ALEXANDER Morrls and the SAULTEAUX: the CONTEXT and MAKING of TREATY THREE, 1869-73

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba

Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba February 2020 Authors: Jeff Smith Karen Rempel Heather Duncan with contributions from: Valerie McInnes Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba February 2020 Submitted to: Indigenous Services Canada Rolling River School Division Erickson Collegiate Institute Erickson Elementary School Rolling River First Nation Submitted by: Karen Rempel, Ph.D. Director, Centre for Aboriginal and Rural Education Studies (CARES) Faculty of Education Brandon University Written by: Jeff Smith Karen Rempel Heather Duncan With contributions from: Valerie McInnes Table of Contents Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Manitoba Schools Executive Summary 1 Introduction 4 Process 5 Context of the Evaluators 6 Evaluation Framework 7 Program Evaluation Question 7 Program Evaluation Methodology 8 Data Collection and Assessment Inventory 8 Student Surveys 8 School Context Teacher Interviews 8 Data collection and analysis 9 Organization of this Report 9 Part 1: Introduction 10 Challenges of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education 10 Educational Achievement Gaps 11 Addressing Achievement Gaps 11 Context of Erickson, Manitoba Schools 12 Rolling River First Nation 12 Challenges for Erickson, Manitoba Schools in the Rolling River School Division 13 Cultural Proficiency: A Rolling River School Division Priority 13 Indigenization through the Application of Mino-Pimaatisiwin -

The Obsolete Theory of Crown Unity in Canada and Its Relevance to Indigenous Claims

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2015 The Obsolete Theory of Crown Unity in Canada and Its Relevance to Indigenous Claims Kent McNeil Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: (2015) 20 Review of Constitutional Studies 1-29 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works Part of the Indian and Aboriginal Law Commons Repository Citation McNeil, Kent, "The Obsolete Theory of Crown Unity in Canada and Its Relevance to Indigenous Claims" (2015). Articles & Book Chapters. 2777. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works/2777 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. The Obsolete Theory of Crown Unity in Canada and Its Relevance to Indigenous Claims Kent McNeil* This article examines the application of the L'uteur de cet article examine l'pplication theory ofthe unity ofthe Crown in Canada in de la theorie de Punite de la Couronne the context of Indigenous peoples. It reveals a au Canada dans le contexte des peuples consistent retreat by the courtsfrom acceptance autochtones. I rivile une retraite constante of the theory in the late nineteenth century to de la part des tribunaux de lipprobation de rejection ofit in the secondhalfofthe twentieth la theorie a la fin du dix-neuvidme sicle a century. This evolution ofthe theory' relevance, son rejet au cours de la deuxidme moiti du it is argued, is consistent with Canada federal vingtidme sidcle. -

Cluster 2: a Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government

A Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government by Ted Longbottom C urrent t opiCs in F irst n ations , M étis , and i nuit s tudies Cluster 2: a profound ambivalence: First nations, Métis, and inuit relations with Government Setting the Stage: Economics and Politics by Ted Longbottom L earninG e xperienCe 2.1: s ettinG the s taGe : e ConoMiCs and p oLitiCs enduring understandings q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples share a traditional worldview of harmony and balance with nature, one another, and oneself. q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples represent a diversity of cultures, each expressed in a unique way. q Understanding and respect for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples begin with knowledge of their pasts. q Current issues are really unresolved historical issues. q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples want to be recognized for their contributions to Canadian society and to share in its successes. essential Questions Big Question How would you describe the relationship that existed among Indigenous nations and between Indigenous nations and the European newcomers in the era of the fur trade and the pre-Confederation treaties? Focus Questions 1. How did Indigenous nations interact? 2. How did First Nations’ understandings of treaties differ from that of the Europeans? 3. What were the principles and protocols that characterized trade between Indigenous nations and the traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company? 4. What role did Indigenous nations play in conflicts between Europeans on Turtle Island? Cluster 2: a profound ambivalence 27 Background Before the arrival of the Europeans, First Peoples were self-determining nations. -

The Rose Collection of Moccasins in the Canadian Museum of Civilization : Transitional Woodland/Grassl and Footwear

