Appendices Appendix a First Published Report of Prader-Willi Syndrome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Guide to Obesity and the Metabolic Syndrome

A GUIDE TO OBESITY AND THE METABOLIC SYNDROME ORIGINS AND TREAT MENT GEORG E A. BRA Y Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge, USA Boca Raton London New York CRC Press is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC CRC Press Taylor & Francis Group 6000 Broken Sound Parkway NW, Suite 300 Boca Raton, FL 33487-2742 © 2011 by Taylor and Francis Group, LLC CRC Press is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group, an Informa business No claim to original U.S. Government works Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 International Standard Book Number: 978-1-4398-1457-4 (Hardback) This book contains information obtained from authentic and highly regarded sources. Reasonable efforts have been made to publish reliable data and information, but the author and publisher cannot assume responsibility for the valid- ity of all materials or the consequences of their use. The authors and publishers have attempted to trace the copyright holders of all material reproduced in this publication and apologize to copyright holders if permission to publish in this form has not been obtained. If any copyright material has not been acknowledged please write and let us know so we may rectify in any future reprint. Except as permitted under U.S. Copyright Law, no part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or uti- lized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopy- ing, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers. -

The Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases and Disorders

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF lJ z > 0 z Endocrine < I ~ Diseases UJ< I and Disorders UJ ...J '-'- z 0 V'l 1- u '-'-< WILLIAM P ETIT. JR.. M.0. CHRISTINE ADAMEC THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ENDOCRINE DISEASES AND DISORDERS THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF ENDOCRINE DISEASES AND DISORDERS William Petit Jr., M.D. Christine Adamec The Encyclopedia of Endocrine Diseases and Disorders Copyright © 2005 by William Petit Jr., M.D., and Christine Adamec All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Petit, William. The encyclopedia of endocrine diseases and disorders / William Petit Jr., Christine Adamec. p. ; cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8160-5135-6 (hc : alk. paper) 1. Endocrine glands—Diseases—Encyclopedias. [DNLM: 1. Endocrine Diseases—Encyclopedias—English. WK 13 P489ea 2005] I. Adamec, Christine A., 1949– II. Title. RC649.P48 2005 616.4’003—dc22 2004004916 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com. Text and cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB FOF 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

Poster Presentations

______________________________________ P1-d1-164 Adrenals and HPA Axis 1 Arterial hypertension in children: alterations in mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid axis and their impact on pro-inflammatory, endothelial damage, and oxidative stress parameters Carmen Campino1; Rodrigo Bancalari2; Alejandro Martinez-Aguayo2; Poster Presentations Marlene Aglony2; Hernan Garcia2; Carolina Avalos2; Lilian Bolte2; Carolina Loureiro2; Cristian Carvajal1; Lorena Garcia3; Sergio Lavanderos3; Carlos Fardella1 1Pontificia Universidad Catolica, Endocrinology, and Millennium Institute of Immunology and Immunotherapy, Santiago, Chile; 2Pontificia Universidad Catolica, pediatrics, Santiago, Chile; 3Universidad de Chile, School of Chemical Sciences, Santiago, Chile Background and aims: The pathogenesis of arterial hypertension and its impact and determining factors with respect to cardiovascular damage in chil- dren is poorly understood. We evaluated the prevalence of alterations in the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid axes and their impact on pro-inflam- matory, endothelial damage and oxidative stress parameters in hypertensive children. Methods: 306 children (5-16 years old); Group 1: Hypertensives (n=111); Group 2: normotensives with hypertensive parents (n=101); Group 3: normotensives with normotensives parents (n= 95). Fasting blood samples were drawn for hormone measurements (aldosterone, plasma renin activity (PRA), cortisol (F), cortisone (E)); inflammation vari- ______________________________________ ables (hsRCP, adiponectin, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α); endothelial damage (PAI-I, P1-d1-163 Adrenals and HPA Axis 1 MMP9 and MMP2 activities) and oxidative stress (malondialdehyde). Famil- The role of S-palmitoylation of human ial hyperaldosteronism type 1 (FH-1) was diagnosed when aldosterone/PRA ratio >10 was associated with the chimeric CYP11B1/CYP11B2 gene. The glucocorticoid receptor in mediating the non- 11β-HSD2 activity was considered altered when the F/E ratio exceeded the genomic actions of glucocorticoids mean + 2 SD with respect to group 3. -

