Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sephardi Berberisca Dress, Tradition and Symbology

37 OPEN SOURCE LANGUAGE VERSION > ESPAÑOL The Sephardi Berberisca Dress, Tradition and Symbology by José Luís Sánchez Sánchez , Bachelor’s degree in Fine Arts and PhD from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid 1 This is an Arab tradition When the Jews were expelled from Spain in 1492 by the Catholic Monarchs, that was adopted by the many of them crossed the Strait of Gibraltar and put themselves under the Jews. Arabs and Berbers attribute a power of healing protection of the Sultan of Morocco, who at the time held court in Fez. This and protection to the henna meant that the Jewish people already living in North Africa, who were either plant and its leaves are used Arabic or Berber in their language and culture, were now joined by Sephardi for aesthetic and healing purposes. On the henna night, Jews from the Iberian Peninsula who held onto Spanish as their language of women paint their hands daily life and kept many of the customs and traditions developed over centuries following an Arab practice back in their beloved Sepharad. The clothing of the Sephardim, too, had its that is supposed to bring luck. own character, which was based on their pre-expulsion Spanish roots and now GOLDENBERG, André. Les Juifs du Maroc: images et changed slowly under the influence of their new Arab surroundings. textes. Paris, 1992, p. 114. The Sephardi berberisca dress, which is also known as el-keswa el-kbira in Arabic and grande robe in French (both meaning “great dress” in English), forms part of the traditional costume of Sephardi brides in northern Morocco. -

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004

A Century of Scholarship 1881 – 2004 Distinguished Scholars Reception Program (Date – TBD) Preface A HUNDRED YEARS OF SCHOLARSHIP AND RESEARCH AT MARQUETTE UNIVERSITY DISTINGUISHED SCHOLARS’ RECEPTION (DATE – TBD) At today’s reception we celebrate the outstanding accomplishments, excluding scholarship and creativity of Marquette remarkable records in many non-scholarly faculty, staff and alumni throughout the pursuits. It is noted that the careers of last century, and we eagerly anticipate the some alumni have been recognized more coming century. From what you read in fully over the years through various this booklet, who can imagine the scope Alumni Association awards. and importance of the work Marquette people will do during the coming hundred Given limitations, it is likely that some years? deserving individuals have been omitted and others have incomplete or incorrect In addition, this gathering honors the citations in the program listing. Apologies recipient of the Lawrence G. Haggerty are extended to anyone whose work has Faculty Award for Research Excellence, not been properly recognized; just as as well as recognizing the prestigious prize scholarship is a work always in progress, and the man for whom it is named. so is the compilation of a list like the one Presented for the first time in the year that follows. To improve the 2000, the award has come to be regarded completeness and correctness of the as a distinguishing mark of faculty listing, you are invited to submit to the excellence in research and scholarship. Graduate School the names of individuals and titles of works and honors that have This program lists much of the published been omitted or wrongly cited so that scholarship, grant awards, and major additions and changes can be made to the honors and distinctions among database. -

The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889-20151

The Life-Cycle of the Barcelona Automobile-Industry Cluster, 1889-20151 • JORDI CATALAN Universitat de Barcelona The life cycle of a cluster: some hypotheses Authors such as G. M. P. Swann and E. Bergman have defended the hy- pothesis that clusters have a life cycle.2 During their early history, clusters ben- efit from positive feedback such as strong local suppliers and customers, a pool of specialized labor, shared infrastructures and information externali- ties. However, as clusters mature, they face growing competition in input mar- kets such as real estate and labor, congestion in the use of infrastructures, and some sclerosis in innovation. These advantages and disadvantages combine to create the long-term cycle. In the automobile industry, this interpretation can explain the rise and decline of clusters such as Detroit in the United States or the West Midlands in Britain.3 The objective of this paper is to analyze the life cycle of the Barcelona au- tomobile- industry cluster from its origins at the end of the nineteenth centu- ry to today. The Barcelona district remained at the top of the Iberian auto- mobile clusters for a century. In 2000, when Spain had reached sixth position 1. Earlier versions of this paper were presented at the International Conference of Au- tomotive History (Philadelphia 2012), the 16th World Economic History Congress (Stellen- bosch 2012), and the 3rd Economic History Congress of Latin America (Bariloche 2012). I would like to thank the participants in the former meetings for their comments and sugges- tions. This research benefitted from the financial support of the Spanish Ministry of Econo- my (MINECO) and the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) through the projects HAR2012-33298 (Cycles and industrial development in the economic history of Spain) and HAR2015-64769-P (Industrial crisis and productive recovery in the Spanish history). -

