Chapter 12 - Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchOnline at James Cook University Final Report Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale, Melissa George, Rosemary Hill and Duane Fraser Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? Allan Dale1, Melissa George2, Rosemary Hill3 and Duane Fraser 1The Cairns Institute, James Cook University, Cairns 2NAILSMA, Darwin 3CSIRO, Cairns Supported by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme Project 3.9: Indigenous capacity building and increased participation in management of Queensland sea country © CSIRO, 2016 Creative Commons Attribution Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward? is licensed by CSIRO for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Australia licence. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: 978-1-925088-91-5 This report should be cited as: Dale, A., George, M., Hill, R. and Fraser, D. (2016) Traditional Owners and Sea Country in the Southern Great Barrier Reef – Which Way Forward?. Report to the National Environmental Science Programme. Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited, Cairns (50pp.). Published by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre on behalf of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme (NESP) Tropical Water Quality (TWQ) Hub. The Tropical Water Quality Hub is part of the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Programme and is administered by the Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited (RRRC). -

Many Voices Queensland Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Action Plan

Yetimarala Yidinji Yi rawarka lba Yima Yawa n Yir bina ach Wik-Keyangan Wik- Yiron Yam Wik Pa Me'nh W t ga pom inda rnn k Om rungu Wik Adinda Wik Elk Win ala r Wi ay Wa en Wik da ji Y har rrgam Epa Wir an at Wa angkumara Wapabura Wik i W al Ng arra W Iya ulg Y ik nam nh ar nu W a Wa haayorre Thaynakwit Wi uk ke arr thiggi T h Tjung k M ab ay luw eppa und un a h Wa g T N ji To g W ak a lan tta dornd rre ka ul Y kk ibe ta Pi orin s S n i W u a Tar Pit anh Mu Nga tra W u g W riya n Mpalitj lgu Moon dja it ik li in ka Pir ondja djan n N Cre N W al ak nd Mo Mpa un ol ga u g W ga iyan andandanji Margany M litja uk e T th th Ya u an M lgu M ayi-K nh ul ur a a ig yk ka nda ulan M N ru n th dj O ha Ma Kunjen Kutha M ul ya b i a gi it rra haypan nt Kuu ayi gu w u W y i M ba ku-T k Tha -Ku M ay l U a wa d an Ku ayo tu ul g m j a oo M angan rre na ur i O p ad y k u a-Dy K M id y i l N ita m Kuk uu a ji k la W u M a nh Kaantju K ku yi M an U yi k i M i a abi K Y -Th u g r n u in al Y abi a u a n a a a n g w gu Kal K k g n d a u in a Ku owair Jirandali aw u u ka d h N M ai a a Jar K u rt n P i W n r r ngg aw n i M i a i M ca i Ja aw gk M rr j M g h da a a u iy d ia n n Ya r yi n a a m u ga Ja K i L -Y u g a b N ra l Girramay G al a a n P N ri a u ga iaba ithab a m l j it e g Ja iri G al w i a t in M i ay Giy L a M li a r M u j G a a la a P o K d ar Go g m M h n ng e a y it d m n ka m np w a i- u t n u i u u u Y ra a r r r l Y L a o iw m I a a G a a p l u i G ull u r a d e a a tch b K d i g b M g w u b a M N n rr y B thim Ayabadhu i l il M M u i a a -

National Parks Contents

Whitsunday National Parks Contents Parks at a glance ...................................................................... 2 Lindeman Islands National Park .............................................. 16 Welcome ................................................................................... 3 Conway National Park ............................................................. 18 Be inspired ............................................................................... 3 Other top spots ...................................................................... 22 Map of the Whitsundays ........................................................... 4 Boating in the Whitsundays .................................................... 24 Plan your getaway ..................................................................... 6 Journey wisely—Be careful. Be responsible ............................. 26 Choose your adventure ............................................................. 8 Know your limits—track and trail classifications ...................... 27 Whitsunday Islands National Park ............................................. 9 Connect with Queensland National Parks ................................ 28 Whitsunday Ngaro Sea Trail .....................................................12 Table of facilities and activities .........see pages 11, 13, 17 and 23 Molle Islands National Park .................................................... 13 Parks at a glance Wheelchair access Camping Toilets Day-use area Lookout Public mooring Anchorage Swimming -

