India's Limited War Doctrine: the Structural Factor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Share to Be Transferred to IEPF.Xlsx

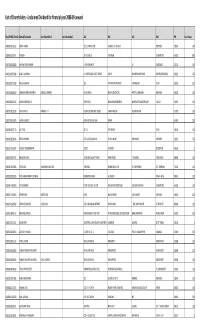

List of Shareholders ‐ Unclaimed Dividend for financial year 2008‐09 onward Folio/DP‐ID & Client ID Name of Shareholder Joint Shareholder 1 Joint Shareholder 2 AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 PIN No of shares IN30009510512622 SHANTI TOMAR 125, HUMAYUN PUR SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE NEW DELHI 110029 100 IN30009511023704 P SURESH 28 R R LAYOUT R S PURAM COIMBATORE 641001 1000 IN30011810558083 SHIV RAJ SINGH SHARMA V P.O. MAKANPUR UP GHAZIABAD 201010 100 IN30011810706380 NAND LAL MENANI C O KASTURI BAI COLD STORAGE HAPUR BULANDSHAHAR ROAD HAPUR (GHAZIABAD) 245101 100 IN30011810772083 RAHUL AGRAWAL 362 SITA RAM APARTMENTS PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 200 IN30011810804832 SARBINDER SINGH SAWHNEY HARLEEN SAWHNEY HOUSE NO 65 WEST AVENUE ROAD WEST PUNJABI BAGH NEW DELHI 110026 200 IN30011810878226 ASHOK KUMAR MALIK S/W 393/14 NEAR MAHABIR MANDIR MAIN BAZAR BAHADUR GARH JHAJJAR 124507 100 IN30017510122592 VIJI KANNAN. K KANNAN. K. R 4/146 A SECOND MAIN STREET SHANTHI NAGAR PALAYANKOTTAI 627002 100 IN30017510155076 SATISH KUMAR. D INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK ANNUR 641653 200 IN30020610257473 M L GOYAL QP ‐ 31 PITAMPURA DELHI 110034 100 IN30020610296246 DEEPAK SHARMA FLAT‐3, SOOD BUILDING TEL MILL MARG RAM NAGAR NEW DELHI 110055 700 IN30021413290147 GUDURU SUBRAMANYAM 10/471 K K STREET PRODDATUR 516360 1 IN30023910397325 BALAMURUGAN V 1073/133H, MILLAR PURAM ANNA NAGAR TUTUCORIN TAMIL NADU 628008 200 IN30026310156836 SUTAPA SEN SAMARESH KUMAR SEN TURI PARA DIGHIRPAR,N.C.PUR PO‐ RAMPURHAT DIST‐ BIRBHUM 731224 100 IN30034320058199 PATEL HARGOVANBHAI VELABHAI LIMDAWALO MADH JAL CHOWK -

Relilance Santa Cruz (E) Fax: +91 22 4303 1664 Mumbai 400 055 CIN: L75100MH1929PLC001530

Reliance Infrastructure Limited Reliance Centre Tel: +91 22 4303 1000 ReLIlANce Santa Cruz (E) Fax: +91 22 4303 1664 Mumbai 400 055 www.rinfra.com CIN: L75100MH1929PLC001530 October 9, 2019 SSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Limited Dalal Street, Exchange Plaza, 5th Floor, Mumbai 400 001 Plot No. C/1, G Block, SSE Scrip Code: 500390 Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai 400 051 NSE Scrip Symbol: RELINFRA Dear Sirs, Sub: Disclosure under Regulation 30 of SEBI (Listing Obligation and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations 2015 In terms of Regulation 30 of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 read with Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD/4/2015 dated September 9, 2015 issued by the Securities and Exchange Board of India, we make the disclosure as regards change in Directors of the Company in the prescribed format as attached. The Board hereby confirms that the Directors being appointed are not debarred from holding the office of director by virtue of any SEBI order or any other such authority. We also enclose herewith the media release in the given matter. Yours faithfully For Reliance Infrastructure Limited Paresh Rathod Company Secretary Ene!.: As above Registered Office: Reliance Centre, Ground Floor, 19, Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ballard Estate, Mumbai 400 001. ReLIJANce Annexure Information pursuant to Regulation 30 of Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements), Regulations, 2015 read with Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD/4/2015 dated September 9,2015 issued by SEBI 1. Reason for change: a. Appointment of Shri Jai Anmol Ambani and Shri Jai Anshul Ambani, as additional Directors on the Board of the Company in the capacity of Non Executive Directors, and b. -

