Journal Issue 3, May 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, a Descriptive Account of Each Place

Hunt & Co.’s Directory March 1849 - Transcription of the entry for Dursley, Gloucestershire Hunt & Co.’s Directory for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 Transcription of the entry for Dursley and Berkeley, Gloucestershire Background The title page of Hunt & Co.’s Directory & Topography for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 declares: HUNT & CO.'S DIRECTORY & TOPOGRAPHY FOR THE CITIES OF GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, AND THE TOWNS OF BERKELEY, CIRENCESTER, COLEFORD, DURSLEY, LYDNEY, MINCHINHAMPTON, MITCHEL-DEAN, NEWENT, NEWNHAM, PAINSWICK, SODBURY, STROUD, TETBURY, THORNBURY, WICKWAR, WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE, &c. W1TH ABERAVON, ABERDARE, BRIDGEND, CAERLEON, CARDIFF, CHEPSTOW, COWBRIDCE, LLANTRISSAINT, MERTHYR, NEATH, NEWBRIDGE, NEWPORT, PORTHCAWL, PORT-TALBOT, RHYMNEY, TAIBACH, SWANSEA, &c. CONTAINING THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF The Nobility, Gentry, Clergy, PROFESSIONAL GENTLEMEN, TRADERS, &c. RESlDENT THEREIN. A Descriptive Account of each Place, POST-OFFICE INFORMATION, Copious Lists of the Public Buildings, Law and Public Officers - Particulars of Railroads, Coaches, Carriers, and Water Conveyances - Distance Tables, and other Useful Information. __________________________________________ MARCH 1849. ___________________________________________ Hunt & Co. produced several trade directories in the mid 1850s although the company was not prolific like Pigot and Kelly. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley, which also covered Cambridge, Uley and Newport, gave a comprehensive listing of the many trades people in the area together with a good gazetteer of what the town was like at that time. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley is found on pages 105-116. This transcription was carried out by Andrew Barton of Dursley in 2005. All punctuation and spelling of the original is retained. In addition the basic layout of the original work has been kept, although page breaks are likely to have fallen in different places. -

St Matthews Court, Cainscross, Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 4LH Price £85,000 (Leasehold) St Matthews Court, Cainscross, Stroud, GL5 4LH

St Matthews Court, Cainscross, Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 4LH Price £85,000 (Leasehold) St Matthews Court, Cainscross, Stroud, GL5 4LH A well presented TWO bedroom first floor duplex retirement apartment within this purpose built complex. Modern fitted kitchen and shower suite. Stair lift to main bedroom. The first floor apartments are conveniently accessed via a lift. Outside can be found the landscaped communal courtyard gardens. Sawyers Estate Agents are delighted to offer to the market INNER HALL SELLING AGENT chain free this two bedroom first floor duplex retirement Coving, doors to: Sawyers Estate Agents apartment (over two floors) within this purpose built 17 George Street complex situated off Church Road in Cainscross. SITTING ROOM/BEDROOM TWO 4.45m (14'7'') x 2.82m Stroud (9'3'') Gloucestershire The first floor apartments are conveniently accessed via a Double glazed window to rear, coving, built in airing cupboard GL5 3DP lift. The accommodation in brief comprises: Private housing water tank, television point and electric storage heater. entrance, entrance hall, dining room, kitchen, living 01453 751647 room/bedroom two, bathroom with a further bedroom of SHOWER ROOM [email protected] the first floor. Suite comprising shower cubicle with `Mira Sport` shower, low www.sawyersestateagents.co.uk level W/C, wash hand basin set within vanity unit with roll edge Outside can be found the landscaped communal courtyard tops, wall mounted mirror unit with shaver point and spotlight, Local Authority garden and allocated parking. Benefits include a `Lifeline` part tiled walls, electric heated towel rail, `lifeline` emergency Stroud District Council - Band B call system with emergency switches in most roms. -

