Cluster 2: a Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Note Abstract

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 382 427 RC 020 085 RUTH(:.: Candline, Mary TITLE Stages of Learning: Building a Native Curriculum. Teachers' Guide, Student Activities--Part I, Research Unit--Part II. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. Literacy Office. PUB DATE [92] NOTE I38p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use - Instructional Materials (For Learner) (051) -- Guides - Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *American Indian Education; Biographies; *Canada Natives; Canadian Studies; *Civics; Curriculum; Elementary Secondary Education; Federal Indian Relationship; Foreign Countries; Instructional Materials; Interviews; Language Arts; Learning Activities; *Library Skills; Politics; Public Officials; Reading Materials; Research Papers (Students); *Research Skills; Research Tools; Sculpture; Student Research; Teaching Guides; Vocabulary Development; Writing Assignments IDENTIFIERS Crazy Horse; *Manitoba ABSTRACT This language arts curriculum developed for Native American students in Manitoba (Canada) consists of a teachers' guide, a student guide, and a research unit. The curriculum includes reading selections and learning activities appropriate for the different reading levels of both upper elementary and secondary students. The purpose of the unit is for students to develop skills in brainstorming, biography writing, letter writing, note taking, researching, interviewing, spelling, and vocabulary. Reading selections focus on Elijah Harper, an Ojibway Cree Indian who helped defeat the Meech Lake Accord, an amendment to Canada's Constitution proposed in 1987. The Meech Lake Accord would have transferred power from the federal government to provincial governments and would have failed to take into account the interests of Natives, women, and minorities. The curriculum also includes reading selections on the creation of the Aboriginal Justice Inquiry and on Crazy Horse. -

Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba

Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba February 2020 Authors: Jeff Smith Karen Rempel Heather Duncan with contributions from: Valerie McInnes Final Report of the Program Evaluation of the Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Schools, Manitoba February 2020 Submitted to: Indigenous Services Canada Rolling River School Division Erickson Collegiate Institute Erickson Elementary School Rolling River First Nation Submitted by: Karen Rempel, Ph.D. Director, Centre for Aboriginal and Rural Education Studies (CARES) Faculty of Education Brandon University Written by: Jeff Smith Karen Rempel Heather Duncan With contributions from: Valerie McInnes Table of Contents Action Research for Mino-Pimaatisiwin in Erickson Manitoba Schools Executive Summary 1 Introduction 4 Process 5 Context of the Evaluators 6 Evaluation Framework 7 Program Evaluation Question 7 Program Evaluation Methodology 8 Data Collection and Assessment Inventory 8 Student Surveys 8 School Context Teacher Interviews 8 Data collection and analysis 9 Organization of this Report 9 Part 1: Introduction 10 Challenges of First Nations, Métis and Inuit Education 10 Educational Achievement Gaps 11 Addressing Achievement Gaps 11 Context of Erickson, Manitoba Schools 12 Rolling River First Nation 12 Challenges for Erickson, Manitoba Schools in the Rolling River School Division 13 Cultural Proficiency: A Rolling River School Division Priority 13 Indigenization through the Application of Mino-Pimaatisiwin -

Treaty 5 Treaty 2

Bennett Wasahowakow Lake Cantin Lake Lake Sucker Makwa Lake Lake ! Okeskimunisew . Lake Cantin Lake Bélanger R Bélanger River Ragged Basin Lake Ontario Lake Winnipeg Nanowin River Study Area Legend Hudwin Language Divisi ons Cobham R Lake Cree Mukutawa R. Ojibway Manitoba Ojibway-Cree .! Chachasee R Lake Big Black River Manitoba Brandon Winnipeg Dryden !. !. Kenora !. Lily Pad !.Lake Gorman Lake Mukutawa R. .! Poplar River 16 Wakus .! North Poplar River Lake Mukwa Narrowa Negginan.! .! Slemon Poplarville Lake Poplar Point Poplar River Elliot Lake Marchand Marchand Crk Wendigo Point Poplar River Poplar River Gilchrist Palsen River Lake Lake Many Bays Lake Big Stone Point !. Weaver Lake Charron Opekamank McPhail Crk. Lake Poplar River Bull Lake Wrong Lake Harrop Lake M a n i t o b a Mosey Point M a n i t o b a O n t a r i o O n t a r i o Shallow Leaf R iver Lewis Lake Leaf River South Leaf R Lake McKay Point Eardley Lake Poplar River Lake Winnipeg North Etomami R Morfee Berens River Lake Berens River P a u i n g a s s i Berens River 13 ! Carr-Harris . Lake Etomami R Treaty 5 Berens Berens R Island Pigeon Pawn Bay Serpent Lake Pigeon River 13A !. Lake Asinkaanumevatt Pigeon Point .! Kacheposit Horseshoe !. Berens R Kamaskawak Lake Pigeon R !. !. Pauingassi Commissioner Assineweetasataypawin Island First Nation .! Bradburn R. Catfish Point .! Ridley White Beaver R Berens River Catfish .! .! Lake Kettle Falls Fishing .! Lake Windigo Wadhope Flour Point Little Grand Lake Rapids Who opee .! Douglas Harb our Round Lake Lake Moar .! Lake Kanikopak Point Little Grand Pigeon River Little Grand Rapids 14 Bradbury R Dogskin River .! Jackhead R a p i d s Viking St. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

