Designing Social Protection Frameworks for Three Zones of Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grouped by Cluster

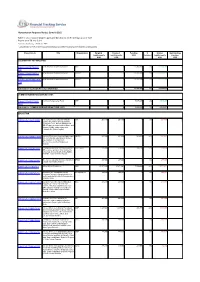

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2015 Table E: List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 28-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R##) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED SOM-15/SNYS/78452/ to be allocated to specific projects WFP 0 0 15,200,048 0% -15,200,048 0 561 SOM-15/SNYS/78471/ to be allocated to specific projects UNHCR 0 0 22,776,204 0% -22,776,204 0 120 SOM-15/SNYS/78658/R/ to be allocated to specific projects UNICEF 0 0 13,712,399 0% -13,712,399 0 124 Sub total for CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED 0 0 51,688,651 0% -51,688,651 0 COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) SOM-15/SNYS/77965/ Common Humanitarian Fund CHF 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 7622 Sub total for COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 EDUCATION SOM-15/E/71574/8380 Increasing Access & Quality of Basic JCC 201,150 201,150 0 0% 201,150 0 Literacy for Children and Adults from Vulnerable, Poor, Women Headed and IDP / Returness Households in Bu'ale and Salagle (Middle Jubba region) and Celbarde-Ato (Bakool region) SOM-15/E/71608/14579 Improved Protective Learning Spaces and FENPS 451,400 451,400 289,999 64% 161,401 0 Access to Quality Education for School Age Children in Humanitarian Emergencies and Conflict Areas in Somalia SOM-15/E/71628/5660 Emergency education for crises-affected -

Assessment Report 2011

ASSESSMENT REPORT 2011 PHASE 1 - PEACE AND RECONCILIATION JOIN- TOGETHER ACTION For Galmudug, Himan and Heb, Galgaduud and Hiiraan Regions, Somalia Yme/NorSom/GSA By OMAR SALAD BSc (HONS.) DIPSOCPOL, DIPGOV&POL Consultant, in collaboration with HØLJE HAUGSJÅ (program Manager Yme) and MOHAMED ELMI SABRIE JAMALLE (Director NorSom). 1 Table of Contents Pages Summary of Findings, Analysis and Assessment 5-11 1. Introduction 5 2. Common Geography and History Background of the Central Regions 5 3. Political, Administrative Governing Structures and Roles of Central Regions 6 4. Urban Society and Clan Dynamics 6 5. Impact of Piracy on the Economic, Social and Security Issues 6 6. Identification of Possibility of Peace Seeking Stakeholders in Central Regions 7 7. Identification of Stakeholders and Best Practices of Peace-building 9 8. How Conflicts resolved and peace Built between People Living Together According 9 to Stakeholders 9. What Causes Conflicts Both locally and regional/Central? 9 10. Best Practices of Ensuring Women participation in the process 9 11. Best Practices of organising a Peace Conference 10 12. Relations Between Central Regions and Between them TFG 10 13. Table 1: Organisation, Ownership and Legal Structure of the 10 14. Peace Conference 10 15. Conclusion 11 16. Recap 11 16.1 Main Background Points 16.2 Recommendations 16.3 Expected Outcomes of a Peace Conference Main and Detailed Report Page 1. Common geography and History Background of Central Regions 13 1.1 Overview geographical and Environmental Situation 13 1.2 Common History and interdependence 14 1.3 Chronic Neglect of Central Regions 15 1.4 Correlation Between neglect and conflict 15 2. -

Enhanced Enrolment of Pastoralists in the Implementation and Evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia

Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of the UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia Prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute UNICEF ESARO JUNE 2013 Enhanced enrolment of pastoralists in the implementation and evaluation of UNICEF-FAO-WFP Resilience Strategy in Somalia © United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), Nairobi, 2013 UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) PO Box 44145-00100 GPO Nairobi June 2013 The report was prepared for UNICEF Eastern and Southern Africa Regional Office (ESARO) by Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. The contents of this report do not necessarily reflect the policies or the views of UNICEF. The text has not been edited to official publication standards and UNICEF accepts no responsibility for errors. The designations in this publication do not imply an opinion on legal status of any country or territory, or of its authorities, or the delimitation of frontiers. For further information, please contact: Esther Schelling, Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute, University of Basel: [email protected] Eugenie Reidy, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Dorothee Klaus, UNICEF ESARO: [email protected] Cover photograph © UNICEF/NYHQ2009-2301/Kate Holt 2 Table of Contents Foreword ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

