Cirencester: Town and Landscape

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLOUCESTERSHIRE. NOBT.B CIB.NEY, 61 Bennett Joseph, Farmer, Downhouse, R Holloway Pierce Hancock, Farmer, Smith Jn

• onu:o·roBY.] GLOUCESTERSHIRE. NOBT.B CIB.NEY, 61 Bennett Joseph, farmer, Downhouse, r Holloway Pierce Hancock, farmer, Smith Jn. draper & grocr. Low. Cam Upper Cam Lower Cam Thomas Sidney ( exors. of), coal mer Blick Robert, fruit merchant Hunt & Wintet'12otham Limited, wool· chants, Lower Cam Cam Conservative Association (Hrbt. !en cloth manufacturers, Cam mills Trotman Warren S. W. baker & corn, B. Thomas, sec) Ireland Joseph, Railway inn flour & offal merchant Cam Institute (Francis Mullins, sec.), Jenner Martin, farmer, Quarry Viney Albert E. assistant overseer, Lower Cam Lacey Felix & William, agric. imple- Helena house Champion Elizabeth (Miss), shop- ment agents, Upthrnp iron works Viney Thomas, coal & salt merchant, keeper, Upper Cam Lacey John, photographer, Low. Cam Helena house, Coaley junction ; &. Cornock John, Prince of Wales P.H. Lea Elizabeth (Mrs.), farmer, Dray- at Dursley railway station Berkeley road (letters via Berkeley) cott farm Webber Elizabeth (Mrs.), shopkeeper Daniels T. H. & J. Limited, leather Liberal Association (branch) (Gordon Weeks Harry Wakeham, boot maker, board manufacturers Malpruss, sec) Lower Cam Edwards Nellie (Miss), poultry Mabbett Daniel & Son, mill peck Weight Thos. farmer, Upthrup farm farmer, Water end manufacturers & dressers,Low.Cam Welcome Coffee Tavern & Reading Ford Absalom, blacksmith, Low. Cam l\falpass Charles, mason, Quarry Room (Mrs. C. E. Stone, mangrss) Gabb George & Thomas, butchers, Malpass Pierce, farmer, Beyon house, White Hartley, miller (water), Hal Lower Cam Lower Cam more mills Gabb Francis, painter, Sand pits Manning Fanny (:\Iiss), shopkeeper Whitmore Waiter, grocr. Low. Cam Garn Fredk. Wm. farmer,Upper Cam Pain FrPAl.erick John, farmer, Wood- Wiggall Douglas Frederick, baker, & Gazard Lawford, farmer, Lower Cam end green post office, Lower Cam Gazard Thomas, farmer, Knapp farm, Pain William, farmer, Clingre farm Willdns Edwin,farmer,WalnutTree fm Lower Cam Parslow Stepben, market gardener, Williams James, fa.rmer, Woodlield Griffiths Chas. -

Sheepscote Lower End, Daglingworth, Gloucestershire Sheepscote

SHEEPSCOTE LOWER END, DAGLINGWORTH, GLOUCESTERSHIRE SHEEPSCOTE LOWER END • DAGLINGWORTH GLOUCESTERSHIRE A well-presented detached modern family house, quietly tucked away along a no-through road on the edge of a popular Cotswold village close to Cirencester Hall • Cloakroom • Sitting room • Dining room • Family room/ Bedroom 5 • Conservatory • Kitchen/Breakfast room with AGA • Utility/Boot room Master suite of double bedroom, dressing room and bathroom Three further bedrooms • Family bathroom Garage/Workshop • Parking • Garden store • Gardens In all about 0.25 acres Cirencester 3 miles • Kemble Station 6 miles (Paddington 80 minutes) • M5 (J11A) 10 miles Cheltenham 12 miles • Swindon 16 miles • M4 (J15) 18 miles (All distances and times are approximate) These particulars are intended only as a guide and must not be relied upon as statements of fact. Your attention is drawn to the Important Notice on the last page of the text. Situation • Sheepscote is situated in Lower End, a small no-through lane on the southern edge of Daglingworth.Daglingworth is a quiet and unspoilt Cotswold village on the edge of the Duntisbourne Valley. The village has a Church and Village Hall, the nearest Primary School, shop and Post Office are just two miles away in Stratton. • The attractive market town of Cirencester is about 3 miles away. It has a comprehensive range of shops as well as excellent schooling, healthcare and professional services. • The property is well placed for communications with the large commercial centres of Swindon and the regency town of Cheltenham being within easy travelling distance, via the A419/417 dual carriageway. It also provides quick access to both the M4 and M5 motorways. -

