A Vision for the Future of Non-Binary Fashion on Video: Trans-Animal Conceptual Sculpture Performance Explorations By

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NASCIMENTO, Juliana. Drags Demônias – O Grupo Cultural Belemense Em Análise

NASCIMENTO, Juliana. Drags Demônias – O Grupo Cultural Belemense em Análise. Belém: PPGArtes. ICA – UFPa; Mestranda; Wladilene Lima. Bolsista CAPES. Drag e Pesquisadora. RESUMO: Desde 2014, na cidade de Belém, o grupo cultural que se auto identifica com o nome “Drags Demônias” tem quebrado diversos paradigmas que rodeiam a arte drag; reagindo artisticamente de acordo com uma construção filosófica e atravessamentos específicos. Em um primeiro momento organiza-se através de um estudo bibliográfico e análise através de história oral, seguido de um estudo dos conceitos que conversam com a arte drag (como drag queen, drag king, drag queer, transformista, cross-dresser, travesti, transgêneros, etc.) e revisitando algumas confusões e alterações dessas estruturas conceituais e convergindo com a produção contemporânea. Partindo para um segundo momento onde, através de observação e análise, identifica-se a gênese do grupo como subgênero direto da arte Drag Queer. Partindo do princípio que esta consiste na não-definição de um gênero específico na sua construção poética; abrindo novas possibilidades de atravessamentos, percepções e estéticas. A Demônia, muito além da estética e do sincretismo cristão, remete ao demônio interior, ao grego daimon, ao destino – ethos anthropo daimon. Além de alimentar arcabouço teórico sobre o tema e suas transgressões e variações. PALAVRAS CHAVE: Drag, Demônia, Queer, Belém. ABSTRACT: Since 2014, in Belém, the cultural group that identifies itself with the name "Drags Demônias" has broken several paradigms that surround the drag art; reacting artistically according to a philosophical construction and specific crossings. At first it is organized through a bibliographic study and analysis through oral history, followed by a study of the concepts that talks with the drag art (as drag queen, drag king, drag queer, transformista, cross-dresser, travesti, transgenders, etc.) and revisiting some confusions and alterations of these conceptual structures and converging with contemporary production. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

Tom Rubnitz / Dynasty Handbag

TOM RUBNITZ / DYNASTY HANDBAG 9/25/2012 PROGRAM: TOM RUBNITZ The Mother Show, video, 4 mins., 1991 Made for TV, video, 15 mins., 1984 Drag Queen Marathon, video, 5 mins., 1986 Strawberry Shortcut, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 Pickle Surprise, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 DYNASTY HANDBAG The Quiet Storm (with Hedia Maron), video, 10 mins., 2007 Eternal Quadrangle, video, 20 mins., 2012 WHITE COLUMNS JIBZ CAMERON JOSH LUBIN-LEVY What does it mean to be a great performer? In a rather conventional sense, great performing is often associated with a sense of interiority, becoming your character, identifying with your role. In that sense, a great performer could become anyone else simply by looking deep within herself. Of course, there’s a long history of performance practices that reject this model. Yet whether it is a matter of embracing or rejecting what is, so to speak, on the inside, there is an overarching belief that great performers are uniquely adept at locating themselves and using that self to build a world around them. It is no surprise then that today we are all expected to be great performers. Our lives are filled the endless capacity to shed one skin for another, to produce multiple cyber-personalities on a whim. We are hyperaware that our outsides are malleable and performative—and that our insides might be an endless resource for reinventing and rethinking ourselves (not to mention the world around us). So perhaps it’s almost too obvious to say that Jibz When I was a youth, say, about 8, I played a game in the Cameron, the mastermind behind Dynasty Handbag, is an incredible woods with my friend Ocean where we pretended to be hookers. -