Obituary Prof. Dr. Ruth Illig

International Journal of Neonatal Screening Obituary Obituary Prof. Dr. Ruth Illig Annette Grüters-Kieslich 1,*, Toni Torresani 2 and Daniel Konrad 3 1 Chief Medical Director and Chairwoman of the Board, Heidelberg University Hospital, Im Neuenheimer Feld 672, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany 2 Former Director Swiss Newborn Screening Laboratory, University Children‘s Hospital, Steinwiesstrasse 75, 8032 Zürich, Switzerland; [email protected] 3 Head of the Department of Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetology, University Children‘s Hospital, Steinwiesstrasse 75, 8032 Zürich, Switzerland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 27 July 2017; Accepted: 28 July 2017; Published: 3 August 2017 On 26 June 2017 Prof. Dr. Ruth Illig peacefully passed away after a life fulfilled with an untiring commitment for children with endocrine diseases. She has been an enthusiastic fighter for the improvement of child health not only in Europe, but also with a global perspective. Ruth Illig was born on 12 November 1924 in Nuremberg, Germany. Her childhood and adolescence in Germany was affected by the Second World War. During the war, she was brought from Germany to Switzerland to recover from the stressful situation and physical weakening. After the war, she spent a significant time of her academic training in Bern and Zurich. Following graduation from medical school she was accepted by Prof. Guido Fanconi for a pediatric residency at the University Children’s Hospital (Kinderspital) Zurich, Switzerland. She was promoted to a fellow and tenure position and worked closely with Prof. Andrea Prader. In these early years, she focused on growth disorders and she established the endocrine laboratory using radioimmunoassays for determination of growth hormone and insulin. -

Pediatric Endocrinology

Books & journals books Adrenal: Fluck, C. E. (ed.) & Miler, W. L. (ed.) . Disorders of the human adrenal cortex. Basel: Karger; 2018. Krieger, D. T. Cushing's syndrome. Berlin: Springer; 1982. Lajic, Svetlana . Molecular analysis of mutated P450c21 in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Stockholm: Department of Women and Child Health Pediatr; 1998. Lehnert, Hendrik (ed.) . Pheochromocytoma; pathophysiology and clinical management. Basel: Karger; 2004. New, Maria . Advances in steroid disorders in children. Parma: Universita' Degli Studi di Parma; 2000. New, Maria I. (ed.) & Levine, Lenore S. (ed.) . Adrenal diseases in childhood. Basel: Karger; 1984. Vinson, G. P. (ed.) & Anderson, D. C. (ed.) . Adrenal glands, vascular system and hypertension. Bristol: Journal of Endocrinology; 1996. Aging: Brunner,D Jokl, E Eds. Physical activity and aging Basel: Karger,S; 1970. Corpas, Emiliano (ed.) . Endocrinology of Aging ; clinical aspects in diagrams and images. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2021. Morrison, Mary F. (ed.) . Hormones, gender and the aging brain ; the endocrine basis of geriatric psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. Olshansky, S. Jay & Carnes, Bruce A. The Quest for immortality ; science at the frontiers of aging. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 2001. Sinnott, Jan D. Sex roles and Aging : theory and research from a systems perspective. Basel: Karger; 1986. Werner Kohler, Jena (ed.) . Altern und lebenszeit ; vortrage anlablich der jahresversammlung vom 26. bis 29. ; marz 1999 zu halle (saale). Halle: Deutsche Akademie der Naurforscher Leopoldin; 1999. Auto-Immunity: Altman, Amnon (ed.) . Signal transducation pathways in autoimmunity. Basel: Karger; 2002. Bastenie, P. A. (ed.) & Gept, W. (ed.) & Addison, G. M. (ed.) . Immunity and autoimmunity in diabetes mellitus ; proceedings of the francqui foundation colloquium, ; brussels, april 30- may 1, 1973. -

