Norborne Berkeley's Politics.Indd 197 25/01/2012 09:55 198 William Evans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, a Descriptive Account of Each Place

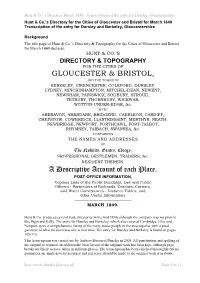

Hunt & Co.’s Directory March 1849 - Transcription of the entry for Dursley, Gloucestershire Hunt & Co.’s Directory for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 Transcription of the entry for Dursley and Berkeley, Gloucestershire Background The title page of Hunt & Co.’s Directory & Topography for the Cities of Gloucester and Bristol for March 1849 declares: HUNT & CO.'S DIRECTORY & TOPOGRAPHY FOR THE CITIES OF GLOUCESTER & BRISTOL, AND THE TOWNS OF BERKELEY, CIRENCESTER, COLEFORD, DURSLEY, LYDNEY, MINCHINHAMPTON, MITCHEL-DEAN, NEWENT, NEWNHAM, PAINSWICK, SODBURY, STROUD, TETBURY, THORNBURY, WICKWAR, WOTTON-UNDER-EDGE, &c. W1TH ABERAVON, ABERDARE, BRIDGEND, CAERLEON, CARDIFF, CHEPSTOW, COWBRIDCE, LLANTRISSAINT, MERTHYR, NEATH, NEWBRIDGE, NEWPORT, PORTHCAWL, PORT-TALBOT, RHYMNEY, TAIBACH, SWANSEA, &c. CONTAINING THE NAMES AND ADDRESSES OF The Nobility, Gentry, Clergy, PROFESSIONAL GENTLEMEN, TRADERS, &c. RESlDENT THEREIN. A Descriptive Account of each Place, POST-OFFICE INFORMATION, Copious Lists of the Public Buildings, Law and Public Officers - Particulars of Railroads, Coaches, Carriers, and Water Conveyances - Distance Tables, and other Useful Information. __________________________________________ MARCH 1849. ___________________________________________ Hunt & Co. produced several trade directories in the mid 1850s although the company was not prolific like Pigot and Kelly. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley, which also covered Cambridge, Uley and Newport, gave a comprehensive listing of the many trades people in the area together with a good gazetteer of what the town was like at that time. The entry for Dursley and Berkeley is found on pages 105-116. This transcription was carried out by Andrew Barton of Dursley in 2005. All punctuation and spelling of the original is retained. In addition the basic layout of the original work has been kept, although page breaks are likely to have fallen in different places. -

KINGSWOOD Village Design Statement Supplementary Information

KINGSWOOD Village Design Statement Supplementary Information 1 Contents Appendix 1 Community Assets and Facilities Appendix 2 Table of Organisations and Facilities within Kingswood Appendix 3 Fatal and Serious Accidents Kingswood Appendix 4 Fatal and serious Accidents Kingswood and Wotton-under-Edge Appendix 5 Wotton Road Charfield, August 2013 Appendix 6 Hillesley Road, Kingswood,Traffic Survey, September 2012 Appendix 7 Wickwar Road Traffic Survey Appendix 8 Kingswood Parish Council Parish Plan 2010 Appendix 9 List of Footpaths Appendix 10 Agricultural Land Classification Report June 2014 Appendix 11 Kingswood Playing Field Interpretation Report on Ground Investigation Appendix 12 Peer Review of Flood Risk Assessment Appendix 13 Kingswood Natural Environment Character Assessment Appendix 14 Village Design Statement Key Dates 2 Appendix 1 Community Assets and Facilities 3 Community Assets and Facilities Asset Use Location Ownership St Mary’s Church Worship High Street Church and Churchyard Closed Churchyard maintained by Kingswood parish Council The St Mary’s Room Community High Street Church Congregational Chapel Worship Congregational Chapel Kingswood Primary School Education Abbey Street Local Education Authority Lower School Room Education/ Worship Chapel Abbey Gateway Heritage Abbey Street English Heritage Dinneywicks Pub Recreation The Chipping Brewery B&F Gym and Coffee shop Sport and Recreation The Chipping Limited Company Spar Shop/Post Office Retail The Chipping Hairdressers Retail Wickwar Road All Types Roofing Retail High -

