Situational Analysis of Fgm/C Stakeholders and Interventions in Somalia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grouped by Cluster

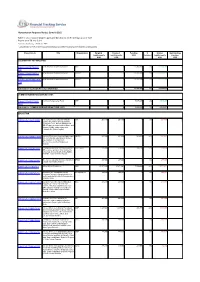

Humanitarian Response Plan(s): Somalia 2015 Table E: List of appeal projects (grouped by Cluster), with funding status of each Report as of 28-Sep-2021 http://fts.unocha.org (Table ref: R##) Compiled by OCHA on the basis of information provided by donors and recipient organizations. Project Code Title Organization Original Revised Funding % Unmet Outstanding requirements requirements USD Covered requirements pledges USD USD USD USD CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED SOM-15/SNYS/78452/ to be allocated to specific projects WFP 0 0 15,200,048 0% -15,200,048 0 561 SOM-15/SNYS/78471/ to be allocated to specific projects UNHCR 0 0 22,776,204 0% -22,776,204 0 120 SOM-15/SNYS/78658/R/ to be allocated to specific projects UNICEF 0 0 13,712,399 0% -13,712,399 0 124 Sub total for CLUSTER NOT YET SPECIFIED 0 0 51,688,651 0% -51,688,651 0 COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) SOM-15/SNYS/77965/ Common Humanitarian Fund CHF 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 7622 Sub total for COMMON HUMANITARIAN FUND (CHF) 0 0 9,595,257 0% -9,595,257 0 EDUCATION SOM-15/E/71574/8380 Increasing Access & Quality of Basic JCC 201,150 201,150 0 0% 201,150 0 Literacy for Children and Adults from Vulnerable, Poor, Women Headed and IDP / Returness Households in Bu'ale and Salagle (Middle Jubba region) and Celbarde-Ato (Bakool region) SOM-15/E/71608/14579 Improved Protective Learning Spaces and FENPS 451,400 451,400 289,999 64% 161,401 0 Access to Quality Education for School Age Children in Humanitarian Emergencies and Conflict Areas in Somalia SOM-15/E/71628/5660 Emergency education for crises-affected -

Download Full Report

2016 Elections in Somalia - The Rise of the New Somali Women's Political Movements The Somali Institute for Development and Research Analysis (SIDRA) Garowe, Puntland State of Somalia Cell Phone: +252-907-794730 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.sidrainstitute.org This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial License (CC BY-NC 4.0) Attribute to: Somali Institute for Development & Research Analysis 2016 A note of Appreciation Many Somali women freely provided their time to take part in the surveys, focus group discussions and interviews for this study and thereby helping us collect quality data that allowed us to make sound scientific analysis. Without their contributions, this study would not have reached its findings. This study was self funded by SIDRA and would not have materialized without the sacrifice of keeping aside other cost to allocate resources for this study. Finally, this study would not have come to be without the tireless efforts of SIDRA staff through the direction of Sahro Koshin, SIDRA Head of Programmes and leadership of Guled Salah, SIDRAs Executive Director. Many other people supported this study in different ways and made it a success. SIDRA whole heartedly appreciates all these people. Page | 2 2016 Elections in Somalia - The Rise of the New Somali Women's Political Movements Table of content EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................................................6 CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION AND -

Assessment Report 2011

ASSESSMENT REPORT 2011 PHASE 1 - PEACE AND RECONCILIATION JOIN- TOGETHER ACTION For Galmudug, Himan and Heb, Galgaduud and Hiiraan Regions, Somalia Yme/NorSom/GSA By OMAR SALAD BSc (HONS.) DIPSOCPOL, DIPGOV&POL Consultant, in collaboration with HØLJE HAUGSJÅ (program Manager Yme) and MOHAMED ELMI SABRIE JAMALLE (Director NorSom). 1 Table of Contents Pages Summary of Findings, Analysis and Assessment 5-11 1. Introduction 5 2. Common Geography and History Background of the Central Regions 5 3. Political, Administrative Governing Structures and Roles of Central Regions 6 4. Urban Society and Clan Dynamics 6 5. Impact of Piracy on the Economic, Social and Security Issues 6 6. Identification of Possibility of Peace Seeking Stakeholders in Central Regions 7 7. Identification of Stakeholders and Best Practices of Peace-building 9 8. How Conflicts resolved and peace Built between People Living Together According 9 to Stakeholders 9. What Causes Conflicts Both locally and regional/Central? 9 10. Best Practices of Ensuring Women participation in the process 9 11. Best Practices of organising a Peace Conference 10 12. Relations Between Central Regions and Between them TFG 10 13. Table 1: Organisation, Ownership and Legal Structure of the 10 14. Peace Conference 10 15. Conclusion 11 16. Recap 11 16.1 Main Background Points 16.2 Recommendations 16.3 Expected Outcomes of a Peace Conference Main and Detailed Report Page 1. Common geography and History Background of Central Regions 13 1.1 Overview geographical and Environmental Situation 13 1.2 Common History and interdependence 14 1.3 Chronic Neglect of Central Regions 15 1.4 Correlation Between neglect and conflict 15 2. -

