International Culinary Influence on Street Food: an Observatory Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Menu Dapur 2019.09

BREAKFAST MENU ALL DAY MENU ALL DAY MENU Served until 11am Main Course Dishes Comfort on a plate Continental Breakfast £7.50 Beef rendang £12.50 Soto Ayam Tanjung Puteri £10.50 A selection of bread, pastries and viennoiserie with a selection of jam and Slow cooked beef in a myriad of spices, infused with aromatics, Nasi Impit (compressed rice cubes) OR Bihun (rice vermicelli) in hearty, spiced spread. Unlimited amount of orange juice, tea & coffee enriched with creamy coconut milk and kerisik chicken broth served with shredded chicken, begedil, beansprouts, spring onion and fried shallots. Accompanied by fiery sambal kicap (soy sauce with chilli) on the side) Full Halal English Breakfast £10.90 Ayam Goreng Bawang Putih £9.00 Perfectly British, and HALAL. 2 rashers of turkey bacon, 2 sausages, a fried Chicken marinade in garlic and deep fried egg, 2 hash browns, beans, tomatoes and toasts. Bihun Sup Brisket £9.50 Bihun (rice vermicelli) soaked in beef broth laden with tender brisket slices, Seabass Tanjung Tualang £13.50 home made beef balls, garnished with choi sum, tofu pieces, fried shallot and Fried seabass doused in our homemade special sauce home made chilli oil. Sambal udang petai £11.50 Kari Laksa Majidee £10.50 Prawn sambal with stinky beans Mee/Bihun in our kari laksa broth served with puffed tofu, fishballs, chicken, ALL DAY MENU green beans, stuffed chilli and our home made chili sambal Broccoli Berlada [v] £6.50 Broccoli stir fried with garlic and chilli. Nasi Lemak Dapur £12.50 Starters Fluffy and creamy coconut rice infused with fragrant pandan leaves served with ayam goreng, beef rendang, sambal, boiled egg, cucumber slices, Beans and Taugeh goreng kicap [v] £6.50 fried peanuts and anchovies. -

Snacks and Salads Chefs Specialities Sides Rice and Noodles Dessert!

snacks and salads chefs specialities pork and blood sausage corn dog duck and foie gras wonton pickled chili, sweet soy, hoisinaise, superior stock, mushrooms, dates gado gado roast garlic clams sweet potato, beet, spinach, green bean, coconut, creamed spinach, bone marrow, tempeh, egg, spicy peanut sauce, shrimp chip pickled chili banana leaf smoked duck salad smoked pork rib char siu citrus, chili, basil, lime leaf, coconut, apple glaze, jalapeno, leek. peanut, warm spice wok fried tofu charred lamb neck satay cauliflower, pickled raisins, anchovy, sweet soy, cucumber, compressed rice cake celery, peanut, chili crisp wok fried cabbage grilled stuffed quail dried shrimp, crispy peanut surendeng sticky rice, house chinese sausage, dr pepper glaze, chili, herbs sweet potato and zucchini fritters scallion, sweet soy pork belly char siu bing sandwich sichuan cucumber pickle, cool ranch aromatic pork & shrimp dumplings chicharone leeks, fish sauce, fried shallot whole duck roast in banana leaf green onion roti, eggplant sambal, pickle dungeness crab rice and noodles twice fried with chilis and tons of garlic, bakso noodle soup salted egg butter sauce, crispy cheung fun thin rice noodle, beef meatball, aromatic noodle roll, pickle, herbs broth, tomato, herbs, spicy shrimp sambal rice table char keow teow let us cook for you! the “rijsttafel” wok fried rice noodles, house chinese is a family-style feast centered around sausage, squid, shrimp, egg, garlic chives oma’s aromatic rice, with a table full of our most delicious dishes, sides, curries -