WINE TOUR: ANDALUCIA in a GLASS (Small Exclusive Group Tour 4-12 People)

Escorted Tours in Andalusia WINE TOUR: ANDALUCIA IN A GLASS (Small exclusive group tour 4-12 people) Whether you are a seasoned fine wine aficionado or simply a lover of the grape looking to enjoy and better your knowledge of it, Andalusia is definitely the place for you! Wine in Andalusia has come a long way since 1100 BC when the Phoenicians first planted their vineyards in the fertile lands of Cadiz. By Roman times, wine was being produced in Andalusia in a big way and interestingly enough, this continued through Moorish times; despite the fact that the Koran frowns on the consumption of alcohol, some found creative ways to interpret the Koran’s words on wine, providing some justification such as medicinal purposes. From the 15th century onwards, Andalusian wines were shipped to appreciative drinkers elsewhere in Europe, particularly England, where there was a great fondness for Sack (as Sherry was called then) and sweet wines from Malaga. This happy situation prevailed until the 19th century when European vineyards were affected by the Oidium fungus (Powdery Mildew), followed by an even more devastating plague of Phylloxera (American vine root louse) which first appeared in Bordeaux in 1868 and spread to South Spain 20 years later. As a result, vineyards were replanted with plague-resistant American rootstock, while some, sadly, never fully recovered... From the historic sherries of Jerez, to the up-and-coming new vineyards in Ronda and Granada province, Andalusia boasts numerous top-quality wines. There are over 40.000 hectares of vineyards planted in 20 regions with over half of the wine production concentrated over 4 major ‘Denominación de Origen’ (D.O. -

San Roque San Roque

english español San Roque San Roque Ubicada en lo alto de un mirador atlántica, es una auténtica ma- Situated high on a natural vantage which are the Pinar del Rey forest natural, entre el Mar Mediterráneo ravilla ecológica que tiene en el point, between the Mediterranean and the Guadiaro River Estuary . The y la Bahía de Algeciras, la ciudad Pinar del Rey y el Estuario del río Sea and the Bay of Algeciras, the former, a 338-hectare forest, hou- gaditana de San Roque es conoci- Guadiaro sus máximos exponen- Cadiz city of San Roque is offi- ses a great variety of vegetation and da como la "Ciudad donde reside tes. El primero, un terreno de cially called the "City of Gibraltar wildlife and is currently the most la de Gibraltar", ya que fue funda- 338 hectáreas que alberga una in Exile", due to the fact it was frequently visited natural recreatio- San Roque San da por los gibraltareños que recha- gran variedad de flora y fauna, founded by the Spanish Gibralta- nal area in the municipality, thanks San Roque San zaron la oferta británica de que- constituye en la actualidad uno rians who rejected to stay under to its facilities and the nature trails darse en sus casas y se instalaron de los espacios recreativos natu- British rule, leaving in mass. They available. The River Guadiaro Es- en torno a la Ermita de San Roque rales más visitados de la comar- settled on a hill where the Saint tuary, on the Mediterranean coast, para no someterse al dominio bri- ca por sus instalaciones y por la Roque Shrine was located, dating is a 27-hectare protected area in- tánico en 1704. -

