List of Articles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire*

STRUGGLE FOR EAST-EUROPEAN EMPIRE: 1400-1700 The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire* HALİL İNALCIK The empire of the Golden Horde, built by Batu, son of Djodji and the grand son of Genghis Khan, around 1240, was an empire which united the whole East-Europe under its domination. The Golden Horde empire comprised ali of the remnants of the earlier nomadic peoples of Turkic language in the steppe area which were then known under the common name of Tatar within this new political framework. The Golden Horde ruled directly över the Eurasian steppe from Khwarezm to the Danube and över the Russian principalities in the forest zone indirectly as tribute-paying states. Already in the second half of the 13th century the western part of the steppe from the Don river to the Danube tended to become a separate political entity under the powerful emir Noghay. In the second half of the 14th century rival branches of the Djodjid dynasty, each supported by a group of the dissident clans, started a long struggle for the Ulugh-Yurd, the core of the empire in the lower itil (Volga) river, and for the title of Ulugh Khan which meant the supreme ruler of the empire. Toktamish Khan restored, for a short period, the unity of the empire. When defeated by Tamerlane, his sons and dependent clans resumed the struggle for the Ulugh-Khan-ship in the westem steppe area. During ali this period, the Crimean peninsula, separated from the steppe by a narrow isthmus, became a refuge area for the defeated in the steppe. -

Uralilaisuutta Teoiksi. Kai Donner Poliittisena

Olavi Louheranta SIPERIAA SANOIKSI – URALILAISUUTTA TEOIKSI Kai Donner poliittisena organisaattorina sekä tiedemiehenä antropologian näkökulmasta Research Series in Anthropology University of Helsinki Academic dissertation Research Series in Anthropology University of Helsinki, Finland Distributed by: Helsinki University Press PO Box 4 (Vuorikatu 3 A) 00014 University of Helsinki Finland Fax: + 358-9-70102374 www.yliopistopaino.helsinki.fi Copyright © 2006 Olavi Louheranta ISSN 1458-3186 ISBN 952-10-3528-5 (nid.) ISBN 952-10-3529-3 (PDF) Helsinki University Printing House Helsinki 2006 ESIPUHE Mikä yhdistää tutkijan tutkimuskohteeseensa? Pohdittuaan kysymystä vuo- sien ajan tutkimuskohteensa näkökulmasta ajautuu väistämättä tilantee- seen, jossa saman kysymyksen joutuu kysymään myös itseltään. Vastausta ei ole helppo antaa muutaman rivin mittaisessa esipuheessa. Kiinnostus Siperiaa ja laajemmin ottaen Venäjää kohtaan nousee omasta elämänhisto- riastani. Kasvaminen toisen polven emigranttiperheessä synnytti halun muodostaa suhteen kadonneisiin ihmisiin ja paikkoihin. Siperiaan liitetyt entiteetit yksinäisyys, etäisyys ja kylmyys koetaan ja määritellään usein negatiivisesti ja ulkosyntyisesti – ne voivat kuitenkin olla positiivisia ja sisäsyntyisiä tekijöitä, merkkejä suhteessa olosta sekä rajoista. Päästäkseen lähelle on matkustettava kauas, ja kaikkein pisimmät matkat tehdäänkin usein ihmisen mielessä. Työni pariin minut johdatti professori Juha Pentikäinen tarjotessaan seminaarissa aiheeksi Kai Donnerin tutkijakuvan selvittämistä. Hän -

