Emergence of Hinduism in Gandhāra an Analysis of Material Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“The Role of Specific Grammar for Interpretation in Sanskrit”

Quest Journals Journal of Research in Humanities and Social Science Volume 9 ~ Issue 2 (2021)pp: 107-187 ISSN(Online):2321-9467 www.questjournals.org Research Paper “The Role of Specific Grammar for Interpretation in Sanskrit” Dr. Shibashis Chakraborty Sact-I Depatment of Sanskrit, Panskura Banamali College Wb, India. Abstract: Sanskrit enjoys a place of pride among Indian languages in terms of technology solutions that are available for it within India and abroad. The Indian government through its various agencies has been heavily funding other Indian languages for technology development but the funding for Sanskrit has been slow for a variety of reasons. Despite that, the work in the field has not suffered. The following sections do a survey of the language technology R&D in Sanskrit and other Indian languages. The word `Sanskrit’ means “prepared, pure, refined or prefect”. It was not for nothing that it was called the `devavani’ (language of the Gods). It has an outstanding place in our culture and indeed was recognized as a language of rare sublimity by the whole world. Sanskrit was the language of our philosophers, our scientists, our mathematicians, our poets and playwrights, our grammarians, our jurists, etc. In grammar, Panini and Patanjali (authors of Ashtadhyayi and the Mahabhashya) have no equals in the world; in astronomy and mathematics the works of Aryabhatta, Brahmagupta and Bhaskar opened up new frontiers for mankind, as did the works of Charak and Sushrut in medicine. In philosophy Gautam (founder of the Nyaya system), Ashvaghosha (author of Buddha Charita), Kapila (founder of the Sankhya system), Shankaracharya, Brihaspati, etc., present the widest range of philosophical systems the world has ever seen, from deeply religious to strongly atheistic. -

Ganesha Chaturthi Hhonoringonoring Thethe Lordlord Ofof Bbeginningseginnings

www.dinodia.com Ganesha Chaturthi HHonoringonoring thethe LordLord ofof BBeginningseginnings uring Ganesha Chaturthi, a ten-day festival in clay image of Ganesha that the family makes or obtains. At August/September, elaborate puja ceremonies are the end of ten days, Hindus join in a grand parade, called Dheld in Hindu temples around the world honoring visarjana in Sanskrit, to a river, temple tank, lake or sea- Ganesha, the benevolent, elephant-faced Lord of Obstacles. shore, where His image is ceremonially immersed, sym- In millions of home shrines, worship is also offered to a bolizing Ganesha’s merging into universal consciousness. Who is Ganesha? Perennially happy, playful, unperturbed and wise, this rotund Deity removes obstacles to good endeav- ors and obstructs negative ventures, thus guiding and protecting the lives of devotees. He is the patron of art and science, the God inhabiting all entryways, the gatekeeper who blesses all beginnings. When initiat- ing anything—whether learning, business, weddings, travel, building and more—Hindus seek His grace for success. He is undoubtedly the most endearing, pop- ular and widely worshiped of all the Hindu Deities. Ganesha Chaturthi (also called Vinayaka Chaturthi) falls on the fourth day in the waxing fortnight of the month of Bhadrapada in the sacred Hindu lunar calendar, which translates to a certain day in August- September. It is essentially a birthday celebrating Ga- nesha’s divine appearance. What do people do on Ganesha Chaturthi? Devotees often fashion or purchase a Ganesha statue out of unbaked clay. Many sculpt Him out of a special mixture of turmeric, sandalwood paste, cow dung, ??????????a soumya sitaraman soumya soil from an anthill and palm sugar. -

