Islam: State and Religion in Modern Europe by Patrick Franke

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire*

STRUGGLE FOR EAST-EUROPEAN EMPIRE: 1400-1700 The Crimean Khanate, Ottomans and the Rise of the Russian Empire* HALİL İNALCIK The empire of the Golden Horde, built by Batu, son of Djodji and the grand son of Genghis Khan, around 1240, was an empire which united the whole East-Europe under its domination. The Golden Horde empire comprised ali of the remnants of the earlier nomadic peoples of Turkic language in the steppe area which were then known under the common name of Tatar within this new political framework. The Golden Horde ruled directly över the Eurasian steppe from Khwarezm to the Danube and över the Russian principalities in the forest zone indirectly as tribute-paying states. Already in the second half of the 13th century the western part of the steppe from the Don river to the Danube tended to become a separate political entity under the powerful emir Noghay. In the second half of the 14th century rival branches of the Djodjid dynasty, each supported by a group of the dissident clans, started a long struggle for the Ulugh-Yurd, the core of the empire in the lower itil (Volga) river, and for the title of Ulugh Khan which meant the supreme ruler of the empire. Toktamish Khan restored, for a short period, the unity of the empire. When defeated by Tamerlane, his sons and dependent clans resumed the struggle for the Ulugh-Khan-ship in the westem steppe area. During ali this period, the Crimean peninsula, separated from the steppe by a narrow isthmus, became a refuge area for the defeated in the steppe. -

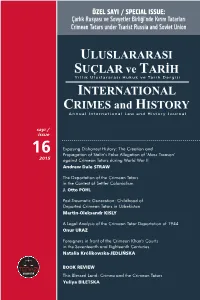

Ust Dergi Sayi 16 Layout 1

ÖZEL SAYI / SPECIAL ISSUE: Çarlık Rusyası ve Sovyetler Birliği’nde Kırım Tatarları Crimean Tatars under Tsarist Russia and Soviet Union ULUSLARARASI SUÇLAR ve TARİH Yıllık Uluslararası Hukuk ve Tarih Dergisi INTERNATIONAL CRIMES and HISTORY Annual International Law and History Journal sayı / issue 16 Exposing Dishonest History: The Creation and Propagation of Stalin’s False Allegation of ‘Mass Treason’ 2015 against Crimean Tatars during World War II Andrew Dale STRAW The Deportation of the Crimean Tatars in the Context of Settler Colonialism J. Otto POHL Post-Traumatic Generation: Childhood of Deported Crimean Tatars in Uzbekistan Martin-Oleksandr KISLY A Legal Analysis of the Crimean Tatar Deportation of 1944 Onur URAZ Foreigners in front of the Crimean Khan's Courts in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries Natalia Królikowska-JEDLIŃSKA BOOK REVIEW This Blessed Land: Crimea and the Crimean Tatars Yuliya BILETSKA ULUSLARARASI SUÇLAR VE TARİH INTERNATIONAL CRIMES AND HISTORY Yıllık Uluslararası Hakemli Dergi Annual International Peer-Reviewed Journal 2015, Sayı / Issue: 16 ISSN: 1306-9136 EDİTÖR / EDITOR E. Büyükelçi - Ambassador (R) Ömer Engin LÜTEM SORUMLU YAZI İŞLERİ MÜDÜRÜ / MANAGING EDITOR Dr. Turgut Kerem TUNCEL İMTİYAZ SAHİBİ / LICENSEE AVRASYA BİR VAKFI (1993) Bu yayın, Avrasya Bir Vakfı adına, Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi tarafından hazırlanmaktadır. This publication is edited by Center for Eurasian Studies on behalf of Avrasya Bir Vakfı. YAYIN KURULU / EDITORIAL BOARD Alfabetik Sıra ile / In Alphabetic Order Prof. Dr. Dursun Ali AKBULUT E. Büyükelçi / Ambassador (R) Alev KILIÇ (Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi) (Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi Başkanı) Prof. Dr. Ayşegül AYDINGÜN E. Büyükelçi / Ambassador (R) Ömer Engin LÜTEM (Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi) (Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi Onursal Başkanı) Prof. -

Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov Selected Works of Chokan Valikhanov

SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV CHOKAN OF WORKS SELECTED SELECTED WORKS OF CHOKAN VALIKHANOV Pioneering Ethnographer and Historian of the Great Steppe When Chokan Valikhanov died of tuberculosis in 1865, aged only 29, the Russian academician Nikolai Veselovsky described his short life as ‘a meteor flashing across the field of oriental studies’. Set against his remarkable output of official reports, articles and research into the history, culture and ethnology of Central Asia, and more important, his Kazakh people, it remains an entirely appropriate accolade. Born in 1835 into a wealthy and powerful Kazakh clan, he was one of the first ‘people of the steppe’ to receive a Russian education and military training. Soon after graduating from Siberian Cadet Corps at Omsk, he was taking part in reconnaissance missions deep into regions of Central Asia that had seldom been visited by outsiders. His famous mission to Kashgar in Chinese Turkestan, which began in June 1858 and lasted for more than a year, saw him in disguise as a Tashkent mer- chant, risking his life to gather vital information not just on current events, but also on the ethnic make-up, geography, flora and fauna of this unknown region. Journeys to Kuldzha, to Issyk-Kol and to other remote and unmapped places quickly established his reputation, even though he al- ways remained inorodets – an outsider to the Russian establishment. Nonetheless, he was elected to membership of the Imperial Russian Geographical Society and spent time in St Petersburg, where he was given a private audience by the Tsar. Wherever he went he made his mark, striking up strong and lasting friendships with the likes of the great Russian explorer and geographer Pyotr Petrovich Semyonov-Tian-Shansky and the writer Fyodor Dostoyevsky. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/99q9f2k0 Author Bailony, Reem Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Reem Bailony 2015 © Copyright by Reem Bailony 2015 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Transnational Rebellion: The Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927 by Reem Bailony Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2015 Professor James L. Gelvin, Chair This dissertation explores the transnational dimensions of the Syrian Revolt of 1925-1927. By including the activities of Syrian migrants in Egypt, Europe and the Americas, this study moves away from state-centric histories of the anti-French rebellion. Though they lived far away from the battlefields of Syria and Lebanon, migrants championed, contested, debated, and imagined the rebellion from all corners of the mahjar (or diaspora). Skeptics and supporters organized petition campaigns, solicited financial aid for rebels and civilians alike, and partook in various meetings and conferences abroad. Syrians abroad also clandestinely coordinated with rebel leaders for the transfer of weapons and funds, as well as offered strategic advice based on the political climates in Paris and Geneva. Moreover, key émigré figures played a significant role in defining the revolt, determining its goals, and formulating its program. By situating the revolt in the broader internationalism of the 1920s, this study brings to life the hitherto neglected role migrants played in bridging the local and global, the national and international. -

The Making of a Leftist Milieu: Anti-Colonialism, Anti-Fascism, and the Political Engagement of Intellectuals in Mandate Lebanon, 1920- 1948

THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In the field of History Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2017 1 THE MAKING OF A LEFTIST MILIEU: ANTI-COLONIALISM, ANTI-FASCISM, AND THE POLITICAL ENGAGEMENT OF INTELLECTUALS IN MANDATE LEBANON, 1920- 1948. A dissertation presented By Sana Tannoury Karam ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the College of Social Sciences and Humanities of Northeastern University December 2017 2 This dissertation is an intellectual and cultural history of an invisible generation of leftists that were active in Lebanon, and more generally in the Levant, between the years 1920 and 1948. It chronicles the foundation and development of this intellectual milieu within the political Left, and how intellectuals interpreted leftist principles and struggled to maintain a fluid, ideologically non-rigid space, in which they incorporated an array of ideas and affinities, and formulated their own distinct worldviews. More broadly, this study is concerned with how intellectuals in the post-World War One period engaged with the political sphere and negotiated their presence within new structures of power. It explains the social, political, as well as personal contexts that prompted intellectuals embrace certain ideas. Using periodicals, personal papers, memoirs, and collections of primary material produced by this milieu, this dissertation argues that leftist intellectuals pushed to politicize the role and figure of the ‘intellectual’. -

The Crimean Tatars and Their Russian-Captive Slaves an Aspect of Muscovite-Crimean Relations in the 16Th and 17Th Centuries

The Crimean Tatars and their Russian-Captive Slaves An Aspect of Muscovite-Crimean Relations in the 16th and 17th Centuries Eizo MATSUKI The Law Code of Tsar Aleksei Mikhailovich (Ulozhenie), being formed of 25 chapters and divided into 976 articles, is the last and the most systematic codification of Muscovite Law in early modern Russia. It was compiled in 1649, that is more than one and a half centuries after Russia’s political “Independence” from Mongol-Tatar Rule. Chapter VIII of this Law Code, comprised of 7 articles and titled “The Redemption of Military Captives”, however, reveals that Muscovite Russia at the mid-17th century was yet suffering from frequent Tatar raids into its populated territory. The raids were to capture Russian people and sell them as slaves. Because of this situation, the Muscovite government was forced to create a special annual tax (poronianichnyi zbor) to prepare a financial fund needed for ransoming Russian captive-slaves from the Tatars.1 Chapter VIII, article 1 imposes an annual levy on the common people of all Russia: 8 dengi per household for town people as well as church peasants; 4 dengi for other peasants; and 2 dengi for lower service men. On the other hand, articles 2-7 of this chapter established norms for ransom-payment to the Tatars according to the rank of the Russian captives: for gentry (dvoriane) and lesser gentry (deti boiarskie) twenty rubles per 100 chetvert’ of their service land-estate (pomest’e); for lesser ranks such as Musketeers (strel’tsy),2 Cossacks, townspeople, and peasants a fixed payment from ten to forty rubles each. -

