Siskiyou County Comprehensive Land & Resource Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

1 Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain

Nevada Areas of Heavy Use December 14, 2013 Trish Swain, Co-Ordinator TrailSafe Nevada 1285 Baring Blvd. Sparks, NV 89434 [email protected] Nev. Dept. of Cons. & Natural Resources | NV.gov | Governor Brian Sandoval | Nev. Maps NEVADA STATE PARKS http://parks.nv.gov/parks/parks-by-name/ Beaver Dam State Park Berlin-Ichthyosaur State Park Big Bend of the Colorado State Recreation Area Cathedral Gorge State Park Cave Lake State Park Dayton State Park Echo Canyon State Park Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Site Fort Churchill State Historic Park Kershaw-Ryan State Park Lahontan State Recreation Area Lake Tahoe Nevada State Park Sand Harbor Spooner Backcountry Cave Rock Mormon Station State Historic Park Old Las Vegas Mormon Fort State Historic Park Rye Patch State Recreation Area South Fork State Recreation Area Spring Mountain Ranch State Park Spring Valley State Park Valley of Fire State Park Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park Washoe Lake State Park Wild Horse State Recreation Area A SOURCE OF INFORMATION http://www.nvtrailmaps.com/ Great Basin Institute 16750 Mt. Rose Hwy. Reno, NV 89511 Phone: 775.674.5475 Fax: 775.674.5499 NEVADA TRAILS Top Searched Trails: Jumbo Grade Logandale Trails Hunter Lake Trail Whites Canyon route Prison Hill 1 TOURISM AND TRAVEL GUIDES – ALL ONLINE http://travelnevada.com/travel-guides/ For instance: Rides, Scenic Byways, Indian Territory, skiing, museums, Highway 50, Silver Trails, Lake Tahoe, Carson Valley, Eastern Nevada, Southern Nevada, Southeast95 Adventure, I 80 and I50 NEVADA SCENIC BYWAYS Lake -

CMS Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives in California

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives in California Serving American Indians and Alaska Natives Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) staff work with beneficiaries, health care providers, state government, CMS contractors, community groups and others to provide education and address questions in California. American Indians and Alaska Natives If you have questions about CMS programs in relation to American Indians or Alaska Natives: • email the CMS Division of Tribal Affairs at [email protected], or • contact a CMS Native American Contact (NAC). For a list of NAC and their information, visit https://go.cms.gov/NACTAGlist Why enroll in CMS programs? When you sign up for Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, or Medicare, the Indian health hospitals and clinics can bill these programs for services provided. Enrolling in these programs brings money into the health care facility, which is then used to hire more staff, pay for new equipment and building renovations, and saves Purchased and Referred Care dollars for other patients. Patients who enroll in CMS programs are not only helping themselves and others, but they’re also supporting their Indian health care hospital and clinics. Assistance in California To contact Indian Health Service in California, contact the California Area at (916) 930–3927. Find information about coverage and Indian health facilities in California. These facilities are shown on the maps in the next pages. Medicare California Department of Insurance 1 (800) 927–4357 www.insurance.ca.gov/0150-seniors/0300healthplans/ Medicaid/Children’s Health Medi-Cal 1 (916) 552–9200 www.dhcs.ca.gov/services/medi-cal Marketplace Coverage Covered California 1 (800) 300–1506 www.coveredca.com Northern Feather River Tribal Health— Oroville California 2145 5th Ave. -