Stroud District Local Plan Review Draft Local Plan Consultation

Stroud District Local Plan Review: Draft Local Plan Consultation The Berkeley Estate Stroud District Local Plan Review Draft Local Plan Consultation Representations prepared by Savills on behalf of ‘The Trustees of the Berkeley Settlement’ (The Berkeley Estate) savills.co.uk January 2020 1 Stroud District Local Plan Review: Draft Local Plan Consultation Introduction 1. These representations have been prepared by Savills on behalf of The Berkeley Estate (TBE) in response to the consultation on the Draft Stroud District Local Plan (Draft LP) which ends on 22 January 2020. 2. The Berkeley family, who remain integral to TBE, has been associated with Berkeley since the 12th Century. The family’s long term commitment to the area, its community and the rural economy means that the use/development of its land is important to its legacy. For the same reason, TBE also engages with the development of the wider District, and takes an active interest in the Development Plan process. 3. TBE land interest is focused in the south western part of the District, extending to approximately 6,000 acres in Gloucestershire’s Berkeley Vale. It includes a mediaeval Deer Park, a number of farms let to farming tenants (where the families have often been on the land for generations), cottages, offices, a hotel and two pubs. TBE also owns the New Grounds at Slimbridge, where the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust is based, and about five miles of the bed of the River Severn. It is a vibrant business providing employment and business opportunities. 4. Specific comments within these representations are made in respect of the proposed allocations relating to the ‘land at Focus School, Wanswell’, ‘Sharpness Garden Village’ and ‘Wisloe Garden Village’. -

KINGSWOOD Village Design Statement Supplementary Information

KINGSWOOD Village Design Statement Supplementary Information 1 Contents Appendix 1 Community Assets and Facilities Appendix 2 Table of Organisations and Facilities within Kingswood Appendix 3 Fatal and Serious Accidents Kingswood Appendix 4 Fatal and serious Accidents Kingswood and Wotton-under-Edge Appendix 5 Wotton Road Charfield, August 2013 Appendix 6 Hillesley Road, Kingswood,Traffic Survey, September 2012 Appendix 7 Wickwar Road Traffic Survey Appendix 8 Kingswood Parish Council Parish Plan 2010 Appendix 9 List of Footpaths Appendix 10 Agricultural Land Classification Report June 2014 Appendix 11 Kingswood Playing Field Interpretation Report on Ground Investigation Appendix 12 Peer Review of Flood Risk Assessment Appendix 13 Kingswood Natural Environment Character Assessment Appendix 14 Village Design Statement Key Dates 2 Appendix 1 Community Assets and Facilities 3 Community Assets and Facilities Asset Use Location Ownership St Mary’s Church Worship High Street Church and Churchyard Closed Churchyard maintained by Kingswood parish Council The St Mary’s Room Community High Street Church Congregational Chapel Worship Congregational Chapel Kingswood Primary School Education Abbey Street Local Education Authority Lower School Room Education/ Worship Chapel Abbey Gateway Heritage Abbey Street English Heritage Dinneywicks Pub Recreation The Chipping Brewery B&F Gym and Coffee shop Sport and Recreation The Chipping Limited Company Spar Shop/Post Office Retail The Chipping Hairdressers Retail Wickwar Road All Types Roofing Retail High -

COTSWOLD CANALS a GUIDE for USERS Eastington to Thrupp

STROUD VALLEYS CANAL COMPANY COTSWOLD CANALS A GUIDE FOR USERS Eastington to Thrupp Bowbridge Lock ISSUE DECEMBER 06 2019 www.stroudvalleyscanal.co.uk 2 KEY TO SYMBOLS NAVIGATION Road Railway Station HAZARDS Path (may not be Bus Stop CANAL LINE suitable for (selected) wheelchairs) Part navigable - Disability Route - Taxi Rank or office canoes etc see SVCC website Fully Navigable Railway Bridge Car Park - Navigable Infilled Railway Bridge Fuel Brown line - Not navigable shows towpath Toilets SLIP-WAY MOORINGS Toilets Disabled WINDING HOLE/ V Visitor TURNING POINT P Permanent / Showers Long Term LOCKS Launderette Lock - Navigable with FACILITIES landing stage or space Water Point Post Office Lock - Not navigable Refuse Disposal BANK Bank BRIDGES £ Modern V C Cotswold Canals Trust Cash Machine Visitor Centre Heritage Shop Heritage - Restored Cotswold Canals Trust Work Depot but not navigable Cinema FOOT Footbridge Pub E Lift - Electric Minor Injuries Unit LIFT with landing stages See p 11 Food Outlet E Lift - Electric FIXED LIFT Defibrillator Coffee Shop M Swing - Manual SWING with landing stages E Swing - Electric Vet - see p 11 SWING Hotel with landing stages INTRODUCTION 3 This guide covers a seven mile section of the Cotswold Canals. They comprise the Stroudwater Navigation to the west of Stroud and the Thames & Severn Canal to the east. In these pages you will find lots of information to help you enjoy the waterway in whatever way you choose. Much of the content will be especially helpful to boaters with essential instructions for navigation. The Cotswold Canals extend way beyond this section as you can see on the map to the right. -

