Lesson 6: Plant Reproduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

History Department Botany

THE HISTORY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY 1889-1989 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA SHERI L. BARTLETT I - ._-------------------- THE HISTORY OF THE DEPARTMENT OF BOTANY 1889-1989 UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA SHERI L. BARTLETT TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface 1-11 Chapter One: 1889-1916 1-18 Chapter Two: 1917-1935 19-38 Chapter Three: 1936-1954 39-58 Chapter Four: 1955-1973 59-75 Epilogue 76-82 Appendix 83-92 Bibliography 93-94 -------------------------------------- Preface (formerly the College of Science, Literature and the Arts), the College of Agriculture, or The history that follows is the result some other area. Eventually these questions of months ofresearch into the lives and work were resolved in 1965 when the Department of the Botany Department's faculty members joined the newly established College of and administrators. The one-hundred year Biological Sciences (CBS). In 1988, The overview focuses on the Department as a Department of Botany was renamed the whole, and the decisions that Department Department of Plant Biology, and Irwin leaders made to move the field of botany at Rubenstein from the Department of Genetics the University of Minnesota forward in a and Cell Biology became Plant Biology's dynamic and purposeful manner. However, new head. The Department now has this is not an effort to prove that the administrative ties to both the College of Department's history was linear, moving Biological Sciences and the College of forward in a pre-determined, organized Agriculture. fashion at every moment. Rather I have I have tried to recognize the attempted to demonstrate the complexities of accomplishments and individuality of the the personalities and situations that shaped Botany Department's faculty while striving to the growth ofthe Department and made it the describe the Department as one entity. -

Plant Reproduction Angiosperm Specific Adaptations Angiosperms

4/15/2013 Gymnosperms Angiosperms Pterophytes Seeds Plant Reproduction Lycophytes Bryophytes Vascular tissue Green algae: BI 103 Plant-Animal A&P Chlorophytes Turn in Homework #1 Land plants Angiosperm specific adaptations • Unlike other plants they have: Why do plants have flowers? In – Flowers other words, what are the – Double fertilization advantages of flowering? – Fruit Discuss this question in groups Alternating Generations In more advanced plants, the sporophyte generation is Angiosperms: the Flowering plants dominant. Why do plants have flowers? Enlists partnerships with insects and other animals Less inbreeding Higher probability the pollen will reach the right plant They don’t have to produce as much pollen 1 4/15/2013 How is pollen an adaptation to land? Alternation of generations modified Allows fertilization to occur even in the absence • Pollen= Male gametophyte of available water. Contains sperm • Ovule= Female gametophyte water Contains egg Moss fertilization Pollen grains Anthers with microspores Microspore to pollen 1. The microspores divides by mitosis to produce two cells Generative cell (1n) Tube cell== vegetative nucleus (1n) 2. A two layered wall develops around the microspore to become the pollen 3. The generative cell undergoes division once more 3n total (3 nuclei) in pollen Double fertilization Fruit development 1. Two pollen nuclei enter ovule 2. One fuses with the egg to form the zygote 3. The other fuses with 2 central cell nuclei to become the endosperm (3n), food for the zygote Becomes the seed! Becomes -