Southern and Western Queensland Region

138°0'E 140°0'E 142°0'E 144°0'E 146°0'E 148°0'E 150°0'E 152°0'E 154°0'E DOO MADGE E S (! S ' ' 0 Gangalidda 0 ° QUD747/2018 ° 8 8 1 Waanyi People #2 & Garawa 1 (QC2018/004) People #2 Warrungnu [Warrungu] Girramay People Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on boundaries with areas excluded or discrete boundaries of areas being claimed) as determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for they have been recognised by the Federal Court process. databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at GE ORG E TO W N People #2 Girramay Gkuthaarn and (! People #2 (! CARDW EL L that portion where their data has been used. Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 Kukatj People map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 CARPENTARIA Tagalaka Southern and WesternQ UD176/2T0o2p0ographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents Ewamian People QUD882/2015 Gurambilbarra Wulguru2k0a1b5a. Mada Claim The applications shown on the map include: and the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give People #3 GULF REGION Warrgamay People (QC2020/N00o2n) freehold land tenure sourced from Department of Resources (QLD) March 2021. -

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic Studies of the Cranial Shape The

82 3.3.4.4.3 Ecogeographic studies of the cranial shape The measurement of the human head of both the living and dead has long been a matter of interest to a variety of professions from artists to physicians and latterly to anthropologists (for a review see Spencer 1997c). The shape of the cranium, in particular, became an important factor in schemes of racial typology from the late 18th Century (Blumenbach 1795; Deniker 1898; Dixon 1923; Haddon 1925; Huxley 1870). Following the formulation of the cranial index by Retzius in 1843 (see also Sjovold 1997), the classification of humans by skull shape became a positive fashion. Of course such classifications were predicated on the assumption that cranial shape was an immutable racial trait. However, it had long been known that cranial shape could be altered quite substantially during growth, whether due to congenital defect or morbidity or through cultural practices such as cradling and artificial cranial deformation (for reviews see (Dingwall 1931; Lindsell 1995). Thus the use of cranial index of racial identity was suspect. Another nail in the coffin of the Cranial Index's use as a classificatory trait was presented in Coon (1955), where he suggested that head form was subject to long term climatic selection. In particular he thought that rounder, or more brachycephalic, heads were an adaptation to cold. Although it was plausible that the head, being a major source of heat loss in humans (Porter 1993), could be subject to climatic selection, the situation became somewhat clouded when Beilicki and Welon demonstrated in 1964 that the trend towards brachycepahlisation was continuous between the 12th and 20th centuries in East- Central Europe and thus could not have been due to climatic selection (Bielicki & Welon 1964). -

Mackay HHS Consumer and Community Engagement Strategy

Mackay Hospital and Health Service Consumer and Community Engagement Strategy 2020 - 2024 Enhance communication and Build a culture of person, Strengthen diverse connections patient engagement family and community- and collaborations centred care Mackay Hospital and Health Service Published by the State of Queensland (Mackay Hospital and Health Service), November 2020. This document is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au © State of Queensland (Mackay Hospital and Health Service) 2020 You are free to copy, communicate and adapt the work, as long as you attribute the State of Queensland (Mackay Hospital and Health Service). For more information or to access the summarised Snapshot Strategy document please contact: Community Engagement Team, Mackay Hospital and Health Service, PO Box 5580, Mackay MC 4741, [email protected], phone (07) 4885 6801. An electronic version of this document is available at www.mackay.health.qld.gov.au/get-involved Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander peoples and Australian South Sea Islander peoples are advised that this publication may contain words, names, images and descriptions of people who have passed away. Definition of consumer We are all users of the health system. Throughout this document we refer to people as patients and consumers. These words are used interchangeably to describe people who use, or are potential users, of health services. The term consumer representative is used to describe someone who has taken up a formal role to advocate on behalf on health consumers in partnership activities with a desire to improve healthcare for all (Health Consumers Queensland, 2018). -