THE ROSE COLLECTION OF MOCCASINS IN THE CANADIAN MUSEUM OF CIVILIZATION : TRANSITIONAL WOODLAND/GRASSL AND FOOTWEAR David Sager 3636 Denburn Place Mississauga, Ontario Canada, L4X 2R2 Abstract/Resume Many specialists assign the attribution of "Plains Cree" or "Plains Ojibway" to material culture from parts of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. In fact, only a small part of this area was Grasslands. Several bands of Cree and Ojibway (Saulteaux) became permanent residents of the Grasslands bor- ders when Reserves were established in the 19th century. They rapidly absorbed aspects of Plains material culture, a process started earlier farther west. This paper examines one such case as revealed by footwear. Beaucoup de spécialistes attribuent aux Plains Cree ou aux Plains Ojibway des objets matériels de culture des régions du Manitoba ou de la Saskatch- ewan. En fait, il n'y a qu'une petite partie de cette région ait été prairie. Plusieurs bandes de Cree et d'Ojibway (Saulteaux) sont devenus habitants permanents des limites de la prairie quand les réserves ont été établies au XIXe siècle. Ils ont rapidement absorbé des aspects de la culture matérielle des prairies, un processus qu'on a commencé plus tôt plus loin à l'ouest. Cet article examine un tel cas comme il est révélé par des chaussures. The Canadian Journal of Native Studies XIV, 2(1 994):273-304. 274 David Sager The Rose Moccasin Collection: Problems in Attribution This paper focuses on a unique group of eight pair of moccasins from southern Saskatchewan made in the mid 1880s. They were collected by Robert Jeans Rose between 1883 and 1887. -

'-Sp-Sl'-' University Dottawa Ecole Des Gradues

001175 ! / / -/ '-SP-SL'-' UNIVERSITY DOTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES JOSEPH DUBUC ROLE AND VIEWS OF A FRENCH CANADIAN IN MANITOBA l870-191l+ by Sister Maureen of the Sacred Heart, S.N.J.M. (M.M. McAlduff) Thesis presented to the Faculty of Arts of the University of Ottawa through the Department of History as partial ful fillment of the requirewents for the degree of Master of Arts ,<^S3F>a^ . LIBRARIES » Winnipeg, Manitoba, 1966 UNIVERSITY OF OTTAWA SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES UMI Number: EC55664 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform EC55664 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 UNIVERSITE D'OTTAWA ECOLE DES GRADUES ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis was prepared under the guidance of Dr. Alfred Vanasse of the Department of History. The writer wishes to thank him for his helpful direction, doubly appreciated since it had to be given entirely by mail. The writer also expresses gratitude to Archivist Hartwell Bowsfield and Assistant Archivist Regis Bennett of the Provincial Archives of Manitoba; to the Chancery staff of the Archiepiscopal Archives of St. -

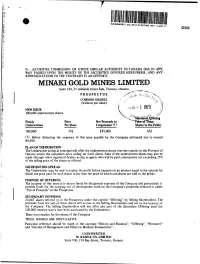

Prospectus of Minaki Gold Mines

S2609NW892, 83.321. B l GJfSL BAY (LAKE J 010 Nv SECURITIES COMMISSION OR OTHER SIMILAR AUTHORITY IN CANADA HAS IN ANY, WAY PASSED UPON THE MERITS OF THE SECURITIES OFFERED HEREUNDER, AND ANY REPRESENTATION TO THE CONTRARY IS AN OFFENCE. MINAKI GOLD MINES LIMITED Suite 520,25 Adelaide Street East, Toronto, Ontario PROSPECTUS COMMON SHARES (without par value) NEW ISSUE 100,000 underwritten shares. Firmly Price Net Proceeds to ~*"Prter ofTfiese Underwritten Per Share Corporation d) Shares to the Public 100,000 35^ S35,000 (1) Before deducting the expenses of this issue payable by the Company estimated not to exceed S4.500. PLAN OF DISTRIBUTION The Underwriter acting as principal will offer the underwritten shares over-the-counter in the Province of Ontario within the maximum price ceiling set forth above. Sales of the underwritten shares may also be made through other registered dealers acting as agents who will be paid commissions not exceeding 259k of the selling price of the shares so offered. DISTRIBUTION SPREAD The Underwriter may be said to realize the profit before expenses in an amount equal to the amount by which the price paid for such shares is less than the price of which said shares are sold to the public. PURPOSE OF OFFERING The purpose of this Issue is to secure funds for the general expenses of the Company and particularly tc provide funds for the carrying out of development work on the Company©s properties referred to under "Use of Proceeds" in this Prospectus. SECONDARY OFFERING 23,887 shares referred to in the Prospectus under the caption "Offering" by Selling Shareholders. -

