The U. S. Coast Guard at Camp Lejeune, a Brief History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulletin 181101 (PDF Edition)

RAO BULLETIN 1 November 2018 PDF Edition THIS RETIREE ACTIVITIES OFFICE BULLETIN CONTAINS THE FOLLOWING ARTICLES Pg Article Subject . * DOD * . 05 == Overseas Holiday Mail ---- (2018 Deadlines) 05 == DoD MSEP ---- (VA Joins Military Spouse Employment Partnership) 06 == DoD Budget 2020 ---- (First Cut Under Trump | Limited to $700B) 07 == Iraq War [01] ---- (Unvarnished History to be Published by Xmas) 08 == DoD GPS USE Policy ---- (Deployed Servicemember Apps Restrictied) 08 == INF Russian Treaty ---- (Post-INF landscape) 10 == DoD/VA Seamless Transition [37] ---- (Cerner’s EHR Will Be Standard) 13 == Military Base Access [02] ---- (Proposal to Use for U.S. Fuel Exports to Asia) 14 == Military Base Access [03] ---- (American Bases in Japan) 15 == DoD Fraud, Waste, & Abuse ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 OCT 2018) 17 == Agent Orange Forgotten Victims [01] ---- (U.S. Prepares for Biggest-Ever Cleanup) 18 == POW/MIA Recoveries & Burials ---- (Reported 16 thru 31 OCT 2018 | 21) 1 . * VA * . 21 == VA AED Cabinets ---- (Naloxone Addition to Reverse Opioid Overdoses) 22 == VA Pension Program [02] ---- (Entitlement Regulations Amended) 22 == VA Transplant Program [04] ---- (Vet Denied Lung Transplant | Too Old) 23 == Agent Orange | C-123 Aircraft [16] ---- (Exposure Presumption Now Official) 24 == Right to Die Program ---- (Denied to Vets Residing in California Veteran Homes) 25 == VA Essential Equipment ---- (Availability Delays) 26 == VA Pension Poachers ---- (Crooked Financial Planners Target Elderly Vets) 26 == VA Claims Processing [18] ---- (Significant -

The British Commonwealth and Allied Naval Forces' Operation with the Anti

THE BRITISH COMMONWEALTH AND ALLIED NAVAL FORCES’ OPERATION WITH THE ANTI-COMMUNIST GUERRILLAS IN THE KOREAN WAR: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE OPERATION ON THE WEST COAST By INSEUNG KIM A dissertation submitted to The University of Birmingham For the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of History and Cultures College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham May 2018 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This thesis examines the British Commonwealth and Allied Naval forces operation on the west coast during the final two and a half years of the Korean War, particularly focused on their co- operation with the anti-Communist guerrillas. The purpose of this study is to present a more realistic picture of the United Nations (UN) naval forces operation in the west, which has been largely neglected, by analysing their activities in relation to the large number of irregular forces. This thesis shows that, even though it was often difficult and frustrating, working with the irregular groups was both strategically and operationally essential to the conduct of the war, and this naval-guerrilla relationship was of major importance during the latter part of the naval campaign. -

“What Are Marines For?” the United States Marine Corps

“WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2011 Major Subject: History “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era Copyright 2011 Michael Edward Krivdo “WHAT ARE MARINES FOR?” THE UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS IN THE CIVIL WAR ERA A Dissertation by MICHAEL EDWARD KRIVDO Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved by: Chair of Committee, Joseph G. Dawson, III Committee Members, R. J. Q. Adams James C. Bradford Peter J. Hugill David Vaught Head of Department, Walter L. Buenger May 2011 Major Subject: History iii ABSTRACT “What Are Marines For?” The United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. (May 2011) Michael E. Krivdo, B.A., Texas A&M University; M.A., Texas A&M University Chair of Advisory Committee: Dr. Joseph G. Dawson, III This dissertation provides analysis on several areas of study related to the history of the United States Marine Corps in the Civil War Era. One element scrutinizes the efforts of Commandant Archibald Henderson to transform the Corps into a more nimble and professional organization. Henderson's initiatives are placed within the framework of the several fundamental changes that the U.S. Navy was undergoing as it worked to experiment with, acquire, and incorporate new naval technologies into its own operational concept. -

Always a Marine” Men’S Hoodie for Me City State Zip in the Size Indicated Below As Described in This Announcement

