A Mackay-Whitsunday Region Focus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

Southern and Western Queensland Region

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

Chapter 12 - Table of Contents

Cultural Heritage 12 DRAFT Chapter 12 - Table of Contents VERSION CONTROL: 28/06/2017 12 Cultural Heritage 12-1 12.1 Introduction 12-1 12.2 Indigenous Cultural Heritage 12-2 12.2.1 Statutory Framework 12-2 12.2.2 Paleo environment 12-5 12.2.3 Register Searches 12-6 12.2.4 Predicted Findings 12-13 12.3 Non-Indigenous Cultural Heritage 12-14 12.3.1 Statutory Framework 12-15 12.3.2 Results of Register Searches 12-19 12.3.3 Archaeological Potential 12-26 12.3.4 Significance Assessment 12-26 12.4 Potential Impacts and Mitigation Measures 12-30 12.5 Summary 12-31 Page i Draft EIS: 28/06/2017 List of Figures Figure 12-1. Location of the three shell middens recorded in the DATSIP database on or near Lindeman Island. ......................................................................................................................................... 12-6 Figure 12-2. DATSIP search results for the broader Whitsunday area. ....................................................... 12-11 Figure 12-3. Adderton 1898 home with residence on left and woolshed and yards on right. Photo taken in 1923 (Source Blackwood 1997, p. 131). .................................................................... 12-20 Figure 12-4. Tents and Home Beach 1928 (State Library Queensland). ..................................................... 12-21 Figure 12-5. Home Beach 1941 (QGTB Brochure, 1941). ........................................................................... 12-22 Figure 12-6. Accommodation circa 1960 (JOL, Record #371532). ............................................................. -

Monitoring Indigenous Heritage Within the Reef 2050 Integrated

© Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Institute of Marine Science) 2019 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISBN 978-0-6485892-0-4 This document is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logos of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Queensland Government, any other material protected by a trademark, content supplied by third parties and any photographs. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc/4.0/ A catalogue record for this publication is available from the National Library of Australia. This publication should be cited as: Jarvis, D., Hill, R., Buissereth, R., Moran, C., Talbot, L.D., Bullio, R., Grant, C., Dale, A., Deshong, S., Fraser, D., Gooch, M., Hale, L., Mann, M., Singleton, G. and Wren, L., 2019, Monitoring the Indigenous heritage within the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: Final Report of the Indigenous Heritage Expert Group, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville. Front cover image: Aerial drone image of Sawmill Beach, Whitsundays. © Commonwealth of Australia (GBRMPA), Photographer: Andrew Denzin. DISCLAIMER While reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth of Australia, represented by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

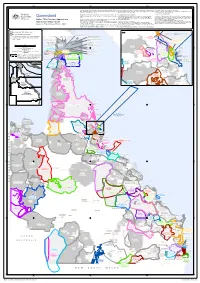

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court. -

Registration Test Decision

Registration test decision Application name Yuwibara People Name of applicant Gary Theodore Mooney, Jennifer Olive Darr, Melanie Roseveen Kemp NNTT file no. QC2013/007 Federal Court of Australia file no. QUD720/2013 Date application made 29 October 2013 I have considered this claim for registration against each of the conditions contained in ss. 190B and 190C of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). For the reasons attached, I am satisfied that each of the conditions contained in ss. 190B and C are met. I accept this claim for registration pursuant to s. 190A of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth). Date of decision: 9 January 2014 ___________________________________ Heidi Evans Delegate of the Native Title Registrar pursuant to sections 190, 190A, 190B, 190C, 190D of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) under an instrument of delegation dated 30 July 2013 and made pursuant to s. 99 of the Act. Shared country, shared future. Reasons for decision Introduction [1] This document sets out my reasons, as the Registrar’s delegate, for the decision to accept the application for registration pursuant to s. 190A of the Act. [2] Note: All references in these reasons to legislative sections refer to the Native Title Act 1993 (Cwlth) which I shall call ‘the Act’, as in force on the day this decision is made, unless otherwise specified. Please refer to the Act for the exact wording of each condition. Application overview and background [3] The Registrar of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) gave a copy of the Yuwibara People claimant application to the Native Title Registrar (the Registrar) on 1 November 2013 pursuant to s. -

