Laws and Regulations Affecting the Powers of Chiefs in the Natal and Zululand Regions, 1875-1910: a Historical Examination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

1. a Confession1 2. Speech at Alfred High School, Rajkot3

1. A CONFESSION1 [1884] I wrote it on a slip of paper and handed it to him myself. In this note not only did I confess my guilt, but I asked adequate punishment for it, and closed with a request to him not to punish himself for my offence. I also pledged myself never to steal in future.2 An Autobiography, Pt. I, Ch. VIII 2. SPEECH AT ALFRED HIGH SCHOOL, RAJKOT 3 July 4, 1888 I hope that some of you will follow in my footsteps, and after you return from England you will work wholeheartedly for big reforms in India. [From Gujarati] Kethiawar Times, 12-7-1888 1 When Gandhiji was 15, he had removed a bit of gold from his brother’s armlet to clear a small debt of the latter. He felt so mortified about his act that he decided to make a confession to his father. Parental forgiveness was granted to him in the form of silent tears. The incident left a lasting mark on his mind. In his own words, it was an object-lesson to him in the power of ahimsa. The original not being available; his own report of it, as found in An Autobiography, is reproduced here. 2 According to Mahatma Gandhi : The Early Phase, p. 212, one of the senten- ces in the confession was : “So, father, your son is now, in your eyes, no better than a common thief.” 3 Gandhiji was given a send-off by his fellow-students of the Alfred High School, Rajkot, when he was leaving for England to study for the Bar. -

1. Letter to M. M. Bhownaggree1

1. LETTER TO M. M. BHOWNAGGREE1 25 & 26 COURT CHAMBERS, RISSIK STREET, JOHANNESBURG, May 23, 1904 TO SIR MANCHERJEE BHOWNAGGREE, M.P. 196 CROMWELL ROAD LONDON, ENGLAND DEAR SIR, His Excellency the Lieutenant-Governor, Sir Arthur Lawley, while passing through Heidelberg, in reply to an Indian deputation which presented His Excellency last week with an address,2 said in effect that the liberty of the Indian to trade unrestricted in virtue of the decision in the test case will not be tolerated and that Mr. Lyttelton has already been approached with a view to sanctioning legislation in the desired direction. The position of the Indian as defined in Law 3 of 1885 as ame- nded in 1886 and interpreted in the light of the test case is this: (1) An Indian can immigrate into the Colony without restric- tion. (2) He can trade anywhere he likes in the Colony. Locations may be set apart for him but the law cannot force him to reside only in Locations, as there is no sanction provided in the law for it. (3) He cannot become a burgher. (4) He cannot own landed property except in Locations. (5) He must pay a registration fee of £3 on entering the Colony. With the exception, therefore, of the prohibition as to holding landed property, even in virtue of the above law the condition of the Indian is now not altogether precarious. Freedom to immigrate, however, has been almost absolutely taken away by making what is, after all, an unjust use of the Peace 1 A copy of the letter was forwarded to the Colonial Office by Bhownaggree. -

El Departament D'agricultura a Zimbabwe

EL DEPARTAMENT D’AGRICULTURA A ZIMBABWE (1897-1914): FEBLESES, CONFLICTES I CONTRADICCIONS EN LA CONSTRUCCIÓ DE L’ESTAT COLONIAL Tesi doctoral presentada per optar al títol de Doctor en Història Contemporània. Autor: Eduard Gargallo i Sariol Universitat de Barcelona. Octubre de 2006. Departament: Història Contemporània. Programa: Societat i cultura al món contemporani. Bienni: 1995-1997. Director: Dr. Ferran Iniesta i Vernet. Tutor: Dr. Ramon Casteràs i Archidona. FONTS I BIBLIOGRAFIA 669 670 FONTS I BIBLIOGRAFIA ARXIUS National Archives of Zimbabwe (NAZ) Department of Agriculture G 1/1/1/1 G 1/3/2/5 G 1/6/4/1 G 1/8/1/11 G 1/1/2 G 1/3/2/8 G 1/6/4/3 G 1/8/3/2 G 1/1/4 G 1/3/2/24 G 1/6/4/4 G 1/8/3/3 G 1/2/1 G 1/5/1 G 1/8/1/3 G1/9/1 G 1/3/1/2 G 1/5/2/4 G 1/8/1/5 G 1/3/2/1 G 1/5/3 G 1/8/1/9 Forestry Branch GF 2/1/1 GF 2/1/2 GF 2/1/6 GF 3/2/1 GF 3/2/2 Veterinary Department V 1/1/3 V 1/2/12/2 V 1/2/1/2 V 1/7/1 V 1/2/6/2 V 1/10/9/1 V 1/2/10 V 3/3/1/1 Administrator's Office A 3/2/1 A 3/25/1 A 3/25/3 Vol 2. -