My Birthplace

My birthplace Ягодарова Ангелина Николаевна My birthplace My birthplace Mari El The flag • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno- Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva, Komis (Zyrians) ,Karelians ,Komi-Permians ,Maris (Cheremises), Mordvinians (Erzas and Mokshas), Udmurts (Votiaks) ,Vepsians ,Mansis (Voguls) ,Saamis (Lapps), Khanti. Mari people speak a language of the Finno-Ugric family and live mainly in Mari El, Russia, in the middle Volga River valley. • http://aboutmari.com/wiki/Этнографические_группы • http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b9NpQZZGuPI&feature=r elated • The rich history of Mari land has united people of different nationalities and religions. At this moment more than 50 ethnicities are represented in Mari El republic, including, except the most numerous Russians and Мari,Tatarians,Chuvashes, Udmurts, Mordva Ukranians and many others. Compare numbers • Finnish : Mari • 1-yksi ikte • 2-kaksi koktit • 3- kolme kumit • 4 -neljä nilit • 5 -viisi vizit • 6 -kuusi kudit • 7-seitsemän shimit • 8- kahdeksan kandashe • the Mari language and culture are taught. Lake Sea Eye The colour of the water is emerald due to the water plants • We live in Mari El. Mari people belong to Finno-Ugric group which includes Hungarian, Estonians, Finns, Hanty, Mansi, Mordva. • We have our language. We speak it, study at school, sing our tuneful songs and listen to them on the radio . Mari people are very poetic. Tourism Mari El is one of the more ecologically pure areas of the European part of Russia with numerous lakes, rivers, and forests. As a result, it is a popular destination for tourists looking to enjoy nature. -

Prior Linguistic Knowledge Matters : the Use of the Partitive Case In

B 111 OULU 2013 B 111 UNIVERSITY OF OULU P.O.B. 7500 FI-90014 UNIVERSITY OF OULU FINLAND ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS ACTA SERIES EDITORS HUMANIORAB Marianne Spoelman ASCIENTIAE RERUM NATURALIUM Marianne Spoelman Senior Assistant Jorma Arhippainen PRIOR LINGUISTIC BHUMANIORA KNOWLEDGE MATTERS University Lecturer Santeri Palviainen CTECHNICA THE USE OF THE PARTITIVE CASE IN FINNISH Docent Hannu Heusala LEARNER LANGUAGE DMEDICA Professor Olli Vuolteenaho ESCIENTIAE RERUM SOCIALIUM University Lecturer Hannu Heikkinen FSCRIPTA ACADEMICA Director Sinikka Eskelinen GOECONOMICA Professor Jari Juga EDITOR IN CHIEF Professor Olli Vuolteenaho PUBLICATIONS EDITOR Publications Editor Kirsti Nurkkala UNIVERSITY OF OULU GRADUATE SCHOOL; UNIVERSITY OF OULU, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, FINNISH LANGUAGE ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Print) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) ACTA UNIVERSITATIS OULUENSIS B Humaniora 111 MARIANNE SPOELMAN PRIOR LINGUISTIC KNOWLEDGE MATTERS The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language Academic dissertation to be presented with the assent of the Doctoral Training Committee of Human Sciences of the University of Oulu for public defence in Keckmaninsali (Auditorium HU106), Linnanmaa, on 24 May 2013, at 12 noon UNIVERSITY OF OULU, OULU 2013 Copyright © 2013 Acta Univ. Oul. B 111, 2013 Supervised by Docent Jarmo H. Jantunen Professor Helena Sulkala Reviewed by Professor Tuomas Huumo Associate Professor Scott Jarvis Opponent Associate Professor Scott Jarvis ISBN 978-952-62-0113-9 (Paperback) ISBN 978-952-62-0114-6 (PDF) ISSN 0355-3205 (Printed) ISSN 1796-2218 (Online) Cover Design Raimo Ahonen JUVENES PRINT TAMPERE 2013 Spoelman, Marianne, Prior linguistic knowledge matters: The use of the partitive case in Finnish learner language University of Oulu Graduate School; University of Oulu, Faculty of Humanities, Finnish Language, P.O. -

Transparency in Language a Typological Study

Transparency in language A typological study Published by LOT phone: +31 30 253 6111 Trans 10 3512 JK Utrecht e-mail: [email protected] The Netherlands http://www.lotschool.nl Cover illustration © 2011: Sanne Leufkens – image from the performance ‘Celebration’ ISBN: 978-94-6093-162-8 NUR 616 Copyright © 2015: Sterre Leufkens. All rights reserved. Transparency in language A typological study ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit van Amsterdam op gezag van de Rector Magnificus prof. dr. D.C. van den Boom ten overstaan van een door het college voor promoties ingestelde commissie, in het openbaar te verdedigen in de Agnietenkapel op vrijdag 23 januari 2015, te 10.00 uur door Sterre Cécile Leufkens geboren te Delft Promotiecommissie Promotor: Prof. dr. P.C. Hengeveld Copromotor: Dr. N.S.H. Smith Overige leden: Prof. dr. E.O. Aboh Dr. J. Audring Prof. dr. Ö. Dahl Prof. dr. M.E. Keizer Prof. dr. F.P. Weerman Faculteit der Geesteswetenschappen i Acknowledgments When I speak about my PhD project, it appears to cover a time-span of four years, in which I performed a number of actions that resulted in this book. In fact, the limits of the project are not so clear. It started when I first heard about linguistics, and it will end when we all stop thinking about transparency, which hopefully will not be the case any time soon. Moreover, even though I might have spent most time and effort to ‘complete’ this project, it is definitely not just my work. Many people have contributed directly or indirectly, by thinking about transparency, or thinking about me. -

