Zionist Hegemony, the Settler Colonial Conquest of Palestine and the Problem with Conflict a Critical Genealogy of the Notion of Binary Conflict De Jong, A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Palestinian People

The Palestinian People The Palestinian People ❖ A HISTORY Baruch Kimmerling Joel S. Migdal HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England 2003 Copyright © 1994, 2003 by Baruch Kimmerling and Joel S. Migdal All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America An earlier version of this book was published in 1994 as Palestinians: The Making of a People Cataloging-in-Publication data available from the Library of Congress ISBN 0-674-01131-7 (cloth) ISBN 0-674-01129-5 (paper) To the Palestinians and Israelis working and hoping for a mutually acceptable, negotiated settlement to their century-long conflict CONTENTS Maps ix Preface xi Acknowledgments xxi Note on Transliteration xxiii Introduction xxv Part One FROM REVOLT TO REVOLT: THE ENCOUNTER WITH THE EUROPEAN WORLD AND ZIONISM 1. The Revolt of 1834 and the Making of Modern Palestine 3 2. The City: Between Nablus and Jaffa 38 3. Jerusalem: Notables and Nationalism 67 4. The Arab Revolt, 1936–1939 102 vii Contents Part Two DISPERSAL 5. The Meaning of Disaster 135 Part Three RECONSTITUTING THE PALESTINIAN NATION 6. Odd Man Out: Arabs in Israel 169 7. Dispersal, 1948–1967 214 8. The Feday: Rebirth and Resistance 240 9. Steering a Path under Occupation 274 Part Four ABORTIVE RECONCILIATION 10. The Oslo Process: What Went Right? 315 11. The Oslo Process: What Went Wrong? 355 Conclusion 398 Chronological List of Major Events 419 Notes 457 Index 547 viii MAPS 1. Palestine under Ottoman Rule 39 2. Two Partitions of Palestine (1921, 1949) 148 3. United Nations Recommendation for Two-States Solution in Palestine (1947) 149 4. -

1945-1949 Reasoned Views for Palestinian Arabs

1945-1949, A Collection of Reasoned Views for the dysfunctional state of the Palestinian Arab's political state of affairs 1. 1946 ---“The [Palestinian] Arabs are divided politically by the personal bickering of the leaders, which still center round the differences of the Husseinis and their rivals; and socially by the gap which separates the small upper class from the mass of the peasants—a gap which the new intelligentsia is not yet strong enough to bridge. Consequently they have developed no such internal democracy as have the Jews. That their divisions have not been overcome …is in part the result of a less acutely self-conscious nationalism that is found today among the Jews. It is, however, also the outcome of a failure of political responsibility. The Arab leaders, rejecting what they regard as a subordinate status in the Palestinian State, and viewing themselves as the proper heirs of the Mandatory Administration, have refused to develop a self-governing Arab community parallel to that of the Jews. Nor, so far, have they been prepared to see their position called in question by such democratic forms as elections for the Arab Higher Committee, or the formation of popularly based political parties. This failure is recognized by the new intelligentsia which, however, is unlikely to exercise power until it has the backing of a larger middle class.” As quoted in "Jews, Arabs, and Government," Chapter VIII, of The Report of the Anglo-American Commission of Inquiry, Lausanne, April 1946, p. 36. 2. 1940s forward …”decades of social change clearly contributed to [the Palestinian Arab] communal collapse and flight in the months of 1948- that is, rapid and chaotic breakdown and disintegration of village and urban political and social organization and leadership. -

Rhetorics of Belonging

Rhetorics of Belonging Postcolonialism across the Disciplines 14 Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 1 09/09/2013 11:17:03 Postcolonialism across the Disciplines Series Editors Graham Huggan, University of Leeds Andrew Thompson, University of Exeter Postcolonialism across the Disciplines showcases alternative directions for postcolonial studies. It is in part an attempt to counteract the dominance in colonial and postcolonial studies of one particular discipline – English literary/ cultural studies – and to make the case for a combination of disciplinary knowledges as the basis for contemporary postcolonial critique. Edited by leading scholars, the series aims to be a seminal contribution to the field, spanning the traditional range of disciplines represented in postcolonial studies but also those less acknowledged. It will also embrace new critical paradigms and examine the relationship between the transnational/cultural, the global and the postcolonial. Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 2 09/09/2013 11:17:03 Rhetorics of Belonging Nation, Narration, and Israel/Palestine Anna Bernard Liverpool University Press Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 3 09/09/2013 11:17:03 First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Anna Bernard The right of Anna Bernard to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or -