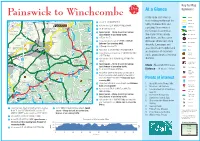

Painswick to Winchcombe Cycle Route

Great Comberton A4184 Elmley Castle B4035 Netherton B4632 B4081 Hinton on the Green Kersoe A38 CHIPPING CAMPDEN A46(T) Aston Somerville Uckinghall Broadway Ashton under Hill Kemerton A438 (T) M50 B4081 Wormington B4479 Laverton B4080 Beckford Blockley Ashchurch B4078 for Tewkesbury Bushley B4079 Great Washbourne Stanton A38 A38 Key to Map A417 TEWKESBURY A438 Alderton Snowshill Day A438 Bourton-on-the-Hill Symbols: B4079 A44 At a Glance M5 Teddington B4632 4 Stanway M50 B4208 Dymock Painswick to WinchcombeA424 Linkend Oxenton Didbrook A435 PH A hilly route from start to A Road Dixton Gretton Cutsdean Hailes B Road Kempley Deerhurst PH finish taking you through the Corse Ford 6 At fork TL SP BRIMPSFIELD. B4213 B4211 B4213 PH Gotherington Minor Road Tredington WINCHCOMBE Farmcote rolling Cotswold hills and Tirley PH 7 At T junctionB4077 TL SP BIRDLIP/CHELTENHAM. Botloe’s Green Apperley 6 7 8 9 10 Condicote Motorway Bishop’s Cleeve PH Several capturing the essence of Temple8 GuitingTR SP CIRENCESTER. Hardwicke 22 Lower Apperley Built-up Area Upleadon Haseld Coombe Hill the Cotswold countryside. Kineton9 Speed aware – Steep descent on narrow B4221 River Severn Orchard Nook PH Roundabouts A417 Gorsley A417 21 lane. Beware of oncoming traffic. The route follows mainly Newent A436 Kilcot A4091 Southam Barton Hartpury Ashleworth Boddington 10 At T junction TL. Lower Swell quiet lanes, and has some Railway Stations B4224 PH Guiting Power PH Charlton Abbots PH11 Cross over A 435 road SP UPPER COBERLEY. strenuous climbs and steep B4216 Prestbury Railway Lines Highleadon Extreme Care crossing A435. Aston Crews Staverton Hawling PH Upper Slaughter descents. -

Norborne Berkeley's Politics.Indd 197 25/01/2012 09:55 198 William Evans

Trans. Bristol & Gloucestershire Archaeological Society 129 (2011), 197–219 Norborne Berkeley’s Politics: Principle, Party or Pragmatism? By WILLIAM EVANS Introduction This paper examines an aspect of the political career of Norborne Berkeley, baron Botetourt, who lived 1717–1770. A south Gloucestershire landowner, mine owner and tory, he was elected MP for Gloucestershire in 1741 with support from the jacobite Beauforts, into whose family his sister married.1 Whatever may have been the terms of that support, Berkeley distanced himself from their jacobitism and, though remaining a tory (and therefore at first proscribed from office), he became a loyal supporter of the Hanoverians, generally aligning himself with, but not overtly joining, political groupings as inclination and principle suggested. After the broad-bottom administration relaxed the prohibitions against tories holding official posts, Berkeley achieved some, but never high, political office – a proposal that he be appointed secretary at war was blocked – but under Bute he obtained a place at the court of George III, and successfully claimed a dormant peerage. Fortuitously he moved the fateful resolution that precipitated the American revolution. When he encountered financial difficulties through investment in a manufacturing company, he was helped by appointment as governor of Virginia, where his loyalty to the king conflicted with his personal sympathy with the colonists. Most historians have ignored Berkeley. Those that have noticed him tend to disregard or dismiss his political -

