Douglas Munro at Guadalcanal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2016 Newsletter

Freedom’s Voice The Monthly Newsletter of the Military History Center 112 N. Main ST Broken Arrow, OK 74012 http://www.okmhc.org/ “Promoting Patriotism through the Preservation of Military History” Volume 4, Number 8 August 2016 United States Armed Services August MHC Events Day of Observance August was a busy month for the Military History Center. Two important patriotic events were held at the Museum and a Coast Guard Birthday – August 4 fundraiser, Military Trivia Evening, was held at the Armed Forc- es Reserve Center in Broken Arrow. On Saturday, August 6, the MHC hosted Purple Heart Recognition Day. Because of a morning rainstorm, the event was held inside the Museum rather than on the Flag Plaza as planned. Even with the rain, about 125 or so local patriots at- tended the event, including a large contingent of Union High School ROTC cadets. The Ernest Childers Chapter of the Military Order of the Purple Heart presented the event. Ms. Elaine Childers, daugh- ter of Medal of Honor and Purple Heart Recipient, Lt. Col. Ern- est Childers was the special guest. The ninth annual Wagoner County Coweta Mission Civil War Weekend will be held on October 28-30 at the farm of Mr. Arthur Street, located southeast of Coweta. Mr. Street is a Civil War reenactor and an expert on Civil War Era Artillery. This is an event you won’t want to miss. So, mark your cal- endars now. The September newsletter will contain detailed information about the event. All net proceeds from the Civil War Weekend are for the benefit of the MHC. -

Inside Marine Barracks Hawaii Furls Flag After 90 Years Area Esbblished By

August 4, 1994 Vol. 22 No. 31 Serving Marine Forces Pacific, Marine Corps Base Hawaii, I sf MEB, and 1st Radio Battalion Marine Barracks Hawaii furls flag after 90 years Cpl. Bruce Drake sat Wriw While the music of the Marine Forces Pacific Band drifted across the parade deck in front of historic Puller Hall, Colonel W. W. North CH-46 celebrates its 30 officially disestablished Marine year anniversary with the Barracks Hawaii, Friday. Corpso,..See A-6 The ceremony marked not only the end of an era for Marine Bar- racks Hawaii, but the beginning of a new one as Marine Security Force Company, Pearl Harbor. Bicycle registration "This is not a sad moment or one in passing, as we are not completely If your bicycle was stolen from disestablishing the Marine presenCe your quarters or barracks, how at Pearl Harbor, but reassigning would you be able to identify it them to a new organization which to the military police? Of all will remain essential to the Navy- stolen bicycles reported to date, Marine Corps team," said Rear Adm. a disproportionate number are William Retz, commander of Naval not registered and/or secured. Base Pearl Harbor. Bicycles must be registered in "These Marines will continue the order to deter theft and locate traditions of excellence that have owners of those that are stolen. marked Marine Barracks Hawaii's The Hawaii Revised Statues service to Pearl Harbor," he added. requires all bicycles (and mopeds) Many in the crowd reflected on to be registered biannually. Each the history of the Barracks and its CO Bruce OnAs owner is furnished with a headquarters, future during thew short but sol- Final ceremony - A Marine color guard and platoon stand in front of Puller Hall, Marine Barrack Hawaii's metallic tag or decal for each emn morning ceremony. -

Gudalcanal American Memorial

ENGLISH American Battle Monuments Commission This agency of the United States government operates and AMERICAN BATTLE MONUMENTS COMMISSION maintains 26 American cemeteries and 30 memorials, monuments and markers in 17 countries. The Commission works to fulfill the vision of its first chairman, General of the Armies John J. Pershing. Guadalcanal American Memorial Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces during World War I, promised that “time will not dim the glory of their deeds.” Guadalcanal American Memorial GPS S9 26.554 E159 57.441 The Guadalcanal American Memorial stands on Skyline Ridge overlooking the town of Honiara and the Matanikau River. American Battle Monuments Commission 2300 Clarendon Boulevard Suite 500 Arlington, VA 22201 USA Guadalcanal American Manila American Cemetery Memorial McKinley Road Skyline Ridge Global City, Taguig P.O. Box 1194 Republic of Philippines Honiara, Solomon Islands tel 011-632-844-0212 email [email protected] tel 011-677-23426 gps N14 32.483 E121 03.008 For more information on this site and other ABMC commemorative sites, please visit ‘Time will not dim the glory of their deeds.’ www.abmc.gov - General of the Armies John J. Pershing January 2019 Guadalcanal American Memorial Marine artillerymen The Guadalcanal American operate from a Japanese field gun Memorial honors those emplacement captured American and Allied servicemen early in the Guadalcanal who lost their lives during the campaign. Photo: The National Archives Guadalcanal campaign of World War II. The memorial consists of AUGUST 8: Marine units occupied the Japanese airdrome at Lunga. It an inscribed central pylon four Photo: ABMC was later named Henderson Field. -

