Final-1-August-2021-3Rd-FHRJK-Report-AM.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Relilance Santa Cruz (E) Fax: +91 22 4303 1664 Mumbai 400 055 CIN: L75100MH1929PLC001530

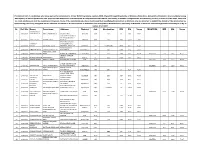

Reliance Infrastructure Limited Reliance Centre Tel: +91 22 4303 1000 ReLIlANce Santa Cruz (E) Fax: +91 22 4303 1664 Mumbai 400 055 www.rinfra.com CIN: L75100MH1929PLC001530 October 9, 2019 SSE Limited National Stock Exchange of India Phiroze Jeejeebhoy Towers, Limited Dalal Street, Exchange Plaza, 5th Floor, Mumbai 400 001 Plot No. C/1, G Block, SSE Scrip Code: 500390 Bandra Kurla Complex, Bandra (East), Mumbai 400 051 NSE Scrip Symbol: RELINFRA Dear Sirs, Sub: Disclosure under Regulation 30 of SEBI (Listing Obligation and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations 2015 In terms of Regulation 30 of the Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements) Regulations, 2015 read with Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD/4/2015 dated September 9, 2015 issued by the Securities and Exchange Board of India, we make the disclosure as regards change in Directors of the Company in the prescribed format as attached. The Board hereby confirms that the Directors being appointed are not debarred from holding the office of director by virtue of any SEBI order or any other such authority. We also enclose herewith the media release in the given matter. Yours faithfully For Reliance Infrastructure Limited Paresh Rathod Company Secretary Ene!.: As above Registered Office: Reliance Centre, Ground Floor, 19, Walchand Hirachand Marg, Ballard Estate, Mumbai 400 001. ReLIJANce Annexure Information pursuant to Regulation 30 of Securities and Exchange Board of India (Listing Obligations and Disclosure Requirements), Regulations, 2015 read with Circular No. CIR/CFD/CMD/4/2015 dated September 9,2015 issued by SEBI 1. Reason for change: a. Appointment of Shri Jai Anmol Ambani and Shri Jai Anshul Ambani, as additional Directors on the Board of the Company in the capacity of Non Executive Directors, and b. -

City Coins Post Al Medal Auction No. 68 2017

Complete visual CITY COINS CITY CITY COINS POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION NO. 68 MEDAL POSTAL POSTAL Medal AUCTION 2017 68 POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 68 CLOSING DATE 1ST SEPTEMBER 2017 17.00 hrs. (S.A.) GROUND FLOOR TULBAGH CENTRE RYK TULBAGH SQUARE FORESHORE CAPE TOWN, 8001 SOUTH AFRICA P.O. BOX 156 SEA POINT, 8060 CAPE TOWN SOUTH AFRICA TEL: +27 21 425 2639 FAX: +27 21 425 3939 [email protected] • www.citycoins.com CATALOGUE AVAILABLE ELECTRONICALLY ON OUR WEBSITE INDEX PAGES PREFACE ................................................................................................................................. 2 – 3 THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE 1880-1881 4 – 9 by ROBERT MITCHELL........................................................................................................................ ALPHABETICAL SURNAME INDEX ................................................................................ 114 PRICES REALISED – POSTAL MEDAL AUCTION 67 .................................................... 121 . BIDDING GUIDELINES REVISED ........................................................................................ 124 CONDITIONS OF SALE REVISED ........................................................................................ 125 SECTION I LOTS THE FIRST BOER WAR OF INDEPENDENCE; MEDALS ............................................. 1 – 9 SOUTHERN AFRICAN VICTORIAN CAMPAIGN MEDALS ........................................ 10 – 18 THE ANGLO BOER WAR 1899-1902: – QUEEN’S SOUTH AFRICA MEDALS ............................................................................. -

