Cold Start – Hot Stop? a Strategic Concern for Pakistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Share to Be Transferred to IEPF.Xlsx

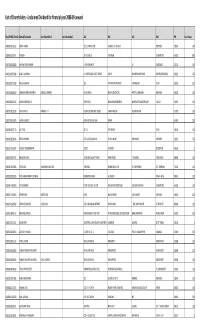

List of Shareholders ‐ Unclaimed Dividend for financial year 2008‐09 onward Folio/DP‐ID & Client ID Name of Shareholder Joint Shareholder 1 Joint Shareholder 2 AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 PIN No of shares IN30009510512622 SHANTI TOMAR 125, HUMAYUN PUR SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE NEW DELHI 110029 100 IN30009511023704 P SURESH 28 R R LAYOUT R S PURAM COIMBATORE 641001 1000 IN30011810558083 SHIV RAJ SINGH SHARMA V P.O. MAKANPUR UP GHAZIABAD 201010 100 IN30011810706380 NAND LAL MENANI C O KASTURI BAI COLD STORAGE HAPUR BULANDSHAHAR ROAD HAPUR (GHAZIABAD) 245101 100 IN30011810772083 RAHUL AGRAWAL 362 SITA RAM APARTMENTS PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 200 IN30011810804832 SARBINDER SINGH SAWHNEY HARLEEN SAWHNEY HOUSE NO 65 WEST AVENUE ROAD WEST PUNJABI BAGH NEW DELHI 110026 200 IN30011810878226 ASHOK KUMAR MALIK S/W 393/14 NEAR MAHABIR MANDIR MAIN BAZAR BAHADUR GARH JHAJJAR 124507 100 IN30017510122592 VIJI KANNAN. K KANNAN. K. R 4/146 A SECOND MAIN STREET SHANTHI NAGAR PALAYANKOTTAI 627002 100 IN30017510155076 SATISH KUMAR. D INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK ANNUR 641653 200 IN30020610257473 M L GOYAL QP ‐ 31 PITAMPURA DELHI 110034 100 IN30020610296246 DEEPAK SHARMA FLAT‐3, SOOD BUILDING TEL MILL MARG RAM NAGAR NEW DELHI 110055 700 IN30021413290147 GUDURU SUBRAMANYAM 10/471 K K STREET PRODDATUR 516360 1 IN30023910397325 BALAMURUGAN V 1073/133H, MILLAR PURAM ANNA NAGAR TUTUCORIN TAMIL NADU 628008 200 IN30026310156836 SUTAPA SEN SAMARESH KUMAR SEN TURI PARA DIGHIRPAR,N.C.PUR PO‐ RAMPURHAT DIST‐ BIRBHUM 731224 100 IN30034320058199 PATEL HARGOVANBHAI VELABHAI LIMDAWALO MADH JAL CHOWK -

India-Pakistan Conflict: Records of the Us State Department, February 1963

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICT: RECORDS OF THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT, FEBRUARY 1963-1966 Over 16,000 pages of State Department Central Files on India and Pakistan from 1963 through 1966 make this collection a standard documentary resource for the study of the political relations between India and Pakistan during a crucial period in the Cold War and the shifting alliances and alignments in South Asia. Date Range: 1963-1966 Content: 15,387 images Source Library: U.S. National Archives Detailed Description: Relations with Pakistan have demanded a high proportion of India’s international energies and undoubtedly will continue to do so. India and Pakistan have divergent national ideologies and have been unable to establish a mutually acceptable power equation in South Asia. The national ideologies of pluralism, democracy, and secularism for India and of Islam for Pakistan grew out of the pre-independence struggle between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, and in the early 1990s the line between domestic and foreign politics in India’s relations with Pakistan remained blurred. Because great-power competition—between the United States and the Soviet Union and between the Soviet Union and China—became intertwined with the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India was unable to attain its goal of insulating South Asia from global rivalries. This superpower involvement enabled Pakistan to use external force in the face of India’s superior endowments of population and resources. The most difficult problem in relations between India and Pakistan since partition in August 1947 has been their dispute over Kashmir. -

Relilance Santa Cruz (E) Fax: +91 22 4303 1664 Mumbai 400 055 CIN: L75100MH1929PLC001530