Going Global: Islamist Competition in Contemporary Civil Wars

Security Studies,25:353–384,2016 Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0963-6412 print / 1556-1852 online DOI: 10.1080/09636412.2016.1171971 Going Global: Islamist Competition in Contemporary Civil Wars AISHA AHMAD The global landscape of modern jihad is highly diverse and wrought with conflict between rival Islamist factions. Within this inter- Islamist competition, some factions prove to be more robust and durable than others. This research proposes that the adoption of a global identity allows an Islamist group to better recruit and expand their domestic political power across ethnic and tribal divisions without being constrained by local politics. Islamists that rely on an ethnic or tribal identity are more prone to group fragmentation, whereas global Islamists are better able to retain group cohesion by purging their ranks of dissenters. To examine these two processes, I present original field research and primary source analysis to ex- amine Islamist in-fighting in Somalia from 2006–2014 and then expand my analysis to Iraq and Syria, Pakistan, and Mali. GOING GLOBAL: ISLAMIST COMPETITION IN CONTEMPORARY CIVIL WARS The global landscape of modern jihad is highly diverse and wrought with internal competition.1 In Pakistan, factions within the Tehrik-i-Taliban (TTP) movement have repeatedly clashed over the past decade, splintering into Downloaded by [University of Toronto Libraries] at 07:31 05 July 2016 multiple powerful jihadist groups. In northern Mali, the ethnic Tuareg re- bellion has also fractured, leading some Islamist factions to build strong ties to al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM).2 More recently, the Aisha Ahmad is an Assistant Professor at the University of Toronto. -

OARE Participating Academic Institutions

OARE Participating Academic Institutions Filter Summary Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Bamyan Bamyan University Charikar Parwan University Cheghcharan Ghor Institute of Higher Education Ferozkoh Ghor university Gardez Paktia University Ghazni Ghazni University Herat Rizeuldin Research Institute And Medical Hospital HERAT UNIVERSITY Health Clinic of Herat University Ghalib University Jalalabad Nangarhar University Afghanistan Rehabilitation And Development Center Alfalah University 19-Dec-2017 3:14 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 1 of 194 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan Kabul Ministry of Higher Education Afghanistan Biodiversity Conservation Program Afghanistan Centre Cooperation Center For Afghanistan (cca) Ministry of Transport And Civil Aviation Ministry of Urban Development Afghanistan Research and Evaluation Unit (AREU) Social and Health Development Program (SHDP) Emergency NGO - Afghanistan French Medical Institute for children, FMIC Kabul University. Central Library American University of Afghanistan Kabul Polytechnic University Afghanistan National Public Health Institute, ANPHI Kabul Education University Allied Afghan Rural Development Organization (AARDO) Cheragh Medical Institute Kateb University Afghan Evaluation Society Prof. Ghazanfar Institute of Health Sciences Information and Communication Technology Institute (ICTI) Ministry of Public Health of Afghanistan Kabul Medical University Isteqlal Hospital 19-Dec-2017 3:14 PM Prepared by Payment, HINARI Page 2 of 194 Country City Institution Name Afghanistan -

TCC Trains Somali Research Network Members in Data Analysis and Presentation

26 September 2016 PRESS RELEASE TCC Trains Somali Research Network Members in Data Analysis and Presentation Training Centre in Communication (TCC) trained Somali Research Education Network (SomaliREN) members in Data Analysis and Presentation in Mogadishu, Somalia. The training ran from 27-29 September, where participants learned the following ; The theory and practice of presenting data in graphical form, The basic principles of economy, clarity, and integrity, Old types of graphs to avoid, new graph types: dot plot, scatterplot matrix, conditional plot, How to design effective graphs, How to use R Statistical software graphical analysis and presentation, How to use SPSS Statistical software graphical analysis and presentation and How to use STATA Statistical software graphical analysis and presentation. 26 participants from Amoud University ,Benadir University ,University of Burao, Puntland State University, East Africa University, SIMAD University, Mogadishu University ,University of Hargeisa, Gollis University, City University, Heritage Institute, Nugaal University, Kismayo University and Galkayo University, took part in the training. The Consortium of Training Institutions Training Centre in Communication The Training Centre in Communication (TCC) is a self-sustainable Trust created through private public partnership and has its headquarters at the University of Nairobi, Kenya. It is the first Centre in Africa that builds capacity in Science Communication for research institutes and universities, through training and guidance in implementation of communication strategy. TCC has successfully managed to build capacity in Science Communication in Western, Eastern and Southern Africa since 2004, before it was registered as a Trust and created a partnership with University of Nairobi in 2007. More information about Training Center in Communication can be accessed at www.tcc-africa.org. -