View Entire Issue As

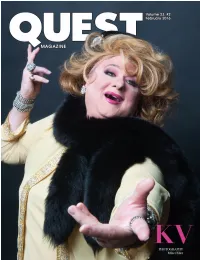

Karen Valentine Photographer Mike Hiller Stylist Dawn Marie Weeden Such A Keen Eye Make Up/Hair Goldie Adams Assistants Roger Ram Jet, Kelly Klawes A special thank you to La Cage for use of their venue. Spice. I knew Dear Ruthie from her col - aside from costuming and the make-up umn. We were already friends socially and brush. I respect people who cut off their Karen I extended an invitation for her to do her dicks but I’ve had too much fun with mine. first drag show at M&Ms. We played the But, in today’s world it’s more of a blur. In Valentine little girls from Little Rock. It went over big the past, the excitement was seeing the and we followed with solo numbers. From transformation from boy to girl. Now the An Interview by Paul Masterson there her career went on both as a writer transformation isn’t as startling. Some re - for Wisconsin Light and as a drag mind me of Julie Newmar doing My Living In the Pantheon of Milwaukee drag god - performer. Doll . They’re robotic. It’s beyond skin. desses, Karen Valentine takes her place in the upper most rank. Her decades’ long PM: And what about you? I don’t use the “f” bomb or “cs” references, commitment to the LGBT community is either. Karen is above that. There was a marked by her dedication to a broad spec - KV: I made friends with the legendary drag complaint once about the double enten - trum of causes and organizations. -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today. -

GAG Magazine

SPECIAl ISSUE CONTENTS SPECIAL ISSUE ON THE COVER: THE ART OF GAG A retrospective celebration of GAG and a peek into our future. PAGE 20 5 // Musings from the Editrix 6 // Back Talk 8 // Gagging On with special guest Chiffon Dior LIFE 10 // Libations by Candace Collins 12 // Ask Edna Jean 14 // Voices Trans* Drag by Freddy Prinze Charming 72 // Drag-o-sphere 74 // Spotlight: Fans ART 16 // The Art of Drag: The Making of a King Documentary An interview with woman behind the kings, Nicole Miyahara. 66 // Extravaganza The Austin International Drag Festival GAG sits down with the mastermind behind the world’s first 4 day drag festival. BRANDI AMARA SKYY EDITIRX PAUL MICHAEL ARMSTRONG CREATIVE DIRECTOR CONTRIBUTORS Candace Collins Chiffon Dior Freddy Prinze Charming Edna Jean Robinson PHOTOGRAPHERS Alex Craddock Austin Young AJ Bates photography Cher Musico/Roots Photography Edwin Irizarry Gabe King Photography Jose A. Guzman Colon Kristofer Reynolds of kristoferreynolds.com Marcelo Cantu Photography Mathu Anderson Mei Na Nicole Miyahara Photography by Suri Rosemary Photography Robert Stahl musings from the editirx This issue of GAG is special not only because we are celebrating our second birthday, but because we’re in the middle of a growth spurt. We’ve outgrown some things . Departments like News, Music, Library, DID (Dipping into Drag). And grown into others . Voices where YOU write the story; The Art of Drag where we highlight others like us who are creating spectacular things; and - my personal favorite - Spotlight where we dedicate the last page(s) of the magazine to shining the spotlight on those who make us stars - the fans. -

Lgbtq Abyss Zignego Ready Mix, Inc

Democratic Socialists of America: Communism for the New Millennium • The Racist American Flag? August 5 , 2019 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH “DRAG”ING KIDS INTO THE LGBTQ ABYSS ZIGNEGO READY MIX, INC. W226 N2940 DUPLAINVILLE ROAD WAUKESHA, WI 53186 262-542-0333 • www.Zignego.com RESCUING OUR CHILDREN SUMMER TOUR 2019 WITH ALEX NEWMAN There is a reason the Deep State globalists sound so confident about the success of their agenda — they have a secret weapon: More than 85 percent of American children are being indoctrinated by radicalized government schools. In this explosive talk, Alex Newman exposes the insanity that has taken over the public school system. From the sexualization of children and the reshaping of values to deliberate dumbing down, Alex shows how dangerous this threat is — not just to our children, but also to the future of faith, family, and freedom — and what every American can do about it. VIRGINIA OREGON ✔ May 27 / Hampton / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 ✔ July 10 / King City / Sally Crino / 503-522-3926 ✔ May 29 / Chesapeake / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 WASHINGTON ✔ May 30 / Richmond / Thomas Redfern / 804-722-1084 ✔ July 12 & 13 / Spokane / Caleb Collier / 509-999-0479 ✔ June 4 / Falls Church / Tricia Stall / 757-897-4842 ✔ July 14 / Lynnwood (Seattle) / Lillian Erickson / 425-269-9991 CONNECTICUT CALIFORNIA ✔ June 7 / Hartford / Imani Mamalution / 860-983-5279 ✔ July 18 / Lodi / Greg Goehring / 209-712-1635 ✔ June 8 / Hartford / Imani Mamalution / 860-983-5279 ✔ July 23 / Thousand Oaks -

