From Words to Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

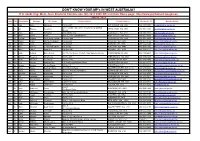

DON't KNOW YOUR MP's in WEST AUSTRALIA? If in Doubt Ring: West

DON'T KNOW YOUR MP's IN WEST AUSTRALIA? If in doubt ring: West. Aust. Electoral Commission (08) 9214 0400 OR visit their Home page: http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au HOUSE : MLA Hon. Title First Name Surname Electorate Postal address Postal Address Electorate Tel Member Email Ms Lisa Baker Maylands PO Box 907 INGLEWOOD WA 6932 (08) 9370 3550 [email protected] Unit 1 Druid's Hall, Corner of Durlacher & Sanford Mr Ian Blayney Geraldton GERALDTON WA 6530 (08) 9964 1640 [email protected] Streets Dr Tony Buti Armadale 2898 Albany Hwy KELMSCOTT WA 6111 (08) 9495 4877 [email protected] Mr John Carey Perth Suite 2, 448 Fitzgerald Street NORTH PERTH WA 6006 (08) 9227 8040 [email protected] Mr Vincent Catania North West Central PO Box 1000 CARNARVON WA 6701 (08) 9941 2999 [email protected] Mrs Robyn Clarke Murray-Wellington PO Box 668 PINJARRA WA 6208 (08) 9531 3155 [email protected] Hon Mr Roger Cook Kwinana PO Box 428 KWINANA WA 6966 (08) 6552 6500 [email protected] Hon Ms Mia Davies Central Wheatbelt PO Box 92 NORTHAM WA 6401 (08) 9041 1702 [email protected] Ms Josie Farrer Kimberley PO Box 1807 BROOME WA 6725 (08) 9192 3111 [email protected] Mr Mark Folkard Burns Beach Unit C6, Currambine Central, 1244 Marmion Avenue CURRAMBINE WA 6028 (08) 9305 4099 [email protected] Ms Janine Freeman Mirrabooka PO Box 669 MIRRABOOKA WA 6941 (08) 9345 2005 [email protected] Ms Emily Hamilton Joondalup PO Box 3478 JOONDALUP WA 6027 (08) 9300 3990 [email protected] Hon Mrs Liza Harvey Scarborough -

Ms Rita Saffioti

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Wednesday, 28 August 2019] p6048b-6082a Mrs Robyn Clarke; Mr Mick Murray; Ms Rita Saffioti; Ms Janine Freeman; Mr John Carey; Mr Ben Wyatt; Dr David Honey; Mr David Templeman; Mr Terry Healy; Mr Stephen Price; Ms Lisa Baker; Ms Simone McGurk; Mr Matthew Hughes; Mr Donald Punch; Mrs Jessica Stojkovski; Ms Sabine Winton VOLUNTARY ASSISTED DYING BILL 2019 Second Reading Resumed from an earlier stage of the sitting. MRS R.M.J. CLARKE (Murray–Wellington) [8.01 pm]: Prior to the dinner break, I was in the middle of my speech. On 23 August 2017, the Parliament established a joint select committee of the Legislative Assembly and the Legislative Council to inquire into and report on the need for laws in Western Australia to allow citizens to make informed decisions regarding their own end-of-life choices. The Joint Select Committee on End of Life Choices was formed. The terms of reference included — a) assess the practices currently being utilised within the medical community to assist a person to exercise their preferences for the way they want to manage their end of life when experiencing chronic and/or terminal illnesses, including the role of palliative care; b) review the current framework of legislation, proposed legislation and other relevant reports and materials in other Australian States and Territories and overseas jurisdictions; c) consider what type of legislative change may be required, including an examination of any federal laws that may impact such legislation; and d) examine the role of Advanced Health Directives, Enduring Power of Attorney and Enduring Power of Guardianship laws and the implications for individuals covered by these instruments in any proposed legislation. -

![[ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 28 November 2017] P6160b-6179A Mr](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6772/assembly-tuesday-28-november-2017-p6160b-6179a-mr-1566772.webp)

[ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 28 November 2017] P6160b-6179A Mr

