Prevalence and Predictors of Overweight and Obesity Among Somalis in Norway and Somaliland: a Comparative Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ministry of Education & Higher Education Republic of Somaliland

Ministry of Education & Higher Education Republic of Somaliland Global Partnership for Education Programme Document 2013-2016 Final FOREWORD We aim to strengthen our Education Sector and provide every child in Somaliland quality education, with well-prepared teachers using an effective curriculum. Our vision for the development of the education system is in Somaliland is grounded in the following premise: Every child in Somaliland living in every region has the right to a quality education. Providing quality education that caters to students’ needs should be a primary objective, from early childhood education through to further and higher education. The importance of quality teaching for quality education cannot be underestimated. To achieve this, teachers at all levels of education must be trained appropriately. Teachers should continue their professional development through a period of induction into the profession with the support of supervisors and mentors and should have access throughout their careers to high quality continuous professional development and learning. The teaching and learning environment should be designed in such a way that it supports teachers and all education officials in their missions to educate our children. Quality education nurtures human talent and creativity and will contribute to the personal and professional development of the individual person, as well as to the social, cultural, moral, economic, political and environmental development of society at large. We know that quality education promotes peace, solidarity, inclusion, a commitment to a sustainable environment, and international and intercultural understanding. The Ministry of Education & Higher Education appreciates the assistance of the Global Partnership for Education for improving the quality of education in Somaliland through support to teachers. -

Somaliland: the Strains of Success

Somaliland: The Strains of Success Crisis Group Africa Briefing N°113 Nairobi/Brussels, 5 October 2015 I. Overview Somaliland’s hybrid system of tri-party democracy and traditional clan-based gov- ernance has enabled the consolidation of state-like authority, social and economic recovery and, above all, relative peace and security but now needs reform. Success has brought greater resources, including a special funding status with donors – especially the UK, Denmark and the European Union (EU) – as well as investment from and diplomatic ties with Turkey and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), though not inter- national recognition. It is increasingly part of the regional system; ties are especially strong with Ethiopia and Djibouti. Given the continued fragility of the Somalia Federal Government (SFG), which still rejects its former northern region’s independence claims, and civil war across the Gulf of Aden in Yemen, Somaliland’s continued stabil- ity is vital. This in turn requires political reforms aimed at greater inclusion, respect for mediating institutions (especially the professional judiciary and parliament) and a regional and wider internationally backed framework for external cooperation and engagement. Successful state building has, nevertheless, raised the stakes of holding – and los- ing – power. While Somaliland has remained largely committed to democratic gov- ernment, elections are increasingly fraught. Fear of a return to bitter internal conflict is pushing more conservative politics: repression of the media and opposition, as well as resistance to reforming the increasingly unsustainable status quo. Recurrent po- litical crises and delayed elections (now set for March 2017) risk postponing much needed internal debate. The political elites have a limited window to decide on steps necessary to rebuild the decaying consensus, reduce social tensions and set an agenda for political and institutional reform. -

UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund for Somalia QUARTERLY REPORT

UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund for Somalia QUARTERLY REPORT 1 January – 31 March 2016 1 UN MPTF QUARTERLY REPORT: 1 January – 31 March 2016 Dear Colleagues, dear Partners, Welcome to the second quarterly report of the UN Multi-Partner Trust Fund (UN MPTF). Following 2015, which focused on getting the joint programmes designed and launched, the first quarter of 2016 was dedicated almost entirely on implementation and on the expansion or extension of current efforts. All of this is happening under the strong guidance and oversight of the SDRF structures, which are now robust platforms for genuine policy engagement between national and regional actors and between Somali representatives and the international community. As Somalia approaches a number of key milestones, a number of Joint Programmes in fact experienced acceleration in their activities, which are highlighted in this report. At the same time, new initiatives were started during the reporting period. I am particularly pleased to report on the launch of the UN MPTF National Window, which allows fund transfers directly to national entities. In this regard, a pilot project of $2 million investment from the Peacebuilding Fund for the rehabilitation of small-scale infrastructure is now underway. The project channels funds directly to the Central Bank of Somalia, on budget and on treasury, using the national financial systems under the oversight of the Ministry of Finance. In the design of the National Window and this project, the UN has collaborated very closely with the World Bank. As a result, a number of procedures have been harmonized, and capacity strengthening efforts are coordinated. -

ICT for Development and Empowering Success”