Journal Issue 3, May 2013

Stonehouse History Group Journal Issue 3 May 2013 ISSN 2050-0858 Published by Stonehouse History Group www.stonehousehistorygroup.org.uk [email protected] May 2013 ©Stonehouse History Group Front cover sketch “The Spa Inn c.1930” ©Darrell Webb. We have made every effort to obtain permission from the copyright owners to reproduce their photographs in this journal. Modern photographs are copyright Stonehouse History Group unless otherwise stated. No copies may be made of any photographs in this issue without the permission of Stonehouse History Group (SHG). Editorial Team Vicki Walker - Co-ordinating editor Jim Dickson - Production editor Shirley Dicker Janet Hudson John Peters Darrell Webb Why not become a member of our group? We aim to promote interest in the local history of Stonehouse. We research and store information about all aspects of the town’s history and have a large collection of photographs old and new. We make this available to the public via our website and through our regular meetings. We provide a programme of talks and events on a wide range of historical topics. We hold meetings on the second Wednesday of each month, usually in the Town Hall at 7:30pm. £1 members; £2 visitors; annual membership £5 2 Stonehouse History Group Journal Issue 3, May 2013 Contents Obituary of Les Pugh 4 Welcome to our third issue 5 Oldends: what’s in an ‘s’? by Janet Hudson 6 Spa Inn, Oldends Lane by Janet Hudson, Vicki Walker and Shirley Dicker 12 Oldends Hall by Janet Hudson 14 Stonehouse place names by Darrell Webb 20 Charles -

Pathology Van Route Information

Cotswold Early Location Location Depart Comments Start CGH 1000 Depart 1030 Depart 1040 if not (1005) going to Witney Windrush Health Centre Witney 1100 Lechlade Surgery 1125 Hilary Cottage Surgery, Fairford 1137 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1205 Moore Health Centre BOW 1218 George Moore Clinic BOW 1223 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1237 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1247 White House Surgery MIM 1252 Mann Cottage MIM 1255 Chipping Campden Surgery 1315 Barn Close MP Broadway 1330 Arrive CGH 1405 Finish 1415 Cotswold Late Location Location Depart Comments Start Time 1345 Depart CGH 1400 Abbey Medical Practice Evesham 1440 Merstow Green 1445 Riverside Surgery 1455 CGH 1530-1540 Westwood Surgery Northleach 1620 Moore Health Centre BOW 1635 Well Lane Surgery Stow 1655 North Cotswolds Hospital MIM 1705 White House Surgery M-in-M 1710 Mann Cottage MIM 1715 Chipping Campden Surgery 1735 Barn Close MP Broadway 1750 Winchcombe MP 1805 Cleeve Hill Nursing Home Winchcombe 1815 Arrive CGH 1830 Finish 1845 CONTROLLED DOCUMENT PHOTOCOPYING PROHIBITED Visor Route Information- GS DR 2016 Version: 3.30 Issued: 20th February 2019 Cirencester Early Location Location Depart Comments Start 1015 CGH – Pathology Reception 1030 Cirencester Hospital 1100-1115 Collect post & sort for GPs Tetbury Hospital 1145 Tetbury Surgery (Romney House) 1155 Cirencester Hospital 1220 Phoenix Surgery 1230 1,The Avenue, Cirencester 1240 1,St Peter's Rd., Cirencester 1250 The Park Surgery 1300 Rendcomb Surgery 1315 Sixways Surgery 1335 Arrive CGH 1345 Finish 1400 Cirencester Late Location -