Reliance Infrastructure Limited Reliance Centre Tel: +91 22 4303 1000 ReLIlANce Santa Cruz (E) Fax: +91 22 4303 1664 Mumbai 400 055 www.rinfra.com CIN: L75100MH1929PLC001530 October 9, 2019 SSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Limited Dalal Street, Exchange Plaza, 5th Floor, Mumbai 400 001 Plot No. C/1, G Block, SSE Scrip Code: 500390 Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai 400 051 NSE Scrip Symbol: RELINFRA Dear Sirs, Sub: Disclosure under Regulation 30 of SEBI (Listing Obligation and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations 2015 In terms of Regulation 30 of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 read with Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD/4/2015 dated September 9, 2015 issued by the Securities and Exchange Board of India, we make the disclosure as regards change in Directors of the Company in the prescribed format as attached. The Board hereby confirms that the Directors being appointed are not debarred from holding the office of director by virtue of any SEBI order or any other such authority. We also enclose herewith the media release in the given matter. Yours faithfully For Reliance Infrastructure Limited Paresh Rathod Company Secretary Ene!.: As above Registered Office: Reliance Centre, Ground Floor, 19, Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ballard Estate, Mumbai 400 001. ReLIJANce Annexure Information pursuant to Regulation 30 of Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements), Regulations, 2015 read with Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD/4/2015 dated September 9,2015 issued by SEBI 1. Reason for change: a. Appointment of Shri Jai Anmol Ambani and Shri Jai Anshul Ambani, as additional Directors on the Board of the Company in the capacity of Non Executive Directors, and b. -

A Look Into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan Over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori

A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/07/a-look-into-the-conflict-between-india-and-pakistan-over-kashmir/ PRANAV ASOORI, OCT 7 2020 The region of Kashmir is one of the most volatile areas in the world. The nations of India and Pakistan have fiercely contested each other over Kashmir, fighting three major wars and two minor wars. It has gained immense international attention given the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers and this conflict represents a threat to global security. Historical Context To understand this conflict, it is essential to look back into the history of the area. In August of 1947, India and Pakistan were on the cusp of independence from the British. The British, led by the then Governor-General Louis Mountbatten, divided the British India empire into the states of India and Pakistan. The British India Empire was made up of multiple princely states (states that were allegiant to the British but headed by a monarch) along with states directly headed by the British. At the time of the partition, princely states had the right to choose whether they were to cede to India or Pakistan. To quote Mountbatten, “Typically, geographical circumstance and collective interests, et cetera will be the components to be considered[1]. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

City Coins Post Al Medal Auction No. 68 2017

Complete visual CITY COINS CITY CITY COINS POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION NO. 68 MEDAL POSTAL POSTAL Medal AUCTION 2017 68 POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 68 CLOSING DATE 1ST SEPTEMBER 2017 17.00 hrs. (S.A.) GROUND FLOOR TULBAGH CENTRE RYK TULBAGH SQUARE FORESHORE CAPE TOWN, 8001 SOUTH AFRICA P.O. BOX 156 SEA POINT, 8060 CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 425 2639 FAX: +27 21 425 3939 [email protected] • www.citycoins.com CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ELECTRONICALLY ON OUR WEBSITE INDEX PAGES PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 2 – 3 THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1880-1881 4 – 9 by ROBERT MITCHELL........................................................................................................................ ALPHABETICAL SURNAME INDEX ................................................................................ 114 PRICES REALISED – POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 67 .................................................... 121 . BIDDING GUIDELINES REVISED ........................................................................................ 124 CONDITIONS OF SALE REVISED ........................................................................................ 125 SECTION I LOTS THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE; MEDALS ............................................. 1 – 9 SOUTHERN AFRICAN VICTORIAN CAMPAIGN MEDALS ........................................ 10 – 18 THE ANGLO BOER WAR 1899-1902: – QUEEN’S SOUTH AFRICA MEDALS ............................................................................. -

India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute Asian Studies Institute & Centre for Strategic Studies Rajat Ganguly ISSN: 11745991 ISBN: 0475110552