Religion, Power and Nationhood in Sovereign Bashkortostan

Religion, State & Society, Vo!. 25, No. 3, 1997 Religion, Power and Nationhood in Sovereign Bashkortostan SERGEI FILATOV Relations between the nation-state and religion are always paradoxical, an effort to square the circle. Spiritual life, the search for the absolute and worship belong to a sphere which is by nature free and not susceptible to control by authority. How can a president, a police officer or an ordinary patriot decide for an individual what consti tutes truth, goodness or personal salvation from sin and death? On the other hand, faith forms the national character, moral norms and the concept of duty, and so a sense of national identity and social order depend upon it. Understanding this, states and national leaders throughout human history have used God for the benefit of Caesar. Even priests themselves often forget whom it is they serve. In all historical circumstances, however, religious faith shows that it stands outside state, nation and society, and consistently betrays the plans and expectations of monarchs, presidents, secret police, collaborators and patriots. It changes regardless of any orders from those in authority. Peoples, states, empires and civilisations change fundamentally or vanish completely because the basic ideas which supported them also vanish. Sometimes it is the rulers themselves, striving to preserve their kingdoms, who are unaware that their faith and view of the world are changing and themselves turn out to be the medium of the changes which destroy them. In the countries of the former USSR, indeed in all the former socialist camp, constant attempts to 'tame the spirit' were in themselves nothing new, but the histor ical situation, the level of public awareness and the character of religiosity were unique; and the use of religion for national and state purposes therefore acquired distinctive and somewhat grotesque characteristics. -

GENS VLACHORUM in HISTORIA SERBORUMQUE SLAVORUM (Vlachs in the History of the Serbs and Slavs)

ПЕТАР Б. БОГУНОВИЋ УДК 94(497.11) Нови Сад Оригиналан научни рад Република Србија Примљен: 21.01.2018 Одобрен: 23.02.2018 Страна: 577-600 GENS VLACHORUM IN HISTORIA SERBORUMQUE SLAVORUM (Vlachs in the History of the Serbs and Slavs) Part 1 Summary: This article deals with the issue of the term Vlach, that is, its genesis, dis- persion through history and geographical distribution. Also, the article tries to throw a little more light on this notion, through a multidisciplinary view on the part of the population that has been named Vlachs in the past or present. The goal is to create an image of what they really are, and what they have never been, through a specific chronological historical overview of data related to the Vlachs. Thus, it allows the reader to understand, through the facts presented here, the misconceptions that are related to this term in the historiographic literature. Key words: Vlachs, Morlachs, Serbs, Slavs, Wallachia, Moldavia, Romanian Orthodox Church The terms »Vlach«1, or later, »Morlach«2, does not represent the nationality, that is, they have never represented it throughout the history, because both of this terms exclusively refer to the members of Serbian nation, in the Serbian ethnic area. –––––––––––– [email protected] 1 Serbian (Cyrillic script): влах. »Now in answer to all these frivolous assertions, it is sufficient to observe, that our Morlacchi are called Vlassi, that is, noble or potent, for the same reason that the body of the nation is called Slavi, which means glorious; that the word Vlah has nothing -

Muslim Fertility , Religion and Religiousness

1 02/21/07 Fertility and Religiousness Among European Muslims Charles F. Westoff and Tomas Frejka There seems to be a popular belief that Muslim fertility in Europe is much higher than that of non-Muslims. Part of this belief stems from the general impression of high fertility in some Muslim countries in the Middle East, Asia and Africa. This notion is typically transferred to Muslims living in Europe with their increasing migration along with concerns about numbers and assimilability into European society. I The first part of this paper addresses the question of how much difference there is between Muslim and non-Muslim fertility in Europe (in those countries where such information is available). At the beginning of the 21 st century, there are estimated to be approximately 40 – 50 million Muslims in Europe. Almost all of the Muslims in Central and Eastern Europe live in the Balkans. (Kosovo, although formally part of Serbia, is listed as a country in Table 1). In Western Europe the majority of Muslims immigrated after the Second World War. The post-war economic reconstruction and boom required considerably more labor than was domestically available. There were two principal types of immigration to Western Europe: (a) from countries of the respective former colonial empires; and (b) from Southern Europe, the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Turkey. As much of this immigration took place during the 1950s and 1960s large proportions of present-day Muslims are second and third generation descendants. Immigrants to France came mostly from the former North African colonies Algeria (± 35 percent), Morocco (25 percent) and Tunisia (10 percent), and also from Turkey (10 percent). -

