Scaling of Frond Form in Hawaiian Tree Fern Cibotium Glaucum: Compliance with Global Trends and Application for Field Estimation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Keauhou Bird Conservation Center

KEAUHOU BIRD CONSERVATION CENTER Discovery Forest Restoration Project PO Box 2037 Kamuela, HI 96743 Tel +1 808 776 9900 Fax +1 808 776 9901 Responsible Forester: Nicholas Koch [email protected] +1 808 319 2372 (direct) Table of Contents 1. CLIENT AND PROPERTY INFORMATION .................................................................... 4 1.1. Client ................................................................................................................................................ 4 1.2. Consultant ....................................................................................................................................... 4 2. Executive Summary .................................................................................................. 5 3. Introduction ............................................................................................................. 6 3.1. Site description ............................................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. Parcel and location .................................................................................................................. 6 3.1.2. Site History ................................................................................................................................ 6 3.2. Plant ecosystems ............................................................................................................................ 6 3.2.1. Hydrology ................................................................................................................................ -

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska

Ferns of the National Forests in Alaska United States Forest Service R10-RG-182 Department of Alaska Region June 2010 Agriculture Ferns abound in Alaska’s two national forests, the Chugach and the Tongass, which are situated on the southcentral and southeastern coast respectively. These forests contain myriad habitats where ferns thrive. Most showy are the ferns occupying the forest floor of temperate rainforest habitats. However, ferns grow in nearly all non-forested habitats such as beach meadows, wet meadows, alpine meadows, high alpine, and talus slopes. The cool, wet climate highly influenced by the Pacific Ocean creates ideal growing conditions for ferns. In the past, ferns had been loosely grouped with other spore-bearing vascular plants, often called “fern allies.” Recent genetic studies reveal surprises about the relationships among ferns and fern allies. First, ferns appear to be closely related to horsetails; in fact these plants are now grouped as ferns. Second, plants commonly called fern allies (club-mosses, spike-mosses and quillworts) are not at all related to the ferns. General relationships among members of the plant kingdom are shown in the diagram below. Ferns & Horsetails Flowering Plants Conifers Club-mosses, Spike-mosses & Quillworts Mosses & Liverworts Thirty of the fifty-four ferns and horsetails known to grow in Alaska’s national forests are described and pictured in this brochure. They are arranged in the same order as listed in the fern checklist presented on pages 26 and 27. 2 Midrib Blade Pinnule(s) Frond (leaf) Pinna Petiole (leaf stalk) Parts of a fern frond, northern wood fern (p. -

Lesson 6: Plant Reproduction

LESSON 6: PLANT REPRODUCTION LEVEL ONE Like every living thing on earth, plants need to make more of themselves. Biological structures wear out over time and need to be replaced with new ones. We’ve already looked at how non-vascular plants reproduce (mosses and liverworts) so now it’s time to look at vascular plants. If you look back at the chart on page 17, you will see that vascular plants are divided into two main categories: plants that produce seeds and plants that don’t produce seeds. The vascular plants that do not make seeds are basically the ferns. There are a few other smaller categories such as “horse tails” and club mosses, but if you just remember the ferns, that’s fine. So let’s take a look at how ferns make more ferns. The leaves of ferns are called fronds, and brand new leaves that have not yet totally uncoiled are called fiddleheads because they look like the scroll-shaped end of a violin. Technically, the entire frond is a leaf. What looks like a stem is actually the fern’s equivalent of a petiole. (Botanists call it a stipe.) The stem of a fern plant runs under the ground and is called a rhizome. Ferns also have roots, like all other vascular plants. The roots grow out from the bottom of the rhizome. Ferns produce spores, just like mosses do. At certain times of the year, the backside of some fern fronds will be covered with little dots called sori. Sori is the plural form, meaning more than one of them. -

Apapane (Himatione Sanguinea)

