Phd Thesis Sophia Brown FINAL.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PALESTINIAN WALKS by Raja Shehadeh Chapter 1

PALESTINIAN WALKS by Raja Shehadeh Chapter 1 The sarha As a child I used to hear how my grandfather, Judge Saleem, liked nothing more than coming to Ramallah in the hot summer and going on a sarha with his cousin, Abu Ameen, leaving behind the humid coastal city of Jaffa and the stultifying colonial administration which he served and whose politics he detested. It was mainly young men who went on these expeditions. They would take a few provisions and go to the open hills, disappear for the whole day, sometimes for weeks and months. They often didn’t have a particular destination. To go on a sarha was to roam freely, at will, without restraint. The verb form of the word means to let the cattle out to pasture early in the morning, leaving them to wander and graze at liberty. The commonly used noun sarha is a colloquial corruption of the classical word. A man going on a sarha wanders aimlessly, not restricted by time and place, going where his spirit takes him to nourish his soul and rejuvenate himself. But not any excursion would qualify as a sarha. Going on a sarha implies letting go. It is a drug-free high, Palestinian-style. This book is a series of six sarhat (the plural of sarha) through time and place that take place on various Palestinian hills, sometimes alone and sometimes in the company of different Palestinians from the past and present – my grandfather’s cousin, the stonemason and farmer, and the human rights and political activists of more recent times, who were colleagues in my struggle against the destruction being wrought on the hills. -

Ed., with Penny Johnson

also by raja shehadeh Where the Line is Drawn Language of War, Language of Peace Shifting Sands (ed., with Penny Johnson) Occupation Diaries A Rift in Time Palestinian Walks When the Bulbul Stopped Singing Strangers in the House Photograph by Frédéric Stucin Photograph Frédéric by raja shehadeh is the author of the highly praised memoir Strangers in the House, and the enormously acclaimed When the Bulbul Stopped Singing, which was made into a stage play. He is a Palestinian lawyer and writer who lives in Ramallah. He is the founder of the pioneering, non-partisan human rights organisation Al-Haq, an affiliate of the International Commission of Jurists, and the author of several books about international law, human rights and the Middle East. Palestinian Walks published in 2007 won the Orwell Prize. Going Home.indd 2 16/04/2019 12:27 GOING HOME A walk through fifty years of occupation Raja SHEHADEH PROFILE BOOKS Going Home.indd 3 16/04/2019 12:27 First published in Great Britain in 2019 by PROFILE BOOKS LTD 3 Holford Yard Bevin Way London wc1x 9hd www.profilebooks.com Copyright © Raja Shehadeh, 2019 Photographs by Bassam Almohor 1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2 Typeset in Dante by MacGuru Ltd Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, Elcograf S.p.A. The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. -

“No Political Solution: the Occupation of Palestinian Narrative in Raja Shehadeh” John Randolph Leblanc University of Texas at Tyler

“No Political Solution: The Occupation of Palestinian Narrative in Raja Shehadeh” John Randolph LeBlanc University of Texas at Tyler For the Palestinian people, the “political” means being caught between “democratic” Israel’s occupation/domination and collaboration by their own democratically-elected “leaders.”1 Consequently, Palestinians have found it very difficult to find and articulate a functional political imaginary that addresses their everyday conditions and concerns. In this essay, I begin seeking possible sources for such an imaginary in the work of Raja Shehadeh, the lawyer, human rights activist, and writer from Ramallah. Of particular concern is his series of diaries written during various occupations and other Israeli incursions into the West Bank where he still lives.2 Shehadeh’s experience of everyday life under occupation and his various resistances to it force us to unmask the “democratic” at work in Palestine/Israel and push our understanding of the political beyond the Schmittian friend-enemy distinction to the need for a politics that serves human beings before even more abstract commitments. Since the summer of 1967, occupation/domination has been the principal mode of political interaction between the democratic state of Israel and the Palestinians in the West Bank and Gaza. While within the state of Israel we can find the forms and institutions of democracy at work, at least for its Jewish citizens,3 neither Israel’s justifications nor its administration of the frequent occupations of Palestinian territories are consistent with the stated ideals affiliated with liberal democracy: respect for persons and their property, freedom of movement, ordered access to basic services (from sustenance to work to education), and the substantive as well as procedural protections of the rule of law.4 Absent these possibilities and in the presence of the domination of occupation, we nonetheless may find the seeds of democratic possibilities in practices that emerge in resistance to occupation/domination. -

