A Cold Start for Hot Wars? a Cold Start for Walter C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Share to Be Transferred to IEPF.Xlsx

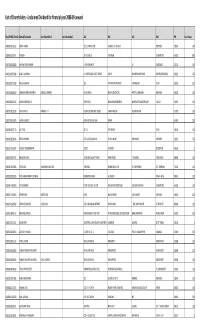

List of Shareholders ‐ Unclaimed Dividend for financial year 2008‐09 onward Folio/DP‐ID & Client ID Name of Shareholder Joint Shareholder 1 Joint Shareholder 2 AD1 AD2 AD3 AD4 PIN No of shares IN30009510512622 SHANTI TOMAR 125, HUMAYUN PUR SAFDARJUNG ENCLAVE NEW DELHI 110029 100 IN30009511023704 P SURESH 28 R R LAYOUT R S PURAM COIMBATORE 641001 1000 IN30011810558083 SHIV RAJ SINGH SHARMA V P.O. MAKANPUR UP GHAZIABAD 201010 100 IN30011810706380 NAND LAL MENANI C O KASTURI BAI COLD STORAGE HAPUR BULANDSHAHAR ROAD HAPUR (GHAZIABAD) 245101 100 IN30011810772083 RAHUL AGRAWAL 362 SITA RAM APARTMENTS PATPARGANJ DELHI 110092 200 IN30011810804832 SARBINDER SINGH SAWHNEY HARLEEN SAWHNEY HOUSE NO 65 WEST AVENUE ROAD WEST PUNJABI BAGH NEW DELHI 110026 200 IN30011810878226 ASHOK KUMAR MALIK S/W 393/14 NEAR MAHABIR MANDIR MAIN BAZAR BAHADUR GARH JHAJJAR 124507 100 IN30017510122592 VIJI KANNAN. K KANNAN. K. R 4/146 A SECOND MAIN STREET SHANTHI NAGAR PALAYANKOTTAI 627002 100 IN30017510155076 SATISH KUMAR. D INDIAN OVERSEAS BANK ANNUR 641653 200 IN30020610257473 M L GOYAL QP ‐ 31 PITAMPURA DELHI 110034 100 IN30020610296246 DEEPAK SHARMA FLAT‐3, SOOD BUILDING TEL MILL MARG RAM NAGAR NEW DELHI 110055 700 IN30021413290147 GUDURU SUBRAMANYAM 10/471 K K STREET PRODDATUR 516360 1 IN30023910397325 BALAMURUGAN V 1073/133H, MILLAR PURAM ANNA NAGAR TUTUCORIN TAMIL NADU 628008 200 IN30026310156836 SUTAPA SEN SAMARESH KUMAR SEN TURI PARA DIGHIRPAR,N.C.PUR PO‐ RAMPURHAT DIST‐ BIRBHUM 731224 100 IN30034320058199 PATEL HARGOVANBHAI VELABHAI LIMDAWALO MADH JAL CHOWK -

India-Pakistan Conflict: Records of the Us State Department, February 1963

http://gdc.gale.com/archivesunbound/ INDIA-PAKISTAN CONFLICT: RECORDS OF THE U.S. STATE DEPARTMENT, FEBRUARY 1963-1966 Over 16,000 pages of State Department Central Files on India and Pakistan from 1963 through 1966 make this collection a standard documentary resource for the study of the political relations between India and Pakistan during a crucial period in the Cold War and the shifting alliances and alignments in South Asia. Date Range: 1963-1966 Content: 15,387 images Source Library: U.S. National Archives Detailed Description: Relations with Pakistan have demanded a high proportion of India’s international energies and undoubtedly will continue to do so. India and Pakistan have divergent national ideologies and have been unable to establish a mutually acceptable power equation in South Asia. The national ideologies of pluralism, democracy, and secularism for India and of Islam for Pakistan grew out of the pre-independence struggle between the Congress and the All-India Muslim League, and in the early 1990s the line between domestic and foreign politics in India’s relations with Pakistan remained blurred. Because great-power competition—between the United States and the Soviet Union and between the Soviet Union and China—became intertwined with the conflicts between India and Pakistan, India was unable to attain its goal of insulating South Asia from global rivalries. This superpower involvement enabled Pakistan to use external force in the face of India’s superior endowments of population and resources. The most difficult problem in relations between India and Pakistan since partition in August 1947 has been their dispute over Kashmir. -

A Look Into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan Over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori

