticism of the Liberal Party at the time that it was unaffordable. I read comments the other night that said that it was five or 10 years before its time. Mr D.J. Kelly: Trains before their time! Ms R. -

Reports to Be Received

OFFICE OF THE CEO REPORTS TO BE RECEIVED CEO067 – WALGA State Council Agenda – 1 July 2020 23 June 2020 State Council Agenda 1 July 2020 State Council Agenda NOTICE OF MEETING Meeting of the Western Australian Local Government Association State Council to be held at the City of Stirling, 25 Cedric Street Stirling, on Wednesday 1 July commencing at 4pm. 1. ATTENDANCE, APOLOGIES & ANNOUNCEMENTS 1.1 Attendance Members President of WALGA - Chair Mayor Tracey Roberts JP Deputy President of WALGA, Northern Country President Cr Karen Chappel JP Zone Avon-Midland Country Zone President Cr Ken Seymour Central Country Zone President Cr Phillip Blight Central Metropolitan Zone Cr Jenna Ledgerwood Central Metropolitan Zone Cr Paul Kelly East Metropolitan Zone Cr Catherine Ehrhardt East Metropolitan Zone Cr Cate McCullough Goldfields Esperance Country Zone President Cr Malcolm Cullen Gascoyne Country Zone President Cr Cheryl Cowell Great Eastern Country Zone President Cr Stephen Strange Great Southern Country Zone Cr Ronnie Fleay Kimberley Country Zone Cr Chris Mitchell JP Murchison Country Zone Cr Les Price North Metropolitan Zone Cr Frank Cvitan North Metropolitan Zone Mayor Mark Irwin North Metropolitan Zone Cr Russ Fishwick JP Peel Country Zone President Cr Michelle Rich Pilbara Country Zone Mayor Peter Long South East Metropolitan Zone Cr Julie Brown South East Metropolitan Zone Mayor Ruth Butterfield South Metropolitan Zone Cr Doug Thompson South Metropolitan Zone Mayor Carol Adams OAM South Metropolitan Zone Mayor Logan Howlett JP South West -

P336a-352A Mr Mark Mcgowan; Mr Ben Wyatt; Mr Sean L'estrange; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Frank Alban; Mr Bill Johnston

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 17 February 2016] p336a-352a Mr Mark McGowan; Mr Ben Wyatt; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Ms Rita Saffioti; Mr Frank Alban; Mr Bill Johnston PREMIER’S STATEMENT Consideration Resumed from 16 February on the following question — That the Premier’s Statement be noted. MR M. McGOWAN (Rockingham — Leader of the Opposition) [12.20 pm]: I rise to speak on the Premier’s Statement. The year 2016 marks the final year before the state election. It is a crucial year for Western Australia. Western Australia is at the crossroads. Our state needs change; it needs a change of direction and Western Australians know it. Western Australia is crying out for a change from the management that this government has provided this state. Our state needs a new government. It needs new ideas and it needs a new direction. We need to get rid of our tired, old government—a government that has created an enormous mess in Western Australia. We need a competent, responsible and honest government in Western Australia. We need a government with a vision for the future—the long-term future of Western Australia—and a team that is prepared to hang in there for the long haul. WA Labor has a team that is ready to govern. I love this state. It has provided me with opportunities beyond my wildest imaginings. I may have come from somewhere else, but I have lived the majority of my life in Western Australia. This is a state of resilient, decent and hardworking people with good values of honesty, compassion and decency. -

From Words to Action

Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People From Words To Action Fulfilling the obligation to be child safe Report No. 5 August 2020 Parliament of Western Australia Committee Members Chair Hon Dr S.E. Talbot, MLC Member for South West Region Deputy Chair Mr K.M. O'Donnell, MLA Member for Kalgoorlie Members Hon D.E.M. Faragher, MLC Member for East Metropolitan Region Mrs J.M.C. Stojkovski, MLA Member for Kingsley Committee Staff Principal Research Officer Ms Renee Gould Research Officer Ms Michele Chiasson Legislative Assembly Tel: (08) 9222 7494 Parliament House Fax: (08) 9222 7804 Harvest Terrace Email: [email protected] PERTH WA 6000 Website: www.parliament.wa.gov.au Published by the Parliament of Western Australia, Perth. August 2020. ISBN: 978-1-925724-61-5 (Series: Western Australia. Parliament. Legislative Assembly. Committees. Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People. Report 5) 328.365 Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People From Words To Action Fulfilling the obligation to be child safe Report No. 5 Presented by Hon Dr S.E. Talbot, MLC & Mr K.M. O'Donnell, MLA Laid on the Table of the Legislative Assembly and Legislative Council on 13 August 2020 Inquiry Terms of Reference The Joint Standing Committee on the Commissioner for Children and Young People will examine the scope and direction of the work currently being undertaken by government agencies, regulatory bodies and non-government organisations to improve the monitoring of child safe standards and the role of the Commissioner for Children and Young People in ensuring Western Australia’s independent oversight mechanisms operate in a way that makes the interests of children and young people the paramount consideration. -

