Mccloud Arm Watershed Analysis May 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Mt. Shasta 70305 N

C ITY OF MT . S HASTA F REEZE M INI -S TORAGE AND C AR W ASH P ROJECT REVISED AND RECIRCULATED INITIAL STUDY/ MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NO. 2017072042 Prepared for: CITY OF MT. SHASTA 70305 N. MT. SHASTA BLVD. MT. SHASTA, CA 96067 Prepared by: 2729 PROSPECT PARK DRIVE, SUITE 220 RANCHO CORDOVA, CA 95670 JUNE 2019 C ITY OF MT . S HASTA F REEZE M INI -S TORAGE AND C AR W ASH P ROJECT REVISED AND RECIRCULATED INITIAL STUDY/ MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NO. 2017072042 Prepared for: CITY OF MT. SHASTA 305 N. MT. SHASTA BLVD. MT. SHASTA, CA 96067 Prepared by: MICHAEL BAKER INTERNATIONAL 2729 PROSPECT PARK DRIVE, SUITE 220 RANCHO CORDOVA, CA 95670 JUNE 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction and Regulatory Guidance ................................................................................... 1.0-1 1.2 Lead Agency .................................................................................................................................. 1.0-1 1.3 Purpose and Document Organization ...................................................................................... 1.0-1 1.4 Evaluation of Environmental Impacts ........................................................................................ 1.0-2 2.0 PROJECT INFORMATION 3.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 3.1 Project Location ............................................................................................................................. 3.0-1 3.2 Existing Use and Conditions ........................................................................................................ -

California Fish and Game Commission 35

^^r..-^» CALIFORNIA FISH-GAME I Volume 33 STATE OF CALIFORNIA DEPARTMENT OP NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FISH AND GAME SAN FRANCISCO, CALIFORNIA EARL WARREN GOVERNOR WARREN T. HANNUM DIRECTOR OP NATURAL RESOURCES FISH AND GAME COMMISSION LEE P. PAYNE, President Los Angeles W. B. WILLIAMS, Commissioner Alturas HARVEY HASTAIN, Commissioner Brawley WILLIAM J. SILVA, Commissioner Modesto H. H. ARNOLD, Commissioner Sonoma EMIL J. N. OTT, Jr., Executive Secretary Sacramento BUREAU OF FISH CONSERVATION A. C. TAPT, Chief San Francisco A- E. BurghdufC, Supervisor of Pish Hatcheries San Prancisco L. Phillips, Assistant Supervisor of Pish Hatcheries San Prancisco George McCloud, Assistant Supervisor of Fish Hatcheries Mt. Shasta D. A. Clanton, Assistant Supervisor of Fish Hatcheries Fillmore Allan Pollitt, Assistant Supervisor of Fish Hatcheries Tahoe R. C. Lewis, Assistant Supervisor, Hot Creek Hatchery Bishop Wm. O. White, Foreman, Hot Creek Hatchery Bishop J. William Cook, Construction Foreman San Prancisco L. E. Nixon, Foreman, Yosemite Hatchery Yosemite Wm. Fiske, Foreman, Feather River Hatchery Clio Leon Talbott, Foreman, Mt. WTiitney Hatchery Independence Carleton Rogers, Foreman, Black Rock Ponds Independence A. N. Culver, Foreman, Kaweah Hatchery . Three Rivers John Marshall, Foreman, Lake Almanor Hatchery Westwood Ross McCloud, Foreman, Basin Creek Hatchery Tuolumne Harold Hewitt, Foreman, Burney Creek Hatchery Burney C. L. Frame, Foreman, Kings River Hatchery Fresno Edward Clessen, Foreman, Brookdale Hatchery Brookdale Harry Cole, Foreman, Yuba River Hatchery Camptonville Donald Bvins, Foreman, Hot Creek Hatchery Bishop Cecil Ray, Foreman, Kern Hatchery Kernville Carl Freyschlag, Foreman, Central Valley Hatchery Elk Grove S. C. Smedley, Foreman, Prairie Creek Hatchery Orick C. W. Chansler, Foreman, Fillmore Hatchery Fillmore G. -