16A Quedgeley - Haresfield - Standish - Stonehouse - Cainscross Road

16A Quedgeley - Haresfield - Standish - Stonehouse - Cainscross Road Ebley Coaches Timetable valid from 01/05/2018 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch Hardwicke, just before One Stop Shop 0743 Quedgeley, o/s Telephone Exchange 0745 Haresfield, in School Entrance 0750 § Little Haresfield, by Haresfield Turn 0757 Standish, opp Court Farms 0800 § Standish, by The Shieling 0800 § Stroud Green, before Oxlynch Lane 0800 § Stroud Green, opp The Old Barn 0800 § Stonehouse, by Crowcumepill 0801 Stonehouse, corner of Horsemarling Lane 0802 § Stonehouse, nr Grosvenor Road 0802 Stonehouse, by The Nippy Chippy 0805 § Stonehouse, o/s Medical Centre 0807 Stonehouse, opp Elgin Mall 0810 § Stonehouse, corner of Pearcroft Road 0811 § Cainscross, before Marling School 0823 Stroud, Marling and Stroud High Schools (Stop 3) 0825 Saturdays Sundays no service no service Service Restrictions: Sch - Gloucestershire School Days Notes: § - Time at this stop is indicative. You are advised to be at any stop several minutes before the times shown 16A Cainscross Road - Stonehouse - Standish - Haresfield - Quedgeley Ebley Coaches Timetable valid from 01/05/2018 until further notice. Direction of stops: where shown (eg: W-bound) this is the compass direction towards which the bus is pointing when it stops Mondays to Fridays Service Restrictions Sch Stroud, Marling and Stroud High Schools (Stop 2) 1545 § Dudbridge, after -

Local Insight Profile for 'Berkeley CP' Area Gloucestershire Parish Profiles

1 Local Insight profile for ‘Berkeley CP’ area Gloucestershire Parish Profiles Report created 9 November 2016 Finding your way around this Local Insight profile 2 Introduction Page 3 for an introduction to this report 25% of people have no qualifications in Berkeley CP compared There are 1,880 people living in Berkeley CP with 22% across England See pages 4-9 for more information on population by age and gender, ethnicity, country See pages 35-37 for more information on qualifications, pupil attainment and early years of birth, language, migration, household composition and religion Population Education & skills educational progress 7% of children are living in poverty in Berkeley CP compared 46% people aged 16-74 are in full-time employment in Berkeley with 19% across England CP compared with 39% across England See pages 10-21 for more information on children in poverty, people out of work, people See pages 38-42 for more information on people’s jobs, job opportunities, income and local Vulnerable groups in deprived areas, disability, pensioners and other vulnerable groups Economy businesses 2% of households lack central heating in Berkeley CP compared with 3% across England 17% of households have no car in Berkeley CP compared with 26% across England See pages 22-28 for more information on housing characteristics: dwelling types, Access & transport Housing housing tenure, affordability, overcrowding, age of dwelling and communal See pages 43-45 for more information on transport, distances services and digital services establishments -

The Fleece Medical Society

Bristol Medico-Chirurgical Journal January/April 1983 The Fleece Medical Society H. J. Eastes, M.B., B.S., F.R.C.G.P. General Practitioner, Marshfield The Bristol Medico-Chirurgical Society was formed in 1874 and 9 years later a hundred years ago its journal first appeared. However, some 84 years ear- lier, on 21st May 1788, five members of our pro- fession all school friends or fellow students met in the parlour of the Fleece Inn at Rodborough, in the valley between Stroud and Nailsworth and resolved to set up the Gloucestershire Medical Society, better known as the Fleece Medical Society. The Fleece Inn, built in 1753, was patronised by members of the woollen trade which flourished in the valley. In 1853 the licence seems to have been transferred to a building nearer Stroud and known as the Old Fleece Inn. The original building in which Jenner and his friends met is now a private residence Hillgrove House on the A46 (Figure 1). Two of the five members founding the Fleece Medical Society, Edward Jenner of Berkeley and John Hickes of Gloucester, were already members of the Convivio-Medical Society meeting at the Ship Inn at Alveston near Bristol, a largely social club whose members were threatening to expel Jenner for his insistence on the importance of Coxpox as a protection against Smallpox. This may have been the spur that brought these five friends together to form what was, I believe, the oldest provincial medical society of which records still exist. The minutes are preserved, thanks to Sir William Osier The original Fleece Inn who bought them from Dr. -