The Spaniards & Their Country

' (. ' illit,;; !•' 1,1;, , !mii;t( ';•'';• TIE SPANIARDS THEIR COUNTRY. BY RICHARD FORD, AUTHOR OF THE HANDBOOK OF SPAIN. NEW EDITION, COMPLETE IN ONE VOLUME. NEW YORK: GEORGE P. PUTNAM, 155 BROADWAY. 1848. f^iii •X) -+- % HONOURABLE MRS. FORD, These pages, which she has been, so good as to peruse and approve of, are dedicated, in the hopes that other fair readers may follow her example, By her very affectionate Husband and Servant, Richard Ford. CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. PAOK. A General View of Spain—Isolation—King of the Spains—Castilian Precedence—Localism—Want of Union—Admiration of Spain—M. Thiers in Spain , . 1 CHAPTER II. The Geography of Spain—Zones—Mountains—The Pyrenees—The Gabacho, and French Politics . ... 7 CHAPTER in. The Rivers of Spain—Bridges—Navigation—The Ebro and Tagus . 23 CHAPTER IV. Divisions into Provinces—Ancient Demarcations—Modern Depart- ments—Population—Revenue—Spanish Stocks .... 30 CHAPTER V. Travelling in Spain—Steamers—Roads, Roman, Monastic, and Royal —Modern Railway—English Speculations 40 CHAPTER VI. Post Office in Spain—Travelling with Post Horses—Riding post—Mails and Diligences, Galeras, Coches de DoUeras, Drivers and Manner of Driving, and Oaths 53 CHAPTER VII. SpanishHorsea—Mules—Asses—Muleteers—Maragatos ... 69 — CONTENTS. CHAPTER VIII. PAGB. Riding Tour in Spain—Pleasures of it—Pedestrian Tour—Choice of Companions—Rules for a Riding Tour—Season of year—Day's • journey—Management of Horse ; his Feet ; Shoes General Hints 80 CHAPTER IX. The Rider's cos.tume—Alforjas : their contents—The Bota, and How to use it—Pig Skins and Borracha—Spanish Money—Onzas and smaller coins 94 CHAPTER X. -

Spain: New Emigration Policies Needed for an Emerging Diaspora

SPAIN: NEW EMIGRATION POLICIES NEEDED FOR AN EMERGING DIASPORA By Joaquín Arango TRANSATLANTIC COUNCIL ON MIGRATION SPAIN New Emigration Policies Needed for an Emerging Diaspora By Joaquín Arango March 2016 Acknowledgments This research was commissioned by the Transatlantic Council on Migration, an initiative of the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), for its twelfth plenary meeting, held in Lisbon. The meeting’s theme was “Rethinking Emigration: A Lost Generation or a New Era of Mobility?” and this report was among those that informed the Council’s discussions. The Council is a unique deliberative body that examines vital policy issues and informs migration policymaking processes in North America and Europe. The Council’s work is generously supported by the following foundations and governments: Open Society Foundations, Carnegie Corporation of New York, the Barrow Cadbury Trust, the Luso-American Development Foundation, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation, and the governments of Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden. For more on the Transatlantic Council on Migration, please visit: www.migrationpolicy. org/transatlantic. © 2016 Migration Policy Institute. All Rights Reserved. Cover Design: Danielle Tinker, MPI Typesetting: Liz Heimann, MPI No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Migration Policy Institute. A full- text PDF of this document is available for free download from www.migrationpolicy. org. Information for reproducing excerpts from this report can be found at www. migrationpolicy.org/about/copyright-policy. Inquiries can also be directed to [email protected]. Suggested citation: Arango, Joaquín. -