Appendix 1 – Project Specification

Stroud District Council WORKING DRAFT REPORT Local Plan Viability Assessment – May 2021 Appendix 1 – Project Specification Specification 11.1 The District Council wishes to appoint consultants to undertake a Viability Assessment (VA) of the proposed Pre-Submission Local Plan, taking account of all policy and infrastructure requirements and all potential housing and commercial development in the District. The completed VA will form part of the evidence base for the Local Plan Review and help to demonstrate its deliverability. The VA will also review the current level of Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) and the level of affordable housing that would allow the funding of infrastructure and meet needs without putting at risk the economic viability of development in the District. 11.2 The consultant should use an established model or develop a bespoke model to test and appraise the impact of the Pre-Submission Local Plan on the viability of development, having regard to the requirements of the NPPF, as set out in paragraphs 34, 57 and 76 and national guidance contained within the NPPG. 11.3 The Assessment should review current residential and non-residential markets, land prices and development costs, together with planning policy requirements, including emerging zero carbon standards, different tenures of affordable housing needs and infrastructure required of development. A matrix of variables should be drawn from these assumptions. These may include but should not be limited to: · Varying market conditions over the 20 year period 2020 to 2040; · Varying Existing Use Values across the District, considering the land uses outlined in the site typologies; · Range of average dwelling sizes; · Infrastructure priorities; · CIL rates and operation of instalment policy; · Range of developer profit and yield assumptions; · Differing affordable housing tenure mixes. -

THE TEWKESBURY and CHELTENHAM ROADS A. Cossons

Reprinted from: Gloucestershire Society for Industrial Archaeology Journal for 1998 pages 40-46 THE TEWKESBURY AND CHELTENHAM ROADS A. Cossons The complicated nature of the history of the Tewkesbury turnpike trust and of its offshoot, the Cheltenham trust, makes it desirable to devote more space to it than that given in the notes to the schedules of Acts to most of the other roads. The story begins on 16 December 1721, when a petition was presented to the House of Commons from influential inhabitants of Tewkesbury, Ashchurch, Bredon, Didbrook, and many other places in the neighbourhood, stating that erecting of a Turnpike for repairing the Highways through the several Parishes aforesaid from the End of Berton-street, in Tewkesbury, to Coscombgate .......... is very necessary'. The petitioners asked for a Bill to authorize two turnpikes, one at Barton Street End, Tewkesbury, and one at Coscomb Gate, at the top of Stanway Hill. Two days later a committee reported that they had examined Joseph Jones and Thomas Smithson and were of the opinion that the roads through the several parishes mentioned in the petition 'are so very bad in the Wintertime, that they are almost impassable, and enough to stifle Man and Horse; and that Waggons cannot travel through the said Roads in the Sumer-time'. Leave was given to bring in a Bill and this was read for the first time the next day. During the period before the second reading was due, two petitions were presented on 23 January 1721-2, - one from Bredon, Eckington, etc., and the other from Pershore, Birlingham, and other places. -

Gloucestershire Parish Map

Gloucestershire Parish Map MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT MapKey NAME DISTRICT 1 Charlton Kings CP Cheltenham 91 Sevenhampton CP Cotswold 181 Frocester CP Stroud 2 Leckhampton CP Cheltenham 92 Sezincote CP Cotswold 182 Ham and Stone CP Stroud 3 Prestbury CP Cheltenham 93 Sherborne CP Cotswold 183 Hamfallow CP Stroud 4 Swindon CP Cheltenham 94 Shipton CP Cotswold 184 Hardwicke CP Stroud 5 Up Hatherley CP Cheltenham 95 Shipton Moyne CP Cotswold 185 Harescombe CP Stroud 6 Adlestrop CP Cotswold 96 Siddington CP Cotswold 186 Haresfield CP Stroud 7 Aldsworth CP Cotswold 97 Somerford Keynes CP Cotswold 187 Hillesley and Tresham CP Stroud 112 75 8 Ampney Crucis CP Cotswold 98 South Cerney CP Cotswold 188 Hinton CP Stroud 9 Ampney St. Mary CP Cotswold 99 Southrop CP Cotswold 189 Horsley CP Stroud 10 Ampney St. Peter CP Cotswold 100 Stow-on-the-Wold CP Cotswold 190 King's Stanley CP Stroud 13 11 Andoversford CP Cotswold 101 Swell CP Cotswold 191 Kingswood CP Stroud 12 Ashley CP Cotswold 102 Syde CP Cotswold 192 Leonard Stanley CP Stroud 13 Aston Subedge CP Cotswold 103 Temple Guiting CP Cotswold 193 Longney and Epney CP Stroud 89 111 53 14 Avening CP Cotswold 104 Tetbury CP Cotswold 194 Minchinhampton CP Stroud 116 15 Bagendon CP Cotswold 105 Tetbury Upton CP Cotswold 195 Miserden CP Stroud 16 Barnsley CP Cotswold 106 Todenham CP Cotswold 196 Moreton Valence CP Stroud 17 Barrington CP Cotswold 107 Turkdean CP Cotswold 197 Nailsworth CP Stroud 31 18 Batsford CP Cotswold 108 Upper Rissington CP Cotswold 198 North Nibley CP Stroud 19 Baunton -

