Evaluation of Pilot Programme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

School and College (Key Stage 5)

School and College (Key Stage 5) Performance Tables 2010 oth an West Yorshre FE12 Introduction These tables provide information on the outh and West Yorkshire achievement and attainment of students of sixth-form age in local secondary schools and FE1 further education sector colleges. They also show how these results compare with other Local Authorities covered: schools and colleges in the area and in England Barnsley as a whole. radford The tables list, in alphabetical order and sub- divided by the local authority (LA), the further Calderdale education sector colleges, state funded Doncaster secondary schools and independent schools in the regional area with students of sixth-form irklees age. Special schools that have chosen to be Leeds included are also listed, and a inal section lists any sixth-form centres or consortia that operate otherham in the area. Sheield The Performance Tables website www. Wakeield education.gov.uk/performancetables enables you to sort schools and colleges in ran order under each performance indicator to search for types of schools and download underlying data. Each entry gives information about the attainment of students at the end of study in general and applied A and AS level examinations and equivalent level 3 qualiication (otherwise referred to as the end of ‘Key Stage 5’). The information in these tables only provides part of the picture of the work done in schools and colleges. For example, colleges often provide for a wider range of student needs and include adults as well as young people Local authorities, through their Connexions among their students. The tables should be services, Connexions Direct and Directgov considered alongside other important sources Young People websites will also be an important of information such as Ofsted reports and school source of information and advice for young and college prospectuses. -

Leeds Secondary Admission Policy for September 2021 to July 2022

Leeds Secondary Admission Policy for September 2021 to July 2022 Latest consultation on this policy: 13 December 2019 and 23 January 2020 Policy determined on: 12 February 2020 Policy determined by: Executive Board Admissions policy for Leeds community secondary schools for the academic year September 2021 – July 2022 The Chief Executive makes the offer of a school place at community schools for Year 7 on behalf of Leeds City Council as the admissions authority for those schools. Headteachers or school-based staff are not authorised to offer a child a place for these year groups for September entry. The authority to convey the offer of a place has been delegated to schools for places in other year groups and for entry to Year 7 outside the normal admissions round. This Leeds City Council (Secondary) Admission Policy applies to the schools listed below. The published admission number for each school is also provided for September 2021 entry: School name PAN Allerton Grange School 240 Allerton High School 220 Benton Park School 300 Lawnswood School 270 Roundhay All Through School (Yr7) 210 Children with an education, health and care plan will be admitted to the school named on their plan. Where there are fewer applicants than places available, all applicants will be offered a place. Where there are more applicants than places available, we will offer places to children in the following order of priority. Priority 1 a) Children in public care or fostered under an arrangement made by the local authority or children previously looked after by a Local Authority. (see note 1) b) Pupils without an EHC plan but who have Special Educational Needs that can only be met at a specific school, or with exceptional medical or mobility needs, that can only be met at a specific school. -

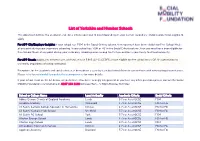

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools

List of Yorkshire and Humber Schools This document outlines the academic and social criteria you need to meet depending on your current secondary school in order to be eligible to apply. For APP City/Employer Insights: If your school has ‘FSM’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling. If your school has ‘FSM or FG’ in the Social Criteria column, then you must have been eligible for Free School Meals at any point during your secondary schooling or be among the first generation in your family to attend university. For APP Reach: Applicants need to have achieved at least 5 9-5 (A*-C) GCSES and be eligible for free school meals OR first generation to university (regardless of school attended) Exceptions for the academic and social criteria can be made on a case-by-case basis for children in care or those with extenuating circumstances. Please refer to socialmobility.org.uk/criteria-programmes for more details. If your school is not on the list below, or you believe it has been wrongly categorised, or you have any other questions please contact the Social Mobility Foundation via telephone on 0207 183 1189 between 9am – 5:30pm Monday to Friday. School or College Name Local Authority Academic Criteria Social Criteria Abbey Grange Church of England Academy Leeds 5 7s or As at GCSE FSM Airedale Academy Wakefield 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints Catholic College Specialist in Humanities Kirklees 4 7s or As at GCSE FSM or FG All Saints' Catholic High -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Leeds School Forum, 10/10/2019