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday

7-Night Cotswolds Guided Walking Holiday Tour Style: Guided Walking Destinations: Cotswolds & England Trip code: BNBOB-7 1 & 2 HOLIDAY OVERVIEW Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking. On our Guided Walking holidays you'll discover glorious golden stone villages with thatched cottages, mansion houses, pastoral countryside and quiet country lanes. WHAT'S INCLUDED • High quality en-suite accommodation in our country house • Full board from dinner upon arrival to breakfast on departure day • 5 days guided walking and 1 free day • Use of our comprehensive Discovery Point • Choice of up to three guided walks each walking day • The services of HF Holidays Walking Leaders www.hfholidays.co.uk PAGE 1 [email protected] Tel: +44(0) 20 3974 8865 HOLIDAYS HIGHLIGHTS • Explore the beautiful countryside and rich history of the Cotswolds • Gentle hills, picture-postcard villages and tempting tea shops make this quintessentially English countryside perfect for walking • Let your leader bring the picturesque countryside and history of the Cotswolds to life • In the evenings relax and enjoy the period features and historic interest of Harrington House ITINERARY Version 1 Day 1: Arrival Day You're welcome to check in from 4pm onwards. Enjoy a complimentary Afternoon Tea on arrival. Day 2: South Along The Windrush Valley Option 1 - The Quarry Lakes And Salmonsbury Camp Distance: 6½ miles (10.5km) Ascent: 400 feet (120m) In Summary: A circular walk starts out along the Monarch’s Way reaching the village of Clapton-on-the-Hill. We return along the Windrush valley back to Bourton. -

Pathology Van Route Information

Cotswold Early Location Location Depart Comments Start CGH 1000 Depart 1030 Depart 1040 if not (1005) going to Witney Windrush Health Centre Witney 1100 Lechlade Surgery 1125 Hilary Cottage Surgery, Fairford 1137 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1205 Moore Health Centre BOW 1218 George Moore Clinic BOW 1223 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1237 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1247 White House Surgery MIM 1252 Mann Cottage MIM 1255 Chipping Campden Surgery 1315 Barn Close MP Broadway 1330 Arrive CGH 1405 Finish 1415 Cotswold Late Location Location Depart Comments Start Time 1345 Depart CGH 1400 Abbey Medical Practice Evesham 1440 Merstow Green 1445 Riverside Surgery 1455 CGH 1530-1540 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1620 Moore Health Centre BOW 1635 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1655 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1705 White House Surgery M-in-M 1710 Mann Cottage MIM 1715 Chipping Campden Surgery 1735 Barn Close MP Broadway 1750 Winchcombe MP 1805 Cleeve Hill Nursing Home Winchcombe 1815 Arrive CGH 1830 Finish 1845 CONTROLLED DOCUMENT PHOTOCOPYING PROHIBITED Visor Route Information- GS DR 2016 Version: 3.30 Issued: 20th February 2019 Cirencester Early Location Location Depart Comments Start 1015 CGH – Pathology Reception 1030 Cirencester Hospital 1100-1115 Collect post & sort for GPs Tetbury Hospital 1145 Tetbury Surgery (Romney House) 1155 Cirencester Hospital 1220 Phoenix Surgery 1230 1,The Avenue, Cirencester 1240 1,St Peter's Rd., Cirencester 1250 The Park Surgery 1300 Rendcomb Surgery 1315 Sixways Surgery 1335 Arrive CGH 1345 Finish 1400 Cirencester Late Location