Wine List Revised 2017.02.22

ARROYO VINO W I N E & SPIRITS LAST BOTTLE S (subject to availability) WHITES 1001 Colosi, Cataratto/Inzolia, Salina Bianco, Sicily, Italy, 2016 48 1002 Claude Riffault, Les Chassiegnes, Sancerre, France, 2018 66 1003 Domaine Anne Gros, Hautes-Côtes de Nuits, France, 2015 81 1004 Livio Felluga, Pinot Grigio, Collio, Italy, 2015 62 1005 Trimbach, Gewurztraminer, Alsace, France, 2015 54 1006 Cascina degli Ulivi, Cortese, Bellotti Bianco, Piedmont, 2017 (Sans soufre) 50 1007 Von Winning, Sauvignon Blanc, Pfalz, Germany, 2016 73 1008 Hiruzta, Hondarrabi Zuri, Getariako Txakolina, Spain, 2017 36 1009 Tolpuddle Vineyard, Chardonnay, Tasmania, Australia, 2017 93 1010 Daniel and Julien Barraud, Pouilly-Fuisse, France, 2013 60 1011 Domaine Billaud-Simon, Mont de Milieu, Chablis 1er Cru, France, 2016 102 1012 Veyder-Malberg, Riesling, Bruck, Wachau, Austria, 2015 (Dry) 110 REDS 3010 Saint Cosme, Syrah, Saint Joesph, France, 2016 88 3011 Donnafugata, Nero d’Avola, Sicily, Italy, 2017 46 3012 Rocca del Principe, Aglianico, Irpinia, Campania, Italy, 2011 44 3013 Hyde de Villaine, Pinot Noir, Sonoma Mountain, California, 2012 152 3014 A Tribute To Grace, Grenache, Vie Caprice, Santa Barbara, 2015 77 3015 Hyde de Villaine, Merlot/Cabernet Sauvignon, Napa Valley, 2012 105 3016 Les Lunes Wines, Carignan, Mendocino County, California, 2016 58 3017 Lioco, La Selva, Pinot Noir, Anderson Valley, 2015 71 3018 Recchia, Valpollicia Ripasso, Le Muriae, Veneto, Italy, 2007 38 3019 Neyers, Cabernet Sauvignon/Merlot, Napa Valley, 2016 65 3001 Curii Uvas y Vinos, -

XXI Cross Internacional De Italica Santiponce, 19 De Enero De 2003

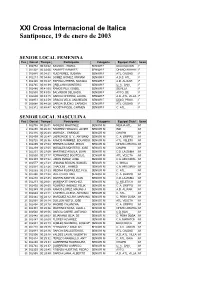

XXI Cross Internacional de Italica Santiponce, 19 de enero de 2003 SENIOR LOCAL FEMENINA Pos Dorsal Tiempo Participante Categoria Equipo/ Club/ Sexo 1 002752 00:34:02 BAUSAN ., ISABEL SENIOR F DELEGACIONColegio F 2 002302 00:34:06.37 RAMIREZ RAMIREZ, SENIOR F OHMIOPROV. DE ARAHAL ATL. F 3 002685 00:34:31.60 RUIZDOLORES PEREZ, SUSANA SENIOR F ATL. CIUDAD F 4 002213 00:34:44.16 GOMEZ GOMEZ, MIRIAM SENIOR F A.D.S.DE MOTRIL ATL. F 5 002346 00:35:27.28 ESPINO UTRERA, NATALIA SENIOR F A.D. ALIXAR F 6 002745 00:38:39.07 ORELLANA MONTERO, SENIOR F U. A . SAN F 7 002486 00:41:00.64 RAMOSELISA PILA, ISABEL SENIOR F SEVILLAFERNANDO F 8 002530 00:43:05.80 SALVADOR DELGADO, SENIOR F AYTO.ABIERTA DE F 9 002600 00:43:15.60 GARCIAROCIO CHORRO, LAURA SENIOR F A.D.CAZALLA ATL. VILLA F 10 000951 00:43:59.14 GRACIA VELA, ANA BELEN SENIOR F DELG.DE CABEZON PROV. F 11 002684 00:44:28.42 GARCIA BUENO, CARMEN SENIOR F ATL.DE JAN CIUDAD F 12 002312 00:45:47.30 ACOSTA POZO, CARMEN SENIOR F C.DE ATL. MOTRIL F .96 CHIPIONA SENIOR LOCAL MASCULINA Pos Dorsal Tiempo Participante Categoria Equipo/ Club/ Sexo 1 002735 00:26:01 ARNEDO MARTINEZ, SENIOR M NERJAColegio ATL. M 2 002268 00:26:38.19 RAMIREZGUILLERMO HIDALGO, JAVIER SENIOR M IND M 3 002316 00:26:40.08 MORAZA ., ENRIQUE SENIOR M CHAPIN M 4 002499 00:26:47.51 LADRON DE G. -

