The Effects of Orientalist Discourse in Literature and Memoir on the Prosecution of the Great Caucasian War, 1817-1864" (2013)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Applied Analysis of Social Criticism Theory on the Base of Russian Literary Works

Journal of Literature and Art Studies, February 2018, Vol. 8, No. 2, 239-248 doi: 10.17265/2159-5836/2018.02.009 D DAVID PUBLISHING Applied Analysis of Social Criticism Theory on the Base of Russian Literary Works Leyla Hacızade Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey Lermontov, who lived and gave masterpieces in 19th century known as golden age of Russian literature, had thought on conflict of good and bad throughout his life and reflected it to his works. In the most part of his works, there are struggles of good with bad. This analysis should be done in concept of social determinism, so it must be done in the light of social criticism theory. In his work “Beyond Good and Evil” Nietzche asked some questions like “What is good? What is bad?”, too. In our study we’ll try to analyze the famous philosopher’s opinions in Lermontov’s “Masquerade” by reviewing these opinions in the concept of social criticism. This study has an interesting point of view like analyzing the place of a Russian writer in the parallel of Europian literature. Keywords: Good, Bad, Conflict, Social Determinism, Concept Introduction 19th century is a golden age of Russian literature, for the reason that in this age many well-known writers and critics lived and gave masterpieces. Some of these famous writers and critics are: Karamzin, Zhukovksy, Krylov, Griboyedov, Pushkin, Gogol, Lermontov, Turgenev, Nekrasov, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov, Chernyshevsky, Belinsky, Dobroliubov, etc. Like the other fields related with human, literature has also evolved in line with supply and demand. If there weren’t any fruitful fields, there couldn’t grow well any plant. -

The Education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov The

Agata Strzelczyk DOI: 10.14746/bhw.2017.36.8 Department of History Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Abstract This article concerns two very different ways and methods of upbringing of two Russian tsars – Alexander the First and Nicholas the First. Although they were brothers, one was born nearly twen- ty years before the second and that influenced their future. Alexander, born in 1777 was the first son of the successor to the throne and was raised from the beginning as the future ruler. The person who shaped his education the most was his grandmother, empress Catherine the Second. She appoint- ed the Swiss philosopher La Harpe as his teacher and wanted Alexander to become the enlightened monarch. Nicholas, on the other hand, was never meant to rule and was never prepared for it. He was born is 1796 as the ninth child and third son and by the will of his parents, Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Fyodorovna he received education more suitable for a soldier than a tsar, but he eventually as- cended to the throne after Alexander died. One may ask how these differences influenced them and how they shaped their personalities as people and as rulers. Keywords: Romanov Children, Alexander I and Nicholas I, education, upbringing The education of Alexander and Nicholas Pavlovich Romanov Among the ten children of Tsar Paul I and Tsarina Maria Feodorovna, two sons – the oldest Alexander and Nicholas, the second youngest son – took the Russian throne. These two brothers and two rulers differed in many respects, from their characters, through poli- tics, views on Russia’s place in Europe, to circumstances surrounding their reign. -

Eugene Miakinkov

Russian Military Culture during the Reigns of Catherine II and Paul I, 1762-1801 by Eugene Miakinkov A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History and Classics University of Alberta ©Eugene Miakinkov, 2015 Abstract This study explores the shape and development of military culture during the reign of Catherine II. Next to the institutions of the autocracy and the Orthodox Church, the military occupied the most important position in imperial Russia, especially in the eighteenth century. Rather than analyzing the military as an institution or a fighting force, this dissertation uses the tools of cultural history to explore its attitudes, values, aspirations, tensions, and beliefs. Patronage and education served to introduce a generation of young nobles to the world of the military culture, and expose it to its values of respect, hierarchy, subordination, but also the importance of professional knowledge. Merit is a crucial component in any military, and Catherine’s military culture had to resolve the tensions between the idea of meritocracy and seniority. All of the above ideas and dilemmas were expressed in a number of military texts that began to appear during Catherine’s reign. It was during that time that the military culture acquired the cultural, political, and intellectual space to develop – a space I label the “military public sphere”. This development was most clearly evident in the publication, by Russian authors, of a range of military literature for the first time in this era. The military culture was also reflected in the symbolic means used by the senior commanders to convey and reinforce its values in the army. -