The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga

Orissa Review * October - 2004 The Lion : Mount of Goddess Durga Pradeep Kumar Gan Shaktism, the cult of Mother Goddess and vast mass of Indian population, Goddess Durga Shakti, the female divinity in Indian religion gradually became the supreme object of 5 symbolises form, energy or manifestation of adoration among the followers of Shaktism. the human spirit in all its rich and exuberant Studies on various aspects of her character in variety. Shakti, in scientific terms energy or our mythology, religion, etc., grew in bulk and power, is the one without which no leaf can her visual representation is well depicted in stir in the world, no work can be done without our art and sculpture. It is interesting to note 1 it. The Goddess has been worshipped in India that the very origin of her such incarnation (as from prehistoric times, for strong evidence of Durga) is mainly due to her celestial mount a cult of the mother has been unearthed at the (vehicle or vahana) lion. This lion is usually pre-vedic civilization of the Indus valley. assorted with her in our literature, art sculpture, 2 According to John Marshall Shakti Cult in etc. But it is unfortunate that in our earlier works India was originated out of the Mother Goddess the lion could not get his rightful place as he and was closely associated with the cult of deserved. Siva. Saivism and Shaktism were the official In the Hindu Pantheon all the deities are religions of the Indus people who practised associated in mythology and art with an animal various facets of Tantra. -

Who Are the Buddhist Deities?

Who are the Buddhist Deities? Bodhisatta, receiving Milk Porridge from Sujata Introduction: Some Buddhist Vipassana practitioners in their discussion frown upon others who worship Buddhist Deities 1 or practice Samadha (concentrationmeditation), arguing that Deities could not help an individual to gain liberation. It is well known facts, that some Buddhists have been worshipping Deities, since the time of king Anawratha, for a better mundane life and at the same time practicing Samadha and Vipassana Bhavana. Worshipping Deities will gain mundane benefits thus enable them to do Dana, Sila and Bhavana. Every New Year Burmese Buddhists welcome the Sakka’s (The Hindu Indra God) visit from the abode of thirty three Gods - heaven to celebrate their new year. In the beginning, just prior to Gotama Buddha attains the enlightenment, many across the land practice animism – worship spirits. The story of Sujata depicts that practice. Let me present the story of Sujata as written in Pali canon : - In the village of Senani, the girl, Sujata made her wish to the tree spirit that should she have a good marriage and a first born son, she vowed to make yearly offering to the tree spirits in grateful gratitude. Her wish having been fulfilled, she used to make an offering every year at the banyan tree. On the day of her offering to the tree spirit, coincidentally, Buddha appeared at the same Banyan tree. On the full moon day of the month Vesakha, the Future Buddha was sitting under the banyan tree. Sujata caught sight of the Future Buddha and, assuming him to be the tree-spirit, offered him milk-porridge in a golden bowl. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Essays and Addresses on the Śākta Tantra-Śāstra

ŚAKTI AND ŚĀKTA ESSAYS AND ADDRESSES ON THE ŚĀKTA TANTRAŚĀSTRA BY SIR JOHN WOODROFFE THIRD EDITION REVISED AND ENLARGED Celephaïs Press Ulthar - Sarkomand - Inquanok – Leeds 2009 First published London: Luzac & co., 1918. Second edition, revised and englarged, London: Luzac and Madras: Ganesh & co., 1919. Third edition, further revised and enlarged, Ganesh / Luzac, 1929; many reprints. This electronic edition issued by Celephaïs Press, somewhere beyond the Tanarian Hills, and mani(n)fested in the waking world in Leeds, England in the year 2009 of the common error. This work is in the public domain. Release 0.95—06.02.2009 May need furthur proof reading. Please report errors to [email protected] citing release number or revision date. PREFACE TO THIRD EDITION. HIS edition has been revised and corrected throughout, T and additions have been made to some of the original Chapters. Appendix I of the last edition has been made a new Chapter (VII) in the book, and the former Appendix II has now been attached to Chapter IV. The book has moreover been very considerably enlarged by the addition of eleven new Chapters. New also are the Appendices. The first contains two lectures given by me in French, in 1917, before the Societé Artistique et Literaire Francaise de Calcutta, of which Society Lady Woodroffe was one of the Founders and President. The second represents the sub- stance (published in the French Journal “Le Lotus bleu”) of two lectures I gave in Paris, in the year 1921, before the French Theosophical Society (October 5) and at the Musée Guimet (October 6) at the instance of L’Association Fran- caise des amis de L’Orient. -