14 Indian Navy

Indian Navy Module - IV Armed Forces Today 14 Note INDIAN NAVY The Indian Navy is the maritime arm of the Indian armed forces; it protects and secures the Indian maritime borders. It also protects Indian shipping in the Indian Ocean region. It is one of the world's largest Navies in terms of both personnel and naval vessels. India has a rich maritime heritage that dates back thousands of years. The beginning of India's maritime history dates back to 3000 BC. During this time, the inhabitants of Indus Valley Civilisation had maritime trade link with Mesopotamia. The discovery of a tidal dock at Lothal in Gujarat is proof of India's ancient maritime tradition. The mention of the Department of Navadhyaksha or Superindent of Ships in Kautilya's treatise Arthasastra highlights the development of maritime commerce. The ancient Tamil empire of the Cholas in the south, and the Marathas and the Zamorins of Kerala during the 16th and 17th centuries maintained naval fleets. You have read about all this in the previous lesson on 'Ancient Armies'. Objectives After studying this lesson, you will be able to: explain the origin and evolution of the Indian Navy; outline the role and responsibilities of the Indian Navy; indicate the organisational structure of the Indian Navy and identify the different branches of Indian Navy. 14.1 Origin and Evolution of Indian Navy (a) The history of the Indian Navy can be traced back to 1612 when Captain Best encountered and defeated the Portuguese. It was responsible for the protection of the East India Company's trade in the Gulf of Cambay and the river mouths of the Tapti and Narmada. -

City Coins Post Al Medal Auction No. 68 2017

Complete visual CITY COINS CITY CITY COINS POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION NO. 68 MEDAL POSTAL POSTAL Medal AUCTION 2017 68 POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 68 CLOSING DATE 1ST SEPTEMBER 2017 17.00 hrs. (S.A.) GROUND FLOOR TULBAGH CENTRE RYK TULBAGH SQUARE FORESHORE CAPE TOWN, 8001 SOUTH AFRICA P.O. BOX 156 SEA POINT, 8060 CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 425 2639 FAX: +27 21 425 3939 [email protected] • www.citycoins.com CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ELECTRONICALLY ON OUR WEBSITE INDEX PAGES PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 2 – 3 THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1880-1881 4 – 9 by ROBERT MITCHELL........................................................................................................................ ALPHABETICAL SURNAME INDEX ................................................................................ 114 PRICES REALISED – POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 67 .................................................... 121 . BIDDING GUIDELINES REVISED ........................................................................................ 124 CONDITIONS OF SALE REVISED ........................................................................................ 125 SECTION I LOTS THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE; MEDALS ............................................. 1 – 9 SOUTHERN AFRICAN VICTORIAN CAMPAIGN MEDALS ........................................ 10 – 18 THE ANGLO BOER WAR 1899-1902: – QUEEN’S SOUTH AFRICA MEDALS ............................................................................. -