The Birds of North America, No. 296, 1997 STEVEN G. FANCY AND C. JOHN RALPH 'Apapane Himatione sanguinea he 'Apapane is the most abundant species of Hawaiian honeycreeper and is perhaps best known for its wide- ranging flights in search of localized blooms of ō'hi'a (Metrosideros polymorpha) flowers, its primary food source. 'Apapane are common in mesic and wet forests above 1,000 m elevation on the islands of Hawai'i, Maui, and Kaua'i; locally common at higher elevations on O'ahu; and rare or absent on Lāna'i and Moloka'i. density may exceed 3,000 birds/km2 The 'Apapane and the 'I'iwi (Vestiaria at times of 'ōhi'a flowering, among coccinea) are the only two species of Hawaiian the highest for a noncolonial honeycreeper in which the same subspecies species. Birds in breeding condition occurs on more than one island, although may be found in any month of the historically this is also true of the now very rare year, but peak breeding occurs 'Ō'ū (Psittirostra psittacea). The highest densities February through June. Pairs of 'Apapane are found in forests dominated by remain together during the breeding 'ōhi'a and above the distribution of mosquitoes, season and defend a small area which transmit avian malaria and avian pox to around the nest, but most 'Apapane native birds. The widespread movements of the 'Apapane in response to the seasonal and patchy distribution of ' ōhi'a The flowering have important implications for disease Birds of transmission, since the North 'Apapane is a primary carrier of avian malaria and America avian pox in Hawai'i. -

Ferns Robert H

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Illustrated Flora of Illinois Southern Illinois University Press 10-1999 Ferns Robert H. Mohlenbrock Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Mohlenbrock, Robert H., "Ferns" (1999). Illustrated Flora of Illinois. 3. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southern Illinois University Press at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illustrated Flora of Illinois by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS ROBERT H. MOHLENBROCK, General Editor THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS s Second Edition Robert H. Mohlenbrock SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS Carbondale and Edwardsville COPYRIGHT© 1967 by Southern Illinois University Press SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT © 1999 by the Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 02 01 00 99 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mohlenbrock, Robert H., 1931- Ferns I Robert H. Mohlenbrock. - 2nd ed. p. em.- (The illustrated flora of Illinois) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Ferns-Illinois-Identification. 2. Ferns-Illinois-Pictorial works. 3. Ferns-Illinois-Geographical distribution-Maps. 4. Botanical illustration. I. Title. II. Series. QK525.5.I4M6 1999 587'.3'09773-dc21 99-17308 ISBN 0-8093-2255-2 (cloth: alk. paper) CIP The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.§ This book is dedicated to Miss E. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

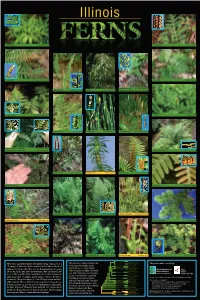

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants. -

100 Years of Change in the Flora of the Carolinas

Flora of the Carolinas, Virginia, Georgia, and surrounding areas Working Draft of 11 January 2007 by Alan S. Weakley University of North Carolina Herbarium (NCU) North Carolina Botanical Garden University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Campus Box 3280 Chapel Hill NC 27599-3280 TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents THE FLORA .................................................................................................................................................................................................................6 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ............................................................................................................................................................................................9 FERNS AND “FERN ALLIES”............................................................................................................................................................................10 ASPLENIACEAE Frank 1877 (Spleenwort Family) ........................................................................................................................................17 AZOLLACEAE Wettstein 1903 (Mosquito Fern Family) .................................................................................................................................20 BLECHNACEAE (C. Presl) Copeland 1947 (Deer Fern Family) ...................................................................................................................21 DENNSTAEDTIACEAE Pichi Sermolli 1970 (Bracken Family) ....................................................................................................................22 -

