Bridget Boyle Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

98Th ISPA Congress Melbourne Australia May 30 – June 4, 2016 Reimagining Contents

98th ISPA Congress MELBOURNE AUSTRALIA MAY 30 – JUNE 4, 2016 REIMAGINING CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE & COUNTRY 2 MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, 3 STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 4 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR OF PROGRAMMING, ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 5 MESSAGE FROM THE CHAIR, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 6 MESSAGE FROM THE CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER, INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS (ISPA) 7 LET THE COUNTDOWN BEGIN: A SHORT HISTORY OF ISPA 8 MELBOURNE, AUSTRALIA 10 CONGRESS VENUES 11 TRANSPORT 12 PRACTICAL INFORMATION 13 ISPA UP LATE 14 WHERE TO EAT & DRINK 15 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE 16 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 18 THE ANTHONY FIELD ACADEMY SPEAKERS 22 CONGRESS SCHEDULE OF EVENTS 28 CONGRESS PERFORMANCES 37 CONGRESS AWARD WINNERS 42 CONGRESS SESSION SPEAKERS & MODERATORS 44 THE ISPA FELLOWSHIP CHALLENGE 56 2016 FELLOWSHIP PROGRAMS 57 ISPA FELLOWSHIP RECIPIENTS 58 ISPA STAR MEMBERS 59 ISPA OUT ON THE TOWN SCHEDULE 60 SPONSOR ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 66 ISPA CREDITS 67 ARTS CENTRE MELBOURNE CREDITS 68 We are committed to ensuring that everyone has the opportunity to become immersed in ISPA Melbourne. To help us make the most of your experience, please ask us about Access during the Congress. Cover image and all REIMAGINING images from Chunky Move’s AORTA (2013) / Photo: Jeff Busby ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF PEOPLE MESSAGE FROM THE MINISTER FOR & COUNTRY CREATIVE INDUSTRIES, Arts Centre Melbourne respectfully acknowledges STATE GOVERNMENT OF VICTORIA the traditional owners and custodians of the land on Whether you’ve come from near or far, I welcome all which the 98th International Society for the Performing delegates to the 2016 ISPA Congress, to Australia’s Arts (ISPA) Congress is held, the Wurundjeri and creative state and to the world’s most liveable city. -

Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES the ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’S Done with ‘Drag Race’

Drag Syndrome Barred From Tanglefoot: Discrimination or Protection? A Guide to the Upcoming Democratic Presidential Kentucky Marriage Battle LGBTQ Debates Bianca Del Rio Floats Too, B*TCHES The ‘Clown in a Gown’ Talks Death-Drop Disdain and Why She’s Done with ‘Drag Race’ PRIDESOURCE.COM SEPT.SEPT. 12, 12, 2019 2019 | | VOL. VOL. 2737 2737 | FREE New Location The Henry • Dearborn 300 Town Center Drive FREE PARKING Great Prizes! Including 5 Weekend Join Us For An Afternoon Celebration with Getaways Equality-Minded Businesses and Services Free Brunch Sunday, Oct. 13 Over 90 Equality Vendors Complimentary Continental Brunch Begins 11 a.m. Expo Open Noon to 4 p.m. • Free Parking Fashion Show 1:30 p.m. 2019 Sponsors 300 Town Center Drive, Dearborn, Michigan Party Rentals B. Ella Bridal $5 Advance / $10 at door Family Group Rates Call 734-293-7200 x. 101 email: [email protected] Tickets Available at: MiLGBTWedding.com VOL. 2737 • SEPT. 12 2019 ISSUE 1123 PRIDE SOURCE MEDIA GROUP 20222 Farmington Rd., Livonia, Michigan 48152 Phone 734.293.7200 PUBLISHERS Susan Horowitz & Jan Stevenson EDITORIAL 22 Editor in Chief Susan Horowitz, 734.293.7200 x 102 [email protected] Entertainment Editor Chris Azzopardi, 734.293.7200 x 106 [email protected] News & Feature Editor Eve Kucharski, 734.293.7200 x 105 [email protected] 12 10 News & Feature Writers Michelle Brown, Ellen Knoppow, Jason A. Michael, Drew Howard, Jonathan Thurston CREATIVE Webmaster & MIS Director Kevin Bryant, [email protected] Columnists Charles Alexander, -