2 Appendix C Cultural Tech Report

September 9, 2015 PACIFICORP Lassen Substation Project Cultural Resource Survey DRAFT REPORT Siskiyou County, California LEGAL DESCRIPTION: T40N, R4W, SECTIONS 9, 16, 17, AND 21 USGS QUADRANGLE: CITY OF MT. SHASTA, CA. PROJECT NUMBER: 136412 PROJECT CONTACT: Michael Dice EMAIL: [email protected] PHONE: 714-507-2700 POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey Cultural Resource Survey DRAFT REPORT PacifiCorp Lassen Substation Project Siskiyou County, California PREPARED FOR: PACIFICORP PREPARED BY: MICHAEL DICE 714-507-2700 [email protected] POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey CONFIDENTIAL This report contains information on the nature and location of prehistoric and historic cultural resources. Under California Office of Historic Preservation guidelines as well as several laws and regulations, the locations of cultural resource sites are considered confidential and cannot be released to the public. ANA 130-227 (PER 02) PACIFICORP (09/16/2015) 136412 YU PAGE i POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK ANA 130-227 (PER 02) PACIFICORP (09/16/2015) 136412 YU PAGE ii POWER ENGINEERS, INC. Lassen Substation Project – Cultural Resource Survey TABLE OF CONTENTS MANAGEMENT S UMMARY............................................................................................................ 1 1.0 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... -

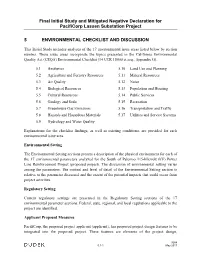

Final Initial Study and Mitigated Negative Declaration for Pacificorp Lassen Substation Project

Final Initial Study and Mitigated Negative Declaration for PacifiCorp Lassen Substation Project 5 ENVIRONMENTAL CHECKLIST AND DISCUSSION This Initial Study includes analyses of the 17 environmental issue areas listed below by section number. These issue areas incorporate the topics presented in the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) Environmental Checklist (14 CCR 15000 et seq., Appendix G). 5.1 Aesthetics 5.10 Land Use and Planning 5.2 Agriculture and Forestry Resources 5.11 Mineral Resources 5.3 Air Quality 5.12 Noise 5.4 Biological Resources 5.13 Population and Housing 5.5 Cultural Resources 5.14 Public Services 5.6 Geology and Soils 5.15 Recreation 5.7 Greenhouse Gas Emissions 5.16 Transportation and Traffic 5.8 Hazards and Hazardous Materials 5.17 Utilities and Service Systems 5.9 Hydrology and Water Quality Explanations for the checklist findings, as well as existing conditions, are provided for each environmental issue area. Environmental Setting The Environmental Setting sections present a description of the physical environment for each of the 17 environmental parameters analyzed for the South of Palermo 115-kilovolt (kV) Power Line Reinforcement Project (proposed project). The discussion of environmental setting varies among the parameters. The content and level of detail of the Environmental Setting section is relative to the parameter discussed and the extent of the potential impacts that could occur from project activities. Regulatory Setting Current regulatory settings are presented in the Regulatory Setting sections of the 17 environmental parameter sections. Federal, state, regional, and local regulations applicable to the project are identified. Applicant Proposed Measures PacifiCorp, the proposed project applicant (applicant), has proposed project design features to be integrated into the proposed project. -

Mccloud Flats Ecosystem Analysis

McCloud Flats Ecosystem Analysis September, 1995 Last Edited – February 27, 2004 Preface The work that went into this report is part of the Aquatic Conservation Strategy adopted for the President’s Plan (Record of Decision for Amendments to Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management Planning Documents within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl, including Standards and Guidelines for Management of Habitat for Late- Successional and Old Growth Related Species). Announcements were published in three local newspapers inviting public input to this analysis. An Open House was held on June 15, 1995 in McCloud, where resource specialists presented information on existing conditions and management direction for the McCloud Flats Focus Area, and the Ash Creek and Mud Creek watersheds. The McCloud Flats Interdisciplinary Team included the following resource specialists: Steve Funk, Forester and Team Leader, McCloud Ranger District Francis Mangels, Wildlife Biologist, McCloud Ranger District Dale Etter, Fuels Officer, McCloud Ranger District Steve Bachmann, Hydrologist, McCloud Ranger District Gregg DeNitto, Pathologist, Shasta-Trinity National Forest Bill Brock, Fisheries Biologist, US Fish and Wildlife Service, Weaverville Jeff Huhtala, Zone Engineering Technician Gerald Hoertling, Archaeological Technician, McCloud Ranger District Julie Cassidy, Zone Archaeologist, Mt. Shasta Ranger District Jonna Cooper, Geographic Information Systems Specialist Peter Van Susteren, Soil Scientist, McCloud Ranger District Mark Steiger, Botanist, Mycologist Annette Sun, Writer-Editor, McCloud Ranger District Watershed Analyses are iterative, or living, documents that can be updated as new information becomes available. The following edits were made on February 27, 2004: 1. The date of the last edit was inserted at bottom of the Title Page. -