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY — Tuesday, 28 November 2017] p6160b-6179a Mr John Quigley; Mr Sean L'Estrange; Dr Tony Buti; Dr Mike Nahan; Mr Simon Millman; Ms Cassandra Rowe; Mr Peter Rundle; Mrs Jessica Stojkovski; Mrs Lisa O'Malley; Mrs Liza Harvey; Mr Bill Johnston; Ms Mia Davies CIVIL LIABILITY LEGISLATION AMENDMENT (CHILD SEXUAL ABUSE ACTIONS) BILL 2017 Declaration as Urgent MR J.R. QUIGLEY (Butler — Attorney General) [4.09 pm]: In accordance with standing order 168(2), I move — That the bill be considered an urgent bill. Perhaps the opposition could indicate its consent for this motion. MR S.K. L’ESTRANGE (Churchlands) [4.09 pm]: Yes; we are happy to proceed to the second reading. Question put and passed. Second Reading Resumed from 22 November. DR A.D. BUTI (Armadale) [4.10 pm]: I stand to contribute to the second reading debate on the incredibly important Civil Liability Legislation Amendment (Child Sexual Abuse Actions) Bill 2017. When the Attorney General introduced this bill to the house last week, he stated — On behalf of the McGowan state Labor government and the people of Western Australia, it gives me great pleasure to introduce this bill that fulfils an election commitment to remove the limitation periods in respect of civil actions for child sexual abuse. As members will be aware, this is a historic bill. In some respects, the government’s legislation will go further than any similar legislation in any other Australian jurisdiction to date. Those words are very important. It is a very historic bill and, in some respects, it does go further than any other jurisdiction in Australia, which is quite interesting because until this bill is passed, Western Australia has arguably the most draconian Limitation Act in Australia. -

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon

M EMBER E LECTORATE C ONTACT DETAILS Hon. Peter Bruce Watson MLA PO Box 5844 Albany 6332 Ph: 9841 8799 Albany Speaker Email: [email protected] Party: ALP Dr Antonio (Tony) De 2898 Albany Highway Paulo Buti MLA Kelmscott WA 6111 Party: ALP Armadale Ph: (08) 9495 4877 Email: [email protected] Website: https://antoniobuti.com/ Mr David Robert Michael MLA Suite 3 36 Cedric Street Stirling WA 6021 Balcatta Government Whip Ph: (08) 9207 1538 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Reece Raymond Whitby MLA P.O. Box 4107 Baldivis WA 6171 Ph: (08) 9523 2921 Parliamentary Secretary to the Email: [email protected] Treasurer; Minister for Finance; Aboriginal Affairs; Lands, and Baldivis Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for Environment; Disability Services; Electoral Affairs Party: ALP Hon. David (Dave) 6 Old Perth Road Joseph Kelly MLA Bassendean WA 6054 Ph: 9279 9871 Minister for Water; Fisheries; Bassendean Email: [email protected] Forestry; Innovation and ICT; Science Party: ALP Mr Dean Cambell Nalder MLA P.O. Box 7084 Applecross North WA 6153 Ph: (08) 9316 1377 Shadow Treasurer ; Shadow Bateman Email: [email protected] Minister for Finance; Energy Party: LIB Ms Cassandra (Cassie) PO Box 268 Cloverdale 6985 Michelle Rowe MLA Belmont Ph: (08) 9277 6898 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mrs Lisa Margaret O'Malley MLA P.O. Box 272 Melville 6156 Party: ALP Bicton Ph: (08) 9316 0666 Email: [email protected] Mr Donald (Don) PO Box 528 Bunbury 6230 Thomas Punch MLA Bunbury Ph: (08) 9791 3636 Party: ALP Email: [email protected] Mr Mark James Folkard MLA Unit C6 Currambine Central Party: ALP 1244 Marmion Avenue Burns Beach Currambine WA 6028 Ph: (08) 9305 4099 Email: [email protected] Hon. -