MAGAZINE OF THE MARINES 4 1 0 2 LY U J Leathernwwew.mca-marcines.org/lekatherneck Happy Birthday, America Iraq 2004: Firefghts in the “City of Mosques” Riding With the Mounted Color Guard Settling Scores: The Battle to Take Back Guam A Publication of the Marine Corps Association & Foundation Cov1.indd 1 6/12/14 12:04 PM Welcome to Leatherneck Magazine’s Digital Edition July 2014 We hope you are continuing to enjoy the digital edition of Leatherneck with its added content and custom links to related information. Our commitment to expanding our digital offerings continues to refect progress. Also, access to added content is available via our website at www.mca- marines.org/leatherneck and you will fnd reading your Leatherneck much easier on smartphones and tablets. Our focus of effort has been on improving our offerings on the Internet, so we want to hear from you. How are we doing? Let us know at: [email protected]. Thank you for your continuing support. Semper Fidelis, Col Mary H. Reinwald, USMC (Ret) Editor How do I navigate through this digital edition? Click here. L If you need your username and password, call 1-866-622-1775. Welcome Page Single R New Style.indd 2 6/12/14 11:58 AM ALWAYS FAITHFUL. ALWAYS READY. Cov2.indd 1 6/9/14 10:31 AM JULY 2014, VOL. XCVII, No. 7 Contents LEATHERNECK—MAGAZINE OF THE MARINES FEATURES 10 The In-Between: Touring the Korean DMZ 30 100 Years Ago: Marines at Vera Cruz By Roxanne Baker By J. -

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M

North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources State Historic Preservation Office Ramona M. Bartos, Administrator Governor Roy Cooper Office of Archives and History Secretary Susi H. Hamilton Deputy Secretary Kevin Cherry August 10, 2018 Rick Richardson [email protected] Cultural Resources Program, USMC Camp Lejeune 12 Post Lane MCIEast-MCB Camp Lejeune Camp Lejeune, NC 28547 Re: Historic Resource Re-evaluation Report, Stone Bay Rifle Range Historic District, Camp Lejeune, Onslow County, ER 07-2777 Dear Mr. Richardson: Thank you for your email of July 19, 2018, transmitting the above-referenced report. We have reviewed the materials submitted regarding the Stone Bay Rifle Range Historic District (ON1030), which was determined eligible for the National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) in 2000. We concur that a boundary decrease is warranted. However, we recommend that the boundary continue to include the remaining contributing structures of the “village.” The revised south boundary would run east with Powder Lane across Rifle Range Road to the eastern district boundary as shown on the enclosed map. We concur that the district remains eligible for listing under Criterion A for military history. Furthermore, we believe the district to be eligible under Criterion C as the entirety of the complex, village and ranges, represents a “significant and distinguished entity” of military design and construction. The above comments are made pursuant to Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation’s Regulations for Compliance with Section 106 codified at 36 CFR Part 800. Thank you for your cooperation and consideration. -

2020 Corporate Membership Levels

2020 Corporate Membership Levels Educating 21St Century Leaders and Warfighters MARINE CORPS UNIVERSITY FOUNDATION Commandant’s Circle Invitation to all Foundation special Special recognition at Foundation $100,000+ events event programs, promotional materials, and other publications, Day-long Foundation Battlefield Multiple subscriptions to the including a self-designed half-page Tour and Leadership Development Foundation magazine, as desired acknowledgment in two issues of the Study, led by a Foundation Foundation magazine representative (for up to 15 guests, Recognition as Foundation including tour, deluxe shuttle bus, Corporate Member, recognized in Invitation to all Foundation special lunch and snacks) Foundation communications events The choice of five tables at the Navy Cross Circle Multiple subscriptions to the annual Foundation Semper Fidelis $50,00-$99,999 Foundation magazine, as desired Award Dinner (Washington metropolitan area) or the annual Dinner and Tour of Marine Corps Recognition as Foundation Russell Leadership Award Luncheon War Memorial (Iwo Jima Memorial), Corporate Member, recognized in (New York) led by a Foundation representative Foundation communications (for up to 6 guests) Five foursomes at the Foundation’s Silver Star Circle Semper Fidelis Golf Classic The choice of three tables at the $25,000-49,999 annual Foundation Semper Fidelis Invitation to exclusive Foundation Dinner (Washington metropolitan The choice of two tables at the receptions area) or the annual Russell annual Foundation Semper Fidelis Leadership -