Palestine and Humanitarian Law: Israeli Practice in the West Bank and Gaza Carol Bisharat

Hastings International and Comparative Law Review Volume 12 Article 2 Number 2 Winter 1989 1-1-1989 Palestine and Humanitarian Law: Israeli Practice in the West Bank and Gaza Carol Bisharat Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_international_comparative_law_review Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Carol Bisharat, Palestine and Humanitarian Law: Israeli Practice in the West Bank and Gaza, 12 Hastings Int'l & Comp. L. Rev. 325 (1989). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_international_comparative_law_review/vol12/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings International and Comparative Law Review by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Palestine and Humanitarian Law: Israeli Practice in the West Bank and Gaza By CAROL BISHARAT Deputy PublicDefender, Santa Clara County; J.D., 1988, University of California,Hastings College of the Law; B.A., 1985, University of California,Berkeley. It was not as though there was a Palestinian people in Palestine consid- ering itself as a Palestinian people and we came and threw them out and took their country away from them. They did not exist. Prime Minister Golda Meir, Sunday London Times, 15 June 1969 AGAINST I am against my country's revolutionaries Wounding a sheath of wheat Against the child any child Carrying a hand grenade I am against my sister Feeling the muscle of a gun Against it all And yet What can a prophet do, a prophetess, When their eyes Are made to drink The sight of the raiders' hordes? I am against boys becoming heroes at ten Against the tree flowering explosives Against branches becoming scaffolds Against the rose-beds turning to trenches Against it all And yet When fire cremates my friends Hastings Int'l and Comparative Law Review [Vol. -

Zionist Hegemony, the Settler Colonial Conquest of Palestine and the Problem with Conflict a Critical Genealogy of the Notion of Binary Conflict De Jong, A

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Zionist hegemony, the settler colonial conquest of Palestine and the problem with conflict A critical genealogy of the notion of binary conflict de Jong, A. DOI 10.1080/2201473X.2017.1321171 Publication date 2018 Document Version Final published version Published in Settler Colonial Studies License CC BY-NC-ND Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): de Jong, A. (2018). Zionist hegemony, the settler colonial conquest of Palestine and the problem with conflict: A critical genealogy of the notion of binary conflict. Settler Colonial Studies, 8(3), 364-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2017.1321171 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) -

Rhetorics of Belonging

Rhetorics of Belonging Postcolonialism across the Disciplines 14 Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 1 09/09/2013 11:17:03 Postcolonialism across the Disciplines Series Editors Graham Huggan, University of Leeds Andrew Thompson, University of Exeter Postcolonialism across the Disciplines showcases alternative directions for postcolonial studies. It is in part an attempt to counteract the dominance in colonial and postcolonial studies of one particular discipline – English literary/ cultural studies – and to make the case for a combination of disciplinary knowledges as the basis for contemporary postcolonial critique. Edited by leading scholars, the series aims to be a seminal contribution to the field, spanning the traditional range of disciplines represented in postcolonial studies but also those less acknowledged. It will also embrace new critical paradigms and examine the relationship between the transnational/cultural, the global and the postcolonial. Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 2 09/09/2013 11:17:03 Rhetorics of Belonging Nation, Narration, and Israel/Palestine Anna Bernard Liverpool University Press Bernard, Rhetorics of Belonging.indd 3 09/09/2013 11:17:03 First published 2013 by Liverpool University Press 4 Cambridge Street Liverpool L69 7ZU Copyright © 2013 Anna Bernard The right of Anna Bernard to be identified as the author of this book has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or -