Menu 6.30 P.M

. Heritage Classics Set Lunch 2 - course at S$32* per person 3 - course at S$35* per person with Pear, Cashew Nut and Honey Ginger Dressing Thai-style Chicken Wing Sweet Chili Gastrique Green Mango Slaw with Sous Vide Egg and Somen in Pork Broth with Cincalok Shallot Relish and Fragrant Jasmine Rice with Wok Fried Garlic Maitake Mushroom, Bak Choy and Onsen Tamago with Lychee Ice Cream with Warm Chocolate and Gula Melaka Ice Cream *Prices are subject to service charge and prevailing government taxes Add-on your Favourite Signature Dishes Below Option as Main Butter Poached Half Lobster, Light Mayo and Chives in a Brioche Bun with Truffle Fries Broiled Miso-sake Marinated Black Cod Sarawak Pepper, Persillade Bearnaise and Truffle Fries… Kopi O Ice Cream Pandan Ice Cream Teh Tarik Ice Cream Pier Garden Salad Wok Fried Carrot Cake with Egg Vegetarian Fried Rice Assortment of Seasonal Fresh Fruits *Prices are subject to service charge and prevailing government taxes . (1) Heritage Dim Sum Brunch at The Clifford Pier . Harking back to the vibrant scenes of the landmark's glorious past, The Clifford Pier debuts a Heritage Dim Sum Brunch with Traditional Trolleys and love "Hawkers" stalls. — per adult . — per child (from 6 to 11 years old) Free flowing of Soft Drinks, Chilled Juices and Fullerton Bay Blend of Coffee and Tea Add $10.00* per person Free flowing of House Pour Wines, Sparkling Wines, Beers, Soft Drinks, Chilled Juices and Fullerton Bay Blend of Coffee and Tea Add $50.00* per person Salads Roasted Duck Salad with Fresh Sprouts -

Entree Beverages

Beverages Entree HOT/ COLD MOCKTAIL • Sambal Ikan Bilis Kacang $ 6 Spicy anchovies with peanuts $ 4.5 • Longing for Longan $ 7 • Teh Tarik longan, lychee jelly and lemon zest $ 4.5 • Kopi Tarik $ 7 • Spring Rolls $ 6.5 • Milo $ 4.5 • Rambutan Rocks rambutan, coconut jelly and rose syrup Vegetables wrapped in popia skin. (4 pieces) • Teh O $ 3.5 • Mango Madness $ 7 • Kopi O $ 3.5 mango, green apple and coconut jelly $ 6.5 • Tropical Crush $ 7 • Samosa pineapple, orange and lime zest Curry potato wrapped in popia skin. (5 pieces) COLD • Coconut Craze $ 7 coconut juice and pulp, with milk and vanilla ice cream • Satay $ 10 • 3 Layered Tea $ 6 black tea layered with palm sugar and Chicken or Beef skewers served with nasi impit (compressed rice), cucumber, evaporated milk onions and homemade peanut sauce. (4 sticks) • Root Beer Float $ 6 FRESH JUICE sarsaparilla with ice cream $ 10 $ 6 • Tauhu Sumbat • Soya Bean Cincau $5.5 • Apple Juice A popular street snack. Fresh crispy vegetables stuff in golden deep fried tofu. soya bean milk served with grass jelly • Orange Juice $ 6 • Teh O Ais Limau $ 5 • Carrot Juice $ 6 ice lemon tea $ 6 • Watermelon Juice $ 12 $ 5 • Kerabu Apple • freshAir Kelapa coconut juice Muda with pulp Crisp green apple salad tossed in mild sweet and sour dressing served with deep $ 5 fried chicken. • Sirap Bandung Muar rose syrup with milk and cream soda COFFEE $ 5 • Dinosaur Milo $ 12 malaysian favourite choco-malt drink • Beef Noodle Salad $ 4.5 Noodle salad tossed in mild sweet and sour dressing served with marinated beef. -