Horse Traders, Card Sharks and Broken Promises: the Contents of Treaty #3 a Detailed Analysis December 21, 2011

Horse Traders, Card Sharks and Broken Promises: The Contents of Treaty #3 A Detailed Analysis December 21, 2011 Many people have studied, written about and talked about Canada's 1873 Treaty #3 with the Saulteaux Anishnaabek over 55,000 square miles west of Lake Superior. We are not the first nor the last. We are not legal experts or historians. Being grandmothers, we have skills of observation and commitment to future generations. Our views are our own. We don't claim to represent any community, tribe or nation though we are confident many people agree with us. We do think everyone in this land has a duty to know about the history that has brought us to this time. Our main purpose here is to prompt discussion of these important matters. Treaty 3 was a definitive one that shaped the terms of the next several Treaties 4 - 7. Revisions to 1 and 2 also resulted from it. The later treaties used Treaty 3 as a role model. For the 1905 Treaty 9 with the James Bay Cree, this was difficult because the Dominion Government was trying to pay even less for the Cree territory than they had for the Saulteaux Ojibwe territory. The Cree were fully aware of what had gone on. In our view, a Treaty is something that must be reviewed, renewed and reconfirmed at regular intervals in order for it to maintain its authority with the signatories. If anyone fails to adhere to the Treaty terms, then it becomes a broken Treaty no longer valid. Can a broken jug hold water? INTENT OF THE TREATIES - A Program to Steal the Land by Conciliatory Methods (Note#4,5) In this article, we examine some of the key elements of Treaty #3 aka the North-West Angle Treaty. -

"It Was Only a Treaty"

"IT WAS ONLY A TREATY" TREATY 11 ACCORDING TO THE DENE OF THE MACKENZIE VALLEY Revised for The Dene Nation and The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples Rene M.J. Lamothe April, 1996 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY "It Was Only A Treaty" provides some basic concepts about Treaty 11 from a Dene perspective. The paper sets out cultural parameters of Dene life by providing information on key social, economic, political and spiritual aspects of Dene life with the intention of providing readers with the historical and legal context in which the Dene live. Through the presentation of the context of Dene life, the paper sets the parameters which limit Dene decision making with regards to the land and relationships with non-Dene. Some of the information may be viewed by academic interests to be outside the scope of what they consider "sound knowledge" about the Dene. The information, however, is provided from within the context of Dene experience, much of which, being of a spiritual nature, is not readily available to the "outside" academic. This information is also intended, in part, to set the stage for the non-Dene to better understand the social, political and economic conditions in play in Dene society in 1921. Understanding the context from which the Dene approached the Crown's Treaty Party is fundamental to understanding the Dene version of Treaty 11. The paper explores government interests in the territory covered by Treaty 11. Although this section is very limited in its' scope and does not provide conclusive evidence about the motives of government, it provides information on land surveys which took place in Dene territory before Treaty was made, as well as bringing to light some of the political and economic pressures which have been at play within the Euro-Canadian/American public since contact. -