Download Full Text In

The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS Future Academy ISSN: 2357-1330 https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.03.02.133 SCTCMG 2018 International Scientific Conference «Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism» SEMANTIC TRANSFORMATIONS OF RUSSIAN CULTURAL HERITAGE IN THE CONSCIOUSNESS OF SOVIET ERA Ye.V. Somova (a)*, N.V. Svitenko (b), Ye.A. Zhirkova (с), L.N. Ryaguzova (d), M.V. Yuryeva (e) *Corresponding author (a) Kuban State University, Stavropolskaya, 149, Krasnodar, Russia (b) Kuban State University, Stavropolskaya, 149, Krasnodar, Russia (c) Kuban State University, Stavropolskaya, 149, Krasnodar, Russia, (d) Kuban State University, Stavropolskaya, 149, Krasnodar, Russia (e) Kuban State University, Stavropolskaya, 149, Krasnodar, Russia, Abstract The paper analyzes the main trends in implementation of intertextual dialog between the 19th and the 20th century in conditions of globalization process in the Soviet culture on the material of reception of M. Yu. Lermontov's oeuvre. Various aspects in perception and semantic transformation of classical literary works of M. Yu. Lermontov in multi-ethnic environment are studied, namely: transformation of classics into national mythology, where the poet becomes an eternal image of the Russian literature and an “eternal satellite” of the Russian life. Methodological instrumentarium of intertextual and comparative approach allows juxtaposing the key motifs and images of selected authors, identifying typological correlations and differences between the prevailing principles in artistic thought of various writers, reveal dynamics and peculiarities in perception of the artistic axiology of M. Yu. Lermontov in the social and cultural context of the 20th century and showing the original features of complex, deeply nationally representative artistic world view, whose constants formed a foundation of the archetypal image of a Russian Poet. -

BYRONISM in LERMONTOV's a HERO of OUR TIME by ALAN HARWOOD CAMERON B.A., U N I V E R S I T Y O F C a L G a R Y , 1968 M.A

BYRONISM IN LERMONTOV'S A HERO OF OUR TIME by ALAN HARWOOD CAMERON B.A., University of Calgary, 1968 M.A., University of British Columbia, 1970 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in the Department SLAVONIC STUDIES We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA April, 1974 In presenting this thesis in par ial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the Head of my Department or by his representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver 8, Canada Date Afr, I l0} I f7f ABSTRACT Although Mikhail Lermontov is commonly known as the "Russian Byron," up to this point no examination of the Byronic features of A Hero of Our Time, (Geroy nashego vremeni)3 has been made. This study presents the view that, while the novel is much more than a simple expression of Byronism, understanding the basic Byronic traits and Lermontov1s own modification of them is essential for a true comprehension of the novel. Each of the first five chapters is devoted to a scrutiny of the separate tales that make up A Hero of Our Time. The basic Byronic motifs of storms, poses and exotic settings are examined in each part with commentary on some Lermontovian variations on them. -

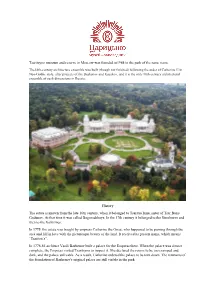

Tsaritsyno Museum and Reserve in Moscow Was Founded In1984 in the Park of the Same Name

Tsaritsyno museum and reserve in Moscow was founded in1984 in the park of the same name. The18th-century architecture ensemble was built (though not finished) following the order of Catherine II in Neo-Gothic style, after projects of the Bazhenov and Kazakov, and it is the only 18th-century architectural ensemble of such dimensions in Russia. History The estate is known from the late 16th century, when it belonged to Tsaritsa Irina, sister of Tsar Boris Godunov. At that time it was called Bogorodskoye. In the 17th century it belonged to the Streshnevs and then to the Galitzines. In 1775, the estate was bought by empress Catherine the Great, who happened to be passing through the area and fell in love with the picturesque beauty of the land. It received its present name, which means “Tsaritsa’s”. In 1776-85 architect Vasili Bazhenov built a palace for the Empress there. When the palace was almost complete, the Empress visited Tsaritsyno to inspect it. She declared the rooms to be too cramped and dark, and the palace unlivable. As a result, Catherine ordered the palace to be torn down. The remnants of the foundation of Bazhenov's original palace are still visible in the park. In 1786, Matvey Kazakov presented new architectural plans, which were approved by Catherine. Kazakov supervised the construction project until 1796 when the construction was interrupted by Catherine's death. Her successor, Emperor Paul I of Russia showed no interest in the palace and the massive structure remained unfinished and abandoned for more than 200 years, until it was completed and extensively reworked in 2005-07. -