Wash Cluster Meeting Minutes

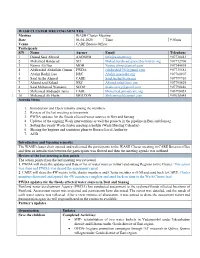

WASH CLUSTER MEETING MINUTES Meeting WASH Cluster Meeting Date 06-01-2020 Time 9;00am Venue CARE Bosaso Office Participants S/N Name Agency Email Telephone 1 Dauud Said Ahmed AADSOM [email protected] 907738443 2 Mohamed Bardacad SCI [email protected] 907772900 3 Naimo Ali Nur MOH [email protected] 907744895 4 Abdirashid Abdullahi Osman PWDA [email protected] 907735581 5 Abshir Bashir Isse DRC [email protected] 907780907 6 Said Arshe Ahmed CARE [email protected] 907799710 7 Ahmed said Salaad NRC [email protected] 907795829 8 Said Mohamed Warsame SEDO [email protected] 907798446 9 Mohamed Abdiqadir Jama CARE [email protected] 906798053 10 Mohamed Ali Harbi SHILCON [email protected] 907638045 Agenda Items 1. Introduction and Open remarks among the members. 2. Review of the last meeting action points 3. PWDA updates for the floods affected water sources in Bari and Sanaag 4. Updates of the ongoing Wash interventions as well the projects in the pipeline in Bari and Sanaag. 5. Setting the yearly Wash cluster meeting schedule (Wash Meeting Calendar) 6. Sharing the hygiene and sanitation plans to Bosaso Local Authority 7. AOB Introduction and Opening remarks The WASH cluster chair opened and welcomed the participants to the WASH Cluster meeting in CARE Bosasso office and then an introduction between the participants was flowed and then the meeting agenda was outlined. Review of the last meeting action points The action points from the last meeting was reviewed. 1. PWDA will share the updates and Data of list of water sources in Bari and sanaag Regions to the Cluster. -

Roots for Good Governance

DIALOGUE FOR PEACE Somali Programme Roots for Good Governance Establishing the Legal Foundations for Local Government in Puntland Garowe, Puntland Phone: (+252 5) 84 4480 Thuraya: +88 216 4333 8170 Galkayo Phone: (+252 5) 85 4200 Thuraya: +88 216 43341184 [email protected] www.pdrc.somalia.org Acknowledgements Editor: Ralph Johnstone, The WordWorks Design and Layout: Cege Mwangi, Arcadia Associates Photographs: © Puntland Development Research Centre Front cover photo: Garowe district council members vote for their mayor in June 2005: the election was overseen by the Islan Issa and took place at the PDRC conference hall Back cover photo: Puntland President Adde Musa (second from left) and Vice President, Hassan Daahir (far left) enjoy a light moment with other senior dignitaries during the launch of the Puntland Reform programme in April 2006 at the PDRC conference hall in Garowe. In the background are PDRC research coordinator Ali Farah and Puntland journalists This report was produced by the Puntland Development Research Centre and Interpeace and represents exclusively their own views. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the contributing donors and should not be relied upon as a statement of the contributing donors or their services. The contributing donors do not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor do they accept responsibility for any use made thereof. 2 Roots for Goods Governance Contents November 2006 Introduction to the Dialogue for Peace ..................................................................................... -