The Sea People

i r terra australis 20 l The Sea People HO I AT I THE WHITSUNDAY ISLANDS, CENTRAL QUEENSLAND Pandanus Online Publications, found at the Pandanus Books web site, presents additional material relating to this book. www.pandanusbooks.com.au Terra Australis reports the results of archaeological and related research within the region south and east of Asia, though mainly Australia, New Guinea and Island Melanesia - lands that remained terra australis incognita to generations of prehistorians. Its subject is the settlement of the diverse environments in this isolated quarter of the globe by peoples who have maintained their discrete and traditional ways of life into the recent recorded or remembered past and at times into the observable present. Since the beginning of the series, the basic colour on the spine and cover has distinguished the regional distribution of topics as follows: ochre for Australia, green for New Guinea, red for South-East Asia and blue for the Pacific Islands. From 2001, issues with a gold spine will include conference proceedings, edited papers and monographs which in topic or desired format do not fit easily within the original arrangements. All volumes are numbered within the same series. List of volumes in Terra Australis Volume 1: Burrill Lake and Currarong: coastal sites in southern New South Wales. R.J. Lampert (1971) Volume 2: 01 Tumbuna: archaeological excavations in the eastern central Highlands, Papua New Guinea. J.P. White (1972) Volume 3: New Guinea Stone Age Trade: the geography and ecology of traffic in the interior. I. Hughes (1977) Volume 4: Recent Prehistory in Southeast Papua. -

2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022

DRAFT V20 2019 Queensland Bushfires State Recovery Plan 2019-2022 Working to recover, rebuild and reconnect more resilient Queensland communities following the 2019 Queensland Bushfires August 2020 to come Document details Interpreter Security classification Public The Queensland Government is committed to providing accessible services to Queenslanders from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. If you have Date of review of security classification August 2020 difficulty in understanding this report, you can access the Translating and Interpreting Authority Queensland Reconstruction Authority Services via www.qld.gov.au/languages or by phoning 13 14 50. Document status Final Disclaimer Version 1.0 While every care has been taken in preparing this publication, the State of Queensland accepts no QRA reference QRATF/20/4207 responsibility for decisions or actions taken as a result of any data, information, statement or advice, expressed or implied, contained within. ISSN 978-0-9873118-4-9 To the best of our knowledge, the content was correct at the time of publishing. Copyright Copies This publication is protected by the Copyright Act 1968. © The State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority), August 2020. Copies of this publication are available on our website at: https://www.qra.qld.gov.au/fitzroy Further copies are available upon request to: Licence Queensland Reconstruction Authority This work is licensed by State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority) under a Creative PO Box 15428 Commons Attribution (CC BY) 4.0 International licence. City East QLD 4002 To view a copy of this licence, visit www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Phone (07) 3008 7200 In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt this annual report, as long as you attribute [email protected] the work to the State of Queensland (Queensland Reconstruction Authority). -

Skin, Kin and Clan: the Dynamics of Social Categories in Indigenous

Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA Skin, Kin and Clan THE DYNAMICS OF SOCIAL CATEGORIES IN INDIGENOUS AUSTRALIA EDITED BY PATRICK MCCONVELL, PIERS KELLY AND SÉBASTIEN LACRAMPE Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of Australia ISBN(s): 9781760461638 (print) 9781760461645 (eBook) This title is published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). The full licence terms are available at creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ legalcode Cover design and layout by ANU Press. Cover image Gija Kinship by Shirley Purdie. This edition © 2018 ANU Press Contents List of Figures . vii List of Tables . xi About the Cover . xv Contributors . xvii 1 . Introduction: Revisiting Aboriginal Social Organisation . 1 Patrick McConvell 2 . Evolving Perspectives on Aboriginal Social Organisation: From Mutual Misrecognition to the Kinship Renaissance . 21 Piers Kelly and Patrick McConvell PART I People and Place 3 . Systems in Geography or Geography of Systems? Attempts to Represent Spatial Distributions of Australian Social Organisation . .43 Laurent Dousset 4 . The Sources of Confusion over Social and Territorial Organisation in Western Victoria . .. 85 Raymond Madden 5 . Disputation, Kinship and Land Tenure in Western Arnhem Land . 107 Mark Harvey PART II Social Categories and Their History 6 . Moiety Names in South-Eastern Australia: Distribution and Reconstructed History . 139 Harold Koch, Luise Hercus and Piers Kelly 7 . -