Traditional Social Organisation of the Chechens

Traditional social organisation of the Chechens Patrilineages with domination and social control of elder men. The Chechens have a kernel family called dëzel1 (дёзел), consisting of a couple and their children. But this kernel family is not isolated from other relatives. Usually married brethren settled in the neighbourhood and cooperated. This extended family is called “ts'a” (цIа - “men of one house”); the word is etymologically connected with the word for “hearth”. The members of a tsa cooperated in agriculture and animal husbandry. Affiliated tsa make up a “neqe” or nek´´e (некъий - “people of one lineage”). Every neqe has a real ancestor. Members of a neqe can settle in one hamlet or in one end of a village. They can economically cooperate. The next group of relatives is the “gar“ (гар - “people of one branch“). The members of a gar consider themselves as affiliated, but this can be a mythological affiliation. The gars of some Chechen groups function like taips (s. below). Taip The main and most famous Chechen social unit is the “taip” (tajp, tayp, тайп) A taip is a group of persons or families cooperating economically and connected by patrilinear consanguineous affiliation. The members of a taip have equal rights2. In the Russian and foreign literature taips are usually designated as “clans”. For the Chechens the taip is a patrilinear exogam group of descendants of one ancestor. There were common taip rules and/ore features3 including: • The right of communal land tenure; • Common revenge for murder of a taip member or insulting -

The Circassian Thistle: Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy's Khadzhi

ABSTRACT THE CIRCASSIAN THISTLE: TOLSTOY’S KHADZHI MURAT AND THE EVOLVING RUSSIAN EMPIRE by Eric M. Souder The following thesis examines the creation, publication, and reception of Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy’s posthumous novel, Khadzhi Murat in both the Imperial and Soviet Russian Empire. The anti-imperial content of the novel made Khadzhi Murat an incredibly vulnerable novel, subjecting it to substantial early censorship. Tolstoy’s status as a literary and cultural figure in Russia – both preceding and following his death – allowed for the novel to become virtually forgotten despite its controversial content. This thesis investigates the absorption of Khadzhi Murat into the broader canon of Tolstoy’s writings within the Russian Empire as well as its prevailing significance as a piece of anti-imperial literature in a Russian context. THE CIRCASSIAN THISTLE: TOLSTOY’S KHADZHI MURAT AND THE EVOLVING RUSSIAN EMPIRE A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Miami University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History by Eric Matthew Souder Miami University Oxford, Ohio 2014 Dr. Stephen Norris Dr. Daniel Prior Dr. Margaret Ziolkowski TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………1 Chapter I - The Tolstoy Canon: The Missing Avar……………………………………………….2 Chapter II – Inevitable Editing: The Publication and Censorship of Khadzhi Murat………………5 Chapter III – Historiography and Appropriation: The Critical Response to Khadzhi Murat……17 Chapter IV – Conclusion………………………………………………………………………...22 Afterword………………………………………………………………………………………..24 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..27 ii Introduction1 In late-October 1910, Lev Nikolaevich Tolstoy died at Astopovo Station, approximately 120 miles from his family estate at Yasnaya Polyana in the Tula region of the Russian Empire. -

{PDF EPUB} Lay of Tsar Ivan Vassilyevich His Young Oprichnik And

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Lay of Tsar Ivan Vassilyevich His Young Oprichnik and the Stouthearted Merchant Kalashnikov by Mikha Lay of Tsar Ivan Vassilyevich His Young Oprichnik and the Stouthearted Merchant Kalashnikov by Mikhail Lermontov. The freedom loving Russian Romantic poet and author of the novel Geroi nashego vremeni (1840, Hero of Our Time), which had a deep influence on later Russian writers. Lermontov was exiled twice to the Caucasus because of his libertarian verses. He died in a duel like his great contemporary, the poet Aleksandr Pushkin. Mikhail Lermontov was born in Moscow, the son of Yuri Petrovich Lermontov, a poor army officer, and Maria Mikhailovna Lermontova, an heiress to rich estates, who belonged to the prominent Stolypin family. The Lermontovs claimed descent from the Learmonths in Scotland. Maria Mihkailovna died of consumption in 1817; her marriage had lasted barely four years. After her death, Lermontov's father left his son's upbringing to Yelizaveta Alexeyevna Arsenyeva, his wealthy grandmother. In the new home he became the subject of family disputes between his grandmother and father, who was not allowed to participate in the upbringing. Lermontov received an extensive education at home, but it included doubtful aspects: in his childhood he was dressed in a girl's frock to act as a model for a painter. At the age of fourteen Lermontov moved to Moscow, where he entered a boarding school for the sons of the nobility. At the Moscow University he started to write poetry under the influence of Lord Byron, adapting the Byronic cult of personality. One of Lermontov's first loves during this period was Ekaterina Sushkova, who did not reciprocate his feelings. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/115937 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2021-09-27 and may be subject to change. Thomas Keijser The Caucasus Revisited. Development of Semantic Oppositions from Puškin and Lermontov to the Present1 1. Introduction This article investigates the development of the image of the Caucasus in Russian poetry, prose and "lm from the middle of the nineteenth century up to the present day. It focuses on semantic oppositions that recur over time. As Lermontov has played an important role in determining the image of the Caucasus, a selection of his works, which are typically illustrative of these oppositions, will serve as a starting point. The extent to which Lermontov drew inspiration from Puškin will be examined, as well as the way in which the semantic oppositions present in the middle of the nine- teenth century occur in Tolstoj’s works, in the Soviet era and in recent literature and "lm. To Lermontov (1814-1841), the Caucasus was a major source of inspiration. He spent time in the region not only as a child, but was later exiled to that region, the "rst time in 1837 after the publication of his critical poem Smert’ poơta (The Poet’s Death) on the occasion of Puškin’s death. After a duel with a son of the French ambassador, Lermontov was sent to the Caucasus a second time in 1840. -