AIATSIS Lan Ngua Ge T Hesaurus

AIATSIS Language Thesauurus November 2017 About AIATSIS – www.aiatsis.gov.au The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is the world’s leading research, collecting and publishing organisation in Australian Indigenous studies. We are a network of council and committees, members, staff and other stakeholders working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to carry out activities that acknowledge, affirm and raise awareness of Australian Indigenous cultures and histories, in all their richness and diversity. AIATSIS develops, maintains and preserves well documented archives and collections and by maximising access to these, particularly by Indigenous peoples, in keeping with appropriate cultural and ethical practices. AIATSIS Thesaurus - Copyright Statement "This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to The Library Director, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601." AIATSIS Language Thesaurus Introduction The AIATSIS thesauri have been made available to assist libraries, keeping places and Indigenous knowledge centres in indexing / cataloguing their collections using the most appropriate terms. This is also in accord with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Research Network (ATSILIRN) Protocols - http://aiatsis.gov.au/atsilirn/protocols.php Protocol 4.1 states: “Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues” We trust that the AIATSIS Thesauri will serve to assist in this task. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

North Queensland Land Council Native Title Representative Body Aboriginal Corporation Annual Report 2013-2014 Warning: While the North Queensland Land Council Native Title Representative Body Aboriginal Corporation (NQLC) has made every effort to ensure this Annual Report does not contain material of a culturally sensitive nature, Aboriginal people should be aware that there could be images of deceased people. Preparation of this report is funded by the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet. NQLC Annual Report 2013-14 Letter to Minister iii Contact Officer Ian Kuch Chief Executive Officer PO Box 679N CAIRNS NORTH QLD 4870 Telephone: (07) 4042 7000 Facsimile: (07) 4031 9489 Website: www.nqlc.com.au Designed and layout by ingeous studios. Photographs within this report are courtesy of Christine Howes, the National Native Title Tribunal (NNTT), and the NQLC staff. NQLC Annual Report 2013-14 Contents Board of Directors ix 1. Report by the Chairperson 1 2. Report by the Executive Officer 5 2.1 Summary of Significant Issues and Developments 6 2.2 Overview of Performance and Financial Results 9 2.3 Outlook for the following Year 11 3. The NQLC Overview 13 3.1 Overview Description of the NQLC 14 3.2 Roles and Functions 14 3.2.1 Legislation 14 3.2.2 Legislative Functions 14 3.2.3 Corporate Governance Policies 17 3.3 Organisational Structure 17 3.4 Outcome and Output Structure 17 3.5 Key Features-Strategic Plan, Operational Plan 18 4. Report on Performance 19 4.1 Review of Performance during the Year in relation to Strategic and Operational Plan -

0=AFRICAN Geosector

2= AUSTRALASIA geosector Observatoire Linguistique Linguasphere Observatory page 175 25= CENDRAWASIH covers the "Cendrawasih" or "North Central New Guinea" Indonesia; Papua New Guinea 5 reference area, composed of sets not covered by any geozone phylozone or by the "Trans-New Guinea" hypothesis, within the wider reference area of the "Papuan" hypotheses; comprising 25 sets of languages (= 76 outer languages) spoken by communities in Australasia centered on Cendrawasih Bay & (Bird's Head) Peninsula, extending from the Halmahera Islands in the west to Central New Guinea in the east: 25-A TOBELO+ TERNATE 25-B MOI+KALABRA 25-C ABUN 25-D YACH+ BRAT 25-E MPUR 25-F BORAI+ HATAM 25-G MEAH+ MANTION 25-H AWERA+ SAPONI* 25-I YAWA+ TARAU 25-J TUNGGARE+ BAPU 25-K WAREMBORI 25-L PAUWI 25-M BURMESO 25-N MASSEP 25-O VANIMO+ WARAPU 25-P KWOMTARI+ FAS 25-Q BAIBAI+ NAI 25-R PYU 25-S YURI+ USARI 25-T YADE 25-U BUSA 25-V AMTO+ MUSAN 25-W AMA+ NIMO 25-X POROME+ KIBIRI 25-Y BIBASA* 25-A TOBELO+ TERNATE HALMAHERA-NORTH Latin script set 25-AA TOBELO+ SAHU chain 25-AAA TOBELO+ TUGUTIL net 25-AAA-a Tobelo Halmahera… Morotai islands; émigré > Raja Ampat islands Indonesia (Maluku); (Irian Jaya) 4 25-AAA-aa boëng Halmahera-N.… Morotai-N. islands; émigré > Raja Ampat islands Indonesia (Maluku); émigré> (Irian 4 Jaya) 25-AAA-ab heleworuru Halmahera-N. islands: Tobelo+ Wasile Indonesia (Maluku) 3 25-AAA-ac dodinga Halmahera-C. island: Pintatu Indonesia (Maluku) 3 25-AAA-b Tugutil+ Kusuri Halmahera-N. -