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki

S.No Region Districts 1 Awdal Region Baki District 2 Awdal Region Borama District 3 Awdal Region Lughaya District 4 Awdal Region Zeila District 5 Bakool Region El Barde District 6 Bakool Region Hudur District 7 Bakool Region Rabdhure District 8 Bakool Region Tiyeglow District 9 Bakool Region Wajid District 10 Banaadir Region Abdiaziz District 11 Banaadir Region Bondhere District 12 Banaadir Region Daynile District 13 Banaadir Region Dharkenley District 14 Banaadir Region Hamar Jajab District 15 Banaadir Region Hamar Weyne District 16 Banaadir Region Hodan District 17 Banaadir Region Hawle Wadag District 18 Banaadir Region Huriwa District 19 Banaadir Region Karan District 20 Banaadir Region Shibis District 21 Banaadir Region Shangani District 22 Banaadir Region Waberi District 23 Banaadir Region Wadajir District 24 Banaadir Region Wardhigley District 25 Banaadir Region Yaqshid District 26 Bari Region Bayla District 27 Bari Region Bosaso District 28 Bari Region Alula District 29 Bari Region Iskushuban District 30 Bari Region Qandala District 31 Bari Region Ufayn District 32 Bari Region Qardho District 33 Bay Region Baidoa District 34 Bay Region Burhakaba District 35 Bay Region Dinsoor District 36 Bay Region Qasahdhere District 37 Galguduud Region Abudwaq District 38 Galguduud Region Adado District 39 Galguduud Region Dhusa Mareb District 40 Galguduud Region El Buur District 41 Galguduud Region El Dher District 42 Gedo Region Bardera District 43 Gedo Region Beled Hawo District www.downloadexcelfiles.com 44 Gedo Region El Wak District 45 Gedo -

Maternal Nutrition Knoweldge, Infant Feeding Practices and Young Child Nutrition: a Case of Bosaso District, Somalia

MATERNAL NUTRITION KNOWELDGE, INFANT FEEDING PRACTICES AND YOUNG CHILD NUTRITION: A CASE OF BOSASO DISTRICT, SOMALIA MARIAM BASHIR ISMAIL, BSc. (Education) (East Africa University, Somalia) A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN APPLIED HUMAN NUTRITION DEPARTMENT OF FOOD SCIENCE, NUTRITION AND TECHNOLOGY FACULTY OF AGRICULTURE UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI 2020 DECLARATION This Dissertation is my original work and has not been presented for a degree in any other University Sign………………… Date 2/11/2020 Mariam Bashir Ismail This dissertation has been submitted for examination with our approval as university supervisors Dr Sophia Ngala Department of Food Science, Nutrition and Technology, University of Nairobi Signed………………………… Date 2/11/2020 Dr Angela Andago Department of Food Science, Nutrition and Technology, University of Nairobi Signed: ………………… Date: November 3rd, 2020 ii DECLARATION OF ORIGINALITY FORM Name of Student: Mariam Bashir Ismail Registration Number: A56/11702/2018 College: College of Agriculture and Veterinary Sciences Faculty/School/Institute: Agriculture Department: Food Science, Nutrition and Technology Course Name: Masters of Science in Applied Human Nutrition Title of the work: MATERNAL NUTRITION KNOWELDGE, INFANT FEEDING PRACTICES AND YOUNG CHILD NUTRITION: A CASE OF BOSASO DISTRICT, SOMALIA DECLARATION 1. I understand what Plagiarism is and I am aware of the University’s policy in this regard. 2. I declare that this is my original dissertation and has not been submitted elsewhere for examination, award of a degree or publication. Where other people’s work or my own work has been used, this has properly been acknowledged and referenced in accordance with the University of Nairobi’s requirements. -