Cult Statue of a Goddess

On July 31, 2007, the Italian Ministry of Culture and the Getty Trust reached an agreement to return forty objects from the Museum’s antiq uities collection to Italy. Among these is the Cult Statue of a Goddess. This agreement was formally signed in Rome on September 25, 2007. Under the terms of the agreement, the statue will remain on view at the Getty Villa until the end of 2010. Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at The Getty Villa May 9, 2007 i © 2007 The J. Paul Getty Trust Published on www.getty.edu in 2007 by The J. Paul Getty Museum Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Los Angeles, California 900491682 www.getty.edu Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief Benedicte Gilman, Editor Diane Franco, Typography ISBN 9780892369287 This publication may be downloaded and printed in its entirety. It may be reproduced, and copies distributed, for noncommercial, educational purposes only. Please properly attribute the material to its respective authors. For any other uses, please refer to the J. Paul Getty Trust’s Terms of Use. ii Cult Statue of a Goddess Summary of Proceedings from a Workshop Held at the Getty Villa, May 9, 2007 Schedule of Proceedings iii Introduction, Michael Brand 1 Acrolithic and Pseudoacrolithic Sculpture in Archaic and Classical Greece and the Provenance of the Getty Goddess Clemente Marconi 4 Observations on the Cult Statue Malcolm Bell, III 14 Petrographic and Micropalaeontological Data in Support of a Sicilian Origin for the Statue of Aphrodite Rosario Alaimo, Renato Giarrusso, Giuseppe Montana, and Patrick Quinn 23 Soil Residues Survey for the Getty Acrolithic Cult Statue of a Goddess John Twilley 29 Preliminary Pollen Analysis of a Soil Associated with the Cult Statue of a Goddess Pamela I. -

South-Indian Images of Gods and Goddesses

ASIA II MB- • ! 00/ CORNELL UNIVERSITY* LIBRARY Date Due >Sf{JviVre > -&h—2 RftPP )9 -Af v^r- tjy J A j£ **'lr *7 i !! in ^_ fc-£r Pg&diJBii'* Cornell University Library NB 1001.K92 South-indian images of gods and goddesse 3 1924 022 943 447 AGENTS FOR THE SALE OF MADRAS GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS. IN INDIA. A. G. Barraud & Co. (Late A. J. Combridge & Co.)> Madras. R. Cambrav & Co., Calcutta. E. M. Gopalakrishna Kone, Pudumantapam, Madura. Higginbothams (Ltd.), Mount Road, Madras. V. Kalyanarama Iyer & Co., Esplanade, Madras. G. C. Loganatham Brothers, Madras. S. Murthv & Co., Madras. G. A. Natesan & Co., Madras. The Superintendent, Nazair Kanun Hind Press, Allahabad. P. R. Rama Iyer & Co., Madras. D. B. Taraporevala Sons & Co., Bombay. Thacker & Co. (Ltd.), Bombay. Thacker, Spink & Co., Calcutta. S. Vas & Co., Madras. S.P.C.K. Press, Madras. IN THE UNITED KINGDOM. B. H. Blackwell, 50 and 51, Broad Street, Oxford. Constable & Co., 10, Orange Street, Leicester Square, London, W.C. Deighton, Bell & Co. (Ltd.), Cambridge. \ T. Fisher Unwin (Ltd.), j, Adelphi Terrace, London, W.C. Grindlay & Co., 54, Parliament Street, London, S.W. Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. (Ltd.), 68—74, iCarter Lane, London, E.C. and 25, Museum Street, London, W.C. Henry S. King & Co., 65, Cornhill, London, E.C. X P. S. King & Son, 2 and 4, Great Smith Street, Westminster, London, S.W.- Luzac & Co., 46, Great Russell Street, London, W.C. B. Quaritch, 11, Grafton Street, New Bond Street, London, W. W. Thacker & Co.^f*Cre<d Lane, London, E.O? *' Oliver and Boyd, Tweeddale Court, Edinburgh. -