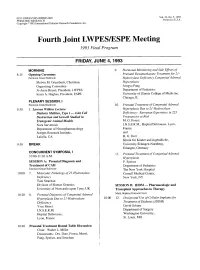

Fourth Joint LWPESJESPE Meeting 1993 Final Program

003 1-399819313305-0000$03.00/0 Vol. 33, No. 5, 1993 PEDIATRIC RESEARCH Printed in U.S.A. Copyright O 1993 International Pediatric Research Foundation, Inc. Fourth Joint LWPESJESPE Meeting 1993 Final Program FRIDAY, JUNE 4,1993 MORNING 9. Hormonal Monitoring and Side Effects of 8: 15 Opening ceremony Prenatal Dexamethasone Treatment for 21 - Fairmont Grand Ballroom Hydroxylase Deficiency Congenital Adrenal Melvin M. Grumbach, Chairman, Hyperplasia Organizing Committee SongyaPang Jo Anne Brasel, President, LWPES Department of Pediatrics Ieuan A. Hughes, President, ESPE University of Illinois College of Medicine, Chicago, IL PLENARY SESSION, I Fairmont Grand Ballroom 10. Prenatal Treatment of Congenital Adrenal 8:30 1. Lawson Wilkins Lecture: Hyperplasia Due to 21 -Hydroxylase Diabetes Mellitus, Type I - Islet Cell Deficiency: European Experience in 223 Destruction and Growth Studied in Pregnancies at Risk Transgenic Animal Models M. G. Forest Nora Sarvetnick I.N.S.E.R.M., Hopital Debrousse, Lyon, Department of Neuropharmacology France Scripps Research Institute, and LaJolla, CA H. G. Dorr Klinik fur Kinder and Jugendliche, 9:30 BREAK University Erlangen-Nurnberg, Erlangen, Germany CONCURRENT SYMPOSIA, I 11. Prenatal Treatment of Congenital Adrenal 10:OO-11:30 A.M. Hyperplasia SESSION A: Prenatal Diagnosis and P. Speiser Treatment of CAH Department of Pediatrics Fairmont Grand Ballroom The New York Hospital 10:OO 7. Molecular Pathology of 21 -Hydroxylase Cornell Medical Center, Deficiency New York, NY Tom Strachan Division of Human Genetics SESSION B: IDDM - Pharmacologic and University of Newcastle upon Tyne, UK Transplant Approaches to Therapy 10:20 8. Prenatal Diagnosis of Congenital Adrenal Mark Hopkins Peacock Court Hyperplasia Due to 21 -Hydroxylase 10:OO 12. -

Zum Download

100 Jahre Schweizerische Neurologische Gesellschaft 100 ans Société Suisse de Neurologie 100 anni Società Svizzera di Neurologia 1908–2008 Schwabe 100 Jahre Schweizerische Neurologische Gesellschaft 100 ans Société Suisse de Neurologie 100 anni Società Svizzera di Neurologia Herausgegeben von Claudio Bassetti und Marco Mumenthaler Schwabe Verlag Basel Sonderdruck aus Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie Vol. 159 n Nr. 4 n April 2008 anlässlich des 100-Jahr-Jubiläums der Schweizerischen Neurologischen Gesellschaft © 2008 by Schwabe AG, Verlag, Basel Lektorat: Christina Scherer Gesamtherstellung: Schwabe AG, Druckerei, Muttenz/Basel Printed in Switzerland ISBN 978-3-7965-2452-3 www.schwabe.ch Inhalt Schweizer Archiv für Neurologie und Psychiatrie Sommaire Archives suisses de neurologie et de psychiatrie Content Swiss Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry Editorial Editorial 142 n C. L. Bassetti, M. Mumenthaler SNG-Jubiläum Geschichte der Schweizerischen Neurologischen Gesellschaft im Kontext der nationalen 143 Jubilé SSN und internationalen Entwicklung der Neurologie SSN Jubilee n C. L. Bassetti, P. O. Valko History of neurological contributions in the Swiss Archives of Neurology and Psychiatry 157 n P. Valko, M. Mumenthaler, C. L. Bassetti 100 Jahre Neurologie Basel 171 n A. J. Steck, N. Loeliger, H.-R. Stöckli Geschichte der Neurologie in Bern 176 n C. W. Hess Historique du Service de Neurologie des Hôpitaux Universitaires de Genève 183 n T. Landis, P. R. Burkhard Parcours du service universitaire de neurologie de Lausanne entre 1954 et 2007 186 n F. Regli, P.-A. Despland Geschichte der Neurologischen Klinik und Poliklinik Zürich 191 n K. Hess Die neurologische Klinik des Kantonsspitals Aarau 198 n U. W. -