Pillars of Peace

International Peacebuilding Alliance Garowe, Puntland Alliance internationale pour la consolidation de la paix Phone: (+252 5) 84 4480 • Thuraya: +88 216 4333 8170 Alianza Internacional para la Consolidación de la Paz Galkayo Satellite Office Interpeace Regional Office for Eastern and Central Africa Phone: (+252 5) 85 4200 • Thuraya: +88 216 43341184 T +254(0) 20 3862 840/ 2 • F +254(0) 20 3862 845 P.O.Box 14520 – Nairobi, Kenya 00800 [email protected] www.interpeace.org www.pdrcsomalia.org PILLARS OF PEACE SOMALI PROGRAMME In partnership with the United Nations Puntland Note: Mapping the Foundations of Peace Puntland Note: This publication was made possible through the generous contributions and support from: Puntland Note: Mapping the Foundations of Peace Challenges to Security and Rule of Law, Democratisation Process and Devolution of Power to Local Authorities Denmark Schweizerische Eidgenossenschaft Confederation suisse Confédérazione Svizzera Confederaziun svizra Swiss Confederation European Commission Garowe, November 2010 P ILLARS OF P EACE Somali Programme Puntland Note: Mapping the Foundations of Peace Challenges to Security and Rule of Law, Democratisation Process and Devolution of Power to Local Authorities Garowe, November 2010 i Pillars of Peace - Somali Programme Puntland Note: Mapping the Foundations of Peace Pillars of Peace - Somali Programme ii Acknowledgements This research document was made possible by the joint effort and partnership of the Puntland Development Research Center (PDRC) and the International Peacebuilding Alliance (Interpeace). PDRC would like to thank the Puntland stakeholders who actively participated and substantially contributed to the discussions, interviews, community consultations and analysis of the research output. Special thanks also go to the peer reviewers who, looking at the document from the outside, constructively and attentively reviewed the content and form of this document. -

Maternal Health Outcomes in a Post-War

Maternal Health Outcomes in a Post-war Context: Analysis of Trends, Inequities in Social Determinants of Health and Progress Towards UHC in Somalia Jamila Aden PhD Candidacy Proposal Health Cluster 15072021 • Supervisors: AProf. Delia Hendrie • Co-supervisor: Dr. Judith Daire • Chairperson: AProf. Richard Norman Inequalities in Maternal Health Outcomes ▪ Globally, 295,000 women died in 2017 ➢ 94% of these deaths occur in LMICs o Two thirds of maternal deaths occur in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) ▪ Lifetime risk of maternal mortality Background ➢ 1 in 36 in SSA ➢ 1 in 4,900 in high income countries ▪ Somalia has third highest maternal mortality ratio in the world ➢ 733 maternal death per 100,000 live births International Calls for Reducing Maternal Health Inequalities 1948 1978 1987 1994 Universal Alma-Ata Safe Cairo International Declaration for Conference on Declaration of achieving “Health Motherhood Population and Human Rights for All” Conference Development (ICPD) SM conference marked the start of the Safe Motherhood Initiative (SMI) to reduce maternal mortality to 50% by the year 2000 International Calls for Reducing Maternal Health Inequalities 1995 2000 2005 2008 2015 th Fourth Beijing 58 World Health Commission Millennium Assembly on Social Sustainable International Developme Development Resolution on Determinant Conference nt Goals Goals (MDGs) Universal Health s of Health (SDGs) on Women Coverage ( UHC) (CSDH) SDGs: established a new and ambitious agenda for maternal health. SDG 3 specific to health CSDH: raised awareness of how the conditions in which people are targets include reducing born, grow, live, work, and age shape global health challenges. maternal mortality; and UHC: focus on universal access to needed healthcare services of UHC (greater access to good quality to the entire population without undue financial health services, financial hardship. -

Read the Full Report and Analysis of Feedback From

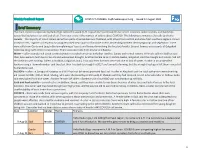

Weekly Feedback Report CONTACT ADDRESS: [email protected] Issued:12 August 2021 Brief Summary The main concerns expressed by Radio Ergo callers this week (5-11 August 2021) continued to be locusts invasions, water scarcity, and hardships caused by food price rises and lack of aid. There was a rise in the number of callers about COVID19. The following summarises the calls by theme. Locusts – the majority of locust callers came from parts of Somaliland and Puntland, with others from central and a few from southern regions. Callers in Marodi-Jeh, Togdher and especially Sanag described new swarms of invasive insects descending on them destroying crops and vegetation. There were calls from Qardo and Laag in Bari complaining of locusts and larvae diminishing the livestock fodder. Several farmers across parts of Galgadud called wanting swift control intervention. There were also calls from Jowhar and Baidoa. Water – callers complained about continuing water scarcity from areas including Togdher, Sanag, and central regions. A female caller in Badhan said their lives were on hold due to locusts and widespread drought. Another female caller in Bahdo-Gaabo, Galgadud, said the drought and locusts had left the livestock with nothing. Callers in Budbud, Galgadud, and L. Juba said their livestock were sick due to lack of water. A caller in an unspecified location using a Hormud number said they lost their livestock to drought in 2017 and turned to farming, but this drought had again left them in need of humanitarian aid. Aid/IDPs – callers in Sanag and Hargeisa said WFP had not delivered promised food aid. -