E Past, Present and Future of Drag in Los Angeles

Rap Duo 88Glam embrace Hip-Hop’s fearlessness • Museum Spotlights Ernie Barnes, Artist and Athlete ® MAY 24-30, 2019 / VOL. 41 / NO. 27 / LAWEEKLY.COM Q e Past,UEENDOM Present and Future of Drag in Los Angeles BY MICHAEL COOPER AND LINA LECARO 2 WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM | - , | LA WEEKLY L May 24 - May 30, 2019 // Vol. 41 // No. 27 // laweekly.com 3 LA WEEKLY LA Explore the Country’s Premier School of Archetypal and Depth Psychology Contents - , | | Join us on campus in Santa Barbara WWW.LAWEEKLY.COM Friday, June 7, 2019 The Pacifica Experience A Comprehensive One-Day Introduction to Pacifica’s Master’s and Doctoral Degree Programs Join us for our Information Day and learn about our various degree programs. Faculty from each of the programs will be hosting program-specific information sessions throughout the day. Don't miss out on this event! Pacifica is an accredited graduate school offering degrees in Clinical Psychology, Counseling Psychology, the Humanities and Mythological Studies. The Institute has two beautiful campuses in Santa Barbara nestled between the foothills and the Pacific Ocean. All of Pacifica’s degree programs are offered through monthly three-day learning sessions that take into account vocational, family, and other commitments. Students come to Pacifica from diverse backgrounds in pursuit of an expansive mix of accademic, professional, and personal goals. 7 Experience Pacifica’s unique interdisciplinary degree programs GO LA...4 FILM...16 led by our renowned faculty. Celebrate punk history, explore the NATHANIEL BELL explores the movies opening Tour both of our beautiful campuses including the Joseph Campbell Archives and the Research Library. -

The Haus of Frau: Radical Drag Queens Disrupting the Visual Fiction of Gendered Appearances

The Haus of Frau: Radical Drag Queens Disrupting the Visual Fiction of Gendered Appearances John Bryan Jacob Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Clothing and Textiles Catherine Cerny, Co-Chair Ann Kilkelly, Co-Chair Katherine Allen Scott Christianson Valerie Giddings Rebecca Lovingood May 7, 1999 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Gender, Appearance, Identity, Gay Studies, Women’s Studies Copyright 1999, John Bryan Jacob THE HAUS OF FRAU: RADICAL DRAG QUEENS DISRUPTING THE VISUAL FICTION OF GENDERED APPEARANCES John Bryan Jacob (ABSTRACT) This research considers the connections between appearance and identity apparent in the social experience of five gay male drag queens. Appearing at variance with gender norms that underwrite male appearance in mainstream society and among gay men prompted social consequences that impacted their identities and world views. One aim is to apprehend the experiences of difference that drag appearance manifest and expressed. Another aim is to gain a new perspective on the social construction of gendered appearances from marginalized persons who seem to look from the “outside” in toward mainstream social appearances and relations. Qualitative analysis relied on interview data and occurred using grounded theory methodology However, analysis gained focus and intensified by engaging Stone’s (1970) theorizing on “Appearance and the Self,” Feminist articulations of “the gaze” and poststructural conceptions of the discursively constituted person as “the subject.” This research especially emphasizes the points of connection between Stone’s theorizing and more recent feminist theoretical advancements on the gaze as they each pertain to appearance, identity and social operations of seeing and being seen. -