Monitoring Indigenous Heritage Within the Reef 2050 Integrated

© Commonwealth of Australia (Australian Institute of Marine Science) 2019 Published by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority ISBN 978-0-6485892-0-4 This document is licensed for use under a Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logos of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and the Queensland Government, any other material protected by a trademark, content supplied by third parties and any photographs. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc/4.0/ A catalogue record for this publication is available from the National Library of Australia. This publication should be cited as: Jarvis, D., Hill, R., Buissereth, R., Moran, C., Talbot, L.D., Bullio, R., Grant, C., Dale, A., Deshong, S., Fraser, D., Gooch, M., Hale, L., Mann, M., Singleton, G. and Wren, L., 2019, Monitoring the Indigenous heritage within the Reef 2050 Integrated Monitoring and Reporting Program: Final Report of the Indigenous Heritage Expert Group, Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Townsville. Front cover image: Aerial drone image of Sawmill Beach, Whitsundays. © Commonwealth of Australia (GBRMPA), Photographer: Andrew Denzin. DISCLAIMER While reasonable effort has been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth of Australia, represented by the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. -

Mapping the Cultural Atlas of North Queensland

Mapping the Cultural Atlas of North Queensland: Ronald “Tonky” Logan a Case Study Abstract The ‘Cultural Atlas’ proposed by the PIP (People, Identity, Place) research cluster at James Cook University aims to contextualize cultural communities and artists in North Queensland into a comprehensive profile. Case study Ronald “Tonky” Logan is a North Queensland Aboriginal Country Western musician. The secondary theme of this article is the appropriation of Country Western music by Australian Aboriginal groups as traditional music. This article draws on research by Dunbar-Hall & Gibson (2004), who demonstrate the relevance of contemporary music within Australian Aboriginal contexts, based on location and geography, as a means of establishing people, identity and place. Dr. David Salisbury James Cook University School of Creative Arts Digital Sound Introduction In 2005 the PIP (People, Identity, and Place) research cluster of James Cook University held an annual seminar during which the concept of initiating a Cultural Atlas was proposed. In March 2006 a PIP Cultural Atlas meeting was held and basic concepts were proposed including some preliminary boundaries of latitude 18, south to Bowen and Hayman Island, west to Mt. Isa and north covering the Gulf region (the Torres Strait Islands are not included). Possible outputs could be a Website as a primary means to maintain a collection of data and resources for tourism, focusing on eco and cultural-tourism CD’s and DVD’s. Initially this article aims to establish the context in which the subject of this case study, Ronald ‘Tonky’ Logan, performs and lives by outlining a brief history of Aboriginality in North Queensland along with a brief history of Aboriginal music in the region. -

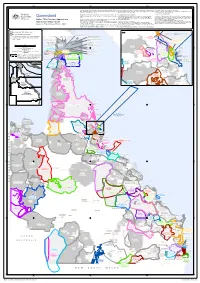

Queensland for That Map Shows This Boundary Rather Than the Boundary As Per the Register of Native Title Databases Is Required

140°0'E 145°0'E 150°0'E Claimant application and determination boundary data compiled from NNTT based on Where the boundary of an application has been amended in the Federal Court, the determination, a search of the Tribunal's registers and data sourced from Department of Resources (Qld) © The State of Queensland for that map shows this boundary rather than the boundary as per the Register of Native Title databases is required. Further information is available from the Tribunals website at portion where their data has been used. Claims (RNTC), if a registered application. www.nntt.gov.au or by calling 1800 640 501 © Commonwealth of Australia 2021 Topographic vector data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) 2006. The applications shown on the map include: Maritime boundaries data is © Commonwealth of Australia (Geoscience Australia) - registered applications (i.e. those that have complied with the registration test), The Registrar, the National Native Title Tribunal and its staff, members and agents and Queensland 2006. - new and/or amended applications where the registration test is being applied, the Commonwealth (collectively the Commonwealth) accept no liability and give no - unregistered applications (i.e. those that have not been accepted for registration), undertakings guarantees or warranties concerning the accuracy, completeness or As part of the transitional provisions of the amended Native Title Act in 1998, all - compensation applications. fitness for purpose of the information provided. Native Title Claimant Applications applications were taken to have been filed in the Federal Court. In return for you receiving this information you agree to release and Any changes to these applications and the filing of new applications happen through Determinations shown on the map include: indemnify the Commonwealth and third party data suppliers in respect of all claims, and Determination Areas the Federal Court.