Pit River and Rock Creek 2012 Summary Report

Pit River and Rock Creek 2012 summary report October 9, 2012 State of California Department of Fish and Wildlife Heritage and Wild Trout Program Prepared by Stephanie Mehalick and Cameron Zuber Introduction Rock Creek, located in northeastern California, is tributary to the Pit River approximately 3.5 miles downstream from Lake Britton (Shasta County; Figure 1). The native fish fauna of the Pit River is similar to the Sacramento River and includes rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss sp.), sculpin (Cottus spp.), hardhead (Mylopharadon conocephalus), Sacramento sucker (Catostomus occidentalis), speckled dace (Rhinichthys osculus) and Sacramento pikeminnow (Ptychocheilus grandis; Moyle 2002). In addition, the Pit River supports a wild population of non-native brown trout (Salmo trutta). It is unknown whether the ancestral origins of rainbow trout in the Pit River are redband trout (O. m. stonei) or coastal rainbow trout (O. m. irideus) and for the purposes of this report, we refer to them as rainbow trout. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife Heritage and Wild Trout Program (HWTP) has evaluated the Pit River as a candidate for Wild Trout Water designation since 2008. Wild Trout Waters are those that support self-sustaining wild trout populations, are aesthetically pleasing and environmentally productive, provide adequate catch rates in terms of numbers or size of trout, and are open to public angling (Bloom and Weaver 2008). The HWTP utilizes a phased approach to evaluate designation potential. In 2008, the HWTP conducted Phase 1 initial resource assessments in the Pit River to gather information on species composition, size class structure, habitat types, and catch rates (Weaver and Mehalick 2008). -

City of Mt. Shasta 70305 N

C ITY OF MT . S HASTA F REEZE M INI -S TORAGE AND C AR W ASH P ROJECT REVISED AND RECIRCULATED INITIAL STUDY/ MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NO. 2017072042 Prepared for: CITY OF MT. SHASTA 70305 N. MT. SHASTA BLVD. MT. SHASTA, CA 96067 Prepared by: 2729 PROSPECT PARK DRIVE, SUITE 220 RANCHO CORDOVA, CA 95670 JUNE 2019 C ITY OF MT . S HASTA F REEZE M INI -S TORAGE AND C AR W ASH P ROJECT REVISED AND RECIRCULATED INITIAL STUDY/ MITIGATED NEGATIVE DECLARATION STATE CLEARINGHOUSE NO. 2017072042 Prepared for: CITY OF MT. SHASTA 305 N. MT. SHASTA BLVD. MT. SHASTA, CA 96067 Prepared by: MICHAEL BAKER INTERNATIONAL 2729 PROSPECT PARK DRIVE, SUITE 220 RANCHO CORDOVA, CA 95670 JUNE 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Introduction and Regulatory Guidance ................................................................................... 1.0-1 1.2 Lead Agency .................................................................................................................................. 1.0-1 1.3 Purpose and Document Organization ...................................................................................... 1.0-1 1.4 Evaluation of Environmental Impacts ........................................................................................ 1.0-2 2.0 PROJECT INFORMATION 3.0 PROJECT DESCRIPTION 3.1 Project Location ............................................................................................................................. 3.0-1 3.2 Existing Use and Conditions ........................................................................................................ -

State of California, County of Siskiyou Board of Supervisors Minutes

State of California, County of Siskiyou Board of Supervisors Minutes, November 12, 2019 The Honorable Board of Supervisors of Siskiyou County, California, met in regular session this 12th day of November 2019; there being present Supervisors Lisa L. Nixon, Brandon Criss, Michael N. Kobseff, Ray A. Haupt and Ed Valenzuela, County Administrator Terry Barber, County Counsel Edward J. Kiernan, and County Clerk and ex-Officio Clerk of the Board of Supervisors Laura Bynum by Deputy County Clerk Wendy Winningham. The meeting was called to order by Chair Criss. Pursuant to AB23, the Clerk announced that the Board members receive no additional compensation for sitting as members of the Siskiyou County Flood Control and Water Conservation District. Supervisor Nixon led in the salute to the flag of the United States of America. Closed Session - Personnel pursuant to Government Code §54957, conference with legal counsel, existing litigation pursuant to Government Code §54956.9(d)(1), four cases, conference with labor negotiators pursuant to Government Code §54957.6, commenced at 8:33a.m., concluded at 9:59a.m., with no action taken. Report On Closed Session County Counsel Edward J. Kiernan announced that closed session concluded at 9:59a.m., with no reportable action taken. Invocation - Siskiyou County Sheriff Chaplain Keith Bradley provided the invocation. Consent Agenda – Approved. At Supervisor Haupt’s request, items 5C, County Administration’s letter to Union Pacific Railroad supporting the Siskiyou Trail Association designed Mossbrae Falls Access project, and item 5D, County Administration’s Rule 20A Credit Purchase agreement with the City of Weed for the transfer of $1,200,000 of 20A credits (County Allocation) from the County to the City, were pulled from the consent agenda for discussion. -