Treaty 5 Treaty 2

Bennett Wasahowakow Lake Cantin Lake Lake Sucker Makwa Lake Lake ! Okeskimunisew . Lake Cantin Lake Bélanger R Bélanger River Ragged Basin Lake Ontario Lake Winnipeg Nanowin River Study Area Legend Hudwin Language Divisi ons Cobham R Lake Cree Mukutawa R. Ojibway Manitoba Ojibway-Cree .! Chachasee R Lake Big Black River Manitoba Brandon Winnipeg Dryden !. !. Kenora !. Lily Pad !.Lake Gorman Lake Mukutawa R. .! Poplar River 16 Wakus .! North Poplar River Lake Mukwa Narrowa Negginan.! .! Slemon Poplarville Lake Poplar Point Poplar River Elliot Lake Marchand Marchand Crk Wendigo Point Poplar River Poplar River Gilchrist Palsen River Lake Lake Many Bays Lake Big Stone Point !. Weaver Lake Charron Opekamank McPhail Crk. Lake Poplar River Bull Lake Wrong Lake Harrop Lake M a n i t o b a Mosey Point M a n i t o b a O n t a r i o O n t a r i o Shallow Leaf R iver Lewis Lake Leaf River South Leaf R Lake McKay Point Eardley Lake Poplar River Lake Winnipeg North Etomami R Morfee Berens River Lake Berens River P a u i n g a s s i Berens River 13 ! Carr-Harris . Lake Etomami R Treaty 5 Berens Berens R Island Pigeon Pawn Bay Serpent Lake Pigeon River 13A !. Lake Asinkaanumevatt Pigeon Point .! Kacheposit Horseshoe !. Berens R Kamaskawak Lake Pigeon R !. !. Pauingassi Commissioner Assineweetasataypawin Island First Nation .! Bradburn R. Catfish Point .! Ridley White Beaver R Berens River Catfish .! .! Lake Kettle Falls Fishing .! Lake Windigo Wadhope Flour Point Little Grand Lake Rapids Who opee .! Douglas Harb our Round Lake Lake Moar .! Lake Kanikopak Point Little Grand Pigeon River Little Grand Rapids 14 Bradbury R Dogskin River .! Jackhead R a p i d s Viking St. -

Winter Fishing on Lake of the Woods and the Rainy River

LAKE OF THE WOODS and RAINY RIVER INFORMATION Lake of the Woods is a border water, shared with the Canadian provinces of Manitoba and Ontario. The Minnesota portion of Lake of the Woods has several regulations that differ from the general statewide regulations. Please take the time to familiarize yourself with these differences to avoid inadvertently violating any regulations. Make sure that you note the effective dates of the various regulations outlined in this summary. Regulations that apply to Lake of the Woods during the summer are different than those listed here. Minnesota Waters Fishing Regulation Summary Walleye and Sauger Northern Pike Lake of the Woods All Northern Pike from 30 through 40 inches must be released immediately, and only one Northern (May 9, 2020 – April 14, 2021) Pike over 40 inches may be possessed. The possession limit for Northern Pike is three. The Walleye/Sauger aggregate limit is six (no more than four can be Walleye). Walleye from 19.5 There is no closed season for Northern Pike on Lake through 28 inches must be immediately released. of the Woods or the Rainy River. Only one Walleye over 28 inches total length may be possessed. Yellow Perch Rainy River and Four Mile Bay The bag limit is 20 Yellow Perch per day, with 40 in possession. (May 9, 2020 – February 28, 2021) There is no closed season for Yellow Perch. Same as Lake of the Woods Lake Sturgeon (March 1, 2021 – April 14, 2021) Lake Sturgeon cannot be harvested from Oct. 1, 2020 through Apr. 23, 2021. Catch and release Catch and release fishing is allowed during this time fishing is allowed during this time period. -