High Court of Jammu and Kashmir Srinagar Bench. 7

HIGH COURT OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR SRINAGAR BENCH. 7 ADVANCE LIST {05-07-2021 TO 09-07-2021} I N D E X Court HON’BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE BENCH 05/07/21 06/07/21 07/07/21 08/07/21 09/07/21 No. /HON’BLE JUDGES ID: Court HON’BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE 1532 1-4 34-38 69-72 102-104 131-134 No. 1 & HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE SANJAY DHAR Court HON’BLE THE CHIEF JUSTICE 1520 - - - - 135 No. 1 Court HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE 1400 5-24 39-57 73-91 105-120 136-154 No. 2 ALI MOHAMMAD MAGREY Court HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE 1405 25-29 58-64 92-96 121-127 155-159 No. 4 TASHI RABSTAN Court HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE 1407 30-33 65-68 97-101 128-130 160-163 No. 5 SANJEEV KUMAR Court HON’BLE MR. JUSTICE 1496 - - - - 164-165 No. 9 SANJAY DHAR NOTICE ON NEXT PAGE (Gowher Majid Dalal) BY ORDER REGISTRAR JUDICIAL www.jkhighcourt.nic.in [email protected] HIGH COURT OF JAMMU AND KASHMIR AT SRINAGAR ******** NOTICE No. I All the fresh matters presented before the Registry at the filling Counter, on a particular working day upto 12:00 pm ,shall be listed for hearing, before the various Benches of the Hon’ble Court on the next working day, if after scrutinization, are found complete in all respects and defect free. Caveat, if any shall be distinctively mentioned. No. II All fresh matter(s) coming by way of Daily Supplementary List shall be listed before all the available single roster benches in equal proportion. -

Russian Influence on India's Military Doctrines

COMMENTARY Russian Influence on India’s Military Doctrines VIPIN NARANG espite a growing relationship since 2000 between the United States and India and various designations that each is a “strategic partner” or “major defense partner,” India’s three conventional services and increasingly its nuclear program—as it moves to sea—are largely dependent on another country D 1 for mainline military equipment, India’s historical friend: Russia. Since the 1970s, each of the conventional services has had a strong defense procurement relationship with Russia, who tends to worry less than the United States about transferring sensitive technologies. Currently, each of the services operates frontline equipment that is Russian— the Army with T-90 tanks, the Air Force with both MiGs and Su-30MKIs, and the Navy with a suite of nuclear-powered submarines (SSBN) and aircraft carri- ers that are either Russian or whose reactors were designed with Russian assis- tance. This creates a dependence on Russia for spare parts, maintenance, and training that outstrips any dependency India has for military equipment or op- erations. In peacetime, India’s force posture readiness is critically dependent on maintenance and spare parts from Russia. In a protracted conflict, moreover, Rus- sia could cripple India’s military services by withholding replacements and spares. This means India cannot realistically unwind its relationship with Moscow for at least decades, while these platforms continue to serve as the backbone of Indian military power. In terms of doctrine and strategy, although it may be difficult to trace direct influence and lineage between Russia and India, there are several pieces in India’s conventional and nuclear strategy that at least mirror Russia’s behavior. -

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World

Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Introduction • 1 Rana Chhina Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World i Capt Suresh Sharma Last Post Indian War Memorials Around the World Rana T.S. Chhina Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India 2014 First published 2014 © United Service Institution of India All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the author / publisher. ISBN 978-81-902097-9-3 Centre for Armed Forces Historical Research United Service Institution of India Rao Tula Ram Marg, Post Bag No. 8, Vasant Vihar PO New Delhi 110057, India. email: [email protected] www.usiofindia.org Printed by Aegean Offset Printers, Gr. Noida, India. Capt Suresh Sharma Contents Foreword ix Introduction 1 Section I The Two World Wars 15 Memorials around the World 47 Section II The Wars since Independence 129 Memorials in India 161 Acknowledgements 206 Appendix A Indian War Dead WW-I & II: Details by CWGC Memorial 208 Appendix B CWGC Commitment Summary by Country 230 The Gift of India Is there ought you need that my hands hold? Rich gifts of raiment or grain or gold? Lo! I have flung to the East and the West Priceless treasures torn from my breast, and yielded the sons of my stricken womb to the drum-beats of duty, the sabers of doom. Gathered like pearls in their alien graves Silent they sleep by the Persian waves, scattered like shells on Egyptian sands, they lie with pale brows and brave, broken hands, strewn like blossoms mowed down by chance on the blood-brown meadows of Flanders and France. -