1st Conference and Exhibition on Somaliland ICT Somaliland ICT Conference 2019 Theme of the year “ICT for Development and Empowering Success” Participant of the conference on Somaliland ICT 2019 Prepared by: Abdirahman Mohamed Sh. Abdilahi Mohamed Ibrahim Saleban Institute for Personal and Organizational Development (IPOD)\ Hargeisa, Somaliland September 13, 2019 CONFERENCE SPONSORS Table of Contents Acronym ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction.................................................................................................................................................. 5 Background and Rationale of the Conference .......................................................................................... 5 Objectives of the Conference ...................................................................................................................... 6 Participants of the Conference ................................................................................................................... 6 Welcoming and Opening Statements ......................................................................................................... 6 Panel Discussions ....................................................................................................................................... 13 Presentations ............................................................................................................................................. -

Report on the Somaliland Presidential Election, 13Th November 2017

The Bartlett Development Planning Unit International Election Observation Mission The limits of consensus? Report on the Somaliland Presidential Election, 13th November 2017 by Michael Walls, Conrad Heine, Andrea Klingel, Carrie Goggin, Ahmed Farag, Susan Mwape with input from Rooble Mohamed and Short-Term Observers. dpu Development Planning Unit DPU http://www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/dpu/ If a hard copy is required, please contact the De- velopment Planning Unit (DPU) at the address at the bottom of the page. Institutions, organisations and booksellers should supply a Purchase Order when ordering a copy of this report. Where multiple copies are ordered, and the cost of postage and package is significant, the DPU may make a charge to cover costs. Copyright of this report lies with the authors and there are no restrictions on it being published elsewhere in any version or form. Graphics and layout: Luz Navarro Cover photograph: © Kate Stanworth The Bartlett The Bartlett The Bartlett Development Planning Unit | The Bartlett | University College London The Bartlett 34 Tavistock Square - London - WC1H 9EZ Tel: +44 (0)20 7679 1111 - Fax: +44 (0)20 7679 1112 - www.bartlett.ucl.ac.uk/dpu 1 International Election Observation Mission The limits of consensus? Report on the Somaliland Presidential Election, 13th November 2017 by Michael Walls, Conrad Heine, Andrea Klingel, Carrie Goggin, Ahmed Farag, Susan Mwape with input from Rooble Mohamed and Short-Term Observers. March 2018 Acknowledgements. We would like to express our help with transport, Saferworld (Abdijalil Dahir Afqarshe) appreciation to the Foreign and Commonwealth Office for providing additional observers, transport and for shar- (FCO) for providing the funding for the international elec- ing photographs taken by the photographer Kate Stan- tion observation mission and in particular to Rosie Tapper worth, and to the Maan-Soor Hotel for their flexibility and and Edward Prior for their support. -

SOMALIA National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP)

FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF SOMALIA National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) December, 2015 The designations employed and the presentation of material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document should be cited as follows: Ullah, Saleem and Gadain, Hussein 2016. National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP) of Somalia, FAO-Somalia. Contents Executive Summary .................................................................................................................... 6 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................. 12 1.1. Background to the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan: ............................. 12 1.2. Overview of the NBSAP development process in Somalia ........................................... 12 1.3. Structure of the National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan .................................. 16 1.4. Understanding biodiversity ............................................................................................ 17 1.5. Importance of biodiversity ............................................................................................. 17 1.6. Generic Profile of Somalia ............................................................................................ -