APR 2017-07 Winter Cover FA.Indd

Printer to adjust spine as necessary Australasian Parliamentary Review Parliamentary Australasian Australasian Parliamentary Review JOURNAL OF THE AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP Editor Colleen Lewis Fifty Shades of Grey(hounds) AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 Federal and WA Elections Off Shore, Out of Reach? • VOL 32 NO 32 1 VOL AUTUMN/WINTER 2017 • VOL 32 NO 1 • RRP $A35 AUSTRALASIAN STUDY OF PARLIAMENT GROUP (ASPG) AND THE AUSTRALASIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW (APR) APR is the official journal of ASPG which was formed in 1978 for the purpose of encouraging and stimulating research, writing and teaching about parliamentary institutions in Australia, New Zealand and the South Pacific Membership of the Australasian Study of (see back page for Notes to Contributors to the journal and details of AGPS membership, which includes a subscription to APR). To know more about the ASPG, including its Executive membership and its Chapters, Parliament Group go to www.aspg.org.au Australasian Parliamentary Review Membership Editor: Dr Colleen Lewis, [email protected] The ASPG provides an outstanding opportunity to establish links with others in the parliamentary community. Membership includes: Editorial Board • Subscription to the ASPG Journal Australasian Parliamentary Review; Dr Peter Aimer, University of Auckland Dr Stephen Redenbach, Parliament of Victoria • Concessional rates for the ASPG Conference; and Jennifer Aldred, Public and Regulatory Policy Consultant Dr Paul Reynolds, Parliament of Queensland • Participation in local Chapter events. Dr David Clune, University of Sydney Kirsten Robinson, Parliament of Western Australia Dr Ken Coghill, Monash University Kevin Rozzoli, University of Sydney Rates for membership Prof. Brian Costar, Swinburne University of Technology Prof. -

Western Australia Ministry List 2021

Western Australia Ministry List 2021 Minister Portfolio Hon. Mark McGowan MLA Premier Treasurer Minister for Public Sector Management Minister for Federal-State Relations Hon. Roger Cook MLA Deputy Premier Minister for Health Minister for Medical Research Minister for State Development, Jobs and Trade Minister for Science Hon. Sue Ellery MLC Minister for Education and Training Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Stephen Dawson MLC Minister for Mental Health Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Minister for Industrial Relations Deputy Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Hon. Alannah MacTiernan MLC Minister for Regional Development Minister for Agriculture and Food Minister Assisting the Minister for State Development for Hydrogen Hon. David Templeman MLA Minister for Tourism Minister for Culture and the Arts Minister for Heritage Leader of the House Hon. John Quigley MLA Attorney General Minister for Electoral Affairs Minister Portfolio Hon. Paul Papalia MLA Minister for Police Minister for Road Safety Minister for Defence Industry Minister for Veterans’ Issues Hon. Bill Johnston MLA Minister for Mines and Petroleum Minister for Energy Minister for Corrective Services Hon. Rita Saffioti MLA Minister for Transport Minister for Planning Minister for Ports Hon. Dr Tony Buti MLA Minister for Finance Minister for Lands Minister for Sport and Recreation Minister for Citizenship and Multicultural Interests Hon. Simone McGurk MLA Minister for Child Protection Minister for Women’s Interests Minister for Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence Minister for Community Services Hon. Dave Kelly MLA Minister for Water Minister for Forestry Minister for Youth Hon. Amber-Jade Sanderson Minister for Environment MLA Minister for Climate Action Minister for Commerce Hon. -

MINUTES of the ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Held at CITY WEST

MINUTES Of The ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING Held At CITY WEST FUNCTION CENTRE West Perth On Friday, 22 September 2017 AGM Minutes 2017 Meeting commenced at 10:00hrs. WELCOME by David Sadler who introduced Andrew Murfin OAM JP, the Master of Ceremonies. Andrew Murfin acknowledged the three gentleman not present today, Hon Max Evans (who is sick), Clive Griffiths who is unable to attend, Cyril Fenn who passed away a couple of months ago. Andrew acknowledged Tony Kristicevic MLA - Member for Carine; only member of parliament present today as all Members of Parliament are always very busy but thank you for coming. He acknowledged, Nita Sadler, Margaret Thomas. APOLOGIES : These were accepted but not read due to the number. Derek & Carla Archer - Archer & Sons, Tom Wallace, Leigh & Linda Thompson - Thompson Funeral Homes, Timothy Bradley- Bowra & O'Dea, Victor Court, Charlotte Howell, Kay Cooper, Brian Mathlin - RWA Board Member, Jessica Shaw MLA, Lisa Baker MLA, Zac Kirjup MP, Reece Whitby MLA, Thelma Van Oyen, Mark Mcgown MLA, Peter Katsambanis MLA, Michelle Roberts MLA, Bill Johnson MLA, Mr Don Punch MLA, Simone McGurk MLA, TERRY REDMAN MLA, Bill Marmion MLA, Jessica Stojkovski MLA, Peter Rundle MP, Cassie Rowe MP, Simon Millman MLA, Lorraine Thompson JBAC, Emily Hamilton MLA, David Michael MLA, Vince Catania MLA, Colin Barnett MLA, Dean Nalder MLA, Jenny Seaton VIP, Carol Pope, Ben Wyatt MLA, Lisa Harvey MLA, Janine Freeman MLA, Shane & Kelly Bradley (Staff), Mike Nahan MLA, John Mcgrath MLA, Paul Papalia MLA, The Honourable Max Evans, Kyran O'Donnell MLA, Rita Saffioti MLA, Mick Murray MLA Nita lead the floor in singing the National Anthem. -