Porcentaje Sobre Volumen Presupuestario 2016

DESGLOSE PORCENTAJE SOBRE VOLUMEN PRESUPUESTARIO CONTRATOS MENORES IMPORTE IMPORTE Nª Nº NÚM. TIPO CRITERIO TRAMITE PROCEDIM. OBJETO ADJUDICATARIO LICITAC. ADJUDIC. PLAZO FECHA FECHA INV LIC (MESES) (ADJUDIC.) (FORMALI.) (I.V.A INC.) (I.V.A INC.) IBERICAR FORMULA MEJOR 3/2016 CÁDIZ, S.L. 25/10/2016 SUMINISTRO OFERTA ORDINARIO C MENOR 1 Furgoneta supervisión y trasporte personal - 4 13.519,02 13.519,02 1 - 228/2016 UNIPERSONAL D ECONÓMICA B-72.125.669 MEJOR 15/2016 Mantenimiento del ascensor CEIP Sagrado DUPLEX ELEVACIÓN, S.L. 09/09/2016 SERVICIO OFERTA ORDINARIO C MENOR 3 3 521,76 521,76 12 - 2623/2016 Corazón B-82.839.366 D ECONÓMICA TALLERES DIFUSIÓN MUSEO MUNICIPAL MEJOR “CARTEIA” A ESCOLARES PARA LA 24/2016 Sergio Galea Rodríguez, 18/04/2016 SERVICIO OFERTA ORDINARIO C MENOR DELEGACIÓN MUNICIPAL DE - 1 2.148,05 2.148,05 1 - 3148/2016 32.051.696-T D ECONÓMICA CULTURA DEL ILUSTRE AYUNTAMIENTO DE SAN ROQUE MEJOR 26/2016 Actividades de promoción tiempo libre, fomento ACORDE'SR 01/08/2016 SERVICIO OFERTA ORDINARIO C MENOR - 1 2200,00 2.200,00 1 - 3212/2016 artistas locales noveles G -72.059.025 D ECONÓMICA MEJOR 27/2016 Mantenimiento del ascensor de CEIP Santa Mª la DUPLEX ELEVACIÓN, S.L. 09/09/2016 SERVICIO OFERTA ORDINARIO C MENOR - 5 473,50 473,50 9 - 3283/2016 Coronada B-82.839.366 D ECONOMICA MEJOR CONSTRUCCIONES 37/2016 Adecuación de instalaciones deportivas en 14/06/2016 OBRA OFERTA ORDINARIO C MENOR 5 5 ROJAS CARRILLO, S.L. 39.501,56 33.335,00 1 - 4135/2016 campos de fútbol “A. -