Entrée Sides Desserts

Entrée A. Satay Chicken Skewer 沙嗲鸡串 () . A. Vegetarian Spring Roll 素春卷 () . A. Minced Pork Spring Roll 猪肉春卷 () . A. Salt & Pepper Chicken Wings 椒盐鸡翅 () . A. Salt & Pepper Squid 椒盐鱿鱼 () . A. Spicy Salt & Pepper Squid 辣鱿鱼条 () . A. Mini Edamame Roll 毛豆卷 () . A. Deep Fried Prawn Dumplings 炸虾饺 () . A. Deep Fried Tofu 炸豆腐 () . Sides Steamed Rice 白饭 . Roti Place was 油饭 . Hainanese Steamed Rice opened in 2015 by a Coconut Rice 椰酱饭 . Malaysian craving a taste of Noodles 面条 . home. We want to share the flavours of You-tiao (Deep Fried Bread Stick) 油条 . Malaysia to the people of Brisbane through Deep Fried Mantou (Chinese Bun) 炸馒头 . our food. We proudly offer authentic Malaysian Steamed Vegetable 油菜 . street food favourites such as Roti Canai, Nasi Lemak, and Char Kuey Teow. As well as iconic Malaysian dishes Bak Kut Teh (Pork tea), Hainanese Chicken and Malaysian Kam Heong crab, which is wild caught from the Gold Coast. Desserts From humble street food beginnings, our signature roti is freshly F. Sago Pudding 西米布丁 . prepared in house daily and can be seen flipped to order in our open roti Pandan infused sago pudding with coconut kitchen. Roti is crispy, flakey flatbread served both savoury and sweet cream and coconut sugar syrup. and is a favourite for all Malaysians. Try our iconic Roti Canai for a F. Cendol Sundae 珍多新地 . Vanillia ice cream and Malaysian cendol jelly savoury option or our popular Mount Roti topped with condensed milk served with palm sugar syrup and crushed for something sweet. Our menu is ideal for sharing family style, just like MENU peanuts. -

Healthy Food Traditions of Asia: Exploratory Case Studies From

Harmayani et al. Journal of Ethnic Foods (2019) 6:1 Journal of Ethnic Foods https://doi.org/10.1186/s42779-019-0002-x ORIGINALARTICLE Open Access Healthy food traditions of Asia: exploratory case studies from Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia, and Nepal Eni Harmayani1, Anil Kumar Anal2, Santad Wichienchot3, Rajeev Bhat4, Murdijati Gardjito1, Umar Santoso1, Sunisa Siripongvutikorn5, Jindaporn Puripaatanavong6 and Unnikrishnan Payyappallimana7* Abstract Asia represents rich traditional dietary diversity. The rapid diet transition in the region is leading to a high prevalence of non-communicable diseases. The aim of this exploratory study was to document traditional foods and beverages and associated traditional knowledge that have potential positive health impacts, from selected countries in the region. The study also focused on identifying their importance in the prevention and management of lifestyle-related diseases and nutritional deficiencies as well as for the improvement of the overall health and wellbeing. This was conducted in selected locations in Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Nepal through a qualitative method with a pre-tested documentation format. Through a detailed documentation of their health benefits, the study tries to highlight the significance of traditional foods in public health as well as their relevance to local market economies towards sustainable production and consumption and sustainable community livelihoods. Keywords: Traditional foods, Ethnic recipes, Asian health food traditions, Cultural dietary diversity, Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Nepal Introduction Due to the dynamic adaptations to local biocultural con- Asia represents vast geographic, socioeconomic, bio- texts and refinement over generations through empirical logical, and cultural diversity. This is also reflected in the observations, they assume to have positive health impacts dietary diversity of traditional foods. -

MALAYSIAN ‘HAWKER’ STREET FOOD Hawker Centre in Malaysia Is an Open-Air Area Where Venders Come Together & Serve Their Specialty Dishes to the Public