A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir Written by Pranav Asoori This PDF is auto-generated for reference only. As such, it may contain some conversion errors and/or missing information. For all formal use please refer to the official version on the website, as linked below. A Look into the Conflict Between India and Pakistan over Kashmir https://www.e-ir.info/2020/10/07/a-look-into-the-conflict-between-india-and-pakistan-over-kashmir/ PRANAV ASOORI, OCT 7 2020 The region of Kashmir is one of the most volatile areas in the world. The nations of India and Pakistan have fiercely contested each other over Kashmir, fighting three major wars and two minor wars. It has gained immense international attention given the fact that both India and Pakistan are nuclear powers and this conflict represents a threat to global security. Historical Context To understand this conflict, it is essential to look back into the history of the area. In August of 1947, India and Pakistan were on the cusp of independence from the British. The British, led by the then Governor-General Louis Mountbatten, divided the British India empire into the states of India and Pakistan. The British India Empire was made up of multiple princely states (states that were allegiant to the British but headed by a monarch) along with states directly headed by the British. At the time of the partition, princely states had the right to choose whether they were to cede to India or Pakistan. To quote Mountbatten, “Typically, geographical circumstance and collective interests, et cetera will be the components to be considered[1]. -

EDUCATION in CHINA a Snapshot This Work Is Published Under the Responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD

EDUCATION IN CHINA A Snapshot This work is published under the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of OECD member countries. This document and any map included herein are without prejudice to the status of or sovereignty over any territory, to the delimitation of international frontiers and boundaries and to the name of any territory, city or area. Photo credits: Cover: © EQRoy / Shutterstock.com; © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © astudio / Shutterstock.com Inside: © iStock.com/iPandastudio; © li jianbing / Shutterstock.com; © tangxn / Shutterstock.com; © chuyuss / Shutterstock.com; © astudio / Shutterstock.com; © Frame China / Shutterstock.com © OECD 2016 You can copy, download or print OECD content for your own use, and you can include excerpts from OECD publications, databases and multimedia products in your own documents, presentations, blogs, websites and teaching materials, provided that suitable acknowledgement of OECD as source and copyright owner is given. All requests for public or commercial use and translation rights should be submitted to [email protected]. Requests for permission to photocopy portions of this material for public or commercial use shall be addressed directly to the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) at [email protected] or the Centre français d’exploitation du droit de copie (CFC) at [email protected]. Education in China A SNAPSHOT Foreword In 2015, three economies in China participated in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment, or PISA, for the first time: Beijing, a municipality, Jiangsu, a province on the eastern coast of the country, and Guangdong, a southern coastal province. -

Group Identity and Civil-Military Relations in India and Pakistan By

Group identity and civil-military relations in India and Pakistan by Brent Scott Williams B.S., United States Military Academy, 2003 M.A., Kansas State University, 2010 M.M.A., Command and General Staff College, 2015 AN ABSTRACT OF A DISSERTATION submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Security Studies College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2019 Abstract This dissertation asks why a military gives up power or never takes power when conditions favor a coup d’état in the cases of Pakistan and India. In most cases, civil-military relations literature focuses on civilian control in a democracy or the breakdown of that control. The focus of this research is the opposite: either the returning of civilian control or maintaining civilian control. Moreover, the approach taken in this dissertation is different because it assumes group identity, and the military’s inherent connection to society, determines the civil-military relationship. This dissertation provides a qualitative examination of two states, Pakistan and India, which have significant similarities, and attempts to discern if a group theory of civil-military relations helps to explain the actions of the militaries in both states. Both Pakistan and India inherited their military from the former British Raj. The British divided the British-Indian military into two militaries when Pakistan and India gained Independence. These events provide a solid foundation for a comparative study because both Pakistan’s and India’s militaries came from the same source. Second, the domestic events faced by both states are similar and range from famines to significant defeats in wars, ongoing insurgencies, and various other events. -

Pakistan's Nuclear Weapons

Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Paul K. Kerr Analyst in Nonproliferation Mary Beth Nikitin Specialist in Nonproliferation August 1, 2016 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL34248 Pakistan’s Nuclear Weapons Summary Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal probably consists of approximately 110-130 nuclear warheads, although it could have more. Islamabad is producing fissile material, adding to related production facilities, and deploying additional nuclear weapons and new types of delivery vehicles. Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal is widely regarded as designed to dissuade India from taking military action against Pakistan, but Islamabad’s expansion of its nuclear arsenal, development of new types of nuclear weapons, and adoption of a doctrine called “full spectrum deterrence” have led some observers to express concern about an increased risk of nuclear conflict between Pakistan and India, which also continues to expand its nuclear arsenal. Pakistan has in recent years taken a number of steps to increase international confidence in the security of its nuclear arsenal. Moreover, Pakistani and U.S. officials argue that, since the 2004 revelations about a procurement network run by former Pakistani nuclear official A.Q. Khan, Islamabad has taken a number of steps to improve its nuclear security and to prevent further proliferation of nuclear-related technologies and materials. A number of important initiatives, such as strengthened export control laws, improved personnel security, and international nuclear security cooperation programs, have improved Pakistan’s nuclear security. However, instability in Pakistan has called the extent and durability of these reforms into question. Some observers fear radical takeover of the Pakistani government or diversion of material or technology by personnel within Pakistan’s nuclear complex. -