Shasta Lake Unit

Fishing The waters of Shasta Lake provide often congested on summer weekends. Packers Bay, Coee Creek excellent shing opportunities. Popular spots Antlers, and Hirz Bay are recommended alternatives during United States Department of Vicinity Map are located where the major rivers and periods of heavy use. Low water ramps are located at Agriculture Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area streams empty into the lake. Fishing is Jones Valley, Sugarloaf, and Centimudi. Additional prohibited at boat ramps. launching facilities may be available at commercial Trinity Center marinas. Fees are required at all boat launching facilities. Scale: in miles Shasta Unit 0 5 10 Campground and Camping 3 Shasta Caverns Tour The caverns began forming over 250 8GO Information Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity 12 million years ago in the massive limestone of the Gray Rocks Trinity Unit There is a broad spectrum of camping facilities, ranging Trinity Gilman Road visible from Interstate 5. Shasta Caverns are located o the National Recreation Area Lake Lakehead Fenders from the primitive to the luxurious. At the upper end of Ferry Road Shasta Caverns / O’Brien exit #695. The caverns are privately the scale, there are 9 marinas and a number of resorts owned and tours are oered year round. For schedules and oering rental cabins, motel accommodations, and RV Shasta Unit information call (530) 238-2341. I-5 parks and campgrounds with electric hook-ups, swimming 106 pools, and showers. Additional information on Forest 105 O Highway Vehicles The Chappie-Shasta O Highway Vehicle Area is located just below the west side of Shasta Dam and is Service facilities and services oered at private resorts is Shasta Lake available at the Shasta Lake Ranger Station or on the web managed by the Bureau of Land Management. -

Summer 2019, Volume 65, Number 2

The Journal of The Journal of SanSan DiegoDiego HistoryHistory The Journal of San Diego History The San Diego History Center, founded as the San Diego Historical Society in 1928, has always been the catalyst for the preservation and promotion of the history of the San Diego region. The San Diego History Center makes history interesting and fun and seeks to engage audiences of all ages in connecting the past to the present and to set the stage for where our community is headed in the future. The organization operates museums in two National Historic Districts, the San Diego History Center and Research Archives in Balboa Park, and the Junípero Serra Museum in Presidio Park. The History Center is a lifelong learning center for all members of the community, providing outstanding educational programs for schoolchildren and popular programs for families and adults. The Research Archives serves residents, scholars, students, and researchers onsite and online. With its rich historical content, archived material, and online photo gallery, the San Diego History Center’s website is used by more than 1 million visitors annually. The San Diego History Center is a Smithsonian Affiliate and one of the oldest and largest historical organizations on the West Coast. Front Cover: Illustration by contemporary artist Gene Locklear of Kumeyaay observing the settlement on Presidio Hill, c. 1770. Back Cover: View of Presidio Hill looking southwest, c. 1874 (SDHC #11675-2). Design and Layout: Allen Wynar Printing: Crest Offset Printing Copy Edits: Samantha Alberts Articles appearing in The Journal of San Diego History are abstracted and indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. -

SISKIYOU COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION STAFF REPORT July 17, 2019