Interview with Peter Rafferty # VRV-A-L-2011-064.01 Interview # 1: December 15, 2011 Interviewer: Mark Depue

Interview with Peter Rafferty # VRV-A-L-2011-064.01 Interview # 1: December 15, 2011 Interviewer: Mark DePue COPYRIGHT The following material can be used for educational and other non-commercial purposes without the written permission of the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. “Fair use” criteria of Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976 must be followed. These materials are not to be deposited in other repositories, nor used for resale or commercial purposes without the authorization from the Audio-Visual Curator at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library, 112 N. 6th Street, Springfield, Illinois 62701. Telephone (217) 785-7955 Note to the Reader: Readers of the oral history memoir should bear in mind that this is a transcript of the spoken word, and that the interviewer, interviewee and editor sought to preserve the informal, conversational style that is inherent in such historical sources. The Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library is not responsible for the factual accuracy of the memoir, nor for the views expressed therein. We leave these for the reader to judge. DePue: Today is Thursday, December 15, 2011. My name is Mark DePue, the Director of Oral History with the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library. This morning I'm in the library, talking to Peter Rafferty. Good morning Pete. Rafferty: Good morning Mark. DePue: And you go by Pete, don't you? Rafferty: Yes I do. DePue: We are here to talk to Pete about his experiences as a Marine during the Vietnam War, during the very early stages of the Vietnam War. But, as I always do, I'd like to start off with a little bit about where and when you were born and learn a little bit about you, growing up. -

164Th Infantry News: September 1998

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons 164th Infantry Regiment Publications 9-1998 164th Infantry News: September 1998 164th Infantry Association Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation 164th Infantry Association, "164th Infantry News: September 1998" (1998). 164th Infantry Regiment Publications. 55. https://commons.und.edu/infantry-documents/55 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in 164th Infantry Regiment Publications by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE 164TH INFANTRY NEWS Vot 38 · N o, 6 Sepitemlber 1, 1998 Guadalcanal (Excerpts taken from the book Orchids In The Mud: Edited by Robert C. Muehrcke) Orch id s In The Mud, the record of the 132nd Infan try Regiment, edited by Robert C. Mueherke. GUADALCANAL AND T H E SOLOMON ISLANDS The Solomon Archipelago named after the King of Kings, lie in the Pacific Ocean between longitude 154 and 163 east, and between latitude 5 and 12 south. It is due east of Papua, New Guinea, northeast of Australia and northwest of the tri angle formed by Fiji, New Caledonia, and the New Hebrides. The Solomon Islands are a parallel chain of coral capped isles extending for 600 miles. Each row of islands is separated from the other by a wide, long passage named in World War II "The Slot." Geologically these islands are described as old coral deposits lying on an underwater mountain range, whi ch was th rust above the surface by long past volcanic actions. -

Douglas A. Munro Coast Guard Headquarters Building

113TH CONGRESS REPORT " ! 1st Session HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 113–153 DOUGLAS A. MUNRO COAST GUARD HEADQUARTERS BUILDING JULY 16, 2013.—Referred to the House Calendar and ordered to be printed Mr. SHUSTER, from the Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, submitted the following R E P O R T [To accompany H.R. 2611] [Including cost estimate of the Congressional Budget Office] The Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure, to whom was referred the bill (H.R. 2611) to designate the headquarters building of the Coast Guard on the campus located at 2701 Martin Luther King, Jr., Avenue Southeast in the District of Columbia as the ‘‘Douglas A. Munro Coast Guard Headquarters Building’’, and for other purposes, having considered the same, report favorably thereon without amendment and recommend that the bill do pass. CONTENTS Page Purpose of Legislation ............................................................................................. 2 Background and Need for Legislation .................................................................... 2 Hearings ................................................................................................................... 2 Legislative History and Consideration .................................................................. 2 Committee Votes ...................................................................................................... 2 Committee Oversight Findings ............................................................................... 3 New Budget Authority -