Ancient Universities in India

Ancient Universities in India Ancient alanda University Nalanda is an ancient center of higher learning in Bihar, India from 427 to 1197. Nalanda was established in the 5th century AD in Bihar, India. Founded in 427 in northeastern India, not far from what is today the southern border of Nepal, it survived until 1197. It was devoted to Buddhist studies, but it also trained students in fine arts, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, politics and the art of war. The center had eight separate compounds, 10 temples, meditation halls, classrooms, lakes and parks. It had a nine-story library where monks meticulously copied books and documents so that individual scholars could have their own collections. It had dormitories for students, perhaps a first for an educational institution, housing 10,000 students in the university’s heyday and providing accommodations for 2,000 professors. Nalanda University attracted pupils and scholars from Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, Indonesia, Persia and Turkey. A half hour bus ride from Rajgir is Nalanda, the site of the world's first University. Although the site was a pilgrimage destination from the 1st Century A.D., it has a link with the Buddha as he often came here and two of his chief disciples, Sariputra and Moggallana, came from this area. The large stupa is known as Sariputra's Stupa, marking the spot not only where his relics are entombed, but where he was supposedly born. The site has a number of small monasteries where the monks lived and studied and many of them were rebuilt over the centuries. We were told that one of the cells belonged to Naropa, who was instrumental in bringing Buddism to Tibet, along with such Nalanda luminaries as Shantirakshita and Padmasambhava. -

Summer/June 2014

AMORDAD – SHEHREVER- MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. 28, No 2 SUMMER/JUNE 2014 ● SUMMER/JUNE 2014 Tir–Amordad–ShehreverJOUR 1383 AY (Fasli) • Behman–Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin 1384 (Shenshai) •N Spendarmad 1383 AY Fravardin–ArdibeheshtAL 1384 AY (Kadimi) Zoroastrians of Central Asia PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Copyright ©2014 Federation of Zoroastrian Associations of North America • • With 'Best Compfiments from rrhe Incorporated fJTustees of the Zoroastrian Charity :Funds of :J{ongl(pnffi Canton & Macao • • PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF NORTH AMERICA Vol 28 No 2 June / Summer 2014, Tabestan 1383 AY 3752 Z 92 Zoroastrianism and 90 The Death of Iranian Religions in Yazdegerd III at Merv Ancient Armenia 15 Was Central Asia the Ancient Home of 74 Letters from Sogdian the Aryan Nation & Zoroastrians at the Zoroastrian Religion ? Eastern Crosssroads 02 Editorials 42 Some Reflections on Furniture Of Sogdians And Zoroastrianism in Sogdiana Other Central Asians In 11 FEZANA AGM 2014 - Seattle and Bactria China 13 Zoroastrians of Central 49 Understanding Central 78 Kazakhstan Interfaith Asia Genesis of This Issue Asian Zoroastrianism Activities: Zoroastrian Through Sogdian Art Forms 22 Evidence from Archeology Participation and Art 55 Iranian Themes in the 80 Balkh: The Holy Land Afrasyab Paintings in the 31 Parthian Zoroastrians at Hall of Ambassadors 87 Is There A Zoroastrian Nisa Revival In Present Day 61 The Zoroastrain Bone Tajikistan? 34 "Zoroastrian Traces" In Boxes of Chorasmia and Two Ancient Sites In Sogdiana 98 Treasures of the Silk Road Bactria And Sogdiana: Takhti Sangin And Sarazm 66 Zoroastrian Funerary 102 Personal Profile Beliefs And Practices As Shown On The Tomb 104 Books and Arts Editor in Chief: Dolly Dastoor, editor(@)fezana.org AMORDAD SHEHREVER MEHER 1383 AY (SHENSHAI) FEZANA JOURNAL FEZANA Technical Assistant: Coomi Gazdar TABESTAN 1383 AY 3752 Z VOL. -