Notification No. 51 – PSC (DR-S) of 2018 Dated: 30.01.2018

Page 1 of 69 Subject: Select List for the posts of Medical Officer (Allopathic) in Health & Medical Education Department. Notification No. 51 – PSC (DR-S) of 2018 Dated: 30.01.2018 Whereas, the Health & Medical Education Department referred 371 posts (OM:213, RBA:74, SC:29, ST:37, ALC:11 & SLC:07) of Medical Officer to the Public Service Commission for being filled up from amongst the suitable candidates; and Whereas, the Commission notified these posts vide Notification No. 01-PSC (DR-P) of 2017 dated 27.03.2017; and Whereas, in response to the above notification, 2883 applications were received; and Whereas, the written test of the candidates for selection was conducted on 26.06.2016 in which 2452 candidates appeared. The result of the written test was declared vide Notification No. PSC/Exam/2017/79 dated: 14.12.2017 in pursuance of Rule 32(a) of the J&K Public Service Commission (Conduct of Examinations) Rules, 2005 and Rule 40 of the J&K Public Service Commission (Business & Procedure) Rules, 1980 as amended from time to time and 1158 candidates were declared to have qualified the written test and called for interview; and Whereas, 01 more candidate was allowed to participate in the interview on the directions of the Hon’ble High Court in SWP No. 2834/2017, MP No.01/2017 titled Nidhi Priya Vs State of J&K & Ors. vide its order dated:30.12.2017.Her result has not been declared as per Court Orders. Whereas, the interviews of the shortlisted candidates were conducted w.e.f. -

Provisional List of Candidates Who Have Applied for Admission to 2

Provisional List of candidates who have applied for admission to 2-Year B.Ed.Programme session-2020 offered through Directorate of Distance Education, University of Kashmir. Any candidate having discrepancy in his/her particulars can approach the Directorate of Admissions & Competitive Examinations, University of Kashmir alongwith the documentary proof by or before 31-07-2021, after that no claim whatsoever shall be considered. However, those of the candidates who have mentioned their Qualifying Examination as Masters only are directed to submit the details of the Graduation by approaching personally alongwith all the relevant documnts to the Directorate of Admission and Competitive Examinaitons, University of Kashmir or email to [email protected] by or before 31-07-2021 Sr. Roll No. Name Parentage Address District Cat. Graduation MM MO %age MASTERS MM MO %age SHARIQ RAUOF 1 20610004 AHMAD MALIK ABDUL AHAD MALIK QASBA KHULL KULGAM RBA BSC 10 6.08 60.80 VPO HOTTAR TEHSILE BILLAWAR DISTRICT 2 20610005 SAHIL SINGH BISHAN SINGH KATHUA KATHUA RBA BSC 3600 2119 58.86 BAGHDAD COLONY, TANZEELA DAWOOD BRIDGE, 3 20610006 RASSOL GH RASSOL LONE KHANYAR, SRINAGAR SRINAGAR OM BCOMHONS 2400 1567 65.29 KHAWAJA BAGH 4 20610008 ISHRAT FAROOQ FAROOQ AHMAD DAR BARAMULLA BARAMULLA OM BSC 1800 912 50.67 MOHAMMAD SHAFI 5 20610009 ARJUMAND JOHN WANI PANDACH GANDERBAL GANDERBAL OM BSC 1800 899 49.94 MASTERS 700 581 83.00 SHAKAR CHINTAN 6 20610010 KHADIM HUSSAIN MOHD MUSSA KARGIL KARGIL ST BSC 1650 939 56.91 7 20610011 TSERING DISKIT TSERING MORUP -

India's Limited War Doctrine: the Structural Factor

IDSA Monograph Series No. 10 December 2012 INDIA'S LIMITED WAR DOCTRINE THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR ALI AHMED INDIA’S LIMITED WAR DOCTRINE: THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR | 1 IDSA Monograph Series No. 10 December 2012 INDIA’S LIMITED WAR DOCTRINE THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR ALI AHMED 2 | ALI AHMED Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, New Delhi. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, sorted in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo-copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses (IDSA). ISBN: 978-93-82169-09-3 Disclaimer: The views expressed in this Monograph are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Institute or the Government of India. First Published: December 2012 Price: Rs. Published by: Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses No.1, Development Enclave, Rao Tula Ram Marg, Delhi Cantt., New Delhi - 110 010 Tel. (91-11) 2671-7983 Fax.(91-11) 2615 4191 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.idsa.in Layout & Cover by: Vaijayanti Patankar Printed at: INDIA’S LIMITED WAR DOCTRINE: THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR | 3 To Late Maj Gen S. C. Sinha, PVSM 4 | ALI AHMED INDIA’S LIMITED WAR DOCTRINE: THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR | 5 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .......................... 7 1. INTRODUCTION .................................... 9 2. DOCTRINAL CHANGE ............................. 16 3. THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR .................. 42 4. CONCLUSION ....................................... 68 REFERENCES ......................................... 79 6 | ALI AHMED * INDIA’S LIMITED WAR DOCTRINE: THE STRUCTURAL FACTOR | 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This monograph is the outcome of my fellowship at IDSA in 2010- 12. -