Floral Symmetry Affects Speciation Rates in Angiosperms Risa D

Received 25 July 2003 Accepted 13 November 2003 Published online 16 February 2004 Floral symmetry affects speciation rates in angiosperms Risa D. Sargent Department of Zoology, University of British Columbia, 6270 University Boulevard, Vancouver, British Columbia V6T 1Z4, Canada ([email protected]) Despite much recent activity in the field of pollination biology, the extent to which animal pollinators drive the formation of new angiosperm species remains unresolved. One problem has been identifying floral adaptations that promote reproductive isolation. The evolution of a bilaterally symmetrical corolla restricts the direction of approach and movement of pollinators on and between flowers. Restricting pollin- ators to approaching a flower from a single direction facilitates specific placement of pollen on the pollin- ator. When coupled with pollinator constancy, precise pollen placement can increase the probability that pollen grains reach a compatible stigma. This has the potential to generate reproductive isolation between species, because mutations that cause changes in the placement of pollen on the pollinator may decrease gene flow between incipient species. I predict that animal-pollinated lineages that possess bilaterally sym- metrical flowers should have higher speciation rates than lineages possessing radially symmetrical flowers. Using sister-group comparisons I demonstrate that bilaterally symmetric lineages tend to be more species rich than their radially symmetrical sister lineages. This study supports an important role for pollinator- mediated speciation and demonstrates that floral morphology plays a key role in angiosperm speciation. Keywords: reproductive isolation; pollination; sister group comparison; zygomorphy 1. INTRODUCTION The importance of pollinator-mediated selection in angiosperms is well supported by theory (Kiester et al. -

Pollen Tube Guidance by Pistils Ensures Successful Double Fertilization Ravishankar Palanivelu∗ and Tatsuya Tsukamoto

Advanced Review Pathfinding in angiosperm reproduction: pollen tube guidance by pistils ensures successful double fertilization Ravishankar Palanivelu∗ and Tatsuya Tsukamoto Sexual reproduction in flowering plants is unique in multiple ways. Distinct multicellular gametophytes contain either a pair of immotile, haploid male gametes (sperm cells) or a pair of female gametes (haploid egg cell and homodiploid central cell). After pollination, the pollen tube, a cellular extension of the male gametophyte, transports both male gametes at its growing tip and delivers them to the female gametes to affect double fertilization. The pollen tube travels a long path and sustains its growth over a considerable amount of time in the female reproductive organ (pistil) before it reaches the ovule, which houses the female gametophyte. The pistil facilitates the pollen tube’s journey by providing multiple, stage-specific, nutritional, and guidance cues along its path. The pollen tube interacts with seven different pistil cell types prior to completing its journey. Consequently, the pollen tube has a dynamic gene expression program allowing it to continuously reset and be receptive to multiple pistil signals as it migrates through the pistil. Here, we review the studies, including several significant recent advances, that led to a better understanding of the multitude of cues generated by the pistil tissues to assist the pollen tube in delivering the sperm cells to the female gametophyte. We also highlight the outstanding questions, draw attention to opportunities created by recent advances and point to approaches that could be undertaken to unravel the molecular mechanisms underlying pollen tube–pistil interactions. 2011 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. -

Ap09 Biology Form B Q2

AP® BIOLOGY 2009 SCORING GUIDELINES (Form B) Question 2 Discuss the patterns of sexual reproduction in plants. Compare and contrast reproduction in nonvascular plants with that in flowering plants. Include the following topics in your discussion: (a) alternation of generations (b) mechanisms that bring female and male gametes together (c) mechanisms that disperse offspring to new locations Four points per part. Student must write about all three parts for full credit. Within each part it is possible to get points for comparing and contrasting. Also, specific points are available from details provided about nonvascular and flowering plants. Discuss the patterns of sexual reproduction in plants (4 points maximum): (a) Alternation of generations (4 points maximum): Topic Description (1 point each) Alternating generations Haploid stage and diploid stage. Gametophyte Haploid-producing gametes. Dominant in nonvascular plants. Double fertilization in flowering plants. Gametangia; archegonia and antheridia in nonvascular plants. Sporophyte Diploid-producing spores. Heterosporous in flowering plants. Flowering plants produce seeds; nonvascular plants do not. Flowering plants produce flower structures. Sporangia (megasporangia and microsporangia). Dominant in flowering plants. (b) Mechanisms that bring female and male gametes together (4 points maximum): Nonvascular Plants (1 point each) Flowering Plants (1 point each) Aquatic—requires water for motile sperm Terrestrial—pollination by wind, water, or animal Micropyle in ovule for pollen tube to enter Pollen tube to carry sperm nuclei Self- or cross-pollination Antheridia produce sperm Gametophytes; no antheridia or archegonia Archegonia produce egg Ovules produce female gametophytes/gametes Pollen: male gametophyte that produces gametes © 2009 The College Board. All rights reserved. Visit the College Board on the Web: www.collegeboard.com. -