Public Document Pack LEEDS SCHOOL FORUM Meeting to be held in Merrion House, Meeting Suite rooms 3 and 4, second floor on Thursday, 10th October, 2019 at 4.30 pm MEMBERSHIP Dave Kagai, A. Primary Governors - St Nicholas Primary Sara Nix, A. Primary Governors - Rawdon Littlemoor Primary John Garvani (LSF), A. Primary Governors - Broadgate Primary School Jim Ebbs, A. Primary Governors - Woodlesford Primary John Hutchinson, B. Primary Heads - St Theresa's Catholic Primary Claire Harrison, B. Primary Heads - Wetherby Deighton Gates Primary Barbara Trayer, B. Secondary Governors - Allerton Grange Secondary Helen Stott, B. Primary Heads - Allerton C of E Primary Peter Harris, B. Primary Heads - Farsley Farfield Primary Julie Harkness, B. Primary Heads - Carr Manor Community school - Primary Phase Jo Smithson, B. Primary Heads - Greenhill Primary David Webster, C. Secondary Governors - Pudsey Grangefield Delia Martin, D. Secondary Heads - Benton Park Lucie Lakin, D. Secondary Heads - Wetherby High David Gurney, E. Academy Reps - Cockburn School Adam Ryder, E. Academy Reps - The Morley Academy John Thorne, E. Academy Reps - Co-operative Academy Priesthorpe Emma Lester, E. Academy Reps - Woodkirk Academy Ian Goddard, E. Academy Reps - Ebor Gardens/Victoria Primary Ac Siobhan Roberts, E. Academy Reps - Cockburn John Charles Academy Joe Barton, E. Academy Reps - Woodkirk Academy Anna Mackenzie, E. Academy Reps - Richmond Hill Academy Scott Jacques, F. Academy (Special) - Springwell Leeds East Academy Ben Mallinson, G. Academy (AP) - The Stephen Longfellow Academy Diane Reynard, I. Special School Principal - East / NW SILC - SILC Principals Patrick Murphy, J. Non School - Schools JCC Angela Cox, J. Non School - Leeds Catholic Diocese Councillor Dan Cohen, J. -

Art and Design Teacher, Roundhay High School

Thanks to: Key contributors to the English Materials: Lynne Ware, Beckfoot Upper Heaton High School, Bradford Gill Morley, Priesthorpe High School, Leeds Mat Carmichael, Roundhay High School, Leeds Special thanks to students from Benton Park High School, Leeds for all the images included in these materials. Other W.C.T. Subject Teachers: Lorraine Waterson, Head of History and Politics, Rodillian Academy, Leeds Hayley Ashe, History, Rodillian Academy, Leeds Richard Baker, Head of History, Lawnswood High School, Leeds Andrew Bennett, Head of History, Allerton Grange High School, Leeds Lydia Jackson, History Teacher, Abbey Grange C of E High School, Leeds Judith Hart, Head of History, Priesthorpe High School, Leeds Rachel Wilde, History Teacher, The Morley Academy, Leeds Tom Butterworth, Head of Geography, Priesthorpe High School, Leeds Jane Dickinson, Geography Teacher, The Morley Academy, Leeds Rachel Gibson, Head of Geography, Allerton High School, Leeds Michelle Minton, The Morley Academy, Leeds Ian Underwood, Roundhay High School, Leeds Clair Atkins, Head of MFL, Lawnswood High School, Leeds Sue Dixon, Art and Design, Benton Park High School, Leeds Thanks also for invaluable insights and support from: Diane Maguire, Lecturer in Education, Leeds Trinity University Mary Maybank, Psychology and Sociology Teacher, Leeds Liz Allum and Barbara Lowe, Reading International Solidarity Centre, Reading Humanities Education Centre, Tower Hamlets, London Paul Brennen, Deputy Director Leeds Children and Young Peoples’ Service, Leeds Steve Pottinger for permission to reprint #foxnewsfact from More Bees Bigger Bonnets published by Ignite Books Design by Hardwired Users may copy pages from this pack for educational use, but no part may be reproduced for commercial use without prior permission from Leeds DEC. -

Address Lest

Headteacher School Name Address Telephone Fax Headteacher Email Butcher Hill West Park LEEDS LS16 5EA Carol Kitson Abbey Grange C Of E Academy 0113 275 7877 0113 275 4794 [email protected] School Lane Aberford LEEDS Aberford Church of England Voluntary Controlled Primary LS25 3BU Philippa Boulding School 0113 281 3302 0113 281 3302 [email protected] Tile Lane Leeds LS16 8DY Stephen Boothroyd Adel Primary School 0113 230 1116 0113 230 1117 [email protected] Long Causeway Adel LEEDS LS16 8EX Janice Turner Adel St John The Baptist Church of England Primary School 0113 214 1040 0113 230 1216 [email protected] Cross Aysgarth Mount LEEDS LS9 9AD David Pattison All Saint's Richmond Hill Church of England Primary School 0113 2143056 0113 2401333 [email protected] Leeds Road Allerton Bywater Castleford WF10 2DR Richard Cairns Allerton Bywater Primary School 0113 3368240 01977 517399 [email protected] Lingfield Approach Leeds LS17 7HL Helen Stott Allerton Church of England Primary School 0113 293 0699 0113 293 0699 [email protected] Talbot Avenue Moortown LEEDS LS17 6SF Rick Whittaker Allerton Grange School 0113 3368585 0113 2693243 [email protected] King Lane Moortown LEEDS LS17 7AG Elaine Silson Allerton High School 0113 336 8484 0113 393 0631 [email protected] Cranmer Rise Alwoodley Leeds LS17 5HX Jane Langley Alwoodley Primary School 0113 268 6104 0113 266 2044 [email protected] Salisbury Terrace Armley LEEDS LS12 2AY christine burrill Armley -