Targeted Exclusion at Israel's External Border Crossings

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2016 Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings Alexandra Goss Pomona College Recommended Citation Goss, Alexandra, "Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings" (2016). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 166. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/166 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Goss 1 Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings Alexandra Goss Readers: Professor Heidi Haddad Professor Zayn Kassam In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in International Relations at Pomona College Pomona College Claremont, CA April 29, 2016 Goss 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Introduction...............................................................................................5 I. Israel: State of Inclusion; State of Exclusion................................................5 II. Background of the Phenomenon...................................................................9 -

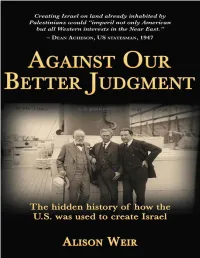

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

Arab Development Society

Arab Development Society GB165-0324 Reference code: GB165-0324 Title: Arab Development Society Collection Name of creators: Arab Development Society (1945-) Hodgkin, Edward Christian (1913-2006) Dates of creation of material: 1953-1984 Level of description: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Administrative history: Arab Development Society (1945-) The Arab Development Society was established in 1945 and worked to assure the welfare of Arab refugees following the British withdrawal from Palestine in 1948. Using the remainder of funds assigned to the Arab Development Society by the Arab League Economic Committee in 1945, combined with some personal capital, in 1949 Musa Alami engaged a project to dig for water on an area of land north-east of Jericho. The land was then cultivated and a small experimental farm set up. By 1951 the farm was more or less established and by 1955 was capable of large scale cultivation. The Farm was used to accommodate, educate and give vocational training to orphaned children. These children were not supported by the United Nations Relief Agency, as this only dealt with the heads of families. At the Arab Development Society Farm and Vocational Training Centre, orphaned Palestinian boys learned how to farm, were schooled and also trained in vocational skills including electrical engineering, weaving, carpentry and metalwork, for which there was significant demand in the Arab World at the time. The Arab Development Society Farm and Vocational Training Centre received significant damage during rioting in Nov 1955. The Centre managed to recover with the help of charitable donations, but was then more or less destroyed in the events of the 1967 war and its aftermath. -

Resisting Development: Land and Labour in Israeli, Palestinian and Sri Lankan Literature Nicola Anne Robinson Phd University Of

Resisting Development: Land and Labour in Israeli, Palestinian and Sri Lankan Literature ! Nicola Anne Robinson ! ! PhD ! University of York ! English ! September 2014 ! ! ABSTRACT ! This thesis examines literary representations which depict the evolution of capitalist development in narratives by Israeli, Palestinian and Sri Lankan writers. This comparative study is the first of its kind to bring the contexts of Israel/Palestine and Sri Lanka together. Collectively, my chapters analyse a range of literary texts by writers including Yosef Brenner, Sahar Khalifeh, Punyakante Wijenaike and Ambalavaner Sivanandan which explore the separatist ethnonational conflicts. I focus on narratives which critique the dominant discourse of development in their societies, through the formal and literary strategies that the writers utilise such as utopia, realism and melodrama. I argue that the texts I consider draw attention to the impact of uneven development on the content and form of literature in order to resist the current dispensation. This resistance is invaluable when one considers that development continues to be a contentious and divisive issue in Israel/Palestine, Sri Lanka and beyond today, yet one that has clear implications for sustainable peace. As a result, my research highlights that literature can play an invaluable role in anticipating, if not imagining, alternatives to the current world order. ! ! ! ! ! ! !2 Table of Contents ! ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................2 -

“A Young Man of Promise” Winner of the 2018 Ibrahim Dakkak Award for Outstanding Essay on Jerusalem Perspective

Winner of the 2018 Ibrahim Dakkak Award for Outstanding Essay on Jerusalem “A Young Man of If one has heard of Stephan Hanna Stephan at all, it is probably in connection with his Promise” ethnographic writings, published in the Journal of the Palestine Oriental Society Finding a Place for (JPOS) in the 1920s and 1930s.1 Stephan was Stephan Hanna one of what Salim Tamari tentatively calls a “Canaan Circle,” the nativist anthropologists Stephan in the History of Mandate Palestine, among whom the best 2 of Mandate Palestine known is Tawfiq Canaan. Along with Elias Haddad, Omar Salih al-Barghuti, Khalil Sarah Irving Totah, and others, they described and analyzed rural Palestinian culture and customs, seeing themselves as recording a disappearing way of life which, in its diversity, reflected the influences of myriad civilizations.3 This body of work, revived by Palestinian nationalist folklorists in the 1970s, is regarded as key to demonstrating the depth and longevity of Palestinian culture and identity, thus earning Stephan and his companions a place in the nationalist pantheon. However, as the research presented here highlights, his life story embodies two main themes above and beyond his ethnographic work. The first of these is Stephan’s contribution to Palestinian intellectual production during the Mandate era, which was greater than he has been given credit for. The second is a foregrounding of the complexity of life under the Mandate, in which relations between Palestinian Arabs and Jews and members of the British administration overlapped on a daily basis, defying clear lines and easy ex post facto assumptions about personal and professional Ibrahim Dakkak Award for relations between the different communities. -