Plant Reproduction | Topic Notes

Plant Reproduction | Topic Notes Sexual reproduction is the fusion of male and female gametes to produce a diploid zygote. (The new individual is genetically different from both parents). Advantages include genetic variation, reduced competition (between parent & offspring) and good chance of surviving harsh winter. A disadvantage is that there’s a long period of growth required. Structure of flowering plant: Megaspore (egg) formation & microspore (pollen) formation: The carpel (female part of the flower) is composed of the stigma (sticky to trap pollen grains), style (supports stigma in best position to trap pollen grains) and ovary (contains 1 or more ovules which following fertilisation will develop into seeds). The stamen (male part of the flower) is composed of the anther (produces pollen grains) and filament (supports anther in best position to transport pollen grains). Sepals support the developing flower before it blooms. Petals may be bright coloured in insect pollinated plants (to attract them). The receptacle is the organ from which the flower develops and functions in supporting it. Pollination is the transfer of pollen from the anther to the stigma of a flower of the same species. It may be: 1. Self-pollination: the transfer of pollen from the anther to the stigma in the same plant. 2. Cross-pollination: the transfer of pollen from the anther to the stigma of a different plant but of the same species. 1 Plant Reproduction | Topic Notes Fertilisation is the union of a haploid male gamete with a haploid female gamete, to produce a diploid zygote. Once a pollen grain has landed on the stigma, the tube nucleus moves down through the stigma and style forming a pollen tube and enters the ovule at the micropyle, guided towards the egg by chemotropism, the tube nucleus then degenerates. -

Plant Diversity Unique Plant Adaptations Alternation Of

8/9/2010 Land plants Origins Shared ancestor with green algae. Plant Diversity Researchers have identified green algae called charophyceans as the closest The Evolution of the relatives of land plants Photosynthetic Terrestrial Plants Unique Plant Adaptations First true land plants were short Adaptations for a terrestrial existence and required water for reproduction 1) Roots --anchoranchor the plant and absorb water & nutrients from the soil. 2) Cuticle ––aa waxy coating to prevent drying out 3) Stomata ––porespores in the leaves and stems that allow for gas exchange. 4) Conducting vessels ––forfor transport of water , minerals, and sugars through the plant body. 5) Lignin --StiffeningStiffening and support of stems. 6) Unique reproductive structures e.g. pollen –– for transporting gametes. Alternating Generations Alternation of Generations In more advanced plants sporophyte generation dominant. The alternating life cycle of plants that involves changes between a: 1)Sporophyte generation AND………. 2) G ametophyte generation 1 8/9/2010 Mosses & nonvascular plants have life Contrasting the Generations cycles dominated by gametophytes Hairy-cap moss Sporophyte Gametophyte Diploid state (double set Haploid state (half the Brown Capsule of chromosomes in cells –– amount of chromosomes full set) in cells) Sporophyte Produces seeds in seed Produces the gametes bearing plants i.e. (sperm & egg). Makes spores Predominant form in Gametophyte Predominant form in mosses & ferns (lower higher plants e.g. trees. plants). (Green & leafy) Characteristics of Mosses Life Cycle of Mosses Division Bryophytes The sporophyte forms on, and is nourished by, the dominant gametophyte Nonvascular (don’t have special methods of conducting water & minerals) ––tendtend to be very small. -