Naval Juniorreserve ()Hiders

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 219 280 SE 038 787 e $ . AUTHOR ' Omans, S. E.; And Others TITLE Workbook for Naval Science 3: An Illustrated Workbook for the NJROTC Sjudent. Focus. on the Trained Person. Technical Report 124. INSTITUTION University of Central Florida, Orlando.. -, SPONS AGENCY Naval %Training Analysis and Evaluation Group, Orlando, Fla. PUB DATE May f2 GRANT N61339-79-D-0105 4 NOTE if 348p.- 4 ,EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Astronomy; Electricity; High Schools; Instructional -Materials; *Leadership; Meteotiology; Military Science; *Military Training; *Physical Sciences; ( *Remedial Reading; *Secondary School Science; Workbooks' _ IDENTIFIERS Navaleistory; *Naval JuniorReserve ()Hiders . ,-..\ Traiffing torps , '-'--..... ..,. ABSTRACT This workbook (first in a series of three) - supplements the textbook of the third year Naval Junior Reserve Officers Training Corps (NJROTC),program and is designed for NJROTC students who do not have the reading skillsOlecessary to fully benefit from the regular curriculum materidls. The workbook is written at the eighth-grade readability level as detprmined by a Computer Readability Editing System'analysis. In addition to its use in the NJROTC program, the wdrkbook may be useful in 'several remedial programs such as Academic Remedial Training(ART) and;the Verbal' Skills Curriculum,\Jzoth of which are offered at each 'of the three . RecruitTraining Com?nands to recruits deficient in reading or oral English skills.' Topics' in the workbook include naval history (1920-1945), leadership.characteristiCs, meteorology, astronomy, sand introductory electricity.'Exercises-include'vocabulary development, matching, concept application, and -extending Yearning actrties. (Author/JN) V 1' ****************************.0***,*************************************** * * Reproductions suppled'bi EDRS are the best that can be made. from- the oryiginal% document. -

A BRIEF HISTORY of the 9Th MARINES

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE 9th MARINES By Truman R. Strobridge First Printing 1961 Second Printing 1963 Revised 1967 HISTORICAL BRANCH, G-3 DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, U. S. MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON, D. C. 20380 1967 DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON D. C. 20380 PREFACE "A Brief History of the 9th Marines" is revised at this time in order to provide a concise narrative of the activity of the regiment since its activation in 1917 to its present participation in Vietnam as part of the III Marine Amphibious Force. This history is based on the official records of the United States Marine corps and appropriate secondary sources. It is published for the information of those interested in the regiment and the role it played and continues to play in adding to Marine corps traditions and battle honors. <SIGNATURE> R. L. MURRAY Major General, U. S. Marine Corps Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3 REVIEWED AND APPROVED 7 Dec 1961 DISTRIBUTION: Code DA Special Historical List 2. Special Historical List 3. A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE 9TH MARINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Original Online Page Page Brief History of the 9th Marines 1 6 Notes 22 27 Appendix A - Commanding Officers, 9th Marines, 1917-1961 25 30 Appendix B - 9th Marines Medal of Honor Recipients 29 34 Appendix C - Campaign Streamers of 9th Marines 30 35 BRIEF HISTORY OF THE 9TH MARINES By Truman R. Strobridge World War I The 9th Marines had its origin in the great expansion of the Marine Corps during World War I. Created as one of the two Infantry regiments of the Advanced Base Force, it was assigned to duty in the Carribean area as a mobile force in readiness. -

New Interpretations in Naval History Craig C

U.S. Naval War College U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons Historical Monographs Special Collections 1-1-2012 HM 20: New Interpretations in Naval History Craig C. Felker Marcus O. Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/historical-monographs Recommended Citation Felker, Craig C. and Jones, Marcus O., "HM 20: New Interpretations in Naval History" (2012). Historical Monographs. 20. https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/historical-monographs/20 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Collections at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Monographs by an authorized administrator of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NAVAL WAR COLLEGE PRESS New Interpretations in Naval History Selected Papers from the Sixteenth Naval History Symposium Held at the United States Naval Academy 10–11 September 2009 New Interpretations in Naval History Interpretations inNaval New Edited by Craig C. Felker and Marcus O. Jones O. andMarcus Felker C. Craig by Edited Edited by Craig C. Felker and Marcus O. Jones NNWC_HM20_A-WTypeRPic.inddWC_HM20_A-WTypeRPic.indd 1 22/15/2012/15/2012 33:23:40:23:40 PPMM COVER The Four Days’ Battle of 1666, by Richard Endsor. Reproduced by courtesy of Mr. Endsor and of Frank L. Fox, author of A Distant Storm: The Four Days’ Battle of 1666 (Rotherfi eld, U.K.: Press of Sail, 1996). The inset (and title-page background image) is a detail of a group photo of the midshipmen of the U.S. -