Research Article Special Issue

Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences Research Article ISSN 1112-9867 Special Issue Available online at http://www.jfas.info MEANS OF EXPRESSION OF INCENTIVE MODALITY IN TATAR AND ENGLISH LANGUAGES N. Khabirova1, G. Abrosimova1,*, K. M. Minullin1, I. Khanipova1, R. R. Khairutdinov1, G. Ibragimov2 1Kazan (Volga Region) Federal University, Kazan, Russia 2Institute of Language, Literature and Art of Tatarstan Academy of Sciences Published online: 24 November 2017 ABSTRACT The relevance of the investigated problem is caused by the need to improve the functional approach to understanding the nature of the content incentive modality. The aim of the study is to identify the means of expression incentive modality in the Tatar and Russian languages, their similarities and differences. The leading approach to the study of the problems is selected descriptive-comparative method with its components - observation, comparison and generalization. The findings suggest that, in both languages there are corresponding counterparts, causing typological commonality; the most frequent way of expressing incentive modality in the English language are modal verbs and modal words, in Tatar - modal words as part of a complex predicate, the use of which depends on the context. Article Submissions may be useful in lecture courses on linguistics, in special courses on the problems of modality, as well as in the practice of teaching the Tatar and English languages. Keywords: language, translation, bilingual, incentive modality, means of expression, typological intention. Author Correspondence, e-mail: [email protected] doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/jfas.v9i7s.108 Journal of Fundamental and Applied Sciences is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License. -

Religion, Power and Nationhood in Sovereign Bashkortostan

Religion, State & Society, Vo!. 25, No. 3, 1997 Religion, Power and Nationhood in Sovereign Bashkortostan SERGEI FILATOV Relations between the nation-state and religion are always paradoxical, an effort to square the circle. Spiritual life, the search for the absolute and worship belong to a sphere which is by nature free and not susceptible to control by authority. How can a president, a police officer or an ordinary patriot decide for an individual what consti tutes truth, goodness or personal salvation from sin and death? On the other hand, faith forms the national character, moral norms and the concept of duty, and so a sense of national identity and social order depend upon it. Understanding this, states and national leaders throughout human history have used God for the benefit of Caesar. Even priests themselves often forget whom it is they serve. In all historical circumstances, however, religious faith shows that it stands outside state, nation and society, and consistently betrays the plans and expectations of monarchs, presidents, secret police, collaborators and patriots. It changes regardless of any orders from those in authority. Peoples, states, empires and civilisations change fundamentally or vanish completely because the basic ideas which supported them also vanish. Sometimes it is the rulers themselves, striving to preserve their kingdoms, who are unaware that their faith and view of the world are changing and themselves turn out to be the medium of the changes which destroy them. In the countries of the former USSR, indeed in all the former socialist camp, constant attempts to 'tame the spirit' were in themselves nothing new, but the histor ical situation, the level of public awareness and the character of religiosity were unique; and the use of religion for national and state purposes therefore acquired distinctive and somewhat grotesque characteristics. -