Pakistan's Military Elite Paul Staniland University of Chicago Paul

Pakistan’s Military Elite Paul Staniland University of Chicago [email protected] Adnan Naseemullah King’s College London [email protected] Ahsan Butt George Mason University [email protected] DRAFT December 2017 Abstract: Pakistan’s Army is a very politically important organization. Yet its opacity has hindered academic research. We use open sources to construct unique new data on the backgrounds, careers, and post-retirement activities of post-1971 Corps Commanders and Directors-General of Inter-Services Intelligence. We provide evidence of bureaucratic predictability and professionalism while officers are in service. After retirement, we show little involvement in electoral politics but extensive involvement in military-linked corporations, state employment, and other positions of influence. This combination provides Pakistan’s military with an unusual blend of professional discipline internally and political power externally - even when not directly holding power. Acknowledgments: Michael Albertus, Jason Brownlee, Christopher Clary, Hamid Hussain, Sana Jaffrey, Mashail Malik, Asfandyar Mir, Vipin Narang, Dan Slater, and seminar participants at the University of Texas at Austin have provided valuable advice and feedback. Extraordinary research assistance was provided by Yusuf al-Jarani and Eyal Hanfling. 2 This paper examines the inner workings of Pakistan’s army, an organization central to questions of local, regional, and global stability. We investigate the organizational politics of the Pakistan Army using unique individual-level -

Armed Forces Tribunal, Regional Bench, Kochi O.A

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A.Nos. 70 of 2011 & 118 of 2013 FRIDAY, THE 21ST DAY OF NOVEMBER, 2014/30TH KARTHIKA, 1936 CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SHRIKANT TRIPATHI, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL M.P.MURALIDHARAN,AVSM & BAR, NM, MEMBER (A) O.A.NO.70 OF 2011: APPLICANT: JC-459291W EX-NB SUB CLK SAJEEV MOHAN K, AGED 45 YEARS, RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA-590 009. BY ADV.SRI.RAMESH.C.R. VERSUS RESPONDENTS: 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. 2. THE CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF, INTEGRATED HQRS. OF MOD (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. 3. THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, AG'S BRANCH, ARMY HEADQUARTERS, DHQ.P.O., NEW DELHI-110011. 4. THE GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING (WESTERN COMMAND), CNANDIMANDIR (UT), ARMY PIN CODE – 908543. O.A.70 of 2011 & 118 of 2013 - 2 - 5. THE GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING (HQR), 7 INF DIV, PIN – 908407, C/O.56 APO. 6. THE DIRECTOR, RECRUITING, ARMY RECRUITING OFFICE, FEROZPUR, PUNJAB, C/O.56 APO. 7. THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE, WESTERN COMMAND, IS GROUP, CHANDIMANDIR (UT) ARMY PIN 904992. 8. THE RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA-590 009. BY ADV.SRI.K.M.JAMALUDHEEN, SENIOR PANEL COUNSEL O.A.NO.118 OF 2013: APPLICANT: JC-459291W NB SUB CLK SAJEEV MOHAN K, AGED 43 YEARS, RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA-590 009. BY ADV.SRI.RAMESH.C.R. VERSUS RESPONDENTS: 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. -

Final-1-August-2021-3Rd-FHRJK-Report-AM.Pdf

i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Report and Methodology Executive Summary and Recommendations vi List of Rights that Continue to be Violated: 1 1. Civilian Security 10 2. Children, Women and Health 34 3. Land, Demography and Identity Rights 40 4. Industry and Employment 46 5. The Freedom of Media, Speech & Information 51 Conclusion 56 List of abbreviations 57 Appendix: About the Forum 58 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Forum for Human Rights in Jammu and Kashmir would like to express deep gratitude to Shivani Sanghavi, who drafted this Report, and to Amjad Majid for the layout. iii THE REPORT AND METHODOLOGY The Forum for Human Rights in Jammu and Kashmir comprises an informal group of concerned citizens who believe that, in the prevailing situation in the former state, an independent initiative is required so that continuing human rights violations do not go unnoticed. This is the third report issued by the Forum. It has largely been compiled from government sources, media accounts (carried in well-established and reputed newspapers or television), NGO fact-finding reports, interviews, and information garnered through legal petitions. The report relies primarily on information collected between 1 February 2021 and 23 July 2021. Though in situ verification has not been possible during the Covid-19 lockdown, the various sources listed above have been fact-checked against each other to ensure the information is as accurate as possible, and only that information has been carried that appears to be well-founded. Where there is any doubt regarding a piece of information, queries have been footnoted. [email protected] iv Members of the Forum Co-Chairs: Justice Madan B. -