Gloucestershire. [Kelly's

432 BOO GLOUCESTERSHIRE. [KELLY'S BOOT & SHOE MAKER8-Continued. BOTTLE MANUFACTURERS- Carpenter & Co. Cainscross brewery, Trinder Alfred Harris, Campden S.O GLASS. Cainscross, Stroud TrinderW. Wit~ingtn.Andovrsfrd.R~. 0 Kilner Brothers, Great Northern Railway Cheltenha.m Orig~nal Brewery ~o. ~im. TruebodyW.Brldge Yate,Warmly.B1'lstl goods station KiuO"s cross London N (Arthur In. Shmner, managlllg dlrec- Tucker Alfred, Cinderford, Newnham 'b' tor; C. O. Webb, sec.), 160 High Turner E. & Co.Lim.7 Dyerst.Cirencstr BOTTLE BOX & CASE MKRS. street, Cheltenham Turner Ralph, 4 Gordon terrace, Sher- Kilner Brothers,Great Northern Railway Cirencester Brewery Lim. (T. Matthews, borne place, Cheltenham goods station, King's cross, London N sec.), Cricklade street, Cirencester Tyler George, 23 Middle street, Stroud Combe Benjamin, Grafton brewery, Tyler John, 161 Cricklade st.Cirencester BOTTLERS. Grafton road, Cheltenham Tyler William Henry,3 Nelson st.Strond See Ale & Porter Merchants & Agents. Combe GeorgeThomas, Brockhampton, Underhill Henry, Cinderford, Newnham Andoversford RS.O Underwood lsaac, Avening, Stroud BRASS FINISHERS. Cook ReginaldH. &Nathaniel &WaIter, Vick James, Barbican road, Gloucester Haines T. 2 Clare st. Bath I'd. Cheltnhm Hampton street, Tetbury Viner James, 2 Painswick parade, Thornton F. Oxford passage, Cheltnhm Coombe Valley Brewery, Coombe, Painswick road, Cheltenham Wynn E. 51 St. George's pI. Cheltenhm Wotton-under-Edge Virgo Joseph, Micheldean RS.O Wynn G. H. St. James' sq. Cheltenham Cordwell & Bigg, HamweIl Leaze Ward Mrs.A.Welford, Stratford-on-Avn brewery, Cainscross, Stroud Watkins :Fredk. Gloucester I'd. Coleford BRASS FOUNDERS. Davis Joseph, Portcullis hotel, Great ',:atkins J. Pi~lowell, Y?rkley, Lydney Gloucester Brass foundry (John Higgins, Badminton S.O . -