Transitivity in Eastern Mansi an Information Structural Approach

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Helsingin yliopiston digitaalinen arkisto Susanna Virtanen Transitivity in Eastern Mansi An Information Structural Approach Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed by due permission of the Faculty of Arts at the University of Helsinki in Auditorium XII, Main Building, on 14th of March, 2015 at 10 o’clock. 1 © Susanna Virtanen ISBN 978-951-51-0547-9 (nid.) ISBN 978-951-51-0548-6 (PDF) Printed by Painotalo Casper Oy Espoo 2015 2 Abstract This academic dissertation consists of four articles published in peer-reviewed linguistic journals and an introduction. The aim of the study is to provide a description of the formal means of expressing semantic transitivity in the Eastern dialects of the Mansi language, as well as the variation between the different means. Two of the four articles are about the marking of direct objects (DOs) in Eastern Mansi (EM), one outlines the function of noun marking in the DO marking system and one concerns the variation between three-participant constructions. The study is connected to Uralic studies and functional-linguistic typology. Mansi is a Uralic language spoken is Western Siberia. Unfortunately, its Eastern dialects died out some decades ago, but there are still approximately 2700 speakers of Northern Mansi. Because it is no longer possible to access any live data on EM, the study is based on written folkloric materials gathered by Artturi Kannisto about 100 years ago. From the typological point of view, Mansi is an agglutinative language with many inflectional and derivational suffixes. -

Governance on Russia's Early-Modern Frontier

ABSOLUTISM AND EMPIRE: GOVERNANCE ON RUSSIA’S EARLY-MODERN FRONTIER DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Paul Romaniello, B. A., M. A. The Ohio State University 2003 Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Eve Levin, Advisor Dr. Geoffrey Parker Advisor Dr. David Hoffmann Department of History Dr. Nicholas Breyfogle ABSTRACT The conquest of the Khanate of Kazan’ was a pivotal event in the development of Muscovy. Moscow gained possession over a previously independent political entity with a multiethnic and multiconfessional populace. The Muscovite political system adapted to the unique circumstances of its expanding frontier and prepared for the continuing expansion to its east through Siberia and to the south down to the Caspian port city of Astrakhan. Muscovy’s government attempted to incorporate quickly its new land and peoples within the preexisting structures of the state. Though Muscovy had been multiethnic from its origins, the Middle Volga Region introduced a sizeable Muslim population for the first time, an event of great import following the Muslim conquest of Constantinople in the previous century. Kazan’s social composition paralleled Moscow’s; the city and its environs contained elites, peasants, and slaves. While the Muslim elite quickly converted to Russian Orthodoxy to preserve their social status, much of the local population did not, leaving Moscow’s frontier populated with animists and Muslims, who had stronger cultural connections to their nomadic neighbors than their Orthodox rulers. The state had two major goals for the Middle Volga Region. -

Linguistic Variation and Minor Languages Corpora: a Case Study of Mansi Dialects1

LINGUISTIC VARIATION AND MINOR LANGUAGES CORPORA: A CASE STUDY OF MANSI DIALECTS1 Zhornik D. O. ([email protected]), Moscow State Lomonosov University, Moscow, Russia Sizov F. O. ([email protected]), Institute of Linguistics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia Annotation: This paper presents a multidialectal corpus of the Mansi language and introduces our methods of solving the problem of dialectal variation. Mansi (< Ob-Ugric < Finno-Ugric < Uralic) is a relatively poorly documented language. So far, there is not a single tolerable resource which would contain annotated texts in various Mansi dialects. Our corpus is an attempt at creating such a resource. The data to be found in the corpus are diverse both regarding the dialect they belong to and the time when they were recorded. Texts in extinct Mansi dialects (Southern, Eastern, Western) may date as far back as the 1840s, while Upper Lozva texts and audio recordings were gathered in 2017-2018. Because of this diversity, the problem of linguistic variation and its support in the corpus is crucial for us. The data which exhibit both linguistic variation and heterogeneity of writing systems need to be processed uniformly. The complex task of variation processing is solved separately at each step of corpus building: optical character recognition (OCR) during preliminary processing of printed materials, morphological annotation and search implementation based on the Tsakorpus platform. Keywords: corpus linguistics, language documentation, minor languages, Finno-Ugric languages, morphological analyzer, computational linguistics ЯЗЫКОВАЯ ВАРИАТИВНОСТЬ И КОРПУСА МАЛЫХ ЯЗЫКОВ: ИССЛЕДОВАНИЕ МАНСИЙСКИХ ДИАЛЕКТОВ Жорник Д. О. ([email protected]), Московский государственный университет имени М. -