Parliamentary Handbook the Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Twenty-Fourth Edition Twenty-Fourth Edition

The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Parliamentary Australian Western The The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook Twenty-Fourth Edition Twenty-Fourth Twenty-Fourth Edition David Black The Western Australian PARLIAMENTARY HANDBOOK TWENTY-FOURTH EDITION DAVID BLACK (editor) www.parliament.wa.gov.au Parliament of Western Australia First edition 1922 Second edition 1927 Third edition 1937 Fourth edition 1944 Fifth edition 1947 Sixth edition 1950 Seventh edition 1953 Eighth edition 1956 Ninth edition 1959 Tenth edition 1963 Eleventh edition 1965 Twelfth edition 1968 Thirteenth edition 1971 Fourteenth edition 1974 Fifteenth edition 1977 Sixteenth edition 1980 Seventeenth edition 1984 Centenary edition (Revised) 1990 Supplement to the Centenary Edition 1994 Nineteenth edition (Revised) 1998 Twentieth edition (Revised) 2002 Twenty-first edition (Revised) 2005 Twenty-second edition (Revised) 2009 Twenty-third edition (Revised) 2013 Twenty-fourth edition (Revised) 2018 ISBN - 978-1-925724-15-8 The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook The 24th Edition iv The Western Australian Parliamentary Handbook The 24th Edition PREFACE As an integral part of the Western Australian parliamentary history collection, the 24th edition of the Parliamentary Handbook is impressive in its level of detail and easy reference for anyone interested in the Parliament of Western Australia and the development of parliamentary democracy in this State since 1832. The first edition of the Parliamentary Handbook was published in 1922 and together the succeeding volumes represent one of the best historical record of any Parliament in Australia. In this edition a significant restructure of the Handbook has taken place in an effort to improve usability for the reader. The staff of both Houses of Parliament have done an enormous amount of work to restructure this volume for easier reference which has resulted in a more accurate, reliable and internally consistent body of work. -

Western Australian Government Cabinet Ministers

Honourable Mark McGOWAN BA LLB MLA Western Australian Government Premier; Treasurer; Minister for Public Sector Management; Federal-State Relations 13th Floor, Dumas House Cabinet Ministers 2 Havelock Street WEST PERTH WA 6005 6552 5000 6552 5001 [email protected] Honourable Roger H COOK Honourable Sue M ELLERY Honourable Stephen N DAWSON Honourable Alannah MacTIERNAN BA GradDipBus (PR) MBA MLA BA MLC MLC MLC Deputy Premier; Minister for Health; Minister for Education and Training Minister for Mental Health; Aboriginal Minister for Regional Development; Medical Research; State Development, Affairs; Industrial Relations Agriculture and Food; Hydrogen 12th Floor, Dumas House Jobs and Trade; Science Industry 2 Havelock Street, 12th Floor, Dumas House 13th Floor, Dumas House WEST PERTH WA 6005 2 Havelock Street, 11th Floor, Dumas House 2 Havelock Street, WEST PERTH WA 6005 2 Havelock Street, WEST PERTH WA 6005 6552 5700 WEST PERTH WA 6005 6552 5701 6552 5800 6552 6500 [email protected] 6552 5801 6552 6200 6552 6501 [email protected] 6552 6201 [email protected] [email protected] Honourable David A TEMPLEMAN Honourable John R QUIGLEY Honourable Paul PAPALIA Honourable Bill J JOHNSTON Dip Tchg BEd MLA LLB JP MLA CSC MLA MLA Minister for Tourism; Culture and the Attorney General; Minister for Minister for Police; Road Safety; Defence Minister for Mines and Petroleum; Arts; Heritage Electoral Affairs Industry; Veterans Issues Energy; Corrective Services 10th Floor, Dumas House 11th Floor, -

![Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 17 February 2011] P641b](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9893/extract-from-hansard-assembly-thursday-17-february-2011-p641b-719893.webp)