30 Years of Awgie Award Winners

AWG SPECIAL AWARD WINNERS 1973 - 2019 Special Awards The Dorothy Crawford Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Profession and the Industry The Fred Parsons Award for Outstanding Contribution to Australian Comedy The Richard Lane Award for Outstanding Service and Dedication to the Australian Writers' Guild The Hector Crawford Award For Outstanding Contribution to the Craft as a Script Producer, Editor or Dramaturg Australian Writers’ Guild Lifetime Achievement Award, proudly presented by Foxtel David Williamson Prize - Given in Celebration and Recognition of Excellence in Writing for Australian Theatre AWG Awards Monte Miller Award 1972 to 2006 Monte Miller Award - Long Form Monte Miller Award - Short Form John Hinde Award for Excellence in Science-Fiction Writing Life Membership Life Members Previous Awards Foxtel Fellowship - In Recognition of a Significant and Impressive Body of Work (2007-2014) Kit Denton Fellowship For Courage and Excellence in Performance Writing (2007-2012) CAL Peer Recognition Prize - Awarded to Major AWGIE Winner (2008-2010) Richard Wherrett Prize - Recognising Excellence in Australian Playwriting (2007-2009) Ian Reed Award for Best Script by a First-Time Radio Writer (1998-2000) Australian Writers' Foundation Playwriting Award (2014-2015) The Dorothy Crawford Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Profession and the Industry Previously The Dorothy Crawford Award for Outstanding Contribution to the Profession (1984-2018) 1984 Carmel Powers 1985 Katherine Brisbane 1986 Betty Burstall 1987 Hector Crawford -

Tom Rubnitz / Dynasty Handbag

TOM RUBNITZ / DYNASTY HANDBAG 9/25/2012 PROGRAM: TOM RUBNITZ The Mother Show, video, 4 mins., 1991 Made for TV, video, 15 mins., 1984 Drag Queen Marathon, video, 5 mins., 1986 Strawberry Shortcut, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 Pickle Surprise, video, 1:30 mins., 1989 DYNASTY HANDBAG The Quiet Storm (with Hedia Maron), video, 10 mins., 2007 Eternal Quadrangle, video, 20 mins., 2012 WHITE COLUMNS JIBZ CAMERON JOSH LUBIN-LEVY What does it mean to be a great performer? In a rather conventional sense, great performing is often associated with a sense of interiority, becoming your character, identifying with your role. In that sense, a great performer could become anyone else simply by looking deep within herself. Of course, there’s a long history of performance practices that reject this model. Yet whether it is a matter of embracing or rejecting what is, so to speak, on the inside, there is an overarching belief that great performers are uniquely adept at locating themselves and using that self to build a world around them. It is no surprise then that today we are all expected to be great performers. Our lives are filled the endless capacity to shed one skin for another, to produce multiple cyber-personalities on a whim. We are hyperaware that our outsides are malleable and performative—and that our insides might be an endless resource for reinventing and rethinking ourselves (not to mention the world around us). So perhaps it’s almost too obvious to say that Jibz When I was a youth, say, about 8, I played a game in the Cameron, the mastermind behind Dynasty Handbag, is an incredible woods with my friend Ocean where we pretended to be hookers. -