Targeted Exclusion at Israel's External Border Crossings

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2016 Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings Alexandra Goss Pomona College Recommended Citation Goss, Alexandra, "Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings" (2016). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 166. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/166 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Goss 1 Banned from the Only Democracy in the Middle East: Targeted Exclusion at Israel’s External Border Crossings Alexandra Goss Readers: Professor Heidi Haddad Professor Zayn Kassam In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Bachelor of Arts in International Relations at Pomona College Pomona College Claremont, CA April 29, 2016 Goss 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements........................................................................................................4 Chapter 1: Introduction...............................................................................................5 I. Israel: State of Inclusion; State of Exclusion................................................5 II. Background of the Phenomenon...................................................................9 -

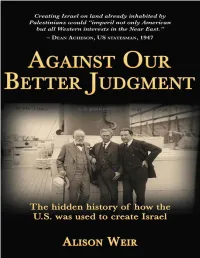

Against Our Better Judgment: the Hidden History of How the U.S. Was

Against Our Better Judgment The hidden history of how the U.S. was used to create Israel ALISON WEIR Copyright © 2014 Alison Weir All rights reserved. DEDICATION To Laila, Sarah, and Peter CONTENTS Aknowledgments Preface Chapter One: How the U.S. “Special Relationship” with Israel came about Chapter Two: The beginnings Chapter Three: Louis Brandeis, Zionism, and the “Parushim” Chapter Four: World War I & the Balfour Declaration Chapter Five: Paris Peace Conference 1919: Zionists defeat calls for self- determination Chapter Six: Forging an “ingathering” of all Jews Chapter Seven: The modern Israel Lobby is born Chapter Eight: Zionist Colonization Efforts in Palestine Chapter Nine: Truman Accedes to Pro-Israel Lobby Chapter Ten: Pro-Israel Pressure on General Assembly Members Chapter Eleven: Massacres and the Conquest of Palestine Chapter Twelve: U.S. front groups for Zionist militarism Chapter Thirteen: Infiltrating displaced person’s camps in Europe to funnel people to Palestine Chapter Fourteen: Palestinian refugees Chapter Fifteen: Zionist influence in the media Chapter Sixteen: Dorothy Thompson, played by Katharine Hepburn & Lauren Bacall Works Cited Further Reading Endnotes ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to Katy, who plowed through my piles of obscure books and beyond to check it; to Sarah, whose design so enhanced it; to Monica, whose splendid work kept things together; and to the special, encouraging friends (you know who you are) who have made this all possible. Above all, I am profoundly grateful to the authors and editors who have produced superb work on this issue for so many years, many receiving little personal gain despite the excellence and dedication of their labors. -

Resisting Development: Land and Labour in Israeli, Palestinian and Sri Lankan Literature Nicola Anne Robinson Phd University Of

Resisting Development: Land and Labour in Israeli, Palestinian and Sri Lankan Literature ! Nicola Anne Robinson ! ! PhD ! University of York ! English ! September 2014 ! ! ABSTRACT ! This thesis examines literary representations which depict the evolution of capitalist development in narratives by Israeli, Palestinian and Sri Lankan writers. This comparative study is the first of its kind to bring the contexts of Israel/Palestine and Sri Lanka together. Collectively, my chapters analyse a range of literary texts by writers including Yosef Brenner, Sahar Khalifeh, Punyakante Wijenaike and Ambalavaner Sivanandan which explore the separatist ethnonational conflicts. I focus on narratives which critique the dominant discourse of development in their societies, through the formal and literary strategies that the writers utilise such as utopia, realism and melodrama. I argue that the texts I consider draw attention to the impact of uneven development on the content and form of literature in order to resist the current dispensation. This resistance is invaluable when one considers that development continues to be a contentious and divisive issue in Israel/Palestine, Sri Lanka and beyond today, yet one that has clear implications for sustainable peace. As a result, my research highlights that literature can play an invaluable role in anticipating, if not imagining, alternatives to the current world order. ! ! ! ! ! ! !2 Table of Contents ! ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................2 -