The State of the Higher Education Sector in Somalia South-Central, Somaliland, and Puntland Regions

The State of the Higher Education Sector in Somalia South-Central, Somaliland, and Puntland Regions June 2013 Published in 2013 by the Heritage Institute for Policy Studies Amira Hotel Road, KM5 Junction, Mogadishu, Somalia The Heritage Institute for Policy Studies The Heritage Institute for Policy Studies is an independent, non-partisan, non- profit policy research and analysis institute based in Mogadishu, Somalia. As Somalia’s first think tank, it aims to inform and influence public policy through empirically based, evidence-informed analytical research, and to promote a culture of learning and research. Cover: Students at the University of Somalia Photograph by Omar Faruk Rights: Copyright © The Heritage Institute for Policy Studies Cover image © Omar Faruk Text published under Creative Commons Licence Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative www.creativecommons.org/licences/by/nc-nd/3.0. Available for free download at www.heritageinstitute.org Table of Contents Chapter 1: Executive summary 1 1.1 Findings 2 Chapter 2: Methodology 3 2.1 Survey of HEIs 3 2.2 Site selection and sampling 4 2.3 Research questions, data collection tools, and analysis 4 2.4 Data limitation 4 Chapter 3: Background of the education sector in Somalia 5 3.1 Pre-colonial and colonial education 5 3.2 Post-independence education 5 3.3 Education post-1991 6 Chapter 4: Current state of the higher education sector 8 4.1 Growth patterns 8 4.2 Number of students 8 4.3 Number of lecturers 9 4.4 Qualification of lecturers 9 4.5 Faculty numbers and types 10 4.6 Distribution -

Land Use Planning Guidelines for Somaliland 2009

Land Use Planning Guidelines for Somaliland Project Report No L-13 March 2009 Somalia Water and Land Information Management Ngecha Road, Lake View. P.O Box 30470-00100, Nairobi, Kenya. Tel +254 020 4000300 - Fax +254 020 4000333, Email: [email protected] Website: http//www.faoswalim.org. Funded by the European Union and implemented by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and the SWALIM Project concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This document should be cited as follows: Venema, J.H., Alim, M., Vargas, R.R., Oduori, S and Ismail, A. 2009. Land use planning guidelines for Somaliland. Technical Project Report L-13. FAO-SWALIM, Nairobi, Kenya. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms ............................................................................................ v Acknowledgments ..........................................................................................vi ABOUT THE GUIDELINES................................................................................ vii 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................... 1 1.1 What is land use planning?................................................................. 1 1.2 Recent -

SOMALIA RAINFALL and FLOODS UPDATE 02 May 2021

SOMALIA RAINFALL and FLOODS UPDATE 02 May 2021 Due to climate change and its associated impacts Somalia is now recording more wet and dry weather events, often with disastrous consequences for the people facing such extremes. It has become even more difficult to predict such sequential events. Currently, more than 80 percent of the country is facing drought conditions in the mid of the primary Gu rainy season. Yet, flash floods have been reported in the last two days following heavy and sporadic rains in Somaliland. In addition, limited climate change adaptive capacities has led to irresponsible socio- economic practices like cutting of river banks to extract irrigation waters, further exposing the communities to climate hazards. For instance, riverine flooding due to open river banks near Baarey and Moyko villages has been reported in Jowhar within Middle Shabelle region. With current climate models predicting extreme temperatures and rainfall in the future within the region, the country is likely to continue experiencing frequent flood and drought events with likely consequences of affecting untold numbers of people, taxing economies, disrupting food production, creating unrest and prompting migrations. FLOODS AND RAINS UPDATE The Gu rains continued to spread across most parts of the country with Somaliland and Puntland experiencing moderate to heavy rains over the last week. Other areas in central and southern regions recorded light to moderate rains. The Ethiopian highlands received moderate rains within the last week. Since 25 May 2021, most parts of Somaliland have been receiving moderate to heavy rains. Localized flash floods caused by the heavy rainfall were reported on 01 May 2021 in parts of Hargeisa district. -

Export Agreement Coding (PDF)