Russian Influence on India's Military Doctrines

COMMENTARY Russian Influence on India’s Military Doctrines VIPIN NARANG espite a growing relationship since 2000 between the United States and India and various designations that each is a “strategic partner” or “major defense partner,” India’s three conventional services and increasingly its nuclear program—as it moves to sea—are largely dependent on another country D 1 for mainline military equipment, India’s historical friend: Russia. Since the 1970s, each of the conventional services has had a strong defense procurement relationship with Russia, who tends to worry less than the United States about transferring sensitive technologies. Currently, each of the services operates frontline equipment that is Russian— the Army with T-90 tanks, the Air Force with both MiGs and Su-30MKIs, and the Navy with a suite of nuclear-powered submarines (SSBN) and aircraft carri- ers that are either Russian or whose reactors were designed with Russian assis- tance. This creates a dependence on Russia for spare parts, maintenance, and training that outstrips any dependency India has for military equipment or op- erations. In peacetime, India’s force posture readiness is critically dependent on maintenance and spare parts from Russia. In a protracted conflict, moreover, Rus- sia could cripple India’s military services by withholding replacements and spares. This means India cannot realistically unwind its relationship with Moscow for at least decades, while these platforms continue to serve as the backbone of Indian military power. In terms of doctrine and strategy, although it may be difficult to trace direct influence and lineage between Russia and India, there are several pieces in India’s conventional and nuclear strategy that at least mirror Russia’s behavior. -

Biographies Introduction V4 0

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES An introduction to the Biographies of officers in the British Army and pre-partition Indian Army published on the web-site www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk, including: • Explanation of Terms, • Regular Army, Militia and Territorial Army, • Type and Status of Officers, • Rank Structure, • The Establishment, • Staff and Command Courses, • Appointments, • Awards and Honours. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 13 May 2020 [BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES] British Military History Biographies This web-site contains selected biographies of some senior officers of the British Army and Indian Army who achieved some distinction, notable achievement, or senior appointment during the Second World War. These biographies have been compiled from a variety of sources, which have then been subject to scrutiny and cross-checking. The main sources are:1 ➢ Who was Who, ➢ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ➢ British Library File L/MIL/14 Indian Army Officer’s Records, ➢ Various Army Lists from January 1930 to April 1946: http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=army%20list ➢ Half Year Army List published January 1942: http://www.archive.org/details/armylisthalfjan1942grea ➢ War Services of British Army Officers 1939-46 (Half Yearly Army List 1946), ➢ The London Gazette: http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/, ➢ Generals.dk http://www.generals.dk/, ➢ WWII Unit Histories http://www.unithistories.com/, ➢ Companions of The Distinguished Service Order 1923 – 2010 Army Awards by Doug V. P. HEARNS, C.D. ➢ Various published biographies, divisional histories, regimental and unit histories owned by the author. It has to be borne in mind that discrepancies between sources are inevitable. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

SUPPLEMENT to the LONDON GAZETTE, N MAY, 1937 3087 Captain Trevor Edward Palmer, M.B., Indian No