Migration and Conflict in the Horn of Africa: a Review of Recent Literature

January 2020 November 2019 SOASNovember 2019 November 2019 Migration and conflict in the Horn of Africa: a review of recent literature By Jessica Gregson: Independent Consultant The Research and Evidence Facility Consortium SOAS, University of London The University of Sahan Thornhaugh St, Manchester Nairobi, Kenya Russell Square, Arthur Lewis Building, www.sahan.global London WC1H 0XG Oxford Road, Conflict & Governance Key United Kingdom Manchester M13 9PL Expert: Vincent Chordi www.soas.ac.uk United Kingdom Senior Advocacy Officer: Team Leader: www.gdi.manchester.ac.uk Rashid Abdi Laura Hammond Migration & Development Research Coordinator: Project Manager and Key Expert: Oliver Bakewell Caitlin Sturridge Research Officer: Communications Manager: Research Team Leader: Louisa Brain Rose Sumner Lavender Mboya SOAS Thornhaugh St, This report was prepared by Jessica Gregson with Conflict in the Horn of Africa: a review of recent Russell Square, support from Oliver Bakewell and Louisa Brain. literature’, London: EU Trust Fund for Africa London WC1H 0XG (Horn of Africa Window) Research and Evidence United Kingdom This publication was produced with the financial Facility. www.soas.ac.uk support of the European Union. Its contents are Team Leader: the sole responsibility of the researchers and do For more information on the Research and Laura Hammond not necessarily reflect the views of the European Evidence Facility visit the website: Project Coordinator and Union or the EU Trust Fund for Africa. blogs.soas.ac.uk/ref-hornresearch Research Officer: Louisa Brain Suggested Citation: Research and Evidence Funded by the European Union Facility (REF). January 2020. ‘Migration and Emergency Trust Fund for Africa. Migration and conflict in the Horn of Africa: a review of recent literature Contents Introduction .......................................................................................................... -

Nature of the State in Somalia and Somaliland: the Conversations of the Statebuilding and Peacebuilding Processes Mohamed Haji Abdulahi Ingiriis

Reframing Narratives of Statebuilding and Peacebuilding in Africa The nature of the state in Somalia and Somaliland: The Conversations of the Statebuilding and Peacebuilding Processes Mohamed Haji Abdulahi Ingiriis Integrated Field Research Report This paper is a part of an African Leadership Centre Research project supported by the International Development Research Centre. The paper was presented at the project’s review and validation workshop convened on 18-19 April 2016 in Nairobi. The paper integrates the revised baseline studies, field research notes and reviewers comments. Contents Abstract .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 The Past Plunders and the Present Politics ......................................................................................... 7 The Disintegration and Development .................................................................................................. 12 The Poles of Power and Peacebuilding ................................................................................................ 13 The Statehood and Stateness ................................................................................................................... 19 Sovereignty and Sorrow ........................................................................................................................... -

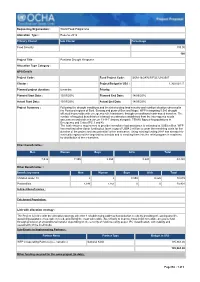

Requesting Organization : World Food Programme Allocation Type

Requesting Organization : World Food Programme Allocation Type : Reserve 2016 Primary Cluster Sub Cluster Percentage Food Security 100.00 100 Project Title : Puntland Drought Response Allocation Type Category : OPS Details Project Code : Fund Project Code : SOM-16/2470/R/FSC/UN/2507 Cluster : Project Budget in US$ : 1,300,001.15 Planned project duration : 6 months Priority: Planned Start Date : 15/03/2016 Planned End Date : 14/09/2016 Actual Start Date: 15/03/2016 Actual End Date: 14/09/2016 Project Summary : Following the drought conditions and the deteriorating food security and nutrition situation observed in the Puntland regions of Sool, Sanaag and parts of Bari and Nugal, WFP is targeting 5,580 drought affected households with emergency relief assistance through unconditional cash-based transfers. The number of targeted beneficiaries is based on estimates established from the inter-agency needs assessment undertaken between 13-18 February alongside FSNAU figures for populations in Emergency and Crisis (IPC 3 and 4). The total resource requirement to provide immediate food assistance is estimated at US$9 million. WFP has received other donor funding but faces a gap of US$4.2 million to cover the remaining costs for the duration of the project and any potential further assistance. Using existing funding WFP has already bio- metrically registered the targeted households and is enrolling them into the relief program in readiness for distribution of the e-transfers. Direct beneficiaries : Men Women Boys Girls Total 7,546 7,855 8,859 9,220 33,480 Other Beneficiaries : Beneficiary name Men Women Boys Girls Total Children under 18 0 0 8,859 9,220 18,079 Pastoralists 7,546 7,855 0 0 15,401 Indirect Beneficiaries : Catchment Population: Link with allocation strategy : The Project is in line with the allocation strategy objective 1 of addressing Address humanitarian needs by providing life-saving and life- sustaining assistance to people in need, prioritizing the most vulnerable. -