Raja Shehadeh

Interview Dr. Daniel Stahl Quellen zur Geschichte der Menschenrechte Raja Shehadeh Criticism of Israeli human rights violations had been constantly addressed by the Eastern bloc and the decolonized states at the UN. However, in the Western public realm, information about Israeli human rights violations in the occupied territories only started to circulate in the beginning of the 1980s when organizations like the International Commission of Jurists, Amnesty International, and Human Rights Watch seized on and began to report on the issue. Raja Shehadeh (born in 1951), a young lawyer who had studied in London, played a crucial role in providing these organizations with information. He founded Al-Haq, the first Palestinian human rights organization, which enabled him to systematically collect evidence of state violence in the occupied territories. At the same time, working as a lawyer, he had access to information about many different cases of human rights violations. Interview The interview with Raja Shehadeh was conducted by Dr. Daniel Stahl, coordinator of the Study Group Human Rights in the 20th Century, on September 5, 2016, at the lawyer’s office in Ramallah. The only contact between the two before the interview had been via Email. Beginning at 11 PM, Shehadeh spoke for two and a half hours in a fluent English about his experiences, interrupted once in a while by a phone call. The interview was conducted in connection with two other conversations with Bassem Eid and Gadi Algazi about human rights activism in Israel. Stahl First of all, I would like to hear about your family background. Shehadeh I was born in Ramallah in 1951. -

Edward W. Said : Sélection Bibliographique De La Bibliothèque De L’Institut Du Monde Arabe Version Octobre 2010

Edward W. Said : sélection bibliographique de la Bibliothèque de l’Institut du monde arabe Version Octobre 2010 Edward W. Said (1935-2003) Sélection bibliographique Source photo : flickr.com Edward W. Said, universitaire et intellectuel palestino-américain, s’est éteint à New-York le jeudi 25 septembre 2003. Tout le monde reconnaît aujourd’hui l’apport décisif de ses essais d’anthropologie culturelle, notamment L’Orientalisme et Culture et impérialisme. Professeur de littérature comparée à l’Université de Columbia, critique littéraire et principal défenseur de la cause palestinienne aux Etats-Unis, Edward W. Said est l’un des intellectuels majeurs du monde arabe contemporain. Cette sélection bibliographique rassemble les ouvrages et articles consultables à la bibliothèque de l’IMA. Sommaire Edward W. Said, auteur ................................................................................................. 2 Mémoires, Essais, Témoignages, Entretiens .......................................................................... 2 Sur l’orientalisme ................................................................................................................... 4 Sélection d’Articles .............................................................................................................. 4 Sur la question palestinienne ................................................................................................. 5 Sélection d’Articles ............................................................................................................. -

Living in Legal Limbo: Israel's Settlers in Occupied Palestinian Territory

Pace International Law Review Volume 10 Issue 1 Summer 1998 Article 1 June 1998 Living in Legal Limbo: Israel's Settlers in Occupied Palestinian Territory John Quigley Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr Recommended Citation John Quigley, Living in Legal Limbo: Israel's Settlers in Occupied Palestinian Territory, 10 Pace Int'l L. Rev. 1 (1998) Available at: https://digitalcommons.pace.edu/pilr/vol10/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Law at DigitalCommons@Pace. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pace International Law Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Pace. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PACE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF LAW INTERNATIONAL LAW REVIEW Volume 10 1998 ARTICLE LIVING IN LEGAL LIMBO: ISRAEL'S SETTLERS IN OCCUPIED PALESTINIAN TERRITORY John Quigley* I. Introduction ....................................... 2 II. Israel's Settlem ents ............................... 3 A. Acquisition of the Territory by Israel .......... 3 B. Construction of Settlements ................... 5 C. Settlement Construction Since the Israel- P.L.O. Agreem ents ............................. 7 III. Legality of Israel's Settlements .................... 11 A. Belligerent Occupation and Settlements ....... 11 B. View of International Community ............. 13 C. Arguments in Favor of the Legality of Israel's Settlem ents .................................... 14 1. Transfer ................................... 14 2. Displacem ent .............................. 15 3. Security .................................... 15 * Professor of Law, Ohio State University, LL.B., M.A. 1966, Harvard Law School. The writer is author of PALESTINE AND ISRAEL: A CHALLENGE TO JUSTICE (1990), and FLIGHT INTO THE MAELSTROM: SOVIET IMMIGRATION TO ISRAEL AND MID- DLE EAST PEACE (1997).