Ferns Robert H

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Illustrated Flora of Illinois Southern Illinois University Press 10-1999 Ferns Robert H. Mohlenbrock Southern Illinois University Carbondale Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois Part of the Botany Commons Recommended Citation Mohlenbrock, Robert H., "Ferns" (1999). Illustrated Flora of Illinois. 3. http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/siupress_flora_of_illinois/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Southern Illinois University Press at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Illustrated Flora of Illinois by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS ROBERT H. MOHLENBROCK, General Editor THE ILLUSTRATED FLORA OF ILLINOIS s Second Edition Robert H. Mohlenbrock SOUTHERN ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY PRESS Carbondale and Edwardsville COPYRIGHT© 1967 by Southern Illinois University Press SECOND EDITION COPYRIGHT © 1999 by the Board of Trustees, Southern Illinois University All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America 02 01 00 99 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Mohlenbrock, Robert H., 1931- Ferns I Robert H. Mohlenbrock. - 2nd ed. p. em.- (The illustrated flora of Illinois) Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Ferns-Illinois-Identification. 2. Ferns-Illinois-Pictorial works. 3. Ferns-Illinois-Geographical distribution-Maps. 4. Botanical illustration. I. Title. II. Series. QK525.5.I4M6 1999 587'.3'09773-dc21 99-17308 ISBN 0-8093-2255-2 (cloth: alk. paper) CIP The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.§ This book is dedicated to Miss E. -

NAPPC Pollinator Curriculum

NAPPC Pollinator Curriculum >>next Nature's Partners: Pollinators, Plants, and You | Copyright 2007 The Pollinator Partnership Please help us improve and expand this resource! Send us your comments, questions, and suggestions. Let us know how you are using the curriculum, what works well, and what challenges you're encountering. E-mail: [email protected] http://www.nappc.org/curriculum/9/25/2007 11:10:30 AM NAPPC Pollinator Curriculum Printer-Friendly View | Normal View Why Care About Pollinators? Many people think only of allergies when they hear Nature's Partners is an the word pollen. But pollination — the transfer of inquiry learning-based pollen grains to fertilize the seed-producing ovaries curriculum for young of flowers — is an essential part of a healthy people in the 3rd through ecosystem. Pollinators play a significant role in the Home the 6th grade. production of over 150 food crops in the United >>Learn more about the curriculum. States — among them apples, alfalfa, almonds, Why Care About blueberries, cranberries, kiwis, melons, pears, Pollinators? plums, and squash. Scientific Thinking Bees, both managed honey bees and native bees, Processes are the primary pollinators. However, more than 100,000 invertebrate species, including bees, moths, butterflies, beetles, and flies, serve as pollinators — Implementing the as well as 1,035 species of vertebrates, including Curriculum birds, mammals, and reptiles. In the United States, the annual benefit of managed honey bees to Assessment consumers is estimated at $14.6 billion. The services provided by native pollinators further contribute to Outline the productivity of crops as well as to the survival and reproduction of many native plants. -

Two Expansin Genes, Atexpa4 and Atexpb5, Are Redundantly Required for Pollen Tube Growth and Atexpa4 Is Involved in Primary Root Elongation in Arabidopsis Thaliana

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article Two Expansin Genes, AtEXPA4 and AtEXPB5, Are Redundantly Required for Pollen Tube Growth and AtEXPA4 Is Involved in Primary Root Elongation in Arabidopsis thaliana Weimiao Liu 1,2, Liai Xu 1,2 , Hui Lin 3 and Jiashu Cao 1,2,4,* 1 Laboratory of Cell and Molecular Biology, Institute of Vegetable Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China; [email protected] (W.L.); [email protected] (L.X.) 2 Key Laboratory of Horticultural Plant Growth, Development and Quality Improvement, Ministry of Agriculture, Hangzhou 310058, China 3 Crop Research Institute, Fujian Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Fuzhou 350013, China; [email protected] 4 Zhejiang Provincial Key Laboratory of Horticultural Plant Integrative Biology, Hangzhou 310058, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-131-8501-1958 Abstract: The growth of plant cells is inseparable from relaxation and expansion of cell walls. Expansins are a class of cell wall binding proteins, which play important roles in the relaxation of cell walls. Although there are many members in expansin gene family, the functions of most expansin genes in plant growth and development are still poorly understood. In this study, the functions of two expansin genes, AtEXPA4 and AtEXPB5 were characterized in Arabidopsis thaliana. AtEXPA4 and AtEXPB5 displayed consistent expression patterns in mature pollen grains and pollen tubes, but AtEXPA4 also showed a high expression level in primary roots. Two single mutants, atexpa4 and atexpb5, showed normal reproductive development, whereas atexpa4 atexpb5 double mutant was defective in pollen tube growth. Moreover, AtEXPA4 overexpression enhanced primary root Citation: Liu, W.; Xu, L.; Lin, H.; Cao, elongation, on the contrary, knocking out AtEXPA4 made the growth of primary root slower. -