MALAYSIAN ‘HAWKER’ STREET FOOD Hawker centre in Malaysia is an open-air area where venders come together & serve their specialty dishes to the public. We ofer both ‘makan’ (eat here) or ‘bungkus’ (take away.) OUR FAVOURITES Traditonal “Satay” Chicken £9.90 “ROTI CANAI” Char-grilled satay served with spicy peanut sauce, cucumber & onion Indian infuenced fatbread, the original street food served on the “Mamak Stalls” in the cites & The Legendary Malaysian villages in Malaysia. Rot Canai is served with “Beef Rendang” £10.50 curry, stufed or as a sweet dish. Braised beef cooked with lemongrass, galangal, toasted grated coconut, coconut milk & turmeric leaves Flufy Malaysian fat breads pan-fried & served with a tradi- tonal curry Curry Chicken £9.50 “Ayam Goreng Rempah” Fried Spiced Chicken £9.50 Curry Lamb £10.50 Fried chicken marinated in aromatc home blend spices paste Curry Seabass £9.50 (Vegetarian) Dhal Curry £6.50 LOCAL MALAYSIAN RICE & NOODLES “Nasi Lemak” Fragrant Coconut Rice £13.50 SIDE DISHES Steamed coconut rice served with aromatc fried chicken OR our succulent Legendary beef rendang, roasted peanuts, cu- cumber, anchovies, hard boiled egg & onion sambal paste Rot Canai 1pc £1.80 “Nasi Goreng Sambal” Steamed Coconut Rice £3.00 Spicy Fried Rice £13.50 Steamed White Rice £2.20 Str fried rice with sambal paste, egg, long beans, bird eye chilli, prawns, squid & chicken satay Vegetable Dumplings x 4 £6 “Mee Goreng Mamak” Chicken Dumplings x 4 £6 Spicy Fried Egg Noodles £12.50 Vegetable Spring Rolls £6 Str fried egg noodles with sambal paste, tomato, bean curd, bean sprouts, fsh cake, squid & prawns Please don’t hesitate to ask our team if you have any “Char Kuey Teow” dietary requirements. -

Kuaghjpteresalacartemenu.Pdf

Thoughtfully Sourced Carefully Served At Hyatt, we want to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising what’s best for future generations. We have a responsibility to ensure that every one of our dishes is thoughtfully sourced and carefully served. Look out for this symbol on responsibly sourced seafood certified by either MSC, ASC, BAP or WWF. “Sustainable” - Pertaining to a system that maintains its own viability by using techniques that allow for continual reuse. This is a lifestyle that will inevitably inspire change in the way we eat and every choice we make. Empower yourself and others to make the right choices. KAYA & BUTTER TOAST appetiser & soup V Tauhu sambal kicap 24 Cucumber, sprout, carrot, sweet turnip, chili soy sauce Rojak buah 25 Vegetable, fruit, shrimp paste, peanut, sesame seeds S Popiah 25 Fresh spring roll, braised turnip, prawn, boiled egg, peanut Herbal double-boiled Chinese soup 32 Chicken, wolfberry, ginseng, dried yam Sup ekor 38 Malay-style oxtail soup, potato, carrot toasties & sandwich S Kaya & butter toast 23 White toast, kaya jam, butter Paneer toastie 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, sour dough bread S Roti John JP teres 36 Milk bread, egg, chicken, chili sauce, shallot, coriander, garlic JPt chicken tikka sandwich 35 Onion, tomato, mayo, lettuce, egg JPt Black Angus beef burger 68 Coleslaw, tomato, onion, cheese, lettuce S Signature dish V Vegetarian Prices quoted are in MYR and inclusive of 10% service charge and 6% service tax. noodles S Curry laksa 53 Yellow noodle, tofu, shrimp, -

Grand Cafe a La Carte Menu

VEGETARIAN SANDWICHES 140 OSENG SAYURAN 80 CLUB SANDWICH Stir fried green vegetables, ginger and garlic Grilled chicken breast, fried egg, tomato, beef bacon, French fries PEPES TAHU 60 BEEF BURGER Steamed tofu in banana leaf, lemongrass, kemangi leaves Cheddar, beef bacon, lettuce, onion, pickles, French fries TEMPE MENDOAN 60 SMOKED SALMON SANDWICH Fried soybean cake, green onion, coriander, turmeric, sweet soy Toasted baguette, shredded romaine, sour cream, French fries SIGNATURES RUJAK 80 Local fruits, tamarind-peanut dressing MEAT AYAM WOKU 140 TONGSENG KAMBING 250 WOK FRIED BEEF 280 GADO-GADO 80 Chicken stew, chili, lime, turmeric, Cabbage, tomato, tamarind, Bell peppers, onion, black pepper Boiled puncak vegetables, spicy bogor peanut sauce pandan, kemangi leaves lemongrass, chili sauce LUMPIA SAYUR 80 Fried vegetable spring rolls, spicy peanut dip SOUP FROM PASTA 140 SOP BUNTUT 180 SOTO AYAM 120 THE GRILL SPAGHETTI BOLOGNESE Oxtail in clear beef soup, puncak vegetables, local spices Chicken and glass noodle soup, turmeric, Norwegian salmon 200g 320 Beef ragout, tomatoes, rosemary AYAM BAKAR YOGYA 140 egg, vegetables Grilled chicken, sweet soy, coriander, sambal Supreme chicken breast 200g 280 FUSILLI ALFREDO LONTONG CAP GOMEH 150 Smoked chicken, green pea, parmesan cheese NASI GORENG 140 Rice cake, chicken, coconut milk, Beef tenderloin 200g 450 Fried cianjur rice, prawns, chicken, fried egg, chicken satay chayote, hot spicy potato beef liver, PENNE ALLA NORMA RENDANG DAGING 150 hard-boiled pindang egg With your choice of: steamed -