Directory – Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba

Indigenous Organizations in Manitoba A directory of groups and programs organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis people Community Development Corporation Manual I 1 INDIGENOUS ORGANIZATIONS IN MANITOBA A Directory of Groups and Programs Organized by or for First Nations, Inuit and Metis People Compiled, edited and printed by Indigenous Inclusion Directorate Manitoba Education and Training and Indigenous Relations Manitoba Indigenous and Municipal Relations ________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION The directory of Indigenous organizations is designed as a useful reference and resource book to help people locate appropriate organizations and services. The directory also serves as a means of improving communications among people. The idea for the directory arose from the desire to make information about Indigenous organizations more available to the public. This directory was first published in 1975 and has grown from 16 pages in the first edition to more than 100 pages in the current edition. The directory reflects the vitality and diversity of Indigenous cultural traditions, organizations, and enterprises. The editorial committee has made every effort to present accurate and up-to-date listings, with fax numbers, email addresses and websites included whenever possible. If you see any errors or omissions, or if you have updated information on any of the programs and services included in this directory, please call, fax or write to the Indigenous Relations, using the contact information on the -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

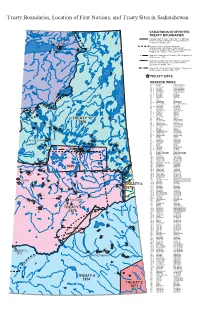

Treaty Boundaries Map for Saskatchewan

Treaty Boundaries, Location of First Nations, and Treaty Sites in Saskatchewan VARIATIONS IN DEPICTED TREATY BOUNDARIES Canada Indian Treaties. Wall map. The National Atlas of Canada, 5th Edition. Energy, Mines and 229 Fond du Lac Resources Canada, 1991. 227 General Location of Indian Reserves, 225 226 Saskatchewan. Wall Map. Prepared for the 233 228 Department of Indian and Northern Affairs by Prairie 231 224 Mapping Ltd., Regina. 1978, updated 1981. 232 Map of the Dominion of Canada, 1908. Department of the Interior, 1908. Map Shewing Mounted Police Stations...during the Year 1888 also Boundaries of Indian Treaties... Dominion of Canada, 1888. Map of Part of the North West Territory. Department of the Interior, 31st December, 1877. 220 TREATY SITES RESERVE INDEX NO. NAME FIRST NATION 20 Cumberland Cumberland House 20 A Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 B Pine Bluff Cumberland House 20 C Muskeg River Cumberland House 20 D Budd's Point Cumberland House 192G 27 A Carrot River The Pas 28 A Shoal Lake Shoal Lake 29 Red Earth Red Earth 29 A Carrot River Red Earth 64 Cote Cote 65 The Key Key 66 Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 66 A Keeseekoose Keeseekoose 68 Pheasant Rump Pheasant Rump Nakota 69 Ocean Man Ocean Man 69 A-I Ocean Man Ocean Man 70 White Bear White Bear 71 Ochapowace Ochapowace 222 72 Kahkewistahaw Kahkewistahaw 73 Cowessess Cowessess 74 B Little Bone Sakimay 74 Sakimay Sakimay 74 A Shesheep Sakimay 221 193B 74 C Minoahchak Sakimay 200 75 Piapot Piapot TREATY 10 76 Assiniboine Carry the Kettle 78 Standing Buffalo Standing Buffalo 79 Pasqua -

Land Entitlement Under Treaty 8 951

LAND ENTITLEMENT UNDER TREATY 8 951 LAND ENTITLEMENT UNDER TREATY 8 ROBERT METCS' AND CHRISTOPHER G. DEVLIN" This article provides an analysis of the land Cet article analyse /es dispositions sur /es droits entitlement provisions of Treaty 8 as they relate to fonciers du Traile 8 relalivement au traile federal current federal treaty land entitlement ([LE) policy actue/ sur la po/ilique sur /es droils fonciers el le and to the judgment in Lac La Ronge. The authors jugement du Lac La Ronge. Les auleurs delerminen/ identify and analyze significant textual, contextual, el analysent des differences lexluel/es. conlex/uelles el and historical differences between Treaty 8 and !he hisloriques considerables en/re le Traite 8 el /es sepl previous seven numbered Trealies. On !he basis of lraites precedenls. Comple /enu de celle analyse, /es !hat analysis, !he au/hors advance various proposals au/eursfont plusieurs propositions visanl a appuyer in support of a principled policy approach lo une demarche de polilique molivee dans le bu/ determining the existence and extenl of the d 'etablir I 'existence et la portee des obligations obligalions placed upon the Crown by Treaty 8 and imposees a la Couronne par le Traite 8 et /es the land enlitlemenl provisions contained therein. dispositions sur /es droits fanciers qu 'ii conlient. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................. 952 II. INTERPRETATION OF TREATY 8 ................................. 953 A. THE LAND ENTITLEMENT PROVISIONS OF TREATY 8 .......................................... 953 B. LEGAL PRINCIPLES APPLICABLE TO THE INTERPRETATION OF TREATIES ............................. 955 C. THE LAC LA RONG£ DECISION ............................. 958 D. APPLICATION OF LEGAL PRINCIPLES TO TREATY 8 ......................................... -