Peace Agreement Access Tool PA-X www.peaceagreements.org Country/entity Somalia Region Africa (excl MENA) Agreement name Declaration of National Commitment (Arta Declaration) Date 05/05/2000 Agreement status Multiparty signed/agreed Interim arrangement No Agreement/conflict level Intrastate/intrastate conflict ( Somali Civil War (1991 - ) ) Stage Framework/substantive - partial (Multiple issues) Conflict nature Government/territory Peace process 87: Somalia Peace Process Parties The Transnational Government of Somalia Third parties [Note: Several references to the international community] Description Agreement outlines the responsibilities of the Transitional National Assembly, the election of the Chief Justice, the roles of the President and Prime Minister, particularly, the limitations of power of the President. It includes 17-points of binding principles. The Annexes include a ceasefire; a plan of reconstrution and recovery; and the foundations for representation of the Somali population in the TNA and the national dialogue. Agreement document SO_000505_Declaration of national commitment.pdf [] Groups Children/youth No specific mention. Disabled persons No specific mention. Elderly/age No specific mention. Migrant workers No specific mention. Racial/ethnic/national Substantive group [Summary] Contains substantive consideration of inter-group representation in the Transitional National Assembly. Page 1, • Representation in the Conference and in the "Transitional National Assembly" shall be on the basis of local constituencies (regional /clan mix) Page 3, TOWARD THIS END WE ... 8. pledge to place national interest above clan self interest, personal greed and ambitions Page 6, ANNEX IV BASE OF REPRESENTATION IN THE ... WHAT TO GUARD AGAINST • It must be stressed that representation based on clan affiliations or the assumed strength or importance of certain clan, including the size of territories presumed or traditional belonging to certain clans, would only succeed in perpetuating or reinforcing the division of the nation. -

Afmadow District Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia

Afmadow district Detailed Site Assessment Lower Juba Region, Somalia Introduction Location map The Detailed Site Assessment (DSA) was triggered in the perspectives of different groups were captured2. KI coordination with the Camp Coordination and Camp responses were aggregated for each site. These were then Management (CCCM) Cluster in order to provide the aggregated further to the district level, with each site having humanitarian community with up-to-date information on an equal weight. Data analysis was done by thematic location of internally displaced person (IDP) sites, the sectors, that is, protection, water, sanitation and hygiene conditions and capacity of the sites and the humanitarian (WASH), shelter, displacement, food security, health and needs of the residents. The first round of the DSA took nutrition, education and communication. place from October 2017 to March 2018 assessing a total of 1,843 sites in 48 districts. The second round of the DSA This factsheet presents a summary of profiles of assessed sites3 in Afmadow District along with needs and priorities of took place from 1 September 2018 to 31 January 2019 IDPs residing in these sites. As the data is captured through assessing a total of 1778 sites in 57 districts. KIs, findings should be considered indicative rather than A grid pattern approach1 was used to identify all IDP generalisable. sites in a specific area. In each identified site, two key Number of assessed sites: 14 informants (KIs) were interviewed: the site manager or community leader and a women’s representative, to ensure Assessed IDP sites in Afmadow4 Coordinates: Lat. 0.6, Long. -

Somalia Hunger Crisis Response.Indd

WORLD VISION SOMALIA HUNGER RESPONSE SITUATION REPORT 5 March 2017 RESPONSE HIGHLIGHTS 17,784 people received primary health care 66,256 people provided with KEY MESSAGES 24,150,700 litres of safe drinking water • Drought has led to increased displacement education. In Somaliland more than 118 of people in Somalia. In February 2017 schools were closed as a result of the alone, UNHCR estimates that up to looming famine. 121,000 people were displaced. • Urgent action at this stage has a high • There is a sharp increase in the number of chance of saving over 300,000 children Acute Water Diarrhoea (AWD/cholera) who are acutely malnourished as well cases. From January to March, 875 AWD as over 6 million people facing possible cases and 78 deaths were recorded in starvation across the country. 22,644 Puntland, Somaliland and Jubaland. • Despite encouraging donor contributions, • There is an urgent need to scale up the Somalia humanitarian operational people provided with support for health interventions in the plan is less than 20% funded (UNOCHA, South West State (SWS) especially FTS, 7th March 2017). Approximately 5,917 in districts that have been hard hit by US$825 million is required to reach 5.5 NFI kits outbreaks of Acute Watery Diarrhoea million Somalis facing possible famine until (AWD). Only few agencies have funding June 2017. to support access to health care services. • More than 6 million people or over 50% • According to Somaliland MOH, high of Somalia’s population remain in crisis cases of measles, diarrhea and pneumonia and face possible famine if aid does not have been reported since November as match the scale of need between now main health complications caused by the and June 2017.