The 1St Marine Division and Its Regiments

thHHarine division and its regiments HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, U.S. MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON, D.C. A Huey helicopter rapidly dispatches combat-ready members of Co C, 1st Bn, 1st Mar, in the tall-grass National Forest area southwest of Quang Tri in Viet- nam in October 1967. The 1st Marine Division and Its Regiments D.TSCTGB MARINE CORPS RESEARCH CENTER ATTN COLLECTION MANAGEMENT (C40RCL) MCCDC 2040 BROADWAY ST QUANTICOVA 22134-5107 HISTORY AND MUSEUMS DIVISION HEADQUARTERS, U.S. MARINE CORPS WASHINGTON, D.C. November 1981 Table of Contents The 1st Marine Division 1 The Leaders of the Division on Guadalcanal 6 1st Division Commanding Generals 7 1st Marine Division Lineage 9 1st Marine Division Honors 11 The 1st Division Patch 12 The 1st Marines 13 Commanding Officers, 1st Marines 15 1st Marines Lineage 18 1st Marines Honors 20 The 5th Marines 21 Commanding Officers, 5th Marines 23 5th Marines Lineage 26 5th Marines Honors 28 The 7th Marines 29 Commanding Officers, 7th Marines 31 7th Marines Lineage 33 7th Marines Honors 35 The 1 1th Marines 37 Commanding Officers, 11th Marines 39 1 1th Marines Lineage 41 1 1th Marines Honors 43 iii The 1st Marine Division The iST Marine Division is the direct descendant of the Marine Corps history and its eventual composition includ- Advance Base Brigade which was activated at Philadelphia ed the 1st, 5th, and 7th Marines, all infantry regiments, on 23 December 1913. During its early years the brigade and the 11th Marines artillery regiment. Following the was deployed to troubled areas in the Caribbean. -

Additional Historic Information the Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish

USS Hornet Sea, Air & Space Museum Additional Historic Information The Doolittle Raid (Hornet CV-8) Compiled and Written by Museum Historian Bob Fish AMERICA STRIKES BACK The Doolittle Raid of April 18, 1942 was the first U.S. air raid to strike the Japanese home islands during WWII. The mission is notable in that it was the only operation in which U.S. Army Air Forces bombers were launched from an aircraft carrier into combat. The raid demonstrated how vulnerable the Japanese home islands were to air attack just four months after their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. While the damage inflicted was slight, the raid significantly boosted American morale while setting in motion a chain of Japanese military events that were disastrous for their long-term war effort. Planning & Preparation Immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack, President Roosevelt tasked senior U.S. military commanders with finding a suitable response to assuage the public outrage. Unfortunately, it turned out to be a difficult assignment. The Army Air Forces had no bases in Asia close enough to allow their bombers to attack Japan. At the same time, the Navy had no airplanes with the range and munitions capacity to do meaningful damage without risking the few ships left in the Pacific Fleet. In early January of 1942, Captain Francis Low1, a submariner on CNO Admiral Ernest King’s staff, visited Norfolk, VA to review the Navy’s newest aircraft carrier, USS Hornet CV-8. During this visit, he realized that Army medium-range bombers might be successfully launched from an aircraft carrier. -

CAMP PENDLETON HISTORY Early History Spanish Explorer Don

CAMP PENDLETON HISTORY Early History Spanish explorer Don Gasper de Portola first scouted the area where Camp Pendleton is located in 1769. He named the Santa Margarita Valley in honor of St. Margaret of Antioch, after sighting it July 20, St. Margaret's Day. The Spanish land grants, the Rancho Santa Margarita Y Las Flores Y San Onofre came in existence. Custody of these lands was originally held by the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, located southeast of Pendleton, and eventually came into the private ownership of Pio Pico and his brother Andre, in 1841. Pio Pico was a lavish entertainer and a politician who later became the last governor of Alto California. By contrast, his brother Andre, took the business of taming the new land more seriously and protecting it from the aggressive forces, namely the "Americanos." While Andre was fighting the Americans, Pio was busily engaged in entertaining guests, political maneuvering and gambling. His continual extravagances soon forced him to borrow funds from loan sharks. A dashing businesslike Englishman, John Forster, who has recently arrived in the sleepy little town of Los Angeles, entered the picture, wooing and winning the hand of Ysidora Pico, the sister of the rancho brothers. Just as the land-grubbers were about to foreclose on the ranch, young Forster stepped forward and offered to pick up the tab from Pio. He assumed the title Don Juan Forster and, as such, turned the rancho into a profitable business. When Forster died in 1882, James Flood of San Francisco purchased the rancho for $450,000. -