Acknowledging Land and People

* ACKNOWLEDGING LAND AND PEOPLE Smith’s Landing First Nation TREATY 4 Dene Tha’ Mikisew First Nation MNA Cree Lake REGION 6 Nation TREATY 6 Athabasca Athabasca Beaver First Nation Chipewyan TREATY 7 Little Red River First Nation Cree Nation TREATY 8 Tallcree MNA First REGION 1 Nation Fort McKay TREATY 10 PADDLE PRAIRIE MNA REGION 5 First Nation Métis Settlements Loon River Peerless/ Lubicon First Nation Trout Lake Fort McMurray Lake Nation MNA Regional Zones First Nation Woodland Cree Métis Nation of First Nation Whitefi sh Lake Fort McMurray Alberta (MNA) First Nation Bigstone Cree First Nation (Atikameg) Association Nation PEAVINE Cities and Towns GIFT LAKE Chipewyan Kapawe’no Duncan’s Prairie First First Nation First Nation Kapawe’no Nation Sucker Creek First Nation Grande First Nation Lesser Slave Lake Sawridge Horse Lake Prairie First Nation First Nation EAST PRAIRIE Swan Heart Lake River First Nation** Sturgeon Lake Driftpile First BUFFALO LAKE Nation Cree Nation First Nation Beaver Cold KIKINO Lake Cree Lake First Nation Nations Whitefi sh Lake First MNA N a t i o n ( G o o d fi s h ) Kehewin ELIZABETH TREATY 4 First Nation Frog REGION 4 Alexander First Nation Saddle Lake Michel First Lake First Alexis Nakota Sioux First Nation Cree Nation Nation TREATY 6 Nation FISHING Edmonton Paul First Nation LAKE TREATY 7 Papaschase First Nation Enoch Cree Nation (Edmonton) Ermineskin Cree Nation TREATY 8 Louis Bull Tribe Jasper Samson MNA Montana Cree Nation Cree Nation TREATY 10 REGION 2 Métis Settlements O’Chiese First Nation Sunchild First -

Christianity, Missionaries and Plains Cree Politics, 1850S–1870S by Tolly Bradford History Department, Concordia University of Edmonton

Christianity, Missionaries and Plains Cree Politics, 1850s–1870s by Tolly Bradford History Department, Concordia University of Edmonton eginning in the 1990s, much of the historiography of life and their own political aspirations. In outlining these missionary-Indigenous interaction in 19th-century patterns of responses, I emphasize that this divisiveness BCanada and the British Empire has explored how was not rooted in differing religious views per se, but rather Indigenous leaders made very active and conscious use in different beliefs about whether the missionary was an of the missionaries and Christianity in the framing and asset or a threat to a leader’s ability to provide for, and shaping of their politics, particularly in their political maintain their own authority within, their band. In making interactions with the colonial state.1 This interpretive shift represented a revision of older histories that had tended to [I]n the years immediately preceding Treaty ignore Indigenous agency in the history of encounters with missionaries, and instead either uncritically celebrated, Six (1876) ... it appears there was significant or categorically condemned, missionaries for their division amongst Cree leaders about the value ability to shape and assimilate Indigenous societies into of missionaries. Christian-European cultural frameworks.2 While there “ is no consensus in this revisionist approach about how Indigenous communities used Christianity on their this argument I highlight something generally overlooked own terms, most scholars would now agree with what in scholarship about the prairie west: that even before Elizabeth Elbourne, in her study of the Six Nations, argues: treaties, reserves, and residential schooling, Christianity that Indigenous communities and leaders were able to and missionaries were shaping the contours of Cree politics.