CHICAGO to Tour Australia in 2009 with a Stellar Cast

MEDIA RELEASE Embargoed until 6pm November 12, 2008 We had it coming…CHICAGO to tour Australia in 2009 with a stellar cast Australia, prepare yourself for the razzle-dazzle of the hit musical Chicago, set to tour nationally throughout 2009 following a Gala Opening at Brisbane‟s Lyric Theatre, QPAC. Winner of six Tony Awards®, two Olivier Awards, a Grammy® and thousands of standing ovations, Chicago is Broadway‟s longest-running Musical Revival and the longest running American Musical every to play the West End. It is nearly a decade since the “story of murder, greed, corruption, violence, exploitation, adultery and treachery” played in Australia. Known for its sizzling score and sensational choreography, Chicago is the story of a nightclub dancer, a smooth talking lawyer and a cell block of sin and merry murderesses. Producer John Frost today announced his stellar cast: Caroline O’Connor as Velma Kelly, Sharon Millerchip as Roxie Hart, Craig McLachlan as Billy Flynn, and Gina Riley as Matron “Mama” Morton. “I‟m thrilled to bring back to the Australian stage this wonderful musical, especially with the extraordinary cast we have assembled. Velma Kelly is the role which took Caroline O‟Connor to Broadway for the first time, and her legion of fans will, I‟m sure, be overjoyed to see her perform it once again. Sharon Millerchip has previously played Velma in Chicago ten years ago, and since has won awards for her many musical theatre roles. She will be an astonishing Roxie. Craig McLachlan blew us all away with his incredible audition, and he‟s going to astound people with his talent as a musical theatre performer. -

View Entire Issue As

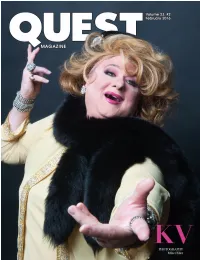

Karen Valentine Photographer Mike Hiller Stylist Dawn Marie Weeden Such A Keen Eye Make Up/Hair Goldie Adams Assistants Roger Ram Jet, Kelly Klawes A special thank you to La Cage for use of their venue. Spice. I knew Dear Ruthie from her col - aside from costuming and the make-up umn. We were already friends socially and brush. I respect people who cut off their Karen I extended an invitation for her to do her dicks but I’ve had too much fun with mine. first drag show at M&Ms. We played the But, in today’s world it’s more of a blur. In Valentine little girls from Little Rock. It went over big the past, the excitement was seeing the and we followed with solo numbers. From transformation from boy to girl. Now the An Interview by Paul Masterson there her career went on both as a writer transformation isn’t as startling. Some re - for Wisconsin Light and as a drag mind me of Julie Newmar doing My Living In the Pantheon of Milwaukee drag god - performer. Doll . They’re robotic. It’s beyond skin. desses, Karen Valentine takes her place in the upper most rank. Her decades’ long PM: And what about you? I don’t use the “f” bomb or “cs” references, commitment to the LGBT community is either. Karen is above that. There was a marked by her dedication to a broad spec - KV: I made friends with the legendary drag complaint once about the double enten - trum of causes and organizations. -

A Study Guide for Teachers

KAPUT A STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS ABOUT THE STUDY GUIDE Dear Teachers: We hope you will find this Study Guide helpful in preparing your students for what they will experience at the performance of Kaput. Filled with acrobatic thrills and silly blunders, we’re sure Kaput will delight you and your students. Throughout this Study Guide you will find topics for discussion, links to resources and activities to help facilitate discussion around physical theatre, physical comedy, and the golden age of silent films. STUDY GUIDE INDEX ABOUT THE PERFORMANCE RESOURCES AND TOPICS FOR DISCUSSION 1. About the Performer 1. Be the Critic 2. About the Show 2. Tell a Story Without Saying a Word 3. About Physical Theatre 3. Making a Silent Film 4. About Physical Comedy 4. Body and Expression 5. The Art of the Pratfall 5. Taking a Tour 6. The Golden Age of Silent Films (1894 – 1924) 6. Pass the Ball 7. Physical Comedy + Silent Film = Silent Comedy 7. What’s in a Gesture? Being in the Audience When you enter the theater, you enter a magical space, charged, full of energy and anticipation. Show respect by watching and listening attentively Do not distract fellow audience members or interrupt the flow of performance Applause at the end of the performance is the best way to show enthusiasm and appreciation. About The Performer Tom Flanagan is one of Australia’s youngest leading acrobatic clowns. A graduate of the internationally renowned circus school, The Flying Fruit Flies; Tom started tumbling, twisting, flying and falling at the age of six. -