Prader–Willi Syndrome and Hypogonadism: a Review Article

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Prader–Willi Syndrome and Hypogonadism: A Review Article Cees Noordam 1,2,* , Charlotte Höybye 3,4 and Urs Eiholzer 1 1 Centre for Paediatric Endocrinology Zurich (PEZZ), 8006 Zurich, Switzerland; [email protected] 2 Department of Pediatrics, Radboud University Medical Centre, 6525 GA Nijmegen, The Netherlands 3 Department of Endocrinology, Karolinska University Hospital, 111 52 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Department of Molecular Medicine and Surgery, Karolinska Institute, 171 76 Stockholm, Sweden * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Prader-Labhart-Willi syndrome (PWS) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by intel- lectual disability, behavioural problems, hypothalamic dysfunction and specific dysmorphisms. Hypothalamic dysfunction causes dysregulation of energy balance and endocrine deficiencies, in- cluding hypogonadism. Although hypogonadism is prevalent in males and females with PWS, knowledge about this condition is limited. In this review, we outline the current knowledge on the clinical, biochemical, genetic and histological features of hypogonadism in PWS and its treatment. This was based on current literature and the proceedings and outcomes of the International PWS annual conference held in November 2019. We also present our expert opinion regarding the diag- nosis, treatment, care and counselling of children and adults with PWS-associated hypogonadism. Finally, we highlight additional areas of interest related to this topic and make recommendations for future studies. Keywords: Prader-Willi syndrome; hypogonadism; child; adult; review; diagnosis; treatment; substi- Citation: Noordam, C.; Höybye, C.; tution Eiholzer, U. Prader–Willi Syndrome and Hypogonadism: A Review Article. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 2705. https://doi.org/10.3390/ 1. -

Prof. Laron's Library of Pediatric Endocrinology (Print Copies at the Medical Library)

Prof. laron's library of pediatric endocrinology (print copies at the medical library) Adrenal: Fluck, C. E. (ed.) & Miler, W. L. (ed.) . Disorders of the human adrenal cortex. Basel: Karger; 2018. Krieger, D. T. Cushing's syndrome. Berlin: Springer; 1982. Lajic, Svetlana . Molecular analysis of mutated P450c21 in congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Stockholm: Department of Women and Child Health Pediatr; 1998. Lehnert, Hendrik (ed.) . Pheochromocytoma; pathophysiology and clinical management. Basel: Karger; 2004. Vinson, G. P. (ed.) & Anderson, D. C. (ed.) . Adrenal glands, vascular system and hypertension. Bristol: Journal of Endocrinology; 1996. Aging: Brunner,D Jokl, E Eds. Physical activity and aging Basel: Karger,S; 1970. Morrison, Mary F. (ed.) . Hormones, gender and the aging brain ; the endocrine basis of geriatric psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. Sinnott, Jan D. Sex roles and Aging : theory and research from a systems perspective. Basel: Karger; 1986. Werner Kohler, Jena (ed.) . Altern und lebenszeit ; vortrage anlablich der jahresversammlung vom 26. bis 29. ; marz 1999 zu halle (saale). Halle: Deutsche Akademie der Naurforscher Leopoldin; 1999. Autoimmunity: Altman, Amnon (ed.) . Signal transducation pathways in autoimmunity. Basel: Karger; 2002. Bastenie, P. A. (ed.) & Gept, W. (ed.) & Addison, G. M. (ed.) . Immunity and autoimmunity in diabetes mellitus ; proceedings of the francqui foundation colloquium, ; brussels, april 30- may 1, 1973. Amsterdam: Experta Medica; 1974. Pinchera, A. Et.al . Autoimmune aspects of endocrine disorders London: Academic Press; 1980. Schuurman, H.-J. & Feutren, G. & Bach, J. -F. Modern immunosuppressive. Basel: Birkhauser; 2001. Biochemistry: Bowman, Robert E. (ed.) & Datta, Surinder P. (ed.) . Biochemistry of brain and behavior New York: Plenum Press; 1970. Kleinkauf, Horst (ed.) & von Dohren, Hans (ed.) & Jaenicke, Lothar (ed.) . -

Intersex’ Children in Swiss Paediatric Medicine (1945–1970)