Xorox Univorsky Microfilms 300 North Zaab Road Am Artur, Michigan 40106 T, R I 74-14,198

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the moat advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You w ill find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand comer of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again - beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

The Myth of Palestinian Centrality

The Myth of Palestinian Centrality Efraim Karsh Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 108 THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 108 The Myth of Palestinian Centrality Efraim Karsh The Myth of Palestinian Centrality Efraim Karsh © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] http://www.besacenter.org ISSN 1565-9895 July 2014 Cover picture: The State of Israel National Photo Collection/ Avi Ohayon The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies advances a realist, conservative, and Zionist agenda in the search for security and peace for Israel. It was named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace lay the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. The center conducts policy-relevant research on strategic subjects, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and Middle East regional affairs. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. In sponsoring these discussions, the BESA Center aims to stimulate public debate on, and consideration of, contending approaches to problems of peace and war in the Middle East. -

Desperately Nationalist, Yusif Sayigh, 1944 to 1948

Yusif Sayigh was born in Kharaba, Syria, in 1916. His father was Syrian, his mother was from al-Bassa in Palestine. The family was forced to leave Kharaba during the Druze uprising of 1925, going first to al- Bassa and then Tiberias, where they lived until 1948. Yusif went to the Gerard Institute (Sidon), where he received a scholarship to the American University of Beirut in 1934. He studied business administration. With six younger siblings–his father was a Presbyterian pastor–Yusif began working as soon as he got his Bachelors’ degree: first as an accountant in Beirut, and then as a school teacher in Iraq. In 1940, he returned to Palestine, finding a job in Tiberias until 1946, when he moved to work in Jerusalem. As he recounts here, Yusif became aware of Desperately the Palestinian issue as a young boy hearing of land sales in al-Bassa. At AUB, he followed Nationalist, the swirling debates of the time and joined the PPS (Partie Populaire Syrien), eventually becoming the ‘amid [head] of the Palestinian Yusif Sayigh, branch. What drew him to the PPS was not merely Antoun Sa’adeh’s nationalism and 1944 to 1948 charisma, but also the leader’s emphasis on modernization and discipline. It was here Excerpts from his that Yusif Sayigh developed the conviction recollections that the Arabs must learn to plan and systematize their activities. He approached Palestinian politics in the decade before the As told to and edited Nakba fully aware of the Zionist challenge, by Rosemary Sayigh critical of the limitations of the traditional Palestinian leadership, but also eager to act and contribute what he could. -

Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kent Academic Repository UNIVERSITY OF KENT SCHOOL OF ENGLISH ‘Bulwark against Asia’: Zionist Exclusivism and Palestinian Responses Submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. in Postcolonial Studies at University of Kent in 2015 by Nora Scholtes CONTENTS Abstract i Acknowledgments ii Abbreviations iii 1 INTRODUCTION: HERZL’S COLONIAL IDEA 1 2 FOUNDATIONS: ZIONIST CONSTRUCTIONS OF JEWISH DIFFERENCE AND SECURITY 40 2.1 ZIONISM AND ANTI-SEMITISM 42 2.2 FROM MINORITY TO MAJORITY: A QUESTION OF MIGHT 75 2.3 HOMELAND (IN)SECURITY: ROOTING AND UPROOTING 94 3 ERASURES: REAPPROPRIATING PALESTINIAN HISTORY 105 3.1 HIDDEN HISTORIES I: OTTOMAN PALESTINE 110 3.2 HIDDEN HISTORIES II: ARAB JEWS 136 3.3 REIMAGINING THE LAND AS ONE 166 4 ESCALATIONS: ISRAEL’S WALLING 175 4.1 WALLING OUT: FORTRESS ISRAEL 178 4.2 WALLED IN: OCCUPATION DIARIES 193 CONCLUSION 239 WORKS CITED 245 SUPPLEMENTARY BIBLIOGRAPHY 258 ABSTRACT This thesis offers a consideration of how the ideological foundations of Zionism determine the movement’s exclusive relationship with an outside world that is posited at large and the native Palestinian population specifically. Contesting Israel’s exceptionalist security narrative, it identifies, through an extensive examination of the writings of Theodor Herzl, the overlapping settler colonialist and ethno-nationalist roots of Zionism. In doing so, it contextualises Herzl’s movement as a hegemonic political force that embraced the dominant European discourses of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, including anti-Semitism. The thesis is also concerned with the ways in which these ideological foundations came to bear on the Palestinian and broader Ottoman contexts.