Cold Start – Hot Stop? a Strategic Concern for Pakistan

79 COLD START – HOT STOP? A STRATEGIC CONCERN FOR PAKISTAN * Muhammad Ali Baig Abstract The hostile environment in South Asia is a serious concern for the international players. This volatile situation is further fuelled by escalating arms race and aggressive force postures. The Indian Cold Start Doctrine (CSD) has supplemented negatively to the South Asian strategic stability by trying to find a way in fighting a conventional limited war just below the nuclear umbrella. It was reactionary in nature to overcome the shortcomings exhibited during Operation Parakram of 2001-02, executed under the premise of Sundarji Doctrine. The Cold Start is an adapted version of German Blitzkrieg which makes it a dangerous instrument. Apart from many limitations, the doctrine remains relevant to the region, primarily due to the attestation of its presence by the then Indian Army Chief General Bipin Rawat in January 2017. This paper is an effort to probe the different aspects of Cold Start, its prerequisites in provisions of three sets; being a bluff based on deception, myth rooted in misperception, and a reality flanked by escalation; and how and why CSD is a strategic concern for Pakistan. Keywords: Cold Start Doctrine, Strategic Stability, Conventional Warfare, Pakistan, India. Introduction here is a general consensus on the single permanent aspect of international system T that has dominated the international relations ever since and its history and relevance are as old as the existence of man and the civilization itself; the entity is called war.1 This relevance was perhaps best described by Leon Trotsky who averred that “you may not be interested in war, but war may be interested in you.”2 To fight, avert and to pose credible deterrence, armed forces strive for better yet flexible doctrines to support their respective strategies in conducting defensive as well as offensive operations and to dominate in adversarial environments. -

Annual Report 2015-16 Padma Vibhushan Shri Dhirubhai H

Defence and Engineering Annual Report 2015-16 Padma Vibhushan Shri Dhirubhai H. Ambani (28th December, 1932 - 6th July, 2002) Reliance Group - Founder and Visionary Profile Reliance Defence and Engineering Limited (RDEL) (formerly Pipavav Defence and Offshore Engineering Company Limited) has the largest engineering infrastructure in India and is one of the largest in the world. RDEL is the first private sector company in India to obtain the licence and contract to build warships. RDEL operates India’s largest integrated shipbuilding facility with 662M x 65M Dry dock. The facility houses the only modular shipbuilding facility with a capacity to build fully fabricated and outfitted blocks. The fabrication facility is spread over 2.1 million sq.ft. The Shipyard has a pre-erection berth of 980 meters length and 40 meters width, and two Goliath Cranes with combined lifting capacity of 1200 tonnes, besides outfitting berths length of 780 meters. Mission • Meet and exceed customer expectations with a collaborative approach • Consistently enhance competitiveness and deliver profitable growth • Adopt global best practices and create a culture of quality to be the Industry leader • Achieve excellence in project execution in maritime domain ensuring quality, reliability, safety and operational efficiency • Relentlessly pursuing new opportunities and technologies • Encourage ideas, talent and value systems • Promote a work culture that fosters learning, individual growth and team building • Practice high standards of corporate governance and be a financially sound organization • Earn the trust and confidence of stakeholders, exceeding their expectations • Be a partner in nation building and contribute towards the country’s economic growth . This Report is printed on environment friendly paper. -