City Council and Redevelopment Agency (Rda) Concurrent Regular Meeting

CITY COUNCIL AND REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY (RDA) CONCURRENT REGULAR MEETING AGENDA John Beaudet Community Center 1525 Median Avenue Shasta Lake, CA 96019 Tuesday, April 5, 2011 at 6:00 P.M. The Brown Act prohibits the Council from taking action on any item not placed on the Agenda in most cases. The Brown Act requires any non-confidential documents or writings distributed to a majority of the City Council less than 72 hours before a regular meeting to be made available to members of the public at the same time they are distributed. Should supplemental materials to be evaluated in the decision making process be made available to the members of the legislative body at the meeting, seven (7) copies must be provided to the City Clerk who will distribute them. Agenda packets are available for public review at City Hall, 1650 Stanton Drive, Shasta Lake, CA during normal business hours of 7:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m. weekdays, excluding holidays. Parties with a disability as provided by the American Disabilities Act who require special accommodations in order to participate in the public meeting should make a request to the City Clerk at least 72 hours prior to the meeting. 1.0 CITY COUNCIL/RDA MEETING – CALL TO ORDER Call to order (please place cell phones and pagers on silent. Statement for the record of Council/Board members present Pledge of Allegiance Invocation 2.0 AWARDS/RECOGNITIONS CC a) Proclamation declaring April 2011 as Child Abuse Prevention Awareness Month. Page 1 b) Proclamation declaring April 10-16, 2011 as National Library Week. -

Proudly MADE in the a Happy Little Publication November 2012 USA Some Current Events - History - Fun & Adventure in the Heart of the State of Jefferson !

FREE LOCAL INFORMATION GUIDE Proudly MADE In The A Happy Little Publication November 2012 USA Some Current Events - History - Fun & Adventure in The Heart of The State of Jefferson ! You’re in Bigfoot Country Now . Enter with Excitement !! Scan QR Code to read You can Read our Publications Online ANYTIME at our Publications each month - ONLINE !! www.JeffersonBackroads.com - Click on the Back Issues Tab Siskiyou County Chamber Alliance Collier Interpretive Links to All Chambers www.siskiyouchambers.com & Information Center Butte Valley Chamber at Junction of PO Box 541 Dorris, CA 96023 & 530-397-2111 www.buttevalleychamber.com Dunsmuir Chamber 5915 Dunsmuir Avenue Butte Valley Museum Ley Station & Museum Dunsmuir, CA 96025 Main Street SW Corner Oregon & West Miner St. 530-235-2177 Dorris, CA 96023 Yreka, CA 96097 www.dunsmuir.com (530) 397-5831 (530) 842-1649 www.buttevalleychamber.com Happy Camp Chamber Dunsmuir Railroad Depot Museum PO Box 1188 Pine Street and Sacramento Avenue Montague Depot Museum Happy Camp, CA 96039 AMTRAK Station 230 South 11th Street 530-493-2900 Dunsmuir, CA 96025 Montague, CA 96064 www.happycampchamber.org (530) 235-0929 (530) 459-3385 dunsmuir.com/visitor/railroad.php McCloud Chamber Etna Museum The People’s Center The Karuk Tribe PO Box 372 520 Main Street 64236 Second Avenue McCloud, CA 96057 Etna, CA 96027 Happy Camp, CA 96039 530-964-3113 (530) 467-5366 (530) 493-1600 www.mccloudchamber.com www.etnamuseum.org www.karuk.us Mt. Shasta Chamber Fort Jones Museum Siskiyou County Museum 300 Pine Street 11913 Main Street 910 Main Street Mt. Shasta, CA 96067 Fort Jones, CA 96032 Yreka, CA 96097 530-926-4865 (530) 468-5568 (530) 842-3836 www.mtshastachamber.com www.fortjonesmuseum.com siskiyoucountyhistoricalsociety.org Scott Valley Chamber Genealogy Society of Siskiyou Co. -