Gloucestershire. Nuh 497 Nail Makers

TRADES DIRECTORY.] GLOUCESTERSHIRE. NUH 497 NAIL MAKERS. I NEWSPAPERS Tewkesbury Register (William North, Buncombe Arthur Henry (dealer) (late . printer ~ publisher; published sJ.tur- Hy.Buncombe),Cricklade st.Cirencst Berkele:y, Dursley & Sharpness Gazette day), HIgh street, Tewkesbury .. George Wm. Little Dean, Newnham (publIshed saturdays; W. Hatten, Tewkesbury Weekly Record (WIlham Griffiths In. Abinghall,MicheldeanR.S.O agent), Salter ~tr~t, Berkel~y Ja:mes Gardner, proprietor, published Griffiths T. Abinghall, MicheldeanR.S.O Bourton Vale &DIstrIct ~dvertlser(~ras. frIday), 7 ~artou street,.Te~kesbury Gwilliam Henry, Little Dean,Newnham George Serman, publIsher; pubhsned Western Dally. P~ess (dIstrIct o~ce) Gwilliam Jeremiah, Chalford, Stroud sat.), Bourton-on-the-Water R.S.O (Frank W. HIggmS,. manager),Kmgs- Gwynne Thos. 62 Castle st. Cirencester British Mercur~(J o.hn HerbertWilliams, ~ood, Bristol . Hooper John, Leighterton, Wotton- manager), dIS~rIct office, Regent st. WIlts & GloucestershIre Sta?-dard under-Edge Kingswood, BrlStol (George Henry Harmer, pubhsher; Sadler Joseph, Greenway, Ledbury Cheltenham Chr?nicle(FrederickJoseph publishe~ saturday); office, Dyer Bennett, publIsher: published sat.), street, Clrencester. See advert NAPHTHA MANUFACTRS. Clarence par. C~eltenhm. See advert NEWSPAPER REPORTERS. Butler William & Co. Upper Parting Cheltenham.Exammer (Norman &Saw- . works Sandhurst Gloucester yer, publIshers; pnblished wed.), 9 CHhl;\rleYJJamesSmlth'dBlaksenoey,Newnhm " Clarence st. Cheltenham. See advert ames ames, Camp en . Cheltenham Free Press &Cotswold News Parsons Francis, 7 North pl.Cheltenhm NATURALISTS. (Norman &Sawyer, publishers; pub- U~d~rhill E.J.High st.ThornburyR.S.O See Bird & Animal Preservers. lished saturday), 9 Clarence street, WlllId.ms George Mansell, St. John Cheltenham. See advert street, Thornbury R.S.O NEWSAGENTS. -

(OTE) February

ISSUE 269 ON THE EDGE FEBRUARY 2021 Alison’s Tree-mendous Birthday Challenge In celebration and gratitude for 70 wonderful years of family, friendship, love and life on our awesome planet, (over half of which I realise have been spent in North Nibley), I have set myself a birthday challenge. The challenge is to encourage the planting of trees; specifically 700 in North Nibley Parish in the next 12 months and also in the wider world. An initial post on the North Nibley Community Facebook page generated an encouraging response, including offers of various saplings, which have now been directed to good homes, where I hope they will grow and flourish. I plan to create a record, so if you do choose to join in, let me know what you do and I will add you and your contribution to the Roll of Honour! To date some 40 trees have been recently planted in Nibley including 30 hazel saplings, an oak, apples, cherries , plums and a liquidambar. It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by the environmental crisis, but we can all make an individual contribution in some way…. And although you can count the seeds in an apple, you can never know how many apples will grow from those seeds……Let’s get planting. (Alison Beer above) [email protected] tel 01453 546251 text 07765869412 or via Facebook Messenger. There are a number of ways you can support this challenge - see back Thank you, Dr. Edward Jenner 2021 is the year of hope. The the public, lovingly cared for, and year when the world will start to offer informative and educational recover from the threat of the Covid- displays and events about the 19 virus which has blighted 2020. -