Great Barrier Reef Traditional Owner Workshop Reef-Wide Forum 1St-3Rd May 2018

TitleReef second 2050 line OPTIONALGreat Barrier SUB LINEReef Traditional Owner Workshop Reef-wide Forum DATE 1st-3rd May 2018 Final Report Great Barrier Reef Traditional Owner Workshop Reef-wide Forum 1st-3rd May 2018. Final Report Disclaimer The funding bodies Reef and Rainforest Research Centre (RRRC) and CSIRO do not guarantee, and accept no legal liability whatsoever arising from or connected to, the use of or reliance on any material contained in this publication or in any material referenced in this publication. Information provided in this report is considered to be true and correct at the time of publication. Changes in the circumstances after time of publication may impact on the accuracy of this information and the authors give no assurance as to the accuracy of any information or advice contained in this publication. The authors recommend that users exercise their own skill and care with respect to their use of this publication and that users carefully evaluate the accuracy, currency, completeness and relevance of the material for their purposes. The material in this publication may include the views or recommendations of third parties, which do not necessarily reflect the views of the funding bodies, or indicate commitment to a particular course of action. Page 2 of 27 Contents Disclaimer .............................................................................................................................. 2 Contents ................................................................................................................................ -

(Title of the Thesis)*

HANDING OVER THE KEYS: INTERGENERATIONAL LEGACIES OF CARCERAL POLICY IN CANADA, AUSTRALIA, AND NEW ZEALAND by Linda Mussell A thesis submitted to the Department of Political Studies In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada April 2021 Copyright ©Linda Mussell, 2021 Abstract The impacts of criminalisation and imprisonment are felt throughout generations. Indigenous communities experience confinement on a hyper scale in countries that continue to grapple with colonial legacies, including Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. Policy changes have not been mitigating this reality and in many cases exacerbate experiences of harm. Different forms of confinement including imprisonment in prisons have been experienced intergenerationally (within and across generations) by some families and communities. With a goal of transformative change, this dissertation asks: how should Canada, Australia, and New Zealand reconfigure policy approaches to address hyper imprisonment and intergenerational imprisonment in partnership with Indigenous communities? To answer the research question, this dissertation uses Intersectionality-Based Policy Analysis (IBPA), a twelve-question framework that was developed by Olena Hankivsky et al. (2012) to aid policy analysts and researchers in using an intersectional lens to examine policy issues. My application of IBPA to this issue draws on literature and policy material and is grounded in 106 qualitative interviews with 124 Indigenous and non-Indigenous people in policy, frontline services, academia, and with those who have experienced imprisonment personally or as a family member of a prisoner. Participants report significant impacts of imprisonment on families and communities, which greatly impact Indigenous people over generations. Participants identified a diverse range of changes needed to address intergenerational imprisonment of Indigenous people. -

Indigenous Languages Project; Wordlists

Say G’day in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Language” ”Say G’day in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Language” The State Library of Queensland in partnership with Yugambeh Museum, Language and Heritage Research Centre, Indigenous Language Centres and other community groups would like to invite you to: “Say G’day in an Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander Language!” During NAIDOC Week (3-10 July 2016), we encouraged Queenslanders to say ‘g’day’ in their local Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander language; and with the 2017 NAIDOC Theme being ‘Our Languages Matter’ it is a timely reminder of the importance of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages. In Queensland there are over 100 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages and dialects; today only about 30 are spoken on a daily basis! To help raise awareness and promote Queensland’s Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages, we are asking schools, organisations, communities, individuals, etc. to find out their local word for ‘G’day’ or ‘Hello’ and use it during this week. Talk to your local community to find out the word and how to say it! Use your library, IKC, language centre to research other local words! Share this new greeting with friends, families and others during the week! Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Language Wordlists for ‘g’day’, ‘hello’ and other greetings are posted on the State Library and Yugambeh Museum websites: SLQ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Webpages: www.slq.qld.gov.au/resources/atsi/languages/word-lists/say-gday-in-an-indigenous-language Yugambeh Museum Website: www.yugambeh.com G’day in Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages The State Library of Queensland acknowledges that the language heritage and knowledge of these wordlists always remains with the Traditional Owners, language custodians and community members of the respective language nations.