1 Project Name UN Joint Programme on Local Governance And

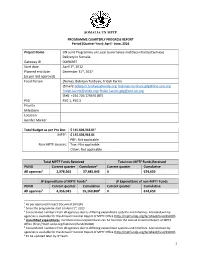

SOMALIA UN MPTF PROGRAMME QUARTERLY PROGRESS REPORT Period (Quarter-Year): April - June, 2016 Project Name UN Joint Programme on Local Governance and Decentralized Services Delivery in Somalia. Gateway ID 00096397 Start date April 1st, 2012 Planned end date December 31st, 2017 (as per last approval) Focal Person (Name): Bobirjan Turdiyev; Fridah Karimi (Email): [email protected]; [email protected] [email protected]; [email protected] (Tel): +254 706 179676 (BT) PSG PSG 1, PSG 5 Priority Milestone Location Gender Marker Total Budget as per Pro Doc $ 145,608,918.811 MPTF: $ 145,608,918.81 PBF: Not applicable Non MPTF sources: Trac: Not applicable Other: Not applicable Total MPTF Funds Received Total non-MPTF Funds Received PUNO Current quarter Cumulative2 Current quarter Cumulative All agencies3 2,978,563 57,485,845 0 674,659 JP Expenditure of MPTF Funds4 JP Expenditure of non-MPTF Funds PUNO Current quarter Cumulative Current quarter Cumulative All agencies5 4,356,041 55,160,8086 0 674,659 1 As per approved Project Document (JPLGII) 2 Since the programme start on April 1st, 2013 3 Consolidated numbers from all agencies due to differing expenditure systems and timelines. A breakdown by agencies is available for the Annual Financial Report of MPTF Office (http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/4SO00) 4 Uncertified expenditures. Certified annual expenditures can be found in the Annual Financial Report of MPTF Office (http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/4SO00) 5 Consolidated numbers from all agencies due to differing expenditure systems and timelines. A breakdown by agencies is available for the Annual Financial Report of MPTF Office (http://mptf.undp.org/factsheet/fund/4SO00) 6 To be updated later by JP Team. -

KAP Study REPORT

Puntland IDP’s Knowledge, Attitude and Practices (KAP) SURVEY on Child Health, Nutrition, Education, water, Sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) FINAL REPORT November 2020 i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The study intended to understand the level of knowledge, attitude and practice (KAP) of IDPs communities in Puntland on WASH facilities, education, protection, and Child Health and Nutrition management services. The objective of this KAP study was to examine the IDP communities’ level of understanding, perceptions and daily practices toward programs mentioned above to evaluate the impact of the previous interventions and the effectiveness of their implementation approaches of the services provided to these communities in general and mainly those supported by UNICEF. The outcome of this study will provide benchmark values of the indicators for WASH, child health and nutrition education, protection programs to the governmental social services delivery authorities, UNICEF and other humanitarian partners to better monitor changes in the living conditions of these vulnerable communities. The study findings will also be used as a tool to inform future program planning, as well as, to measure the progress of current programming in the operational areas in Puntland. To achieve the survey objectives, this report addresses key questions regarding the benchmark values for indicators of health, nutrition, education, WASH and protection projects, with collected data providing baseline, mid-line and end-line values depending on the specific project. The sample unit was determined to be households. A sample size of 840 households was calculated based on the target survey population of 451,55 households in the selected Towns. Sample size for each cluster was determined independently using a 95 % confidence level and 5 % margin of error.