CIN Company Name First Name Middle Name Last Name Father

CIN L15142GJ1992PLC018745 Company Name Sum of unpaid and unclaimed dividend 12316.82 Sum of matured deposit 0 Sum of matured debentures 0 Sum of application money due for refund 0 First Name Middle Name Last Name Father/Husb Father/Husb Father/Husband and First and Middle Last Name Name Name ABDUL KHALIQ ISARUDDIN JUGAL ABHISHEK KISHORE SHARMA SHARMA AJAY KUMAR B NA MR VIJAY AMIT KUMAR KUMAR VERMA VERMA AMIT RAMBHAI DANGAR NA ISHWAR DAYAL AMIT VERMA VERMA AMITKUMAR KAILASHCHA KAILASHCHA NDRA NDRA SURAJLAL AGRAWAL AGRAWAL ANANDRAO KAMALAKAR KAMALAKAR SHANKAR JADHAV JADHAV ANBAZHAGA N NA KARINGAMA ANIL DATHIL THOTTAPPILL GOVINDANK Y UTTY ANILKUMAR SANKARANN K S AIR SUBHASH ANITA CHAND AGGARWAL AGGARWAL ANITA GHANSHYA SHARMA M SHARMA ARCHNA NARESH PATODI PATODI PRAVEEN ARUN KUMAR SHARMA SHARMA ARUNA ASHOKKUM ASHOKKUMA AR R BAGRODIA BAGRODIA ARVIND KUMAR PAWAN PAWAN KUMAR AGARWAL AGGARWAL ASHA CHERIAN NA SHYAM ASHA RANI SUNDER GUPTA GUPTA ASHIF YUSUFBHAI YUSUF BHAI CHHIPA CHHIPA ASHOK BHAI GOPALBHAI G VASAVA K VASAVA ASHOK KUMAR BISHANDAS BISHANDAS GURUPIARA GUPTA GUPTA ASHOK KRUSHNA KUMAR CHANDRA PRUSTY PRUSTY ASHOK MURLI DHAR MAHESHWAR MAHESHWA I RI PRAVINCHA ASID NDRA PRAVINCHAN GOVINDLAL DRA PADHYA PADHYA AWARI DEORAM GANESH RANGNATH DEORAM AWARI BABAN KISAN KISAN GANU INDALKAR INDALKAR BABIBEN NAVINBHAI NAVINBHAI KESHAVLAL PATEL PATEL BABUBHAI SAVJIBHAI SAVJIBHAI ROKAD ROKAD BALAPRASAD SADASHIVRA SADASHIVRA O DHONDGE O DHONDGE BANSILAL B BHARULAL PALIWAL PALIWAL BASHIR ABDULKADIR ABDUL KADIR ABDULLA HATHILA HATHILA BHALCHAND RA KALANBHAI -

Role of Persians at the Mughal Court: a Historical

ROLE OF PERSIANS AT THE MUGHAL COURT: A HISTORICAL STUDY, DURING 1526 A.D. TO 1707 A.D. PH.D THESIS SUBMITTED BY, MUHAMMAD ZIAUDDIN SUPERVISOR: PROF. DR. MUNIR AHMED BALOCH IN THE AREA STUDY CENTRE FOR MIDDLE EAST & ARAB COUNTRIES UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN QUETTA, PAKISTAN. FOR THE FULFILMENT OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY 2005 DECLARATION BY THE CANDIDATE I, Muhammad Ziauddin, do solemnly declare that the Research Work Titled “Role of Persians at the Mughal Court: A Historical Study During 1526 A.D to 1707 A.D” is hereby submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy and it has not been submitted elsewhere for any Degree. The said research work was carried out by the undersigned under the guidance of Prof. Dr. Munir Ahmed Baloch, Director, Area Study Centre for Middle East & Arab Countries, University of Balochistan, Quetta, Pakistan. Muhammad Ziauddin CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. Muhammad Ziauddin has worked under my supervision for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. His research work is original. He fulfills all the requirements to submit the accompanying thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Prof. Dr. Munir Ahmed Research Supervisor & Director Area Study Centre For Middle East & Arab Countries University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan. Prof. Dr. Mansur Akbar Kundi Dean Faculty of State Sciences University of Balochistan Quetta, Pakistan. d DEDICATED TO THE UNFORGETABLE MEMORIES OF LATE PROF. MUHAMMAD ASLAM BALOCH OF HISTORY DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF BALOCHISTAN, QUETTA PAKISTAN e ACKNOWLEDGMENT First of all I must thank to Almighty Allah, who is so merciful and beneficent to all of us, and without His will we can not do anything; it is He who guide us to the right path, and give us sufficient knowledge and strength to perform our assigned duties.