Go on a Backyard Botany Hunt

Go on a Backyard Botany Hunt Want to give your child a lesson on the wide world of plants? You don't have to go camping! You've got an amazing array of wonderful plants right in your backyard or local park. To get your child started, here's a fun activity that will have him researching, collecting, and charting plant specimens from the neighborhood. Just be prepared for a little dirt under his fingernails! What You Need: Large sheet of poster board Marker or pen Ruler Tape or push pins 10 sandwich bags Field guide or Internet access Digital camera (optional) What You Do: Specimen Name Description Habitat Notes Plant 1 Plant 2 Plant 3 Plant 4 Plant 5 Plant 6 Plant 7 Plant 8 Plant 9 Plant 10 1. Step 1 Before your child can embark on his botany hunt, he'll need to do a little research into the types of plants that are growing all around him. There are many ways to get the goods, but getting an illustrated field guide for your area from the library or bookstore is probably the best. Short of that, Internet research into the plants in your area should yield useful information and images. 2. Step 2 Get out in the garden! If you don't have access to a backyard, take a trip to a nearby park or nature area – anywhere plants can be found. Have your field guide with you to research and identify the plants that you see, and take photographs of the plants in their natural habitat. -

The Ferns and Their Relatives (Lycophytes)

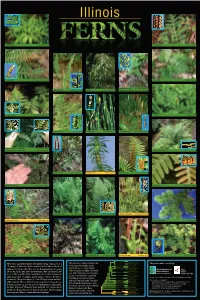

N M D R maidenhair fern Adiantum pedatum sensitive fern Onoclea sensibilis N D N N D D Christmas fern Polystichum acrostichoides bracken fern Pteridium aquilinum N D P P rattlesnake fern (top) Botrychium virginianum ebony spleenwort Asplenium platyneuron walking fern Asplenium rhizophyllum bronze grapefern (bottom) B. dissectum v. obliquum N N D D N N N R D D broad beech fern Phegopteris hexagonoptera royal fern Osmunda regalis N D N D common woodsia Woodsia obtusa scouring rush Equisetum hyemale adder’s tongue fern Ophioglossum vulgatum P P P P N D M R spinulose wood fern (left & inset) Dryopteris carthusiana marginal shield fern (right & inset) Dryopteris marginalis narrow-leaved glade fern Diplazium pycnocarpon M R N N D D purple cliff brake Pellaea atropurpurea shining fir moss Huperzia lucidula cinnamon fern Osmunda cinnamomea M R N M D R Appalachian filmy fern Trichomanes boschianum rock polypody Polypodium virginianum T N J D eastern marsh fern Thelypteris palustris silvery glade fern Deparia acrostichoides southern running pine Diphasiastrum digitatum T N J D T T black-footed quillwort Isoëtes melanopoda J Mexican mosquito fern Azolla mexicana J M R N N P P D D northern lady fern Athyrium felix-femina slender lip fern Cheilanthes feei net-veined chain fern Woodwardia areolata meadow spike moss Selaginella apoda water clover Marsilea quadrifolia Polypodiaceae Polypodium virginanum Dryopteris carthusiana he ferns and their relatives (lycophytes) living today give us a is tree shows a current concept of the Dryopteridaceae Dryopteris marginalis is poster made possible by: { Polystichum acrostichoides T evolutionary relationships among Onocleaceae Onoclea sensibilis glimpse of what the earth’s vegetation looked like hundreds of Blechnaceae Woodwardia areolata Illinois fern ( green ) and lycophyte Thelypteridaceae Phegopteris hexagonoptera millions of years ago when they were the dominant plants.