Emergency Plan of Action Operation Update Somalia: Drought

Emergency Plan of Action operation update Somalia: Drought Emergency appeal n° MDRSO005 GLIDE n° DR-2015-000134-SOM EPoA update n°: 4 Timeframe covered by this update: 9 Months Date of issue: 30/12/2016 Operation start date: March 2016 Operation timeframe: 15 Months (New end date 21 June 2017) Overall Operation budget: CHF 1,291,576 If Emergency Appeal operation, DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 129,394 Total estimated Red Cross and Red Crescent response to date: CHF 694,761 Appeal coverage:54 % N° of people being assisted: 78,990 beneficiaries (1365HH). Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: British Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, Red Cross of Monaco, Swedish Red Cross, The Canadian Red Cross Society, The Netherlands Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: NERAD(Somaliland) and Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management Agency (HADMA), UNOCHA, CARE International, SCI, DRC, ADESO, UNHCR, TASS, UNDP, WFP, UNICEF, FAO IRC, SCI, NRC, CARE International, Concern Worldwide, ISLAMIC RELIEF, ADESO, ADRA, ACF, DRC, UNDP, TASS, ECHO. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: This Emergency Appeal seeks1,291,576.00 Swiss francs in cash, kind or services to support the Somali Red Crescent Society assist 78,900 beneficiaries (1365 HH). Following the needs on the ground, the Emergency Appeal seeks an additional 6 months to be able to achieve its goal. The new end date is 21st June, 2017. A DREF loan of 129,394 Swiss francs was processed at the beginning of the APPEAL to support the start-up activities by SRCS. -

High Stakes for Somaliland's Presidential Elections

High stakes for Somaliland’s presidential elections Omar S Mahmood and Mohamed Farah The stakes are high for Somaliland’s presidential elections scheduled for 13 November 2017. After more than two years of delays, voters will finally have the chance to be heard. Given that President Ahmed Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ is stepping down, the contest will result in fresh leadership. This report sheds light on some of the pivotal political and security issues facing Somaliland at the time of these crucial elections, providing a background on the process and raising some key concerns. EAST AFRICA REPORT 15 | OCTOBER 2017 Introduction Key points The stakes are high for Somaliland’s presidential elections scheduled for The stakes for the 2017 13 November 2017. After more than two years of delays, voters will finally presidential elections are have the chance to make their voices heard. Given that President Ahmed high, and the vote is likely to Mohamed Mohamoud ‘Silanyo’ is not standing for re-election, the contest will be close. result in fresh leadership regardless of the outcome. This report aims to shed While some concerns exist light on some of the pivotal political and security issues facing Somaliland at regarding the electoral the time of these crucial elections, providing a background on the process campaign and acceptance and raising some key concerns going forward. of its outcome by all sides, the successful completion This report was written in partnership by the Institute for Security Studies of a voter register is likely to (ISS) and the Academy for Peace and Development (APD), a think tank mean that the vote will be based in Hargeisa. -

Emergency Plan of Action Operation Update Somalia: Drought

Emergency Plan of Action operation update Somalia: Drought Emergency appeal n° MDRSO005 GLIDE n° DR-2015-000134-SOM Operations update n°: 5 Timeframe covered by this update: 31 March – 31 December 2016 Date of issue: 13 February 2017 Operation timeframe: 15 months (New end date 21 June 2017) Overall Operation budget: CHF 1,291,576 DREF amount initially allocated: CHF 129,394 Total estimated Red Cross and Red Crescent Appeal coverage: 54 % response to date: CHF 694,761 N° of people being assisted: 78,990 beneficiaries (13,165 households). Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: British Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, Red Cross of Monaco, Swedish Red Cross, The Canadian Red Cross Society, The Netherlands Red Cross. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: NERAD(Somaliland) and Humanitarian Affairs and Disaster Management Agency (HADMA), UNOCHA, CARE International, SCI, DRC, ADESO, UNHCR, TASS, UNDP, WFP, UNICEF, FAO IRC, SCI, NRC, CARE International, Concern Worldwide, ISLAMIC RELIEF, ADESO, ADRA, ACF, DRC, UNDP, TASS, ECHO. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: This Emergency Appeal seeks 1,291,576.00 Swiss francs in cash, kind or services to support the Somali Red Crescent Society assist 78,990 beneficiaries (13,165households). Following the needs on the ground and the increased need to assist with negative coping strategies related to health, the Emergency Appeal seeks an additional 6 months to achieve its goal. The new end date is 21 June, 2017. A DREF loan of 129,394 Swiss francs was processed at the beginning of the APPEAL to support the start-up activities by SRCS.