Chapter 13: History After 1849

Mount Shasta Annotated Bibliography Chapter 13 History after 1849 This section contains entries about the settlement of the Mt. Shasta region, and includes materials about pioneers, railroads, lumbering, newspapers, and other post Gold Rush activities. Most of the works cover the late 19th Century and early 20th Century. Mae Helen Bacon Boggs's My Playhouse was a Concord Coach... is the most complete available compilation of newspaper articles about a variety of topics in local history. Other historical works are comprehensive about more specific topics, for example, railroad construction and operation around Mt. Shasta are discussed in such books as John Signor's 1982 Rails In the Shadow of Shasta...(and his updated version in the year 2000 entitled :"Southern Pacific's Shasta Division: Over a Century of Railroading in the Shadow of Mt. Shasta") and Robert Hanft's Pine Across the Mountain. See also Section 1. Comprehensive Histories of Mt. Shasta for other works describing the varied activities of the settlement era. The [MS number] indicates the Mount Shasta Special Collection accession numbers used by the College of the Siskiyous Library. [MS831]. Apperson, Or. The Sisson Story. In: The Siskiyou Pioneer in Folklore, Fact and Fiction and Yearbook. Siskiyou County Historical Society. Fall, 1952. Vol. 2. No. 2. 13. History after 1849. [MS831]. [MS1017]. Apperson, Or. The Herald Celebrates Its 100th Birthday. In: Mount Shasta Herald. Mt. Shasta, Calif.: Sept. 16, 1987. Third Section. pp. 1-4. 'Mount Shasta Centennial Edition.' A detailed history of both the town and the newspaper of Mt. Shasta City. 13. History after 1849. -

Chapter 2 Watershed Heritage and Human Influences

Chapter 2 Watershed Heritage and Human Influences Chapter 2 establishes a historical context for understanding how we got to the current conditions in the watershed, as described in Chapter 3. This chapter discusses how past and present human activities and communities are tied to and have influenced or altered the resources in the watershed. 2.1 Native American Heritage and Influences This section of Chapter 2 discusses the historic Native American territories and tribes that occupied the Upper Sacramento River watershed, and how Native American activities have influenced the natural resources and landscape in the watershed. 2.1.1 Prehistory The upper Sacramento River watershed lies at the convergence of the Klamath Mountains, Cascade Range, and Great Valley physiographic provinces and is composed of several vegetation and zoological life zones (U.S. Geological Survey 2007). Prehistorically, several climate shifts created a varied landscape in the watershed. West (1989) describes a warmer and drier climate before 3,500 years before present (B.P.) creating a ―richer, more productive resource base‖ in the higher elevations above the Sacramento River Canyon (West 1989). This climate would have allowed an oak woodland forest within the canyon in a much larger area than found today (West 1989). The many rivers and creeks provided a substantial amount of water as well as many of the freshwater resources such as fish and mussels that were used by local people prehistorically. Among the major plant resources recorded in prehistoric contexts as well as in ethnographic contexts are acorns, pine nuts, bulbs and corms, a variety of seeds, and manzanita (Basgall and Hildebrandt 1989). -

A Happy Little Publication MAY 2013 Current Events - History - Business & Adventure in the Heart of the State of Jefferson ! Happy Mother’S Day