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 17 February 2011] P641b

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Thursday, 17 February 2011] p641b-673a Mr John Quigley; Mrs Michelle Roberts; Mr Peter Tinley; Mr Eric Ripper; Mr Fran Logan; Mr Murray Cowper; Mr Ben Wyatt; Mr Peter Watson; Ms Adele Carles; Mr Mick Murray PREMIER’S STATEMENT Consideration Resumed from 16 February on the following question — That the Premier’s Statement be noted. MR J.R. QUIGLEY (Mindarie) [9.31 am]: Mr Speaker, I would like to make a speech concerning policing in Western Australia. At the outset, I preface my speech by saying that I have the utmost respect and admiration for the thousands of brave and conscientious police officers who police Western Australia, and who, by their devotion to duty, secure the streets so that they are safe enough for my wife and my children to walk about without the expectation of being assaulted or otherwise endangered. I thank all those officers who serve in the traffic branch and who stay up all night in difficult conditions, patrolling our streets to keep the streets safe enough for me to drive home with the expectation that I will not be killed by a hoon. I thank all of those officers serving in crime command who work so valiantly detecting crime by organised criminals and others, and who have achieved such remarkable results, especially in the interdiction of drug laboratories. They have made big inroads into the amphetamine trade in Western Australia. Finally, I thank, also, those officers of this state, including the undercover officers, who on a daily basis put themselves in danger by engaging with organised criminals and bikie gangs to bring evidence before the courts that will see these people prosecuted. -

Ms Margaret Quirk; Mr David Templeman; Mr Peter Watson; Mr Chris Tallentire

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 25 June 2014] p4599b-4611a Mr Mark McGowan; Ms Margaret Quirk; Mr David Templeman; Mr Peter Watson; Mr Chris Tallentire SENIORS — COST-OF-LIVING INCREASES — CONCESSION FUNDING Motion MR M. McGOWAN (Rockingham — Leader of the Opposition) [4.31 pm]: I move — That the house condemns the state Liberal–National government and the federal Liberal government for making the lives of seniors and pensioners increasingly difficult through increased cost of living and the withdrawal of concessions. The way that both state and federal Liberal governments are treating seniors in our community has become a subject of great debate in Western Australia and Australia more generally in recent weeks. We have heard some unfortunate commentary by some government ministers who imply that seniors are somehow living it up, are on easy street and are being treated overgenerously by the government. We heard the Minister for Transport make some insensitive remarks. The Minister for Seniors and Volunteering made some fairly insensitive remarks about seniors in our community. This has upset seniors across Western Australia. Last Friday I attended a rally at Perth Town Hall, which was organised by 6PR and Channel Seven and the Council on the Ageing. This was a significant event; the many hundreds of people present at this rally last Friday are concerned about the attacks on their living standards by both state and federal governments. They raised a range of concerns about what is happening nationally and what is consequently happening at a state level that is impacting on their quality of life and their capacity to afford to live. -

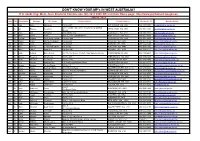

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

P1226b-1231A Mr David Templeman; Ms Margaret Quirk; Mr Sean L'estrange

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 16 March 2016] p1226b-1231a Mr David Templeman; Ms Margaret Quirk; Mr Sean L'Estrange SENTENCE ADMINISTRATION AMENDMENT BILL 2016 Second Reading Resumed from 24 February. MR D.A. TEMPLEMAN (Mandurah) [7.25 pm]: I would like to speak to the motion before us on the notice paper, which is a private members’ bill, the Sentence Administration Amendment Bill 2016, that was introduced by the member for Butler. The ACTING SPEAKER (Mr P. Abetz): There are too many conversations happening all at once. The member for Mandurah has the call, so let us take our conversations outside or hush our voices a little. Thank you. Mr D.A. TEMPLEMAN: Earlier this year members would be aware that I tabled a substantial online petition signed by over 20 000 online petitioners and a petition that complied with standing orders of this place that was signed by two members of the public—Margaret and Ray Dodd. Margaret and Ray’s daughter Hayley went missing a number of years ago and she has never been found, and, of course, it is presumed that she met a tragic end. I do not want to talk about their case because it is before the court and I do not want to prejudice or have any negative impact on the proper procedures in this case. Margaret and Ray are like a number of parents and families in not only Western Australia but Australia generally who have loved ones, daughters or sons, who have gone missing—some who were murdered but their perpetrator has never been found or indeed the perpetrator has been tried for murder and been found guilty.