Armed Forces Tribunal, Regional Bench, Kochi O.A

ARMED FORCES TRIBUNAL, REGIONAL BENCH, KOCHI O.A.Nos. 70 of 2011 & 118 of 2013 FRIDAY, THE 21ST DAY OF NOVEMBER, 2014/30TH KARTHIKA, 1936 CORAM: HON'BLE MR. JUSTICE SHRIKANT TRIPATHI, MEMBER (J) HON'BLE VICE ADMIRAL M.P.MURALIDHARAN,AVSM & BAR, NM, MEMBER (A) O.A.NO.70 OF 2011: APPLICANT: JC-459291W EX-NB SUB CLK SAJEEV MOHAN K, AGED 45 YEARS, RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA-590 009. BY ADV.SRI.RAMESH.C.R. VERSUS RESPONDENTS: 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. 2. THE CHIEF OF ARMY STAFF, INTEGRATED HQRS. OF MOD (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. 3. THE ADJUTANT GENERAL, AG'S BRANCH, ARMY HEADQUARTERS, DHQ.P.O., NEW DELHI-110011. 4. THE GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING (WESTERN COMMAND), CNANDIMANDIR (UT), ARMY PIN CODE – 908543. O.A.70 of 2011 & 118 of 2013 - 2 - 5. THE GENERAL OFFICER COMMANDING (HQR), 7 INF DIV, PIN – 908407, C/O.56 APO. 6. THE DIRECTOR, RECRUITING, ARMY RECRUITING OFFICE, FEROZPUR, PUNJAB, C/O.56 APO. 7. THE OFFICER-IN-CHARGE, WESTERN COMMAND, IS GROUP, CHANDIMANDIR (UT) ARMY PIN 904992. 8. THE RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA-590 009. BY ADV.SRI.K.M.JAMALUDHEEN, SENIOR PANEL COUNSEL O.A.NO.118 OF 2013: APPLICANT: JC-459291W NB SUB CLK SAJEEV MOHAN K, AGED 43 YEARS, RECORDS, THE MARATHA LIGHT INFANTRY, BELGAUM, KARNATAKA-590 009. BY ADV.SRI.RAMESH.C.R. VERSUS RESPONDENTS: 1. THE UNION OF INDIA, THROUGH THE SECRETARY, MINISTRY OF DEFENCE (ARMY), SOUTH BLOCK, NEW DELHI – 110 001. -

The Terrorism Trap: the Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 8-2019 The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror John Akins University of Tennessee, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Recommended Citation Akins, John, "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2019. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/5624 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by John Akins entitled "The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America's War on Terror." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Political Science. Krista Wiegand, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Brandon Prins, Gary Uzonyi, Candace White Accepted for the Council: Dixie L. Thompson Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) The Terrorism Trap: The Hidden Impact of America’s War on Terror A Dissertation Presented for the Doctor of Philosophy Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville John Harrison Akins August 2019 Copyright © 2019 by John Harrison Akins All rights reserved. -

QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of Access Technologies for Broadband Communications

International Telecommunication Union QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of access technologies for broadband communications ITU-D STUDY GROUP 2 3rd STUDY PERIOD (2002-2006) Report on broadband access technologies eport on broadband access technologies QUESTION 20-1/2 R International Telecommunication Union ITU-D THE STUDY GROUPS OF ITU-D The ITU-D Study Groups were set up in accordance with Resolutions 2 of the World Tele- communication Development Conference (WTDC) held in Buenos Aires, Argentina, in 1994. For the period 2002-2006, Study Group 1 is entrusted with the study of seven Questions in the field of telecommunication development strategies and policies. Study Group 2 is entrusted with the study of eleven Questions in the field of development and management of telecommunication services and networks. For this period, in order to respond as quickly as possible to the concerns of developing countries, instead of being approved during the WTDC, the output of each Question is published as and when it is ready. For further information: Please contact Ms Alessandra PILERI Telecommunication Development Bureau (BDT) ITU Place des Nations CH-1211 GENEVA 20 Switzerland Telephone: +41 22 730 6698 Fax: +41 22 730 5484 E-mail: [email protected] Free download: www.itu.int/ITU-D/study_groups/index.html Electronic Bookshop of ITU: www.itu.int/publications © ITU 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, by any means whatsoever, without the prior written permission of ITU. International Telecommunication Union QUESTION 20-1/2 Examination of access technologies for broadband communications ITU-D STUDY GROUP 2 3rd STUDY PERIOD (2002-2006) Report on broadband access technologies DISCLAIMER This report has been prepared by many volunteers from different Administrations and companies. -

Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S

Doing Business in Malaysia: 2014 Country Commercial Guide for U.S. Companies INTERNATIONAL COPYRIGHT, U.S. & FOREIGN COMMERCIAL SERVICE AND U.S. DEPARTMENT OF STATE, 2010-2014. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED OUTSIDE OF THE UNITED STATES. Chapter 1: Doing Business In Malaysia Chapter 2: Political and Economic Environment Chapter 3: Selling U.S. Products and Services Chapter 4: Leading Sectors for U.S. Export and Investment Chapter 5: Trade Regulations, Customs and Standards Chapter 6: Investment Climate Chapter 7: Trade and Project Financing Chapter 8: Business Travel Chapter 9: Contacts, Market Research and Trade Events Chapter 10: Guide to Our Services Return to table of contents Chapter 1: Doing Business In Malaysia Market Overview Market Challenges Market Opportunities Market Entry Strategy Market Overview Return to top For centuries, Malaysia has profited from its location at a crossroads of trade between the East and West, a tradition that carries into the 21st century. Geographically blessed, peninsular Malaysia stretches the length of the Strait of Malacca, one of the most economically and politically important shipping lanes in the world. Capitalizing on its location, Malaysia has been able to transform its economy from an agriculture and mining base in the early 1970s to a relatively high-tech, competitive nation, where services and manufacturing now account for 75% of GDP (51% in services and 24% in manufacturing in 2013). In 2013, U.S.-Malaysia bilateral trade was an estimated US$44.2 billion counting both manufacturing and services,1 ranking Malaysia as the United States’ 20th largest trade partner. Malaysia is America’s second largest trading partner in Southeast Asia, after Singapore. -

Russian Influence on India's Military Doctrines

COMMENTARY Russian Influence on India’s Military Doctrines VIPIN NARANG espite a growing relationship since 2000 between the United States and India and various designations that each is a “strategic partner” or “major defense partner,” India’s three conventional services and increasingly its nuclear program—as it moves to sea—are largely dependent on another country D 1 for mainline military equipment, India’s historical friend: Russia. Since the 1970s, each of the conventional services has had a strong defense procurement relationship with Russia, who tends to worry less than the United States about transferring sensitive technologies. Currently, each of the services operates frontline equipment that is Russian— the Army with T-90 tanks, the Air Force with both MiGs and Su-30MKIs, and the Navy with a suite of nuclear-powered submarines (SSBN) and aircraft carri- ers that are either Russian or whose reactors were designed with Russian assis- tance. This creates a dependence on Russia for spare parts, maintenance, and training that outstrips any dependency India has for military equipment or op- erations. In peacetime, India’s force posture readiness is critically dependent on maintenance and spare parts from Russia. In a protracted conflict, moreover, Rus- sia could cripple India’s military services by withholding replacements and spares. This means India cannot realistically unwind its relationship with Moscow for at least decades, while these platforms continue to serve as the backbone of Indian military power. In terms of doctrine and strategy, although it may be difficult to trace direct influence and lineage between Russia and India, there are several pieces in India’s conventional and nuclear strategy that at least mirror Russia’s behavior. -

Biographies Introduction V4 0

2020 www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Author: Robert PALMER, M.A. BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES An introduction to the Biographies of officers in the British Army and pre-partition Indian Army published on the web-site www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk, including: • Explanation of Terms, • Regular Army, Militia and Territorial Army, • Type and Status of Officers, • Rank Structure, • The Establishment, • Staff and Command Courses, • Appointments, • Awards and Honours. Copyright ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk (2020) 13 May 2020 [BRITISH MILITARY HISTORY BIOGRAPHIES] British Military History Biographies This web-site contains selected biographies of some senior officers of the British Army and Indian Army who achieved some distinction, notable achievement, or senior appointment during the Second World War. These biographies have been compiled from a variety of sources, which have then been subject to scrutiny and cross-checking. The main sources are:1 ➢ Who was Who, ➢ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, ➢ British Library File L/MIL/14 Indian Army Officer’s Records, ➢ Various Army Lists from January 1930 to April 1946: http://www.archive.org/search.php?query=army%20list ➢ Half Year Army List published January 1942: http://www.archive.org/details/armylisthalfjan1942grea ➢ War Services of British Army Officers 1939-46 (Half Yearly Army List 1946), ➢ The London Gazette: http://www.london-gazette.co.uk/, ➢ Generals.dk http://www.generals.dk/, ➢ WWII Unit Histories http://www.unithistories.com/, ➢ Companions of The Distinguished Service Order 1923 – 2010 Army Awards by Doug V. P. HEARNS, C.D. ➢ Various published biographies, divisional histories, regimental and unit histories owned by the author. It has to be borne in mind that discrepancies between sources are inevitable.