Asian Studies Institute Victoria University of Wellington 610 von Zedlitz Building Kelburn, Wellington 04 463 5098 [email protected] www.vuw.ac.nz/asianstudies India, Pakistan and the Kashmir Dispute Asian Studies Institute & Centre for Strategic Studies Rajat Ganguly ISSN: 11745991 ISBN: 0475110552 Abstract The root cause of instability and hostility in South Asia stems from the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. It has led to two major wars and several near misses in the past. Since the early 1990s, a 'proxy war' has developed between India and Pakistan over Kashmir. The onset of the proxy war has brought bilateral relations between the two states to its nadir and contributed directly to the overt nuclearisation of South Asia in 1998. It has further undermined the prospects for regional integration and raised fears of a deadly IndoPakistan nuclear exchange in the future. Resolving the Kashmir dispute has thus never acquired more urgency than it has today. This paper analyses the origins of the Kashmir dispute, its influence on IndoPakistan relations, and the prospects for its resolution. Introduction The root cause of instability and hostility in South Asia stems from the unresolved nature of the Kashmir dispute between India and Pakistan. In the past fifty years, the two sides have fought three conventional wars (two directly over Kashmir) and came close to war on several occasions. For the past ten years, they have been locked in a 'proxy war' in Kashmir which shows little signs of abatement. It has already claimed over 10,000 lives and perhaps irreparably ruined the 'Paradise on Earth'. -

Kashmir Conflict: a Critical Analysis

Society & Change Vol. VI, No. 3, July-September 2012 ISSN :1997-1052 (Print), 227-202X (Online) Kashmir Conflict: A Critical Analysis Saifuddin Ahmed1 Anurug Chakma2 Abstract The conflict between India and Pakistan over Kashmir which is considered as the major obstacle in promoting regional integration as well as in bringing peace in South Asia is one of the most intractable and long-standing conflicts in the world. The conflict originated in 1947 along with the emergence of India and Pakistan as two separate independent states based on the ‘Two-Nations’ theory. Scholarly literature has found out many factors that have contributed to cause and escalate the conflict and also to make protracted in nature. Five armed conflicts have taken place over the Kashmir. The implications of this protracted conflict are very far-reaching. Thousands of peoples have become uprooted; more than 60,000 people have died; thousands of women have lost their beloved husbands; nuclear arms race has geared up; insecurity has increased; in spite of huge destruction and war like situation the possibility of negotiation and compromise is still absence . This paper is an attempt to analyze the causes and consequences of Kashmir conflict as well as its security implications in South Asia. Introduction Jahangir writes: “Kashmir is a garden of eternal spring, a delightful flower-bed and a heart-expanding heritage for dervishes. Its pleasant meads and enchanting cascades are beyond all description. There are running streams and fountains beyond count. Wherever the eye -

Final-1-August-2021-3Rd-FHRJK-Report-AM.Pdf

i TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements Report and Methodology Executive Summary and Recommendations vi List of Rights that Continue to be Violated: 1 1. Civilian Security 10 2. Children, Women and Health 34 3. Land, Demography and Identity Rights 40 4. Industry and Employment 46 5. The Freedom of Media, Speech & Information 51 Conclusion 56 List of abbreviations 57 Appendix: About the Forum 58 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The Forum for Human Rights in Jammu and Kashmir would like to express deep gratitude to Shivani Sanghavi, who drafted this Report, and to Amjad Majid for the layout. iii THE REPORT AND METHODOLOGY The Forum for Human Rights in Jammu and Kashmir comprises an informal group of concerned citizens who believe that, in the prevailing situation in the former state, an independent initiative is required so that continuing human rights violations do not go unnoticed. This is the third report issued by the Forum. It has largely been compiled from government sources, media accounts (carried in well-established and reputed newspapers or television), NGO fact-finding reports, interviews, and information garnered through legal petitions. The report relies primarily on information collected between 1 February 2021 and 23 July 2021. Though in situ verification has not been possible during the Covid-19 lockdown, the various sources listed above have been fact-checked against each other to ensure the information is as accurate as possible, and only that information has been carried that appears to be well-founded. Where there is any doubt regarding a piece of information, queries have been footnoted. [email protected] iv Members of the Forum Co-Chairs: Justice Madan B. -