ESSENCE of VAMANA PURANA Composed, Condensed And

ESSENCE OF VAMANA PURANA Composed, Condensed and Interpreted By V.D.N. Rao, Former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Union Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India 1 ESSENCE OF VAMANA PURANA CONTENTS PAGE Invocation 3 Kapaali atones at Vaaranaasi for Brahma’s Pancha Mukha Hatya 3 Sati Devi’s self-sacrifice and destruction of Daksha Yagna (Nakshatras and Raashis in terms of Shiva’s body included) 4 Shiva Lingodbhava (Origin of Shiva Linga) and worship 6 Nara Narayana and Prahlada 7 Dharmopadesha to Daitya Sukeshi, his reformation, Surya’s action and reaction 9 Vishnu Puja on Shukla Ekadashi and Vishnu Panjara Stotra 14 Origin of Kurukshetra, King Kuru and Mahatmya of the Kshetra 15 Bali’s victory of Trilokas, Vamana’s Avatara and Bali’s charity of Three Feet (Stutis by Kashyapa, Aditi and Brahma & Virat Purusha Varnana) 17 Parvati’s weds Shiva, Devi Kaali transformed as Gauri & birth of Ganesha 24 Katyayani destroys Chanda-Munda, Raktabeeja and Shumbha-Nikumbha 28 Kartikeya’s birth and his killings of Taraka, Mahisha and Baanaasuras 30 Kedara Kshetra, Murasura Vadha, Shivaabhisheka and Oneness with Vishnu (Upadesha of Dwadasha Narayana Mantra included) 33 Andhakaasura’s obsession with Parvati and Prahlaad’s ‘Dharma Bodha’ 36 ‘Shivaaya Vishnu Rupaaya, Shiva Rupaaya Vishnavey’ 39 Andhakaasura’s extermination by Maha Deva and origin of Ashta Bhairavaas (Andhaka’s eulogies to Shiva and Gauri included) 40 Bhakta Prahlada’s Tirtha Yatras and legends related to the Tirthas 42 -Dundhu Daitya and Trivikrama -

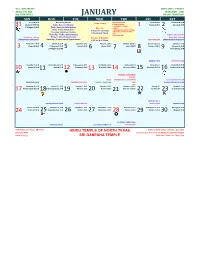

Temple Calendar

Year : SHAARVARI MARGASIRA - PUSHYA Ayana: UTTARA MARGAZHI - THAI Rtu: HEMANTHA JANUARY DHANU - MAKARAM SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT Tritiya 8.54 D Recurring Events Special Events Tritiya 9.40 N Chaturthi 8.52 N Temple Hours Chaturthi 6.55 ND Daily: Ganesha Homam 01 NEW YEAR DAY Pushya 8.45 D Aslesha 8.47 D 31 12 HANUMAN JAYANTHI 1 2 P Phalguni 1.48 D Daily: Ganesha Abhishekam Mon - Fri 13 BHOGI Daily: Shiva Abhishekam 14 MAKARA SANKRANTHI/PONGAL 9:30 am to 12:30 pm Tuesday: Hanuman Chalisa 14 MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN 5:30 pm to 8:30 pm PUJA Thursday : Vishnu Sahasranama 28 THAI POOSAM VENKATESWARA PUJA Friday: Lalitha Sahasranama Moon Rise 9.14 pm Sat, Sun & Holidays Moon Rise 9.13 pm Saturday: Venkateswara Suprabhatam SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI 8:30 am to 8:30 pm NEW YEAR DAY SANKATAHARA CHATURTHI Panchami 7.44 N Shashti 6.17 N Saptami 4.34 D Ashtami 2.36 D Navami 12.28 D Dasami 10.10 D Ekadasi 7.47 D Magha 8.26 D P Phalguni 7.47 D Hasta 5.39 N Chitra 4.16 N Swati 2.42 N Vishaka 1.02 N Dwadasi 5.23 N 3 4 U Phalguni 6.50 ND 5 6 7 8 9 Anuradha 11.19 N EKADASI PUJA AYYAPPAN PUJA Trayodasi 3.02 N Chaturdasi 12.52 N Amavasya 11.00 N Prathama 9.31 N Dwitiya 8.35 N Tritiya 8.15 N Chaturthi 8.38 N 10 Jyeshta 9.39 N 11 Mula 8.07 N 12 P Ashada 6.51 N 13 U Ashada 5.58 D 14 Shravana 5.34 D 15 Dhanishta 5.47 D 16 Satabhisha 6.39 N MAKARA SANKRANTHI PONGAL BHOGI MAKARA JYOTHI AYYAPPAN SRINIVASA KALYANAM PRADOSHA PUJA HANUMAN JAYANTHI PUSHYA / MAKARAM PUJA SHUKLA CHATURTHI PUJA THAI Panchami 9.44 N Shashti 11.29 N Saptami 1.45 N Ashtami 4.20 N Navami 6.59