Transformative Paleobotany

Chapter 6 Lower Permian Flora of the Sanzenbacher Ranch, Clay County, Texas William A. DiMichele1, Robert W. Hook2, Hans Kerp3, Carol L. Hotton1,4, Cindy V. Looy5 and Dan S. Chaney1 1NMNH Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, United States; 2The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, United States; 3Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster, Münster, Germany; 4National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States; 5University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States 1. INTRODUCTION 1985; Broutin, 1986; Popa, 1999; Steyer et al., 2000; Wagner and Mayoral, 2007; Bercovici and Broutin, 2008; Since 1989, field parties supported by the U.S. National Barthel, 2009; Wagner and Álvarez-Vázquez, 2010; Museum of Natural History have obtained large collections Barthel and Brauner, 2015). Furthermore, because this of mainly Permian plant fossils from north central Texas. locality was collected on three occasions over a time period This work was undertaken to study known localities and to of 50 years and by different parties, comparative analysis of find new fossiliferous deposits that would contribute to a the Sanzenbacher collections provides a basis for assessing better understanding of floral and paleoenvironmental sites that have comparable histories. changes within the region during the early Permian. From the outset, the effort was interdisciplinary and grew, through the contributions of nearly 20 paleobotanists, 2. GEOLOGY palynologists, invertebrate and vertebrate paleontologists, Clay County is the only county in the Permo-Carboniferous and sedimentary geologists of several subdisciplines, to be outcrop belt of north central Texas that lacks marine rocks. quite comprehensive. Our reporting of results, however, has These alluvial sediments accumulated east of a broad been influenced by unexpected developments, including the coastal plain that bordered the Eastern Shelf of the Midland discovery of new plant-fossil assemblages in areas once Basin. -

A Comparative Study of Lady Ferns and Japanese Painted Ferns (Athyrium Spp.)

Plant Evaluation Notes Issue 39, 2015 A Comparative Study of Lady Ferns and Japanese Painted Ferns (Athyrium spp.) Richard G. Hawke, Plant Evaluation Manager and Associate Scientist Photo by Richard Hawke Athyrium filix-femina Lady ferns and Japanese painted ferns of the wood fern family (Dryopteridaceae) Japanese painted ferns has spawned an (Athyrium spp.) are among the most elegant and just a few of the nearly 200 species array of new colorful cultivars as well as a yet utilitarian plants for the shade garden. native to temperate and tropical regions few exceptional hybrids with the common Their lacy fronds arch and twist in a graceful worldwide. The common lady fern lady fern. manner, being both structural and ethereal (A. filix-femina) is a circumglobal species at the same time. Ferns stand on their found in moist woodlands, meadows, While common botanical terms such as foliar merits alone, having no flowers to and ravines throughout North America, leaf, stem, and midrib can be used to overshadow their feathery foliage. The lush Europe, and Asia, and is represented in describe fern foliage, specialized terminology green fronds of lady ferns are in marked gardens by a plethora of cultivars—many of further defines fern morphology. The fern contrast to the sage green, silver, and the oldest forms originated in England leaf or frond is composed of the stipe burgundy tones of the colorful Japanese during the Victorian era. Eared lady fern (stem), blade (leaf), rachis (midrib), and painted ferns. The delicate quality of their (A. otophorum) and Japanese lady fern pinna (leaflet). Crosier or fiddlehead fronds belies their stoutness—they are (A. -

Origin of the Hawaiian Rainforest and Its Transition States in Long-Term

EGU Journal Logos (RGB) Open Access Open Access Open Access Advances in Annales Nonlinear Processes Geosciences Geophysicae in Geophysics Open Access Open Access Natural Hazards Natural Hazards and Earth System and Earth System Sciences Sciences Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Chemistry Chemistry and Physics and Physics Discussions Open Access Open Access Atmospheric Atmospheric Measurement Measurement Techniques Techniques Discussions Open Access Biogeosciences, 10, 5171–5182, 2013 Open Access www.biogeosciences.net/10/5171/2013/ Biogeosciences doi:10.5194/bg-10-5171-2013 Biogeosciences Discussions © Author(s) 2013. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Open Access Open Access Climate Climate of the Past of the Past Discussions Origin of the Hawaiian rainforest and its transition states in Open Access Open Access long-term primary succession Earth System Earth System Dynamics 1 2 Dynamics D. Mueller-Dombois and H. J. Boehmer Discussions 1University of Hawaii at Manoa, Department of Botany, 3190 Maile Way, Honolulu, HI 96822, USA 2Technical University of Munich, Department of Ecology and Ecosystem Management, Chair for Strategic Landscape Open Access Open Access Planning and Management, Emil-Ramann-Strasse 6, 85350 Freising-Weihenstephan, GermanyGeoscientific Geoscientific Instrumentation Instrumentation Correspondence to: D. Mueller-Dombois ([email protected]) Methods and Methods and Received: 31 December 2012 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 11 February 2013 Data Systems Data Systems Revised: 3 June 2013 – Accepted: 21 June 2013 – Published: 30 July 2013 Discussions Open Access Open Access Geoscientific Geoscientific Abstract. This paper addresses the question of transition redeveloping in the more dissected landscapes of the older is- Model Development states in the Hawaiian rainforest ecosystem with emphasis lands loses stature,Model often Development forming large gaps that are invaded on their initial developments. -