Overview Bus Routes to Stroud 2018-2019 Sixth Form

Stroud High 2018-2019 Overview Bus Routes to Stroud Sixth Form ROUTE ROUTE STOPS COMPANY NUMBER Arlingham; Overton Lane; Frampton (The Bell/Vicarage Lane); Eastington (Claypits); Stonehouse (Court Hotel); Arlingham-Frampton-Eastington-Stonehouse M KB Coaches Stroud (SHS) Bourne; Chalford Hill; Abnash; Bussage Bourne; Chalford Hill; Abnash; Bussage; Stroud (SHS) ROV1/2 Rover Box-Amberley-Rodborough Box (Halfway House); Amberley (Amberley Inn); Rodbrough (Bear); Rodborough (King's Road); Stroud (SHS) 127 Cotswold Green Cheltenham-Shurdington-Brokworth-Cranham- Cheltenham Promenade/Hospital); Shurdington (Church Lane); Brockworth(Garage); Cranham (Royal William); 61/61A Stagecoach Painswick-Paganhill-Stroud Bus Station Painswick (St. Mary's Church); Paganhill (Church of Holy Spirit/Archway School); Stroud (Bus Station) Cirencester-Coates Cirencester; Chesterton Lane; Coates; Stroud (SHS) ROVB Rover Cirencester-Coates-Sapperton-Frampton Cirencester (Parish Church/Chesterton Lane/Deer Park); Sapperton (The Glebe); Frampton Mansell (St. Lukes/White 54/54A/X54 Cotswold Green Mansell-Chalford-Brimscombe Horse Inn); Chalford (Marle Hill); Brimscombe (War Memorial; Stroud (Merrywalks) Lechlade-Fairford- Cirencester-Stroud Cirencester; Stroud (SHS) ROVA Rover Forest Green (Primary School/Star Hill/Moffatt Road/Northfield Road); Nailsworth (Bus Station); Innchrook (Dunkirk Forest Green-Nailsworth-Inchbrook 3 Ebley Coaches Mills/Trading Estate); Stroud (SHS) Hardwicke (One Stop Shop); Quedgeley (Telephone Exchange); Colethrop (Cross Farm); Harefield -

620 from Bath to Pucklechurch, Yate & Old Sodbury 69 from Stroud To

620 from Bath to Pucklechurch, Yate & Old Sodbury 69 from Stroud to Minchinhampton, Tetbury & Old Sodbury 26th November 2018 69 from Old Sodbury, Tetbury & Minchinhampton to Stroud 620 from Old Sodbury, Yate & Pucklechurch to Bath Mondays to Saturdays Mondays to Saturdays MF MF MF 620 620 620 620 620 620 620 620 69 69 69 69 69 69 69 69 69 Bath Bus Station [3] 0730 0735 1035 1335 1335 1645 1745 1845 Stroud Merrywalks [K] 0805 0805 1005 1105 1405 1405 1625 1735 Lansdown Blatwayt Arms 0745 0750 1050 1350 1350 1700 1800 1900 Stroud Bus Depot 0610 - - 1010 1110 1410 1410 1630 1740 Wick Rose & Crown 0752 0757 1057 1357 1357 1707 1807 1907 Rodborough Bear Inn - 0814 0814 - - - - - - Pucklechurch Fleur de Lys 0804 0809 1109 1409 1409 1719 1819 1919 Minchinhampton Ricardo Rd 0620 0820 0820 - 1120 1420 1420 - 1750 Westerleigh Broad Lane 0811 - - - - - - - Minchinhampton Square 0623 0823 0823 1023 1123 1423 1423 1643 1753 Westerleigh War Memorial 0812 0815 1115 1415 1415 1725 1825 1925 Box Halfway House Inn - - - 1027 - - - 1647 - Yate International Academy 0818 - - - - - - - Nailsworth Bus Station [2] - - - 1032 - - - 1652 - Yate Goldcrest Road - 0821 1121 1421 1421 1731 1831 1931 Hampton Fields Gatcombe Cnr 0629 0829 0829 - 1129 1429 1429 1759 Yate Shopping Centre [B] 0821 0826 1126 1426 1426 1736 1836 1936 Avening Mays Lane 0632 0832 0832 1042 1132 1432 1432 1802 Yate Shopping Centre [B] 0825 0830 1130 1430 1430 1740 1840 1940 Tetbury Sir William Romney School - 0840 - - - - - - Chipping Sodbury School 0830 - - - - - - - Tetbury Tesco 0643 - 0843