Ms Simone Mcgurk; Ms Libby Mettam; Ms Mia Davies; Mrs Jessica Stojkovski; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Ms Cassandra Rowe; Chair

Extract from Hansard [ASSEMBLY ESTIMATES COMMITTEE B — Thursday, 24 May 2018] p496b-522a Mr Sean L'Estrange; Ms Simone McGurk; Ms Libby Mettam; Ms Mia Davies; Mrs Jessica Stojkovski; Mr Yaz Mubarakai; Ms Cassandra Rowe; Chair Division 33: Communities — Services 1 to 10, Child Protection; Women’s Interests; Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence; Community Services, $786 480 000 — Mr I.C. Blayney, Chair. Ms S.F. McGurk, Minister for Child Protection; Women’s Interests; Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence; Community Services. Mr G. Searle, Director General. Ms. J. Tang, Assistant Director General, Child Protection and Family Support. Mr B. Jolly, Assistant Director General, Commissioning and Sector Engagement. Mr L. Carren, Executive Director, Business Services. Mr. S. Hollingworth, Executive Director, Housing and Homelessness. Ms T. Pritchard, Director, Finance. Mr D. Settelmaier, Senior Policy Adviser. Ms C. Irwin, Chief of Staff, Minister for Child Protection. [Witnesses introduced.] The CHAIR: This estimates committee will be reported by Hansard. The daily proof Hansard will be available the following day. It is the intention of the Chair to ensure that as many questions as possible are asked and answered and that both questions and answers are short and to the point. The estimates committee’s consideration of the estimates will be restricted to discussion of those items for which a vote of money is proposed in the consolidated account. Questions must be clearly related to a page number, item, program or amount in the current division. Members should give these details in preface to their question. If a division or service is the responsibility of more than one minister, a minister shall be examined only in relation to their portfolio responsibilities. -

Mrs Jessica Stojkovski, MLA (Member for Kingsley)

PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA INAUGURAL SPEECH Mrs Jessica Stojkovski, MLA (Member for Kingsley) Legislative Assembly Address-in-Reply Thursday, 18 May 2017 Reprinted from Hansard Legislative Assembly Thursday, 18 May 2017 ____________ ADDRESS-IN-REPLY Motion Resumed from 17 May on the following motion moved by Ms J.J. Shaw — That the following Address-in-Reply to Her Excellency’s speech be agreed to — To Her Excellency the Honourable Kerry Sanderson, AC, Governor of the State of Western Australia. May it please Your Excellency — We, the Legislative Assembly of the Parliament of the State of Western Australia in Parliament assembled, beg to express loyalty to our Most Gracious Sovereign and to thank Your Excellency for the speech you have been pleased to address to Parliament. MRS J.M.C. STOJKOVSKI (Kingsley) [9.16 am]: Mr Speaker, may I congratulate you on your election to the role of Speaker. I would like to acknowledge the traditional owners of the land on which we meet, the Whadjuk people of the Noongar nation, and may I pay my respects to elders past, present and emerging. I would like to thank the former member for Kingsley, Andrea Mitchell, for her service to the people of Kingsley for the last eight and a half years. I am proud to follow her as the fourth member for Kingsley, all of whom, since the creation of the electorate in 1989, have been women. I thank the people of Kingsley for their faith in me and I am humbled to stand in this place as their local member. -