Medical History (2021), 65: 3, 286–305 doi:10.1017/mdh.2021.17 ARTICLE Doctors, families and the industry in the clinic: the management of ‘intersex’ children in Swiss paediatric medicine (1945–1970) Mirjam Janett1, Andrea Althaus1, Marion Hulverscheidt2, Rita Gobet3, Jürg Streuli4 and Flurin Condrau1* 1History of Medicine, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 2Modern History, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany 3Paediatric Urology, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 4Paediatric Palliative Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, Switzerland *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract This manuscript investigates clinical decisions and the management of ‘intersex’ children at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich between 1945 and 1970. This was an era of rapid change in paediatric medicine, something that was mirrored in Zurich. Andrea Prader, the principal figure in this paper, started his career during the late 1940s and was instrumental in moving the hospital towards focusing more on expertise in chronic diseases. Starting in 1950, he helped the Zurich hospital to become the premier centre for the treatment of so-called ‘intersex’ children. It is this treatment, and, in particular, the clinical decision-making that is the centre of our article. This field of medicine was itself not stable. Rapid development of diagnostic tools led to the emergence of new diagnostic categories, the availability of new drugs changed the management of the children’s bodies and an increased number of medical experts became involved in decision-making, a particular focus lay with the role of the children themselves and of course with their families. -

Doctors, Families and the Industry in the Clinic: the Management of ‘Intersex’ Children in Swiss Paediatric Medicine (1945–1970)

Medical History (2021), 65: 3, 286–305 doi:10.1017/mdh.2021.17 ARTICLE Doctors, families and the industry in the clinic: the management of ‘intersex’ children in Swiss paediatric medicine (1945–1970) Mirjam Janett1, Andrea Althaus1, Marion Hulverscheidt2, Rita Gobet3, Jürg Streuli4 and Flurin Condrau1* 1History of Medicine, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 2Modern History, University of Kassel, Kassel, Germany 3Paediatric Urology, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland 4Paediatric Palliative Medicine, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland, St. Gallen, Switzerland *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract This manuscript investigates clinical decisions and the management of ‘intersex’ children at the University Children’s Hospital Zurich between 1945 and 1970. This was an era of rapid change in paediatric medicine, something that was mirrored in Zurich. Andrea Prader, the principal figure in this paper, started his career during the late 1940s and was instrumental in moving the hospital towards focusing more on expertise in chronic diseases. Starting in 1950, he helped the Zurich hospital to become the premier centre for the treatment of so-called ‘intersex’ children. It is this treatment, and, in particular, the clinical decision-making that is the centre of our article. This field of medicine was itself not stable. Rapid development of diagnostic tools led to the emergence of new diagnostic categories, the availability of new drugs changed the management of the children’s bodies and an increased number of medical experts became involved in decision-making, a particular focus lay with the role of the children themselves and of course with their families. -

Belgian Journal of Paediatrics

B P Belgian Journal BELGISCHE VERENIGING of Paediatrics VOOR KINDERGENEESKUNDE J SOCIÉTÉ BELGE DE PÉDIATRIE Publication of the Belgian Society of Paediatrics 2020 - Volume 22 - number 4 - December Theme: Obesity Causes and consequences of childhood obesity Genetic forms of obesity Developmental exposure to Bisphenol A : a contributing factor to the increased incidence of obesity ? The interactions between obesity and sleep What about our vulnerable children in the multidisciplinary approach of childhood obesity or overweight? Prenatal, natal and postnatal determinants of childhood obesity A heavy question: how do we approach children with overweight or obesity in 2020? Interdisciplinary overweight outpatient management in pediatrics Inpatient treatment of children and adolescents with severe obesity Physical determinants of weight loss during a residential rehabilitation program for adolescents with obesity Bariatric surgery in adolescents: information for the general pediatrician Articles Recurrent acute event in an infant Progressive pneumonia with pleural effusion and pneumomediastinum as presenting symptom of a hypopharyngeal perforation in a one year old boy Survey about the alcohol consumption by minors in Flemish youth movements Management of arteriovenous malformations in pediatric population: about two cases A rare presentation of congenital spinal dermal sinus Some trainees are more equal than others - The paediatric residency payment gap, as illustrated in a cross-sectional study in Flanders Umbilical Venous Catheter-Related Complications: A Retrospective Study at the University Hospital of Leuven Made in Belgium Unravelling the genetic cause of life-threatening infections in children Paediatric Cochrane Corner Systemic treatments for eczema Belgische Vereniging voor Kindergeneeskunde Société Belge de Pédiatrie QUARTERLY V.U./E.R. S. C.