2019 Spring Messenger

Mount St Maryʼs Catholic High School Educating The Individual For The Benefit Of All The news magazine for Mount St Maryʼs Catholic High School Mount St Mary’s Catholic High School English and Performing Arts faculty proudly presents Spring 2019 MSM Messenger 1 As we approach our Spring break we find ourselves slightly out The news magazine for Mount St Maryʼs Catholic High School of sync with some Leeds schools and yet still a little while from the Feast of Easter. Our students continue to throw themselves into a whole range of activities and learning opportunities every chance they get. This term we have launched our new MSM ASPIRE Award, an online log which allows all our students to record their development through; Attitudes to learning, Success in their student graduation challenges, PSHCE and CEIAG, Involved in all aspects of life, Registration and assembly roles and lastly Evidencing their contributions and giving back in school, at home and in the community. Students and staff have embraced this new initiative to bring together all these aspects of school life in which our students excel. Shortly after Easter Year 11 will find themselves entering the world of GCSE exams and we will amend their timetables to provide focused preparation for each subjectʼs exam. I am sure you will all join me in wishing them well and supporting them at this stressful time. We wish Mr Addison, Assistant Head teacher and SENDCO, well as he moves to a new role in Bradford at Easter. Whilst I am sure he is excited he will also miss the MSM community. -

Allerton High School Cover Report 110621 PDF 191 KB

Report author: Janet Carter Tel: 87226 Report of Director of Children and Families Report to Executive Board Date: 23 June 2021 Subject: Outcome of consultation to permanently increase learning places at Allerton High School from September 2022 Are specific electoral wards affected? Yes No If yes, name(s) of ward(s): Adel & Wharfedale, Alwoodley and Moortown Has consultation been carried out? Yes No Are there implications for equality and diversity and cohesion and Yes No integration? Will the decision be open for call-in? Yes No Does the report contain confidential or exempt information? Yes No If relevant, access to information procedure rule number: Appendix number: Summary 1. Main issues This report contains details of a proposal brought forward to meet the local authority’s duty to ensure a sufficiency of school places. The changes that are proposed form prescribed alterations under the Education and Inspections Act 2006. The School Organisation (Prescribed Alterations to Maintained Schools) (England) Regulations 2013 and accompanying statutory guidance set out the process which must be followed when making such changes. The statutory process to make these changes varies according to the nature of the change and status of the school. The process followed in respect of this proposal is detailed in this report. The decision maker in these cases remains the local authority (LA). A consultation on a proposal to permanently expand Allerton High School from a capacity of 1100 to 1400 students by increasing the admission number in Year 7 from 220 to 280 with effect from September 2022 took place between 31 March and 7 May 2021. -

Head of History and Politics, Rodillian Academy

“As an engineer I‘ve travelled the world widely for business. It’s been really eye- opening hearing about other people’s perceptions of history… and I’ve found myself in a few uncomfortable situations in countries like China, Japan, Germany and Iran. I’ve learned so much about other countries views of the British and history – which are sometimes very different to ours; but it would have been really helpful (and less Thanks to: embarrassing) if I’d learned this at school!” Key contributors to the History Materials: Peter H., Engineer Lorraine Waterson, Head of History and Politics, Rodillian Academy, Leeds Hayley Ashe, History Teacher, Rodillian Academy, Leeds Contents Richard Baker, Head of History, Lawnswood High School, Leeds Introduction 4 Andrew Bennett, Head of History, Allerton Grange High School, Leeds Delivering Spiritual, Moral, Social and Cultural aspects of learning 6-9 Lydia Jackson, History Teacher, Abbey Grange C of E High School, Leeds Curriculum Review 10-12 Judith Hart, Head of History, Priesthorpe High School, Leeds Reflection criteria for teachers 13 Rachel Wilde, History Teacher, The Morley Academy, Leeds Quality principles in Global Education 14 Lynne Ware, Beckfoot Upper Heaton High School, Bradford Global Learning Teaching Toolkits 15 Other Subject Teachers: Steve Ablett, History Teacher, Dixon’s Academy Tom Butterworth, Head of Geography, Priesthorpe High School, Leeds Gill Morley, Priesthorpe High School, Leeds Jane Dickinson, Geography Teacher, The Morley Academy, Leeds Sue Dixon, Head of Art and Design, Benton -