Russian Influence on India's Military Doctrines

COMMENTARY Russian Influence on India’s Military Doctrines VIPIN NARANG espite a growing relationship since 2000 between the United States and India and various designations that each is a “strategic partner” or “major defense partner,” India’s three conventional services and increasingly its nuclear program—as it moves to sea—are largely dependent on another country D 1 for mainline military equipment, India’s historical friend: Russia. Since the 1970s, each of the conventional services has had a strong defense procurement relationship with Russia, who tends to worry less than the United States about transferring sensitive technologies. Currently, each of the services operates frontline equipment that is Russian— the Army with T-90 tanks, the Air Force with both MiGs and Su-30MKIs, and the Navy with a suite of nuclear-powered submarines (SSBN) and aircraft carri- ers that are either Russian or whose reactors were designed with Russian assis- tance. This creates a dependence on Russia for spare parts, maintenance, and training that outstrips any dependency India has for military equipment or op- erations. In peacetime, India’s force posture readiness is critically dependent on maintenance and spare parts from Russia. In a protracted conflict, moreover, Rus- sia could cripple India’s military services by withholding replacements and spares. This means India cannot realistically unwind its relationship with Moscow for at least decades, while these platforms continue to serve as the backbone of Indian military power. In terms of doctrine and strategy, although it may be difficult to trace direct influence and lineage between Russia and India, there are several pieces in India’s conventional and nuclear strategy that at least mirror Russia’s behavior. -

10 Pakistan's Nuclear Program

10 PAKISTAN’S NUCLEAR PROGRAM Laying the groundwork for impunity C. Christine Fair Contemporary analysts of Pakistan’s nuclear program speciously assert that Pakistan began acquiring a nuclear weapons capability after the 1971 war with India in which Pakistan was vivisected. In this conventional account, India’s 1974 nuclear tests gave Pakistan further impetus for its program.1 In fact, Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan’s first popularly elected prime minister, ini- tiated the program in the late 1960s despite considerable opposition from Pakistan’s first military dictator General Ayub Khan (henceforth Ayub). Bhutto presciently began arguing for a nuclear weapons program as early as 1964 when China detonated its nuclear devices at Lop Nor and secured its position as a permanent nuclear weapons state under the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty (NPT). Considering China’s test and its defeat of India in the 1962 Sino–Indian war, Bhutto reasoned that India, too, would want to develop a nuclear weapon. He also knew that Pakistan’s civilian nuclear program was far behind India’s, which predated independence in 1947. Notwithstanding these arguments, Ayub opposed acquiring a nuclear weapon both because he believed it would be an expensive misadventure and because he worried that doing so would strain Pakistan’s western alliances, formalized through the Central Treaty Organization (CENTO) and the South-East Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO). Ayub also thought Pakistan would be able to buy a nuclear weapon “off the shelf” from one of its allies if India acquired one first.2 With the army opposition obstructing him, Bhutto was unable to make any significant nuclear headway until 1972, when Pakistan’s army lay in disgrace after losing East Pakistan in its 1971 war with India. -

1 the Turks and Europe by Gaston Gaillard London: Thomas Murby & Co

THE TURKS AND EUROPE BY GASTON GAILLARD LONDON: THOMAS MURBY & CO. 1 FLEET LANE, E.C. 1921 1 vi CONTENTS PAGES VI. THE TREATY WITH TURKEY: Mustafa Kemal’s Protest—Protests of Ahmed Riza and Galib Kemaly— Protest of the Indian Caliphate Delegation—Survey of the Treaty—The Turkish Press and the Treaty—Jafar Tayar at Adrianople—Operations of the Government Forces against the Nationalists—French Armistice in Cilicia—Mustafa Kemal’s Operations—Greek Operations in Asia Minor— The Ottoman Delegation’s Observations at the Peace Conference—The Allies’ Answer—Greek Operations in Thrace—The Ottoman Government decides to sign the Treaty—Italo-Greek Incident, and Protests of Armenia, Yugo-Slavia, and King Hussein—Signature of the Treaty – 169—271 VII. THE DISMEMBERMENT OF THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE: 1. The Turco-Armenian Question - 274—304 2. The Pan-Turanian and Pan-Arabian Movements: Origin of Pan-Turanism—The Turks and the Arabs—The Hejaz—The Emir Feisal—The Question of Syria—French Operations in Syria— Restoration of Greater Lebanon—The Arabian World and the Caliphate—The Part played by Islam - 304—356 VIII. THE MOSLEMS OF THE FORMER RUSSIAN EMPIRE AND TURKEY: The Republic of Northern Caucasus—Georgia and Azerbaïjan—The Bolshevists in the Republics of Caucasus and of the Transcaspian Isthmus—Armenians and Moslems - 357—369 IX. TURKEY AND THE SLAVS: Slavs versus Turks—Constantinople and Russia - 370—408 2 THE TURKS AND EUROPE I THE TURKS The peoples who speak the various Turkish dialects and who bear the generic name of Turcomans, or Turco-Tatars, are distributed over huge territories occupying nearly half of Asia and an important part of Eastern Europe.