Review of the Year 2017-18

REVIEW OF THE YEAR 2017-18 The Annual Report of Cotswold District Council COTSWOLD DISTRICT COUNCIL Welcome to Cotswold District Council’s Review of the Year for 2017-18 We have had yet another good year in 2017/18, addressing a wide range of top tasks and also achieving planned savings of over £200,000. Our success stems in part from our partnership (within the Publica Group) - with three other councils - West Oxfordshire, Forest of Dean and Cheltenham. Through working within this partnership, we managed to freeze our portion of the Council Tax bill for 2017/18 at a time when the vast majority of authorities increased costs. Previously we froze our share in 2016/17, reduced it by 5% in 2015/16, reduced it by 3% in 2014/15 and by 5% in 2013/14 . The freeze for 2017/18 meant that the actual amount being charged was lower than the figure ten years ago. In other words, the typical payment for a resident in a Band D property would have seen a real terms cut of 25% over the last six years. We have also frozen charges for car parking and garden waste collections. We can also report further progress on several flood alleviation projects in the Cotswold district. Additionally, we delivered 247 affordable homes during 2017/18, comfortably ahead of our goal of delivering a minimum of 150 homes. Thanks to the efforts of our residents we continue to achieve the highest levels of recycling in Gloucestershire (almost 60%% of all household waste is recycled, reused or composted). -

University Gate CIRENCESTER

University Gate CIRENCESTER 22 acres (8.9 ha) of prime commercial development land with outline permission INTRODUCTION University Gate, Cirencester, offers a unique opportunity in the form of 22 acres of development land, with a prominent road frontage at the western entrance to Cirencester. This popular and expanding market town, with a population of approximately 20,000, is unofficially known as the ‘Capital of The Cotswolds’. Loveday, as agents to the Royal Agricultural University, are instructed to seek expressions of interest in this development land. CHESTERTON MARKET PLACE A419 CIRENCESTER DEVELOPMENT LAND OFFICE PARK (2,350 NEW HOMES) CHURCH CIRENCESTER UNIVERSITY GATE A429 TO TETBURY A419 TO STROUD LOCATION Cirencester is situated in the Cotswolds, an area of outstanding natural beauty in the South West of England. The town benefits Birmingham from direct access to the A417 / A419 dual carriageway which offers easy access to junction 11a of the M5 to the north west M1 and Junction 15 of the M4 motorway to the south east. M5 M40 Cheltenham Gloucester Luton A419 A417 Oxford Gloucester Cirencester M5 J11a Cardiff A417 Gloucester Rd Swindon M4 M4 Burford Road Chippenham Reading Bristol Bath M3 Salisbury Leisure Centre TOWN CENTRE St. James's Place The main conurbations of Cheltenham, Gloucester and Swindon Waitrose Swindon Road Swindon M4 J15 A419 are 18, 15 and 19 miles away respectively. Kemble Railway Stroud Road Station, which offers a direct rail link to London Paddington, is just 3 miles distant. University University Gate is situated at the western entrance to Cirencester, Gate at the junction of the busy A419 Stroud Road and A429 Tetbury Road. -

Gi200900.Pdf

Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 2009 Contents Editorial......................................................................................................................................2 From Willow to Wicket: A Lost Cricket Bat Willow Plantation in Leonard Stanley. By Stephen Mills ......................................................................... 3-8 Matthews & Company – Gloucester’s Premier Furniture Manufacturers By Hugh Conway-Jones ......................................................................................... 9-13 Two Recently Discovered Field Books from Sopwith’s Mineral Survey of the Forest of Dean. By Ian Standing ......................................................................... 14-22 The Canal Round House at Inglesham Lock By John Copping (Adapted for the GSIA Journal by Alan Strickland) ..................................................................... 23-35 Upper Redbrook Iron Works 1798-9: David Tanner's Bankruptcy By Pat Morris ...... 36-40 The Malthouse, Tanhouse Farm, Church End, Frampton on Severn, Gloucestershire By Amber Patrick ................................................................................................. 41-46 The Restoration of the Cotswold Canals, July 2010 Update. By Theo Stening .............. 47-50 GSIA Visit Reports for 2009 ............................................................................................. 51-57 Book Reviews ................................................................................................................... -

GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the Database of the Milestone Society

Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. Parish Location Position GL_AVBF05 SP 102 149 UC road (was A40) HAMPNETT West Northleach / Fosse intersection on the verge against wall GL_AVBF08 SP 1457 1409 A40 FARMINGTON New Barn Farm by the road GL_AVBF11 SP 2055 1207 A40 BARRINGTON Barrington turn by the road GL_AVGL01 SP 02971 19802 A436 ANDOVERSFORD E of Andoversford by Whittington turn (assume GL_SWCM07) GL_AVGL02 SP 007 187 A436 DOWDESWELL Kilkenny by the road GL_BAFY07 ST 6731 7100 A4175 OLDLAND West Street, Oldland Common on the verge almost opposite St Annes Drive GL_BAFY07SL ST 6732 7128 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, left hand side GL_BAFY07SR ST 6733 7127 A4175 OLDLAND Oldland Common jct High St/West Street on top of wall, right hand side GL_BAFY08 ST 6790 7237 A4175 OLDLAND Bath Road, N Common; 50m S Southway Drive on wide verge GL_BAFY09 ST 6815 7384 UC road SISTON Siston Lane, Webbs Heath just South Mangotsfield turn on verge GL_BAFY10 ST 6690 7460 UC road SISTON Carsons Road; 90m N jcn Siston Hill on the verge GL_BAFY11 ST 6643 7593 UC road KINGSWOOD Rodway Hill jct Morley Avenue against wall GL_BAGL15 ST 79334 86674 A46 HAWKESBURY N of A433 jct by the road GL_BAGL18 ST 81277 90989 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON near Leighterton on grass bank above road GL_BAGL18a ST 80406 89691 A46 DIDMARTON Saddlewood Manor turn by the road GL_BAGL19 ST 823 922 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON N of Boxwell turn by the road GL_BAGL20 ST 8285 9371 A46 BOXWELL WITH LEIGHTERTON by Lasborough turn on grass verge GL_BAGL23 ST 845 974 A46 HORSLEY Tiltups End by the road GL_BAGL25 ST 8481 9996 A46 NAILSWORTH Whitecroft by former garage (maybe uprooted) GL_BAGL26a SO 848 026 UC road RODBOROUGH Rodborough Manor by the road Registered Charity No 1105688 1 Entries in red - require a photograph GLOUCESTERSHIRE Extracted from the database of the Milestone Society National ID Grid Reference Road No. -

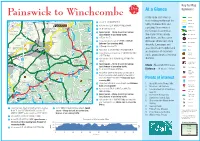

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Journal Issue 3, May 2013

Stonehouse History Group Journal Issue 3 May 2013 ISSN 2050-0858 Published by Stonehouse History Group www.stonehousehistorygroup.org.uk [email protected] May 2013 ©Stonehouse History Group Front cover sketch “The Spa Inn c.1930” ©Darrell Webb. We have made every effort to obtain permission from the copyright owners to reproduce their photographs in this journal. Modern photographs are copyright Stonehouse History Group unless otherwise stated. No copies may be made of any photographs in this issue without the permission of Stonehouse History Group (SHG). Editorial Team Vicki Walker - Co-ordinating editor Jim Dickson - Production editor Shirley Dicker Janet Hudson John Peters Darrell Webb Why not become a member of our group? We aim to promote interest in the local history of Stonehouse. We research and store information about all aspects of the town’s history and have a large collection of photographs old and new. We make this available to the public via our website and through our regular meetings. We provide a programme of talks and events on a wide range of historical topics. We hold meetings on the second Wednesday of each month, usually in the Town Hall at 7:30pm. £1 members; £2 visitors; annual membership £5 2 Stonehouse History Group Journal Issue 3, May 2013 Contents Obituary of Les Pugh 4 Welcome to our third issue 5 Oldends: what’s in an ‘s’? by Janet Hudson 6 Spa Inn, Oldends Lane by Janet Hudson, Vicki Walker and Shirley Dicker 12 Oldends Hall by Janet Hudson 14 Stonehouse place names by Darrell Webb 20 Charles -