The Gentrification of Drag

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works Capstones Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism Fall 12-16-2018 The Gentrification of Drag Kyle Kucharski Cuny Graduate School of Journalism How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gj_etds/294 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] The Gentrification of Drag How drag refuses to lose its edge in mainstream entertainment By Kyle Kucharski Drag culture is blowing up the mainstream. What has historically been a queer subculture relegated to the nightlife world is now an emerging arena of entertainment on primetime television. Reality TV shows like “RuPaul’s Drag Race” have changed the drag landscape forever, bringing it into the center of the cultural conversation, where it can be made into family-friendly, PG-13 programming. An ever-growing thirst for more drag content means more opportunities for performers to make careers, more money for those performers and more varied and dynamic art. But what is the cost of the commercial monetization of an audacious, queer form of performance born on the margins of society and fueled by the underground? In response to this, a growing community of performers—many of them quite new to drag—have created a space for their own type of art, one that attempts to keep drag underground. Their work suggests that if the value of drag lies in its power to shock and to provide a dissenting critique on heterosexual, cisgender culture, its power as a subversive form of art is lost when its mass-produced and inevitably sanitized. -

CORONAVIRUS OPENS EYES to HOMESCHOOLING D�Amond M Ranc

Climate Crusaders Yet Carbon Creators • World Health Organization Is Communist May 4, 2020 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com CORONAVIRUS OPENS EYES TO HOMESCHOOLING Diamond M Ranch REGISTERED & COMMERCIAL HEREFORDS Range Bulls, Replacement Females, Stocker & Feeder Cattle (one or a truckload) A Fifth Generation Ranching Family Engaged In Accenting The Hereford Influence Box 99 The Diamond M Ranch Family 646 Lake Rd. Laurier, WA 99146 Len & Pat McIrvin Burbank, WA 99323 Len: 509/684-4380 Bill & Roberta McIrvin Len: 509/545-5676 (Summer phone) Justin & Kaleigh Hedrick (Winter phone & address) Mason & Natasha Knapp “This is a republic, not a democracy — Let’s keep it that way!” Spread Coronavirus Opens Eyes to Homeschooling Word Under the coronavirus lockdowns, THE there are now tens of millions of homeschoolers. Homeschool groups hope this seismic shift will result in droves joining the movement long-term. (May 4, 2020, 48pp) TNA200504 SPECIAL REPORT April 20, 2020 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH CHECK OUT OUR OTHER ISSUES! Next Step to World Coronavirus: Freedom Trimming Big Government: Freeing the Web Is Medicare for All Is the Cure Government Atlantic Union From Big Tech the Cure-all? Worldwide, including in the Donald Trump was elected Trade agreements between One’s habits, purchases, beliefs, Democrats are pushing United States, governments’ on promises to streamline countries across the Atlantic sound and associates are monitored Medicare for All, despite its answer to the COVID-19 and cut costs in government. like smart propositions to boost on the Web by both Big Tech and massive costs, the failures pandemic is to eliminate personal While the streamlining may be economic growth, but the Atlantic Big Government, but there is a of similar healthcare freedoms. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading Rupaul's Drag Race

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 © Copyright by Carl Douglas Schottmiller 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Reading RuPaul’s Drag Race: Queer Memory, Camp Capitalism, and RuPaul’s Drag Empire by Carl Douglas Schottmiller Doctor of Philosophy in Culture and Performance University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor David H Gere, Chair This dissertation undertakes an interdisciplinary study of the competitive reality television show RuPaul’s Drag Race, drawing upon approaches and perspectives from LGBT Studies, Media Studies, Gender Studies, Cultural Studies, and Performance Studies. Hosted by veteran drag performer RuPaul, Drag Race features drag queen entertainers vying for the title of “America’s Next Drag Superstar.” Since premiering in 2009, the show has become a queer cultural phenomenon that successfully commodifies and markets Camp and drag performance to television audiences at heretofore unprecedented levels. Over its nine seasons, the show has provided more than 100 drag queen artists with a platform to showcase their talents, and the Drag Race franchise has expanded to include multiple television series and interactive live events. The RuPaul’s Drag Race phenomenon provides researchers with invaluable opportunities not only to consider the function of drag in the 21st Century, but also to explore the cultural and economic ramifications of this reality television franchise. ii While most scholars analyze RuPaul’s Drag Race primarily through content analysis of the aired television episodes, this dissertation combines content analysis with ethnography in order to connect the television show to tangible practices among fans and effects within drag communities.