Dpg Menu Pkp

MENU PKP 2 . 0 MASA : 11.OO am - 7.30 pm Jalan Baru Penanti Bandar Perda Permatang Pasir Guar Perahu Kubang Semang Permatang Pauh Tanah Liat Mengkuang Seberang Jaya 0 1 9 - 4 5 6 1 6 1 8 0 1 9 - 4 7 7 1 6 1 8 0 1 4 - 5 1 9 1 6 1 8 De Pauh Garden Restaurant Oficial Set Claypot Set Ayam Goreng RM 12.90 Set Ayam Goreng Kampung RM 13.90 Set Bawal Goreng RM 12.90 Set Keli Goreng RM 12.90 Set Kari Bawal RM 12.90 Set Kari Pari RM 12.90 Set Asam Pedas Pari RM 12.90 Set Asam Pindang Tongkol RM 11.90 Set Singgang RM 11.90 Set Ayam Penyet RM 14.90 Set Kari Kepala Ikan Set Claypot A Set Claypot B (1-2 pax) (3-4 pax) RM 75.00 RM 135.00 Nasi Putih Kari Kepala Ikan Ayam Goreng Sambal Sotong Sayur Kailan / Kangkung Telur Masin & Telur Dadar Sambal Belacan & Ulaman Jus Epal / Tembikai / Oren Set Thai Set Thai A Masakan Ikan Siakap / Jenahak (1-2 pax) RM 75.00 Pilihan Tomyam Pilihan Sayur Telur Dadar Set Thai B Nasi Putih (3-4 pax) Jus Epal / Tembikai / Oren RM 135.00 ALA THAI Pilihan Ikan Siakap Masak Tiga Rasa RM 40.00 Masak Stim Limau RM 40.00 Jenahak Masak Tiga Rasa RM 50.00 Masak Stim Limau RM 50.00 Pilihan Sayur Kangkung Belacan RM 5.50 Kailan Ikan Masin RM 6.50 Telur (M) Telur Dadar RM 4.50 Aneka Mee Mee Goreng DPG RM 10.50 Kuey Teow Goreng DPG RM 10.50 Bihun Goreng DPG RM 10.50 Kuey Teow Kungfu RM 10.50 Mee Bandung RM 9.50 Bihun Sup RM 9.50 Tambahan Nasi Putih RM 2.00 Mee / Kuey Teow / Bihun RM 1.50 Nasi Goreng Nasi Goreng Cina RM 7.90 Nasi Goreng Ayam RM 9.90 Nasi Goreng Kampung RM 9.90 Nasi Goreng Ikan Masin RM 9.90 Nasi Goreng Belacan RM14.50 -