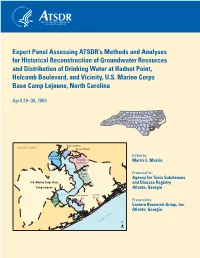

Expert Panel Assessing ATSDR's Methods and Analyses for Historical

Expert Panel Assessing ATSDR’s Methods and Analyses for Historical Reconstruction of Groundwater Resources and Distribution of Drinking Water at Hadnot Point, Holcomb Boulevard, and Vicinity, U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina April 29 –30, 2009 NORTH CAROLINA Montford Point ONSLOW COUNTY Tarawa Terrace New River Edited by: Air Station Holcomb Boulevard Morris L. Maslia New Hadnot Prepared for: Point Agency for Toxic Substances U.S. Marine Corps Base and Disease Registry Camp Lejeune Atlanta, Georgia River Courthouse Onslow Rifle Bay Beach Range Prepared by: Eastern Research Group, Inc. Atlanta, Georgia Atlantic Ocean N Cover. Location of U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and historical water-supply areas. Expert Panel Assessing ATSDR’s Methods and Analyses for Historical Reconstruction of Groundwater Resources and Distribution of Drinking Water at Hadnot Point, Holcomb Boulevard, and Vicinity, U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina April 29–30, 2009 Edited by: Morris L. Maslia Prepared for: Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry Atlanta, Georgia Prepared by: Eastern Research Group, Inc. Atlanta, Georgia Atlanta, Georgia December 2009 ii Suggested citation: Maslia ML, editor, 2009, Expert Panel Assessing ATSDR’s Methods and Analyses for Historical Reconstruction of Groundwater Resources and Distribution of Drinking Water at Hadnot Point, Holcomb Boulevard, and Vicinity, U.S. Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, April 29–30, 2009: Prepared by Eastern Research Group, Inc., -

Shipmates on Parade USS Rankin (AKA-103)

Shipmates on Parade USS Rankin (AKA-103) Table of Contents Year Rank/ Years PDF Name Born Rate Aboard Page Lawson P. "Red" Ramage .... 1909 ......CAPT ...........1953-1954 ..................... 3 Roland “Drew” Miller .......... 1922 ......LTJG(MC) .....1946-1947 ..................... 5 Elmer Mayes ........................ 1925 ......HMC ............1962-1965 ..................... 6 Fernando "Fred" Golingan .. 1925 ......SD3 .............1952-1957 ..................... 7 Paul Allen ............................ 1926 ......ENS (SC) ......1946-1947 ..................... 8 Hillyer “Billy” Head .............. 1926 ......S2C ..............1945 ............................ 13 Melvin Munch ..................... 1926 ......S1C ..............1946 ............................ 17 Tom Jones ........................... 1926 ......S1C ..............1945-1946 ................... 18 Lucien Trigiano .................... 1926 ......ENS .............1945-1946 ................... 19 Harry Berry .......................... 1928 ......EM3 ............1946-1947 ................... 21 Ed Gaskell ............................ 1928 ......LT ................1954-1956 ................... 24 Billy M. Weckwerth ............. 1928 ......MM3 ...........1946-1947 ................... 25 Dennis Heenan .................... 1929 ......LTJG ............1952-1953 ................... 27 Bob Hilley ............................ 1929 ......ENS/LTJG .....1952-1953 ................... 29 Vern Smith........................... 1929 ......ENS/LTJG .....1956-1958 ................... 31 -

Raider Patch Magazine of the Marine Raider Association No

The Raider Patch Magazine of the Marine Raider Association No. 150 1st Qtr 2021 Doc Gleason Essay Contest Winners Cognitive Raider Essay Contest Open The Story of PFC Bruno Oribiletti marineraiderassociation.org A National Non-Profit Organization Supporting: The Marine Raider Museum at Raider Hall, Quantico VA Executive Committee and Directors: President and Director 1st Vice President and Director Pending Col Neil Schuehle, USMC (Ret) MSgt Zach Peters, USMC (Ret) 2nd Vice President and Director (1st MRB, MRTC) (1st MRB) [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Secretary and Director Membership Secretary and Director Treasurer and Director LtCol Wade Priddy, USMC (Ret) MSgt Micheal Poggi, USMC (Ret) Sigrid Klock McAllister, (Hon 2BN) (Det-1) (2nd MRB, MRTC) 1855 Kanawha Trail [email protected] [email protected] Stone Mountain, GA 30087-2132 (770)-939-3692 Past President and Director [email protected] Col Craig Kozeniesky, USMC (Ret) (Det-1, MARSOC HQ) Directors: MajGen Mark Clark, USMC (Ret) MSgt John Dailey USMC (Ret) MGySgt Corey Nash, USMC (Ret) (MARSOC HQ) (Det-1, MRTC) (3MRB, MRTC, HQ) [email protected] GySgt Oscar Contreras, USMC (Ret) Col J. Darren Duke, USMC LtCol Jack O'Toole, USMC (Ret) (1st MRB, MRTC) (3rd MRB, MARSOC HQ, MRSG) (MARSOC HQ) Officers: Chaplain Legal Counsel Historical and Legacy Preservation John S. Eads IV Paul Tetzloff Bruce N. Burlingham- WWII Historian [email protected] Pete Bartle Doug Bailey Communications Committee Advisor Public Affairs Louie Marsh Membership Committee Bill EuDaly (Hon 4th Bn.) Jenny Ruffini (Hon) Emeritus Board Members: Bob Buerlein (Hon) Jim Johannes (Hon) Robert J.