Tenor F2 to C5

TALENT REPRESENTATION Miriam Chinnick [email protected] ADDRESS Davis Gordon Management 11 Eastern Avenue Pinner HA5 1NU United Kingdom TELEPHONE +44 (0) 7989 306 252 WEBSITE www.davisgordon.com HEIGHT: 5’10” EYES: Blue HAIR: Blonde- Medium TRAINING: Mountview Academy of Theatre Arts, MA Musical Theatre PLAYING AGE: 20-30 years A Cappella, Ballet, Baritone-High*, Choral Singing*, Classical Singing*, Dance (general), Falsetto*, Folk Singing, Harmonica, Jazz Dancing, Jazz Singing*, Opera, Piano, Rock Singing*, Tap, Ukulele, Violin Actor-Singer, Comedy, Comedy Improv, Compere, Master of Ceremonies, Musical Comedy, Musical Impersonator, Musical Theatre, Physical Comedy, Public Debating, Public Speaking, Singer-Professional, Stand-up Comic, Voice Acting, Voice Over Boxing, Horse-riding, Rowing*, Rugby*, Scuba Diving, Shooting (Shotgun), Skiing*, Squash, Swimming*, Trampoline Artist (Fine Art), Artist (Oils/Oil Pastels), Artist (Portrait), Bartender, Cartoonist (experienced), Cow Milking (by hand), Graphic Artist (experienced), Impersonation, Improvisation, Painting, Scenic Artist, Scientist (qualified), Video Gaming Car Driving Licence Tenor F2 to C5 American-New York, American-Southern States, American-Standard, Australian, Cockney, German, Heightened RP, Norfolk, RP*, Scottish-Standard, South African, Suffolk, West Country, Yorkshire MUSICAL TITLE ROLE DIRECTOR THEATRE/PRODUCER News Revue Cast Becky Harrison Canal Café Theatre Death Takes Are A Holiday Vittorio Lamberti Jack Sain Mountview My Favourite Year Alan Swann Suzy Catliff Mountview STAGE TITLE ROLE DIRECTOR THEATRE/PRODUCER Waiting For Godot The Boy Sean Mathias Theatre Royal Haymarket Company OTHER TITLE ROLE DIRECTOR PRODUCER British Museum Audio Guide Alex Robin Brooks / Fiona McAlpine Allegra Productions (Audio) . -

Amongst Friends: the Australian Cult Film Experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2013 Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience Renee Michelle Middlemost University of Wollongong Recommended Citation Middlemost, Renee Michelle, Amongst friends: the Australian cult film experience, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Social Sciences, Media and Communication, University of Wollongong, 2013. http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/4063 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Amongst Friends: The Australian Cult Film Experience A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY From UNIVERSITY OF WOLLONGONG By Renee Michelle MIDDLEMOST (B Arts (Honours) School of Social Sciences, Media and Communications Faculty of Law, Humanities and The Arts 2013 1 Certification I, Renee Michelle Middlemost, declare that this thesis, submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of Social Sciences, Media and Communications, University of Wollongong, is wholly my own work unless otherwise referenced or acknowledged. The document has not been submitted for qualifications at any other academic institution. Renee Middlemost December 2013 2 Table of Contents Title 1 Certification 2 Table of Contents 3 List of Special Names or Abbreviations 6 Abstract 7 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction -

GLAAD Where We Are on TV (2020-2021)

WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 Where We Are on TV 2020 – 2021 2 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 CONTENTS 4 From the office of Sarah Kate Ellis 7 Methodology 8 Executive Summary 10 Summary of Broadcast Findings 14 Summary of Cable Findings 17 Summary of Streaming Findings 20 Gender Representation 22 Race & Ethnicity 24 Representation of Black Characters 26 Representation of Latinx Characters 28 Representation of Asian-Pacific Islander Characters 30 Representation of Characters With Disabilities 32 Representation of Bisexual+ Characters 34 Representation of Transgender Characters 37 Representation in Alternative Programming 38 Representation in Spanish-Language Programming 40 Representation on Daytime, Kids and Family 41 Representation on Other SVOD Streaming Services 43 Glossary of Terms 44 About GLAAD 45 Acknowledgements 3 WHERE WE ARE ON TV 2020 – 2021 From the Office of the President & CEO, Sarah Kate Ellis For 25 years, GLAAD has tracked the presence of lesbian, of our work every day. GLAAD and Proctor & Gamble gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) characters released the results of the first LGBTQ Inclusion in on television. This year marks the sixteenth study since Advertising and Media survey last summer. Our findings expanding that focus into what is now our Where We Are prove that seeing LGBTQ characters in media drives on TV (WWATV) report. Much has changed for the LGBTQ greater acceptance of the community, respondents who community in that time, when our first edition counted only had been exposed to LGBTQ images in media within 12 series regular LGBTQ characters across both broadcast the previous three months reported significantly higher and cable, a small fraction of what that number is today. -

Would I Lie to You

Would i lie to you click here to download Would I Lie to You? is a British comedy panel show aired on BBC One, made by Zeppotron for . This list does not include the special Comic Relief episode.Episodes · Lee Mack · Henning Wehn. Comedy panel show where contestants have to bluff about their deepest secrets the opposing team have to find out which ones are true Available now · Upcoming episodes · Clips · Series 10, Episode 3. Comedy · Two teams, lead by their team leader (either Lee Mack or David Mitchell), have to try and make the other team believe their crazy stories. Rob Brydon hosts the eighth series of the comedy panel show where celebrity guests reveal amazing stories. Directed by: Olivier Boscovitch & Dominique Pochat Download / Streaming (incl Deezer, Spotify, Apple Music). Lee's "You are the best female truck driver in the world! Would I Lie to You Series 7 Episode 9 - Highlights. Adil Ray: "I once had to go all the way to Bradford just to make a phone call to prove I was in Bradford." Season. Music video by Charles & Eddie performing Would I Lie To You. As it turns 10, the BBC show is now as satisfying and reliable as Friday night fish and chips. From David Mitchell and Lee Mack's comic. Look into my eyes, can't you see they're open wide? Would I lie to you, baby, would I lie to you? Oh yeah Don't you know it's true, girl, there's no one else but you. Comedy panel show hosted by Rob Brydon, with David Mitchell and Lee Mack as team captains. -

THIS ISSUE: Comedy

2014-2015 September ISSUE 1 scene. THE JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL SCHOOLS THEATRE ASSOCIATION THIS ISSUE: Comedy www.ista.co.uk WHO’S WHO @ ISTA… CONTENTS Patron 2 Connections Professor Jonothan Neelands, by Rebecca Kohler National Teaching Fellow, Chair of Drama and Theatre Education in the Institute of Education 3 Comedy d’un jour and Chair of Creative Education in the Warwick Business School (WBS) at the University of by Francois Zanini Warwick. 4 Learning through humour Board of trustees by Mike Pasternak Iain Stirling (chair), Scotland Formerly Superintendent, Advanced Learning Schools, Riyadh. Recently retired. 8 Desperately seeking the laughs Jen Tickle (vice chair), Jamaica by Peter Michael Marino Head of Visual & Performing Arts and Theory of Knowledge at The Hillel Academy, Jamaica. 9 “Chou” – the comic actor in Chinese opera Dinos Aristidou, UK by Chris Ng Freelance writer, director, consultant. 11 Directing comedy Alan Hayes, Belgium by Sacha Kyle Theatre teacher International School Brussels. Sherri Sutton, Switzerland 12 Videotape everything, change and be Comic, director and chief examiner for IB DP Theatre. Theatre teacher at La Chataigneraie. grateful Jess Thorpe, Scotland by Dorothy Bishop Co Artistic Director of Glas(s) Performance and award winning young people’s company 13 Seriously funny Junction 25. Visiting. Lecturer in the Arts in Social Justice at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland. by Stephen Finegold Honorary life members 15 How I got the best job in the world! Dinos Aristidou, UK Being a clown, being a