Lake of the Woods Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report

Lake of the Woods Watershed Monitoring and Assessment Report March 2016 Authors The MPCA is reducing printing and mailing costs MPCA Lake of the Woods Watershed Report by using the Internet to distribute reports and Team: information to wider audience. Visit our April Andrews, Benjamin Lundeen, Nathan website for more information. Sather, Jesse Anderson, Bruce Monson, Cary MPCA reports are printed on 100 percent post- Hernandez, Sophia Vaughan, Jane de Lambert, consumer recycled content paper David Duffey, Shawn Nelson, Andrew Streitz, manufactured without chlorine or chlorine Stacia Grayson derivatives. Contributors / acknowledgements Minnesota Department of Natural Resources Minnesota Department of Health Minnesota Department of Agriculture Lake of the Woods county Soil and Water Conservation Districts Roseau county Soil and Water Conservation Districts The Red Lake Nation Project dollars provided by the Clean Water Fund (from the Clean Water, Land and Legacy Amendment) Minnesota Pollution Control Agency 520 Lafayette Road North | Saint Paul, MN 55155-4194 | 651-296-6300 | 800-657-3864 | Or use your preferred relay service. | [email protected] This report is available in alternative formats upon request, and online at www.pca.state.mn.us. Document number: wq-ws3-09030009 Contents Executive summary ................................................................................................................................................ 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks©

Sagkeeng First Nation: Developmental Impacts and the Perception of Environmental Health Risks© by Brenda Elias John D. O’Neil Annalee Yassi Benita Cohen Department of Community Health Sciences University of Manitoba For additional copies of this report please contact CAHR office at 204-789-3250 April 1997 SAGKEENG FIRST NATION: DEVELOPMENT IMPACTS AND THE PERCEPTION OF ENVIRONMENTAL HEALTH RISKS FINAL REPORT BRENDA ELIAS JOHN O’NEIL ANNALEE YASSI BENITA COHEN University of Manitoba Northern Health Research Unit Occupational and Environmental Health Unit Department of Community Health Sciences Faculty of Medicine (c) April 1997 Funding provided by the National Health Research and Development Program NHRDP Project No. 6607-1620-63 1 1.0 Introduction In 1988, a critical assessment was conducted on how governments and industry address potential health impacts of industrial developments in northern regions of Canada. The Canadian Environmental Assessment Research Council (CEARC) held several regional workshops across Canada to foster discussion on northern and Aboriginal understandings of environmental health issues. Many broad recommendations emerged: ∗ the health of a community should be understood before a development project is underway; ∗ the impacts of an existing industrial site on a community over time should be understood by actually studying whether there is industry-related diseases (such as cancer or lung problems) developing in that community; ∗ a communication approach that provides scientific information on contaminants to northern communities should be developed; ∗ a constructive and respectful way of understanding what northerners consider to be a danger to their health should be developed. This study is a critical response to these recommendations. It examines the cultural basis of risk perception and the importance of local knowledge in changing the assessment and management of health risks. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

Horse Traders, Card Sharks and Broken Promises: the Contents of Treaty #3 a Detailed Analysis December 21, 2011

Horse Traders, Card Sharks and Broken Promises: The Contents of Treaty #3 A Detailed Analysis December 21, 2011 Many people have studied, written about and talked about Canada's 1873 Treaty #3 with the Saulteaux Anishnaabek over 55,000 square miles west of Lake Superior. We are not the first nor the last. We are not legal experts or historians. Being grandmothers, we have skills of observation and commitment to future generations. Our views are our own. We don't claim to represent any community, tribe or nation though we are confident many people agree with us. We do think everyone in this land has a duty to know about the history that has brought us to this time. Our main purpose here is to prompt discussion of these important matters. Treaty 3 was a definitive one that shaped the terms of the next several Treaties 4 - 7. Revisions to 1 and 2 also resulted from it. The later treaties used Treaty 3 as a role model. For the 1905 Treaty 9 with the James Bay Cree, this was difficult because the Dominion Government was trying to pay even less for the Cree territory than they had for the Saulteaux Ojibwe territory. The Cree were fully aware of what had gone on. In our view, a Treaty is something that must be reviewed, renewed and reconfirmed at regular intervals in order for it to maintain its authority with the signatories. If anyone fails to adhere to the Treaty terms, then it becomes a broken Treaty no longer valid. Can a broken jug hold water? INTENT OF THE TREATIES - A Program to Steal the Land by Conciliatory Methods (Note#4,5) In this article, we examine some of the key elements of Treaty #3 aka the North-West Angle Treaty.