SISKIYOU COUNTY PLANNING COMMISSION STAFF REPORT July 17, 2019 AGENDA ITEM NO. 1: ALTES USE PERMIT (UP1802) APPLICANT: Matt & Ruth Altes P.O. Box 1048 Mt Shasta, CA 96067 PROPERTY OWNER: Matt & Ruth Altes P.O. Box 1048 Mt Shasta, CA 96067 PROJECT SUMMARY: The proposed project consists of a use permit to establish an equestrian and event center. LOCATION: The parcel is approximately 9 acres, located at 138 Big Canyon Drive, Mt Shasta, CA 96067, Siskiyou County, California on APN 037-260-510 (Latitude 41°17'05.12"N, Longitude 122°17'52.50"W). GENERAL PLAN: Woodland Productivity ZONING: Highway Commercial (CH) EXHIBITS: A. Proposed Use Permit Findings B. Resolution PC-2019-024 B-1. Proposed Notations and Recommended Conditions of Approval C. Recirculated Draft Initial Study / Mitigated Negative Declaration D. Public Comments Altes Use Permit (UP1802) Page 1 SITE DESCRIPTION The 9-acre project site is located at 138 Big Canyon Drive. The project site is accessed via Big Canyon Drive. The project site is located in an open woodland area. Adjacent parcels are largely developed with residential and commercial uses and the property is near the intersection of Interstate 5 and Highway 89. Figure 1, Project Location PROJECT DESCRIPTION The project is a proposed use permit to bring an existing nine-acre equestrian and special event facility into compliance with County Code as well as to facilitate future development of the site. The facility is currently used for horse boarding/training, riding lessons, trail riding, and outdoor events, such as weddings, parties, and retreats. The use permit would allow these unpermitted uses to continue, as well as allow for training clinics and development of a septic system and two additional structures: 1) a multi- use building containing offices, restrooms, storage, and a caretaker’s residence and 2) a barn for storing hay, tack, and other horse-related materials. -

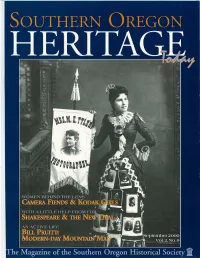

Link to Magazine Issue

----.. \\U\.1, fTI!J. Shakespeare and the New Deal by Joe Peterson ver wonder what towns all over Band, William Jennings America would have missed if it Bryan, and Billy Sunday Ehadn't been for the "make work'' was soon reduced to a projects of the New Deal? Everything from walled shell. art and research to highways, dams, parks, While some town and nature trails were a product of the boosters saw the The caved-in roofof the Chautauqua building led to the massive government effort during the decapitated building as a domes' removal, andprompted Angus Bowmer to see 1930s to get Americans back to work. In promising site for a sports possibilities in the resulting space for an Elizabethan stage. Southern Oregon, add to the list the stadium, college professor Oregon Shakespeare Festival, which got its Angus Bowmer and start sixty-five years ago this past July. friends had a different vision. They "giveth and taketh away," for Shakespeare While the festival's history is well known, noticed a peculiar similarity to England's play revenues ended up covering the Globe Theatre, and quickly latched on to boxing-match losses! the idea of doing Shakespeare's plays inside A week later the Ashland Daily Tidings the now roofless Chautauqua walls. reported the results: "The Shakespearean An Elizabethan stage would be needed Festival earned $271, more than any other for the proposed "First Annual local attraction, the fights only netting Shakespearean Festival," and once again $194.40 and costing $206.81."4 unemployed Ashland men would be put to By the time of the second annual work by a New Deal program, this time Shakespeare Festival, Bowmer had cut it building the stage for the city under the loose from the city's Fourth ofJuly auspices of the WPA.2 Ten men originally celebration. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

Payment of Taxes As a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: a Nineteenth Century Anachronism Averill Q

Santa Clara Law Review Volume 9 | Number 1 Article 13 1-1-1969 Payment of Taxes as a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: A Nineteenth Century Anachronism Averill Q. Mix Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Averill Q. Mix, Comment, Payment of Taxes as a Condition of Title by Adverse Possession: A Nineteenth Century Anachronism, 9 Santa Clara Lawyer 244 (1969). Available at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/lawreview/vol9/iss1/13 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Santa Clara Law Review by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS PAYMENT OF TAXES AS A CONDITION OF TITLE BY ADVERSE POSSESSION: A NINETEENTH CENTURY ANACHRONISM In California the basic statute governing the obtaining of title to land by adverse possession is section 325 of the Code of Civil Procedure.' This statute places California with the small minority of states that unconditionally require payment of taxes as a pre- requisite to obtaining such title. The logic of this requirement has been under continual attack almost from its inception.2 Some of its defenders state, however, that it serves to give the true owner notice of an attempt to claim his land adversely.' Superficially, the law in California today appears to be well settled, but litigation in which the tax payment requirement is a prominent issue continues to arise.