1 a Stamp for Gunny Minila John Basilone USMC the Gysgt John

1 A Stamp for Gunny Minila John Basilone USMC The GySgt John Basilone Award for Courage and Commitment was first presented on Basilone Day 19 February 2004, at the Freedom Museum in Manassas, Virginia to Sergeant Major C.A. “Mack” McKinney [USMC ret]. Brooks Corely, at the time National Executive Director for the Marine Corps League was asked to choose to whom the award would be presented. The award was presented by the Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps, Sergeant Major Estrada. As a tribute to Sergeant Major Estrada it was decided that hence forth the awardees would always be chosen by the Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps. The Basilone Award is only given to Non Commissioned Officers [NCOs]. The list of recipients is requested by the Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps from his Senior NCOs. The Sergeant Major of the Marine Corps then picks a recipient from the list of nominees. The Sergeant Major’s office then notifies the Basilone Award Committee and the award is designed and arrangements are made to send the award to the Marine recipient. The purpose of the GySgt John Basilone Award for Courage and Commitment is to honor the memory of GySgt John Basilone as well as to recognize the actions of today’s Marines who uphold the ultimate attributes of what it means to be a United States Marine. When the GySgt John Basilone Award for Courage and Commitment is given it is done so in the honor of all those Marines who did not get to come home. What you are about to read is an American story. -

Manila American Cemetery and Memorial

Manila American Cemetery and Memorial American Battle Monuments Commission - 1 - - 2 - - 3 - LOCATION The Manila American Cemetery is located about six miles southeast of the center of the city of Manila, Republic of the Philippines, within the limits of the former U.S. Army reservation of Fort William McKinley, now Fort Bonifacio. It can be reached most easily from the city by taxicab or other automobile via Epifanio de los Santos Avenue (Highway 54) and McKinley Road. The Nichols Field Road connects the Manila International Airport with the cemetery. HOURS The cemetery is open daily to the public from 9:00 am to 5:00 pm except December 25 and January 1. It is open on host country holidays. When the cemetery is open to the public, a staff member is on duty in the Visitors' Building to answer questions and escort relatives to grave and memorial sites. HISTORY Several months before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, a strategic policy was adopted with respect to the United States priority of effort, should it be forced into war against the Axis powers (Germany and Italy) and simultaneously find itself at war with Japan. The policy was that the stronger European enemy would be defeated first. - 4 - With the surprise Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941 and the bombing attacks on 8 December on Wake Island, Guam, Hong Kong, Singapore and the Philippine Islands, the United States found itself thrust into a global war. (History records the other attacks as occurring on 8 December because of the International Date Line. -

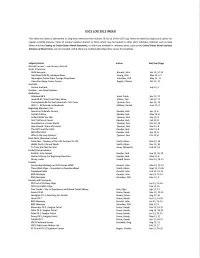

Uses L06 2012 INDEX

uses L06 2012 INDEX This Index lists items of permanent or long-term reference from Volume 79, #I-12 of the USCS Log. Items are listed by subject and author for regular monthly features. Items of merely transient interest or those which may be located in other USCS reference material, such as Data Sheets and the Catalog of United States Naval Postmarks, or which are available in reference texts, such as the United States Nuval Institute Almanuc of Naval Facts, are not included. USS & USCG are omitted with ship/cutter names for simplicity. Subject/Article Author Mo/Year/Page Aircraft Carriers -see Carriers, Aircraft Arctic / Antarctic RMS Nascopie Burnett, John Jan 12, 12-14 Northland (USCG); Hooligan News Young, John May 12, 6-7 Norwegian Cruise Ships; Foreign Navy News Schreiber, Phil May 12, 15 Operation Deep Freeze Covers Bogart, Charles Oct 12, 17 Australia Aurora Australis July 12, 5 Aviation - see Naval Aviation Battleships Alabama BB 8 Hoak, Frank Apr 12, 27 Iowa BB 61; West Coast Navy News Minter, Ted Feb 12, 11 Pennsylvania BB 38; Herb Rommel's First Cover Tjossem, Don Apr 12, 19 WW II - BB Gun Barrel Bookends Milliner, Darrell June 12, 9 Beginning Members, For American Philatelic Society Rawlins, Bob Jan 12, 8 Cachet Artistry Rawlins, Bob May 12, 8 Collect What You Like Tjossem, Don Sep 12, 8 Don't Write on Covers Rawlins, Bob Feb 12, 8 How Much is a Cover Worth Tjossem, Don Dec 12.10 How Should I Store My Covers Tjossem, Don Nov 12, 8 The USPS and the USCS Rawlins, Bob Mar 12, 8 WESTPEX 2012 Rawlins, Bob Apr 12, 8 What is the Locy System? Tjossem, Don Oct I2, 8 Book Deck; (Reviewer Listed) Fatal Dive - Mystery of the USS Grunion SS 216 Smith, Glenn Nov 12, 26 HMAS Perth, Life and Death Smith, Glenn Dec 12, 26 To Train the Fleet for War Jones, Richard D.