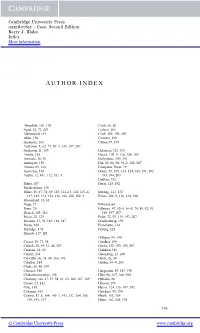

Author Index

Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. Blake Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Abondolo, 101, 105 Cook, 66, 80 Agud, 32, 72, 207 Corbett, 104 Aikhenvald, 191 Croft, 192, 193, 207 Allen, 150 Crowley, 100 Andersen, 163 Cutler, 99, 190 Anderson, J., 62, 71, 80–3, 135, 197, 207 Anderson, S., 109 Delancey, 123, 192 Anttila, 165 Dench, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Aristotle, 18, 30 Derbyshire, 100, 191 Armagost, 156 Dik, 62, 66, 68, 91–2, 188, 207 Artawa, 89, 124 Dionysius Thrax, 19 Austerlitz, 165 Dixon, 56, 105, 114, 124, 185, 191, 192, Austin, 12, 101, 112, 182–3 193, 194, 207 DuBois, 192 Baker, 187 Durie, 124, 192 Balakrishnan, 158 Blake, 15, 67, 78, 89, 107, 114–15, 124, 127–8, Ebeling, 121, 152 137, 143, 151, 154, 158, 186, 188, 192–3 Evans, 108–9, 116, 154, 190 Bloomfield, 13, 63 Bopp, 37 Filliozat, 64 Bowe, 26 Fillmore, 47, 62–3, 66–8, 74, 80, 82, 91, Branch, 105, 116 188, 197, 207 Breen, 28, 125 Foley, 72, 92, 110, 192, 207 Bresnan, 47, 92, 185, 186, 187 Frachtenberg, 190 Bryan, 102 Franchetto, 124 Burridge, 174 Friberg, 123 Burrow, 117, 181 Gilligan, 99, 190 Caesar, 19, 73, 98 Giridhar, 100 Calboli, 18, 19, 31, 48, 207 Giv´on, 112, 192, 193, 207 Cardona, 64, 65 Goddard, 186 Carroll, 138 Greenberg, 15, 160 Carvalho, de, 31, 40, 186, 192 Groot, de, 30 Catullus, 184 Gruber, 67–9, 205 Chafe, 66, 80, 207 Chaucer, 148 Haegeman, 59, 187, 190 Chidambaranathan, 158 Hale, 96, 107, 168, 194 Chomsky, xiii, 47, 57, 58, 61, 62, 186, 187, 189 Halliday, 66 Cicero, 23, 112 Hansen, 193 Cole, 110 Harris, 124, 126, 147, 192 Coleman, 105 Hawkins, 99, 190 Comrie, 87–8, 104, 140–1, 142, 152, 154, 185, Heath, 155, 159 190, 191, 207 Heine, 162, 165, 193 219 © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521807611 - Case, Second Edition Barry J. -

Spatial Semantics, Case and Relator Nouns in Evenki

Spatial semantics, case and relator nouns in Evenki Lenore A. Grenoble University of Chicago Evenki, a Northwest Tungusic language, exhibits an extensive system of nominal cases, deictic terms, and relator nouns, used to signal complex spatial relations. The paper describes the use and distribution of the spatial cases which signal stative and dynamic relations, with special attention to their semantics within a framework using fundamental Gestalt concepts such as Figure and Ground, and how they are used in combination with deictics and nouns to signal specific spatial semantics. Possible paths of grammaticalization including case stacking, or Suffixaufnahme, are dis- cussed. Keywords: spatial cases, case morphology, relator noun, deixis, Suf- fixaufnahme, grammaticalization 1. Introduction Case morphology and relator nouns are extensively used in the marking of spa- tial relations in Evenki, a Tungusic language spoken in Siberia by an estimated 4802 people (All-Russian Census 2010). A close analysis of the use of spatial cases in Evenki provides strong evidence for the development of complex case morphemes from adpositions. Descriptions of Evenki generally claim the exist- ence of 11–15 cases, depending on the dialect. The standard language is based on the Poligus dialect of the Podkamennaya Tunguska subgroup, from the Southern dialect group, now moribund. Because it forms the basis of the stand- ard (or literary) language and as such has been relatively well-studied and is somewhat codified, it usually serves as the point of departure in linguistic de- scriptions of Evenki. However, the written language is to a large degree an artifi- cial construct which has never achieved usage in everyday conversation: it does not function as a norm which cuts across dialects.