SUPPLEMENT TO THE LONDON GAZETTE, n MAY, 1937 3087 Captain Trevor Edward Palmer, M.B., Indian No. 6676002 Warrant Officer Class II, Regi- Medical Service, late Medical Officer, British mental Quarter-Master Sergeant Reginald Legation Guard, Addis Ababa, Abyssinia. George Callingham, i6th London Regiment Lieutenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel Edward (Queen's Westminster and Civil Service John William Porter, T.D., Hampshire Rifles), Territorial Army. Fortress -Engineers, Royal Engineers, Terri- No. 3303392 Warrant Officer Class II, Com- torial Army. pany Sergeant-Major Neil Campbell, gth Lieutenant-Colonel Henry Shapcott, M.C., (Glasgow Highlanders). Battalion, The High- Extra Regimentally Employed List, Military land Light Infantry'l(City of Glasgow Regi- Assistant, Military and Air Force Depaft- ment), Territorial Army. "ment, Office of the Judge Advocate General Warrant Officer Class I, Regimental Sergeant- of the Force. Major George Van Sanden Cooke, Ceylon Lieutenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel Ralph Garrison Artillery, Ceylon Defence Force. Cecil Seel, M.C., T.D., Royal Corps of Lieutenant (Assistant Commissary) Thomas Signals, Territorial Army. Couzens, Indian Army Corps of Clerks, Miss Elizabeth Dunlop Smaill, A.R.R.C., Indian Unattached List, Chief Clerk, Head- . Principal Matron, and Scottish General quarters, Western Command, India. Hospital, Territorial Army Nursing Service. Captain (Deputy Commissary) Viccars Crews, Major (Quarter-Master) Edward Francis Snape, Retired, late Indian Army Ordnance Corps. ist Battalion," The South Staffordshire Regi- No. 5097328 Warrant Officer Class II, Regi- ment. mental Quarter-Master-Sergeant Thomas Lieutenant-Colonel and Brevet Colonel Charles Charles Cross, 69th (The Royal Warwick- Beechey Spencer, T.D., late Territorial shire Regiment), Anti-Aircraft Brigade, Army. -

UP Police Constable Exam Paper – 28 January 2019 (First Shift)

www.examstocks.com https://t.me/sscplus UP Police Constable Exam Paper – 28 January 2019 (First Shift) The Handwritten Constitution Was Signed On 24th January, 1950, By 284 Members Of The Constituent Assembly, Which Included _________women. (A) 30 (B) 20 (C) 15 (D) 25 Answer -C The Kakori Train Robbery Was Conceived By Ram Prasad Bismil And ______ . (A) Khudiram Bose (B) Shivaram Rajguru (C) Ashfaqullah Khan (D) Jatindra Nath Das Answer -C “My Passage From India” Is A Book Written By _________. (A) Mulk Raj Anand (B) Edward Morgan Forster (C) Vidiadhar Surajprasad Naipaul (D) Ismail Mechant Answer -D _____is The O†Ȃcial Currency Of Finland. (A) Dollar (B) Pound (C) Rial (D) Euro Answer -D Who Invented The Jet Engine? (A) Roger Bacon (www.examstocks.comB) Sir Frank Whittle (C) James Watt fb.com/examstocksofficial https://t.me/examstocks www.examstocks.com https://t.me/sscplus (D) Lewis Edson Waterman Answer -B Name The Younger Son Of Shivaji Who Was Also The Third Chhatrapati. (A) Rajaram (B) Sambhaji (C) Shahu (D) Bajirao Answer -A Which Indian State Has Its Maximum Area Under Forest Cover? (A) Kerala (B) Maharashtra (C) Uttar Pradesh (D) Madhya Pradesh Answer -D Which Of The Following Is NOT A State Of The United States Of America? (A) New York (B) Minnesota (C) Louisiana (D) Atlanta Answer -D Which Line Demarcates The Boundary Between India And Pakistan? (A) McMahon Line (B) Redcliတāe Line (C) Madison Line (D) Durand Line Answer -B World Environment Day Is Held On Which Day? (www.examstocks.comA) 22nd April fb.com/examstocksofficial https://t.me/examstocks www.examstocks.com https://t.me/sscplus (B) 8th May (C) 5th June (D) 11th June Answer -C Which Of The Following Social Media Networks Is NOT A Publicly Listed Company? (A) Twitter (B) Facebook (C) Weibo (D) Quora Answer – Pyongyang Is The Capital Of Which Country? (A) Maldives (B) Mongolia (C) Malaysia (D) North Korea Answer -D _________ Is An Ancient Folk Dance Originating From Odisha.