C31a Die 15I V I L L $

~°rOV17 C31a die 15i V I L L $ Comprende esta provincia los siguientes Municipios por partidos judiciales . Partido de Carmona . Partido de Morán de la, Frontera. Campana (La) . AL-tirada del Alear . Algamitas . Morón de la Frontera . Coripe . r mona . Viso del Alcor (El) Pruna. Coronil (El) . Montellano . Puebla de Cazalla (La) . Partido de Cazalla de a Sierra . Partido de Osuna . Alarde . Na•,'a .s de la Concepció n Altuadén de la Plata . (Las) . Cazalla de le Sierra, 1'('dro .so (El) . Cunslantina, lleal de la . Jara (El) . Corrales (Los) . Rubio (El) . (Iemlalee ia , San Nieol ;ís del Puerto Lantejuela (La.) . Naucejo (BO . Martín (le la Jara . Osuna . Villanueve de San Juau . Partido de Écija. Partido de Sanlúcar la Mayor. Coija . ? .uieie(ia . (L,e fuentes de Andalucía . Alhaida de Aljarafe . Madroño (PIl} . Aznalcázar . Olivares . Aznalcóllar. Pilas. Partido de Estepa. IJenacazón . Ronquillo (El) . ('arrión de los Céspedes. Saltaras. Castilleja del Campo . Sanlúcar lal Mayor. Castillo de las Guarda s ITmbrete. Aguadulee . I Ferrera .. (El) . Villamanrique de la Con - Itadolatosa . Lora de Estepa, - Iüspartinas . lesa. Casariche, Marinaleda . ifuévar . Villanueva del Ariseal . Estepa . Pedrera, (Mena .. Roda ale Andalucía (Lo ) Partidos (cinco) de Sevilla . Partido de Lora del Río . Alardea del Río . Puebla de les. Infantes Alead -1 del Río . (La) . Gel ves . (°antillana . Algaba (La) . Tetina . Gerena Atmensilla . Gines ora del Río . Villanueva del 'Rfo . llollullos de la Mitación 1' ileflor . t'illaverde del Río . Guillada. llormujos . M-airena . del Aljarafe _ Tiranas . Palomares del Rfo . liurguillo .. Puebla del Río (La} . Camas. Rinconada (La) . Partido de Marchena . Castilblaneo de los Arro- San Juan de Azna1f- .,a s yos . -

Orientalisms the Construction of Imaginary of the Middle East and North Africa (1800-1956)

6 march 20 | 21 june 20 #IVAMOrientalismos #IVAMOrientalismes Orientalisms The construction of imaginary of the Middle East and North Africa (1800-1956) Francisco Iturrino González (Santander, 1864-Cagnes-sur-Mer, Francia, 1924) Odalisca, 1912. Óleo sobre lienzo, 91 x 139 cm Departament de Comunicació i Xarxes Socials [email protected] Departament de Comunicació i Xarxes Socials 2 [email protected] DOSSIER Curators: Rogelio López-Cuenca Sergio Rubira (IVAM Exhibitions and Collection Deputy Director) MªJesús Folch (assistant curator of the exhibition and curator of IVAM) THE EXHIBITION INCLUDES WORKS BY ARTISTS FROM MORE THAN 70 PUBLIC AND PRIVATE COLLECTIONS Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (National Calcography), Francisco Lamayer, César Álvarez Dumont, Antonio Muñoz Degrain (Prado Museum), José Benlliure (Benlliure House Museum), Joaquín Sorolla (Sorolla Museum of Madrid), Rafael Senet and Fernando Tirado (Museum of Fine Arts of Seville), Mariano Bertuchi and Eugenio Lucas Velázquez (National Museum of Romanticism), Marià Fortuny i Marsal (Reus Museum, Tarragona), Rafael de Penagos (Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid, Institut del Teatre de Barcelona, MAPFRE Collection), Leopoldo Sánchez (Museum of Arts and Customs of Seville), Ulpiano Checa (Ulpiano Checa Museum of Madrid), Antoni Fabrés (MNAC and Prado Museum), Emilio Sala y Francés and Joaquín Agrasot (Gravina Palace Fine Arts Museum, Alacant), Etienne Dinet and Azouaou Mammeri (Musée d’Orsay), José Ortiz Echagüe (Museum of the University of Navarra), José Cruz Herrera (Cruz Herrera