New Reality and Nagorno-Karabakh: the Cemre That Fell to Nagorno-Karabakh

Tarih İncelemeleri Dergisi XXXVI / 1, 2021, 209-251 DOI: 10.18513/egetid.974614 THE WAR BETWEEN PERIOD AND EXCLAMATION MARK: NEW REALITY AND NAGORNO-KARABAKH: THE CEMRE THAT FELL TO NAGORNO-KARABAKH * ** Vefa KURBAN - Oğuzhan ERGÜN Abstract Having always been competition fields thanks to their geopolitical impact potential, the Caucasus and Turkestan have been among the Strategic Focus Centres of Russia since the Tsarist times. While Russia, whose strategic culture has produced expansionist policies for centuries, constantly expanded its political borders, it clashed with the Ottoman Empire and Iran in the Caucasus field of competition. From the second half of the 19th century, the Kazakh regions and independent Turkic states (Khiva, Kokand and Bukhara) were occupied by the Tsarist Russia. The Imperial Age was also a period in which Russia expanded its sphere of influence over the Ottoman Empire through its patronage policies. Having embraced “New Reality” in the regional power projection in the near past, Turkey stayed away from the region for a long time. In addition to some ethnic and cultural problems paused by the Cold War, problems in the partition of the territory came to light again following the end of the Cold War and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the Caucasus geography, from south to north, went back into the period when various national issues were at the forefront and conflicts were experienced. The occupation Armenia carried out with the sponsorship and de facto military support of Russia violated the sovereignty rights of Azerbaijan, caused great social and economic harm, deteriorated the geopolitical impact potential of Azerbaijan and Turkey, and annihilated the possibility of direct connection between Turkey and Turkestan. -

Governance on Russia's Early-Modern Frontier

ABSOLUTISM AND EMPIRE: GOVERNANCE ON RUSSIA’S EARLY-MODERN FRONTIER DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Matthew Paul Romaniello, B. A., M. A. The Ohio State University 2003 Examination Committee: Approved by Dr. Eve Levin, Advisor Dr. Geoffrey Parker Advisor Dr. David Hoffmann Department of History Dr. Nicholas Breyfogle ABSTRACT The conquest of the Khanate of Kazan’ was a pivotal event in the development of Muscovy. Moscow gained possession over a previously independent political entity with a multiethnic and multiconfessional populace. The Muscovite political system adapted to the unique circumstances of its expanding frontier and prepared for the continuing expansion to its east through Siberia and to the south down to the Caspian port city of Astrakhan. Muscovy’s government attempted to incorporate quickly its new land and peoples within the preexisting structures of the state. Though Muscovy had been multiethnic from its origins, the Middle Volga Region introduced a sizeable Muslim population for the first time, an event of great import following the Muslim conquest of Constantinople in the previous century. Kazan’s social composition paralleled Moscow’s; the city and its environs contained elites, peasants, and slaves. While the Muslim elite quickly converted to Russian Orthodoxy to preserve their social status, much of the local population did not, leaving Moscow’s frontier populated with animists and Muslims, who had stronger cultural connections to their nomadic neighbors than their Orthodox rulers. The state had two major goals for the Middle Volga Region. -

The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4

The Northern Black Sea Region by Kerstin Susanne Jobst In historical studies, the Black Sea region is viewed as a separate historical region which has been shaped in particular by vast migration and acculturation processes. Another prominent feature of the region's history is the great diversity of religions and cultures which existed there up to the 20th century. The region is understood as a complex interwoven entity. This article focuses on the northern Black Sea region, which in the present day is primarily inhabited by Slavic people. Most of this region currently belongs to Ukraine, which has been an independent state since 1991. It consists primarily of the former imperial Russian administrative province of Novorossiia (not including Bessarabia, which for a time was administered as part of Novorossiia) and the Crimean Peninsula, including the adjoining areas to the north. The article also discusses how the region, which has been inhabited by Scythians, Sarmatians, Greeks, Romans, Goths, Huns, Khazars, Italians, Tatars, East Slavs and others, fitted into broader geographical and political contexts. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2. Space of Myths and Legends 3. The Northern Black Sea Region in Classical Antiquity 4. From the Khazar Empire to the Crimean Khanate and the Ottomans 5. Russian Rule: The Region as Novorossiia 6. World War, Revolutions and Soviet Rule 7. From the Second World War until the End of the Soviet Union 8. Summary and Future Perspective 9. Appendix 1. Sources 2. Literature 3. Notes Indices Citation Introduction