Mcgowan Government Cabinet Hon Mark Mcgowan MLA

McGowan Government Cabinet Hon Mark McGowan MLA Premier; Treasurer; Minister for Public Sector Management; Federal-State Relations Hon Roger Cook MLA Deputy Premier; Minister for Health; Medical Research; State Development, Jobs and Trade; Science Hon Sue Ellery MLC Minister for Education and Training; Leader of the Legislative Council Hon Stephen Dawson MLC Minister for Mental Health; Aboriginal Affairs; Industrial Relations; Deputy Leader of the Legislative Council Hon Alannah MacTiernan MLC Minister for Regional Development; Agriculture and Food; Hydrogen Industry Hon David Templeman MLA Minister for Tourism; Culture and the Arts; Heritage; Leader of the House Hon John Quigley MLA Attorney General; Minister for Electoral Affairs Hon Paul Papalia MLA Minister for Police; Road Safety; Defence Industry; Veterans Issues Hon Bill Johnston MLA Minister for Mines and Petroleum; Energy; Corrective Services Hon Rita Saffioti MLA Minister for Transport; Planning; Ports Hon Dr Tony Buti MLA Minister for Finance; Lands; Sport and Recreation; Citizenship and Multicultural Interests Hon Simone McGurk MLA Minister for Child Protection; Women's Interests; Prevention of Family and Domestic Violence; Community Services Hon Dave Kelly MLA Minister for Water; Forestry; Youth Hon Amber-Jade Sanderson Minister for Environment; Climate Action; Commerce MLA Hon John Carey MLA Minister for Housing; Local Government Hon Don Punch MLA Minister for Disability Services; Fisheries; Innovation and ICT; Seniors and Ageing Hon Reece Whitby MLA Minister for Emergency -

WA State Election 2017

PARLIAMENTAR~RARY ~ WESTERN AUSTRALIA 2017 Western Australian State Election Analysis of Results Election Papers Series No. 1I2017 PARLIAMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA WESTERN AUSTRALIAN STATE ELECTION 2017 ANALYSIS OF RESULTS by Antony Green for the Western Australian Parliamentary Library and Information Services Election Papers Series No. 1/2017 2017 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent from the Librarian, Western Australian Parliamentary Library, other than by Members of the Western Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. The views expressed in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Western Australian Parliamentary Library. Western Australian Parliamentary Library Parliament House Harvest Terrace Perth WA 6000 ISBN 9780987596994 May 2017 Related Publications • 2015 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2015. • Western Australian State Election 2013 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2013. • 2011 Redistribution Western Australia – Analysis of Final Electoral Boundaries by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2011. • Western Australian State Election 2008 Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election paper series 1/2009. • 2007 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2007 • Western Australian State Election 2005 - Analysis of Results by Antony Green. Election papers series 2/2005. • 2003 Electoral Distribution Western Australia: Analysis of Final Boundaries Election papers series 2/2003. -

IN THIS ISSUE Let’S Go Travelling • Join Have a Go News on a Day Trip to Antarctica • Josephine Allison in Singapore • Discover Kangaroo Island • WA Wildflowers

SINGLE? FREE We have your partner MONTHLY Dedicated matchmakers helping you to meet genuine, suitable partners. Forget ‘online’ dating! Be matched safely WA’s Best Value Range of and personally by people who care. tŝůĚŇŽǁĞƌdŽƵƌƐ See Friend to Friend page for Solutions Contacts Column Call for our Spring Brochure SOLUTIONS 9371 0380 PH: 1800 999 677 caseytours.com.au LIFESTYLE OPTIONS FOR THE MATURE WESTERN AUSTRALIAN www.solutionsmatchmaking.com.au PRINT POST 100022543 VOLUME 28 NO. 03 ISSUE NO. 319 OCTOBER 2018 Proud partner AGL - It’s gas, plus a whole lot more Age is no barrier... IN THIS ISSUE let’s go travelling • Join Have a Go News on a day trip to Antarctica • Josephine Allison in Singapore • Discover Kangaroo Island • WA Wildflowers Josephine Allison interviews Hungerford Award contender Trish Versteegen • Seniors Week Events Guide Liftout 24 pages • Where opinions matter • Food & Wine - reviews, recipes and more COMPETITIONS/GIVEAWAYS Ad Words - $200 Shopping voucher TICKETS - UnWined Subiaco, Treasured Craft Creations, Pipe Organ Plus, St Mary’s Cathedral BOOK - Where History Happened FILMS - Westwood, First Man, British Film Festival SEE THE WEBSITE FOR MORE Visit www.haveagonews.com.au SUPPORTING SENIORS’ RECREATION COUNCIL OF WA (INC) Established 1991 Celebrating 27 years in 2018 ,ŝŐŚYƵĂůŝƚLJ͕'ƌĞĂƚdĂƐƟŶŐDĞĂůƐ Clockwise from top left; Entertainment galore is available throughout the day -There’s so many activities to try at Have a Go Da y - Seniors Minister Mick Murray struts his stuff - Prime Movers demonstrate their moves to music EVERYONE is invited to come Over 55 Walking Association. belly dancers in action and the available. Visitors to the hospital- down to Burswood Park on For people who love to chal- Prime Movers will show that ex- ity tent can have a cuppa, relax Wednesday 14 November for the lenge themselves physically ercise to music can be lots of fun.