FREE LOCAL INFORMATION GUIDE A happy little publication MAY 2013 Current Events - History - Business & Adventure in The Heart of The State of Jefferson ! Happy Mother’s Day Read our Publications Online ANYTIME Every Month at www.JeffersonBackroads.com - Click on the Back Issues Tab. Siskiyou County Chamber Alliance Collier Interpretive Links to All Chambers www.siskiyouchambers.com & Information Center Butte Valley Chamber at Junction of PO Box 541 Dorris, CA 96023 & 530-397-2111 www.buttevalleychamber.com Dunsmuir Chamber 5915 Dunsmuir Avenue Butte Valley Museum Ley Station & Museum Dunsmuir, CA 96025 Main Street SW Corner Oregon & West Miner St. 530-235-2177 Dorris, CA 96023 Yreka, CA 96097 www.dunsmuir.com (530) 397-5831 (530) 842-1649 www.buttevalleychamber.com Happy Camp Chamber Dunsmuir Railroad Depot Museum PO Box 1188 Pine Street and Sacramento Avenue Montague Depot Museum Happy Camp, CA 96039 AMTRAK Station 230 South 11th Street 530-493-2900 Dunsmuir, CA 96025 Montague, CA 96064 www.happycampchamber.org (530) 235-0929 (530) 459-3385 dunsmuir.com/visitor/railroad.php McCloud Chamber Etna Museum The People’s Center The Karuk Tribe PO Box 372 520 Main Street 64236 Second Avenue McCloud, CA 96057 Etna, CA 96027 Happy Camp, CA 96039 530-964-3113 (530) 467-5366 (530) 493-1600 www.mccloudchamber.com www.etnamuseum.org www.karuk.us Mt. Shasta Chamber Fort Jones Museum Siskiyou County Museum 300 Pine Street 11913 Main Street 910 Main Street Mt. Shasta, CA 96067 Fort Jones, CA 96032 Yreka, CA 96097 530-926-4865 (530) 468-5568 (530) 842-3836 www.mtshastachamber.com www.fortjonesmuseum.com siskiyoucountyhistoricalsociety.org Scott Valley Chamber Genealogy Society of Siskiyou Co. -

8 Water Resource Element Draft

Mt. Shasta General Plan 2045 Water Resource Element 8.1 Watershed Hydrology 8.2 Groundwater 8.3 Water Quality 8.4 Wetland Management 8.5 Drought Tolerance and Water Conservation 8.6 Stormwater 8.7 Commercial Exporting 8.8 Historic and Cultural Significance of Water Contributing Authors: Derek Cheung and Frank Lyles, CivicSpark Fellows 2018-2019 8 WATER RESOURCE ELEMENT DRAFT 1 Mt. Shasta General Plan 2045 Water Resource Element Water, in its many forms, is an iconic and essential feature of the City of Mt. Shasta. Waterfalls, wetlands, the Sacramento River headwaters and its tributaries, and Lake Siskiyou provide recreation opportunities, environmental services, and beautiful noise and aesthetics for the enjoyment of residents and visitors. The economic, cultural, and environmental benefits that are sought from water resources are different for each resident and visitor but everyone understands the value of abundant, high-quality water. The future of the quality and quantity of Mt. Shasta’s water is uncertain. These resources are some of the most abundant but most vulnerable to human activity and climate change. City actions in the next 25 years will need to address increased water demand, increasingly severe rain events and flash flooding, uncertain groundwater supplies, and failing water infrastructure. The choices the City makes will not only impact the residents and visitors to the region but create positive benefits to downstream users like the City of Dunsmuir, City of Redding, and Central Valley Region. The City of Mt. Shasta is located at the headwaters of California’s largest What is a water feature? river system, the Sacramento River. -

Lower Mccloud River Watershed Analysis

Lower McCloud River Watershed Analysis Shasta-Trinity National Forest Shasta-McCloud Management Unit 3/18/98 Preface This Watershed Analysis is presented as part of the Aquatic Conservation Strategy adopted for the President’s Plan (Record of Decision for Amendments to Forest Service and Bureau of Land Management Planning Documents within the Range of the Northern Spotted Owl, including Standards and Guidelines for Management of Habitat for Late- Successional and Old-Growth Related Species (ROD)). The preparation of a Watershed Analysis for the Lower McCloud River Watershed follows direction in the Aquatic Conservation Strategy that requires watershed analysis “for roadless areas in non-Key Watersheds, and Riparian Reserves prior to determining how land management activities meet Aquatic Conservation Strategy objectives” (ROD B-20). This document follows the format provided in Part 2 of Ecosystem Analysis at the Watershed Scale: Federal Guide for Watershed Analysis - Version 2.2 (August 1995). This format consists of six steps: 1. Characterization of the watershed 2. Identification of issues and key questions 3. Description of current conditions 4. Description of reference conditions 5. Synthesis and interpretation of information 6. Recommendations This document is guided by two levels of analysis: • core topics - provide a broad, comprehensive understanding of the watershed. Core topics are provided in the Federal Guide for Watershed Analysis (8/95) to address basic ecological conditions, processes, and interactions at work in the watershed. • issues - focus the analysis on the main management questions to be addressed. Issues are those resource problems, concerns, or other factors upon which the analysis will be focused. Some of these issues prompted initiation of the analysis.