Law and Familial Order in the Romanov Dynasty *

Russian History 37 (2010) 389–411 brill.nl/ruhi “For the Firm Maintenance of the Dignity and Tranquility of the Imperial Family”: Law and Familial Order in the Romanov Dynasty * Russell E. Martin Westminster College Abstract Th is article examines the Law of Succession and the Statute on the Imperial Family, texts which were issued by Emperor Paul I on April 5,1797, and which regulated the succession to the throne and the structure of the Romanov dynasty as a family down to the end of the empire in 1917. It also analyzes the revisions introduced in these texts by subsequent emperors, focusing particu- larly on the development of a requirement for equal marriage and for marrying Orthodox spouses. Th e article argues that changing circumstances in the dynasty—its rapid increase in numbers, its growing demands on the fi nancial resources of the Imperial Household, its struggle to resist morganatic and interfaith marriages—forced changes to provisions in the Law and Statute, and that the Romanovs debated and reformed the structure of the Imperial Family in the context of the provisions of these laws. Th e article shows how these Imperial House laws served as a vitally important arena for reform and legal culture in pre-revolutionary Russia. Keywords Paul I, Alexander III , Fundamental Laws of Russia , Statute on the Imperial Family , Succession , Romanov dynasty Th e death of Grand Duchess Leonida Georgievna on the night of May 23-24, 2010, garnered more media coverage in Russia than is typical for members of the Russian Imperial house. As the widow of Grand Duke Vladimir Kirillovich (1917-1992), the legitimist claimant to the vacant Russian throne (the fi rst * ) I wish to thank the staff of Hillman Library of the University of Pittsburgh, for their assistance to me while working in the stacks on this project, and Connie Davis, the intrepid interlibrary loan administrator of McGill Library at Westminster College, for her time and help fi nding sources for me. -

M. Iu. Lermontov

Slavistische Beiträge ∙ Band 409 (eBook - Digi20-Retro) Walter N. Vickery M. Iu. Lermontov His Life and Work Verlag Otto Sagner München ∙ Berlin ∙ Washington D.C. Digitalisiert im Rahmen der Kooperation mit dem DFG-Projekt „Digi20“ der Bayerischen Staatsbibliothek, München. OCR-Bearbeitung und Erstellung des eBooks durch den Verlag Otto Sagner: http://verlag.kubon-sagner.de © bei Verlag Otto Sagner. Eine Verwertung oder Weitergabe der Texte und Abbildungen, insbesondere durch Vervielfältigung, ist ohne vorherige schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages unzulässig. «Verlag Otto Sagner» ist ein Imprint der Kubon & Sagner GmbH. Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access 00056058 SLAVISTICHE BEITRÄGE Herausgegeben von Peter Rehder Beirat: Tilman Berger • Walter Breu • Johanna Renate Döring-Smimov Walter Koschmal ■ Ulrich Schweier • Milos Sedmidubsky • Klaus Steinke BAND 409 V erla g O t t o S a g n er M ü n c h en 2001 Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access 00056058 Walter N. Vickery M. Iu. Lermontov: His Life and Work V er la g O t t o S a g n er M ü n c h en 2001 Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access PVA 2001. 5804 ISBN 3-87690-813-2 © Peter D. Vickery, Richmond, Maine 2001 Verlag Otto Sagner Abteilung der Firma Kubon & Sagner D-80328 München Gedruckt auf alterungsbeständigem Papier Bayerisch* Staatsbibliothek Müocfcta Walter N. Vickery - 9783954790326 Downloaded from PubFactory at 01/10/2019 02:27:08AM via free access When my father died in 1995, he left behind the first draft of a manuscript on the great Russian poet and novelist, Mikhail Lermontov.