DARI DAPUR BONDA Menu Ramadan 2018

DARI DAPUR BONDA Menu Ramadan 2018 MENU 1 Pak Ngah - Ulam-Ulaman Pucuk Paku, Ubi, Ulam Raja, Ceylon, Pegaga, Timun, Tomato, Kubis, Terung, Jantung Pisang, Kacang Panjang and Kacang Botol Sambal-Sambal Melayu Sambal Belacan, Tempoyak, Cili Kicap, Budu, Cencaluk, Air Asam, Tomato Sauce, Chili Sauce, Sambal Cili Hijau, Sambal Cili Merah, Sambal Nenas, Sambal Manga Pak Andak – Pembuka Selera Gado-Gado Dengan Kuah Kacang / Rojak Pasembur Kerabu Pucuk Paku, Kerabu Daging Salai Bakar Kerabu Manga Ikan Bilis Acar Buah Telur Masin, Ikan Masin, Tenggiri, Sepat, Gelama Dan Pari Keropok Keropok Ikan, Keropok Udang, Keropok Sotong, Keropok Malinjo, Keropok Sayur & Papadom Pak Cik- Salad Bar Assorted Garden Green Lettuce with Dressing and Condiments German Potato Salad, Coleslaw & Tuna Pasta Assorted Cheese, Crackers, Dried Fruit and Nuts Pak Usu – Segar dari Lautan Prawn, Bamboo Clam, Green Mussel & Oyster Lemon Wedges, Tabasco, Plum Sauce & Goma Sauce Jajahan Dari Timur - Japanese - Action Stall Assorted Sushi, Maki Roll & Sashimi - Maguro, Salmon Trout & Octopus Pickle Ginger, Shoyu, Wasabi Jajahan Dari Timur -Teppanyaki Prawn & Chicken with Vegetables Pak Ateh -Soup Sup Tulang Rusuk Cream of Pumkin Soup Assorted Bread & Butter Ah Seng - Itik & Ayam - Action Stall Ayam Panggang & Itik Panggang Nasi Ayam & Sup Ayam Chili, Kicap, Halia & Timun Mak Usu - Noodles Counter -Action Stall Mee Rebus, Clear Chicken Soup & Nonya Curry Laksa Dim Sum Assorted Dim Sum with Hoisin Sauce, Sweet Chilli & Thai Chilli Pak Uda - Ikan Bakar- Action Stall Ikan Pari, Ikan -

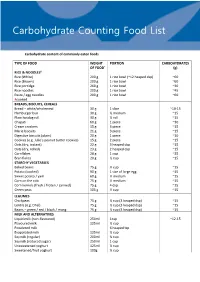

Carbohydrate Counting List

Tr45 Carbohydrate Counting Food List Carbohydrate content of commonly eaten foods TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF FOOD* (g) RICE & NOODLES# Rice (White) 200 g 1 rice bowl (~12 heaped dsp) ~60 Rice (Brown) 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 Rice porridge 260 g 1 rice bowl ~30 Rice noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~45 Pasta / egg noodles 200 g 1 rice bowl ~60 #cooked BREADS, BISCUITS, CEREALS Bread – white/wholemeal 30 g 1 slice ~10-15 Hamburger bun 30 g ½ medium ~15 Plain hotdog roll 30 g ½ roll ~15 Chapati 60 g 1 piece ~30 Cream crackers 15 g 3 piece ~15 Marie biscuits 21 g 3 piece ~15 Digestive biscuits (plain) 20 g 1 piece ~10 Cookies (e.g. Julie’s peanut butter cookies) 15 g 2 piece ~15 Oats (dry, instant) 22 g 3 heaped dsp ~15 Oats (dry, rolled) 23 g 2 heaped dsp ~15 Cornflakes 28 g 1 cup ~25 Bran flakes 20 g ½ cup ~15 STARCHY VEGETABLES Baked beans 75 g ⅓ cup ~15 Potato (cooked) 90 g 1 size of large egg ~15 Sweet potato / yam 60 g ½ medium ~15 Corn on the cob 75 g ½ medium ~15 Corn kernels (fresh / frozen / canned) 75 g 4 dsp ~15 Green peas 105 g ½ cup ~15 LEGUMES Chickpeas 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Lentils (e.g. Dhal) 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 Beans – green / red / black / mung 75 g ½ cup (3 heaped dsp) ~15 MILK AND ALTERNATIVES Liquid milk (non-flavoured) 250ml 1cup ~12-15 Flavoured milk 125ml ½ cup Powdered milk 6 heaped tsp Evaporated milk 125ml ½ cup Soymilk (regular) 200ml ¾ cup Soymilk (reduced sugar) 250ml 1 cup Unsweetened yoghurt 125ml ½ cup Sweetened/fruit yoghurt 100g ⅓ cup TYPE OF FOOD WEIGHT PORTION CARBOHYDRATES OF