School Or Venue Phase Cluster Summer Event Abbey Grange Church of England High School Secondary Inner North West Hub Nil Return the N.E.X.T

School or Venue Phase Cluster Summer event Abbey Grange Church of England High School Secondary Inner North West Hub Nil return The N.E.X.T. cluster will have a cluster coordinator by January 2008. Two High schools in the Cluster, Allerton Grange and Roundhay. Allerton Grange hosted a G & T Drama summer school, 1 week, 30 students Allerton Grange School Secondary N.E.X.T. (NE) Allerton High School Secondary Alwoodley (NE) Shared provision with Carr Manor Benton Park School Secondary Aireborough (NW) Nil return Boston Spa School Secondary EPOS Boston Spa (NE) Nil return Brigshaw High School and Language College Secondary Brigshaw (E) G & T East Leeds Oriental project, 1 week, 30 students Bruntcliffe School Secondary Morley North (S) Nil return Cardinal Heenan Catholic High School Secondary Alwoodley (NE) Letting to Leeds United for the Sports Hall G & T PE, shared with Allerton High, 1 week, 60 students. 2 additional Summer Schools organized through NEtWORKS Extended Services, Multi Sports Summer Camp for 8yrs – 12yrs (2 weeks provision which attracted over 100 young people. G&T Dance Summer School for cluster primary schools, targeted at Yr5 & Carr Manor High School Secondary NEtWORKS (NE) Yr6 pupils, 30 pupils in attendance (1week programme). City of Leeds School Secondary Open XS (NW) Nil return Cockburn College of Arts Secondary Middleton (S) G & T Science Fiction CSI, 2 weeks, 30 students Corpus Christi Catholic College Secondary Templenewsam Halton HO (E)G & T PE, 2 weeks, 15 students Crawshaw School Secondary Pudsey (W) G & T mixed -

Leeds Municipal Grammar Schools 1944-72

The Yorkshire Archaeological & Historical Society Leeds municipal grammar schools 1944-72 Anthony Silson BSc (Hons) MSc PGCE FRGS Leeds municipal grammar schools 1944-72 Anthony Silson BSc Msc FRGS Part I The organisation of education in the borough of Leeds 1944-72 In retrospect, the years between 1944 and 1972 can be interpreted as a prolonged period of transition in educational organisation from very limited secondary school provision, and that chiefly in grammar schools, to universal secondary education provided by comprehensive schools. Between 1918 and 1944, the majority of Leeds’ pupils were educated in all-age (5-14) elementary schools. A few pupils were educated in private schools and some in partly publicly funded municipal grammar schools. The latter had many fee-paying pupils, some of whom had already attended the fee-paying kindergarten of their respective high schools. Some pupils attended municipal grammar schools by dint of gaining a scholarship at eleven; such pupils were non-fee paying. The 1944 Education Act was one of the finest pieces of twentieth century legislation. By this Act, the school leaving age was raised to fifteen, secondary education was to be provided for everyone, fee-paying was abolished in municipal grammar schools, and pupils were to be educated according to their ages, abilities and aptitudes. As early as 1946, Leeds City Council had shown interest in providing comprehensive secondary schools. However, Leeds then had few secondary schools. Consequently, as an interim measure, the council decided to provide secondary education for all by opening additional secondary modern schools to replace elementary schools, and by selecting pupils for its then eight grammar and two technical schools. -

CPD Programme 2020/21 CPD Programme 2020/21

CPD Programme 2020/21 CPD Programme 2020/21 How to book The YTSA CPD programme 2020/21 This year, the Monday programme (including networking CPD leads from all partner schools continue to meet regularly to identify the training priorities for events) will be delivered virtually via Teams. In order to their teaching staff. This shapes our Continuing Professional Development Programme, as below: facilitate easy access and maximum attendance at these weekly training sessions, we have agreed that all YTSA member Strand 1 - Monday training sessions Strand 3 - Conferences schools can attend them free of charge. Our Monday sessions run throughout the Autumn and This year, we will run the NQT conference (parts 1 and This makes the booking process very easy -all attendees can Spring terms, from 4-5pm most weeks, and are facilitated 2) and the RQT conference in January. There is also the simply book themselves on via Eventbrite at no cost to their by various schools from across the Teaching Alliance. rescheduled conference for School leaders in March. school. They are based on up to date and reliable educational research, delivered by practising teachers and school Other training events ie conferences and the NPQML leaders. Strand 4 - National Professional Qualifications qualification, have their own charging structure - this cost is This year, due to the Covid-19 restrictions on large groups kept to a minimum and details are on Eventbrite. and non essential travel (at the time of writing) we have Allerton High School are once again offering the NPQML decided to run these sessions virtually using the Teams course, and have delayed the start until January 2021.