Ferns: the Final Frond-Tier in Plant Model Systems

Ferns: The Final Frond-tier in Plant Model Systems Authors: Alaina R. Petlewski, and Fay-Wei Li Source: American Fern Journal, 109(3) : 192-211 Published By: The American Fern Society URL: https://doi.org/10.1640/0002-8444-109.3.192 BioOne Complete (complete.BioOne.org) is a full-text database of 200 subscribed and open-access titles in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Complete website, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/terms-of-use. Usage of BioOne Complete content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Downloaded From: https://bioone.org/journals/American-Fern-Journal on 15 Oct 2019 Terms of Use: https://bioone.org/terms-of-use Access provided by Cornell University American Fern Journal 109(3):192–211 (2019) Published on 16 September 2019 Ferns: The Final Frond-tier in Plant Model Systems 1,2 1,2 ALAINA R. PETLEWSKI AND FAY-WEI LI * 1 Boyce Thompson Institute, Ithaca, New York, USA 14853 ORCID: 0000-0003-4516-1214, 0000-0002-0076-0152 2 Plant Biology Section, Cornell University, New York, USA 14853 Email: 1 [email protected], 2 fl[email protected] ABSTRACT.—Ferns are one of the most speciose lineages of land plants, and occupy an important phylogenetic position sister to seed plants. -

Inventorying the Tree Fern Genus Cibotium of Sumatra: Ecology, Population Size and Distribution in North Sumatra

BIODIVERSITAS ISSN: 1412-033X (printed edition) Volume 12, Number 4, October 2011 ISSN: 2085-4722 (electronic) Pages: 204-211 DOI: 10.13057/biodiv/d120404 Inventorying the tree fern Genus Cibotium of Sumatra: Ecology, population size and distribution in North Sumatra TITIEN NGATINEM PRAPTOSUWIRYO♥, DIDIT OKTA PRIBADI, DWI MURTI PUSPITANINGTYAS, SRI HARTINI Center for Plant Conservation-Bogor Botanical Gardens, Indonesian Institute of Sciences. Jl. Ir. H.Juanda No. 13, P.O. Box 309 Bogor 16003, Indonesia. Tel. +62-251-8322187. Fax. +62-251- 8322187. ♥e-mail: [email protected] Manuscript received: 26 June 2011. Revision accepted: 18 August 2011. ABSTRACT Praptosuwiryo TNg, Pribadi DO, Puspitaningtyas DM, Hartini S (2011) Inventorying the tree fern Genus Cibotium of Sumatra: Ecology, population size and distribution in North Sumatra. Biodiversitas 12: 204-211. Cibotium is one tree fern belongs to the family Cibotiaceae which is easily differentiated from the other genus by the long slender golden yellowish-brown smooth hairs covered its rhizome and basal stipe with marginal sori at the ends of veins protected by two indusia forming a small cup round the receptacle of the sorus. It has been recognized as material for both traditional and modern medicines in China, Europe, Japan and Southeast Asia. Population of Cibotium species in several countries has decreased rapidly because of over exploitation and there is no artificial cultivation until now. The aims of this study were: (i) To re-inventory the species of Cibotiun in North Sumatra, (ii) to record the ecology and distribution of each species, and (iii) to assess the population size of each species.