A Modern History of Britain's Roman Mosaic Pavements

Spectacle and Display: A Modern History of Britain’s Roman Mosaic Pavements Michael Dawson Archaeopress Roman Archaeology 79 Archaeopress Publishing Ltd Summertown Pavilion 18-24 Middle Way Summertown Oxford OX2 7LG www.archaeopress.com ISBN 978-1-78969-831-2 ISBN 978-1-78969-832-9 (e-Pdf) © Michael Dawson and Archaeopress 2021 Front cover image: Mosaic art or craft? Reading Museum, wall hung mosaic floor from House 1, Insula XIV, Silchester, juxtaposed with pottery by the Aldermaston potter Alan Gaiger-Smith. Back cover image: Mosaic as spectacle. Verulamium Museum, 2007. The triclinium pavement, wall mounted and studio lit for effect, Insula II, Building 1 in Verulamium 2007. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owners. This book is available direct from Archaeopress or from our website www.archaeopress.com Contents List of figures.................................................................................................................................................iii Preface ............................................................................................................................................................v 1 Mosaics Make a Site ..................................................................................................................................1 Introduction ..............................................................................................................................................1 -

Try the Wine: Food As an Expression of Cultural Identity in Roman Britain

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 8-2020 Try the Wine: Food as an Expression of Cultural Identity in Roman Britain Molly Reininger Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Reininger, Molly, "Try the Wine: Food as an Expression of Cultural Identity in Roman Britain" (2020). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7867. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7867 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRY THE WINE: FOOD AS AN EXPRESSION OF CULTURAL IDENTITY IN ROMAN BRITAIN by Molly Reininger A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF THE ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ______________________ Frances Titchener, Ph.D . Seth Archer, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ______________________ Susan Cogan, Ph.D. Gabriele Ciciurkaite, Ph.D. Committee Member Outside Committee Member ______________________ Janis L. Boettinger, Ph.D. Acting Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2020 ii Copyright © Molly Reininger 2020 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Try the Wine: Food as an Expression of Cultural Identity in Roman Britain by Molly Reininger, Master of the Arts Utah State University, 2020 Major Professor: Dr. Frances Titchener Department: History This thesis explores the relationship between goods imported from Rome to Britannia, starting from the British Iron Age to the Late Antique period, and how their presence in the province affected how those living within viewed their cultural identity. -

The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 2 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-2-2 The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great Stanislav Doležal (University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice) Abstract The article argues that Constantine the Great, until he was recognized by Galerius, the senior ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Emperor of the Tetrarchy, was an usurper with no right to the imperial power, nothwithstand- ing his claim that his father, the Emperor Constantius I, conferred upon him the imperial title before he died. Tetrarchic principles, envisaged by Diocletian, were specifically put in place to supersede and override blood kinship. Constantine’s accession to power started as a military coup in which a military unit composed of barbarian soldiers seems to have played an impor- tant role. Keywords Constantine the Great; Roman emperor; usurpation; tetrarchy 19 Stanislav Doležal The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great On 25 July 306 at York, the Roman Emperor Constantius I died peacefully in his bed. On the same day, a new Emperor was made – his eldest son Constantine who had been present at his father’s deathbed. What exactly happened on that day? Britain, a remote province (actually several provinces)1 on the edge of the Roman Empire, had a tendency to defect from the central government. It produced several usurpers in the past.2 Was Constantine one of them? What gave him the right to be an Emperor in the first place? It can be argued that the political system that was still valid in 306, today known as the Tetrarchy, made any such seizure of power illegal. -

Gerald Dyson

CONTEXTS FOR PASTORAL CARE: ANGLO-SAXON PRIESTS AND PRIESTLY BOOKS, C. 900–1100 Gerald P. Dyson PhD University of York History March 2016 3 Abstract This thesis is an examination and analysis of the books needed by and available to Anglo-Saxon priests for the provision of pastoral care in the tenth and eleventh centuries. Anglo-Saxon priests are a group that has not previously been studied as such due to the scattered and difficult nature of the evidence. By synthesizing previous scholarly work on the secular clergy, pastoral care, and priests’ books, this thesis aims to demonstrate how priestly manuscripts can be used to inform our understanding of the practice of pastoral care in Anglo-Saxon England. In the first section of this thesis (Chapters 2–4), I will discuss the context of priestly ministry in England in the tenth and eleventh centuries before arguing that the availability of a certain set of pastoral texts prescribed for priests by early medieval bishops was vital to the provision of pastoral care. Additionally, I assert that Anglo- Saxon priests in general had access to the necessary books through means such as episcopal provision and aristocratic patronage and were sufficiently literate to use these texts. The second section (Chapters 5–7) is divided according to different types of priestly texts and through both documentary evidence and case studies of specific manuscripts, I contend that the analysis of individual priests’ books clarifies our view of pastoral provision and that these books are under-utilized resources in scholars’ attempts to better understand contemporary pastoral care.