A Cross-Generational Study of the Perception and Construction of South Africans of Indian Descent As Foreigners by Fellow Citizens

A CROSS-GENERATIONAL STUDY OF THE PERCEPTION AND CONSTRUCTION OF SOUTH AFRICANS OF INDIAN DESCENT AS FOREIGNERS BY FELLOW CITIZENS Kathryn Pillay Supervisor: Gerhard Maré Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Social Sciences, College of Humanities, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College Campus, Durban, South Africa. DECLARATION I, Kathryn Pillay, declare that the research reported on in this thesis, except where otherwise indicated, is my own original research. Where data, ideas and quotations have been used that are not my own they have been duly acknowledged as being sourced from other persons. No part of this work has been submitted for any other degree or examination at any other university. Signature: ______________ Date: ______________ Kathryn Pillay (Candidate) i _____________________________________________________________ For Alexa May you dream bigger dreams and reach higher heights, always remembering that “ … God, who by his mighty power at work within us is able to do far more than we would ever dare to ask or even dream of - infinitely beyond our highest prayers, desires, thoughts, or hopes” (Ephesians 3:20).This thesis is a testament to that wonderful promise. ______________________________________________________________ I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to Prof. Gerry Maré, my supervisor, mentor and friend. Thank you for generously imparting your knowledge and expertise to me. Under your tutelage I have developed and grown as an academic. I will be forever grateful for all the support, advice, and encouragement that you offered to me throughout this process, and most importantly, for your unwavering belief in me. -

1 Chapter 1 Afrikaners in Natal Up

University of Pretoria etd – Wassermann, J M (2005) 1 CHAPTER 1 AFRIKANERS IN NATAL UP TO THE OUTBREAK OF THE ANGLO-BOER WAR: EXPERIENCES AND ATTITUDES PREVALENT AT THE TIME By the late 1870s, Natal constituted the only European political entity in South Africa in which Afrikaners formed a minority group amongst the white inhabitants. This community was shaped by events spanning half a century which included: living under British rule in the Cape Colony, embarking on the Great Trek, experiencing strained relations and subsequent military engagements with the Zulu, marked especially by the Battle of Blood River on 16 December 1838, witnessing the creation of the Republic of Natalia and its subsequent annexation and destruction by the British after the Battle of Congella in 1843.1 The cycle was completed when Colonial rule was instituted in 18452 and the subsequent attempt in1847 by Natal Afrikaners to resurrect a republic, the Republic of Klip River, failed.3 The Afrikaners who remained in Natal throughout these events increased in number as immigrants from the Cape Colony joined them,4 and slowly evolved into a united community, trapped in an agrarian economy.5 Their socio-political world was characterised by complaints of preferential treatment afforded to Africans, and a lack of access to land. A predominant sense of injustice prevailed, exemplified by acts such as the execution of Hans Dons de Lange,6 and the community experienced a general feeling of disempowerment and unfair treatment under British rule. They had no voice to express their feelings of dissatisfaction since Dutch newspapers had not proved profitable,7 Dutch had become a marginalised language,8 and the Nederduits Gereformeerde Kerk or Dutch Reformed Church (hereafter DRC) which was caught up in a constant struggle for survival, both financially and in terms of recruiting members, lacked power.9 As a result, by the early 1870s, the Boshof(f) brothers, JN and JC, were the only Afrikaner members of the Natal Legislative 1. -

Notes and References

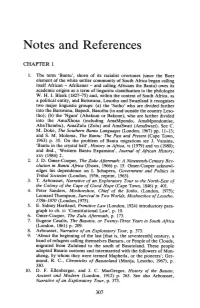

Notes and References CHAPTER 1 1. The term 'Bantu', shorn of its racialist overtones (since the Boer element of the white settler community of South Africa began calling itself African- Afrikaner- and calling Africans the Bantu) owes its academic origins as a term of linguistic classification to the philologist W. H. I. Bleek (1827-75) and, within the context of South Africa, as a political entity, and Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland it recognises two major linguistic groups: (a) the 'Sotho' who are divided further into the Batswana, Bapedi, Basotho (in and outside the country Leso tho); (b) the 'Nguni' (Abakuni or Bakone), who are further divided into the AmaXhosa (including AmaMpondo, AmaMpondomise, AbaThembu), AmaZulu (Zulu) and AmaSwati (AmaSwazi). See C. M. Doke, The Southern Bantu Languages (London, 1967) pp. 11-13; and S. M. Molema, The Bantu: The Past and Present (Cape Town, 1963) p. 35. On the problem of Bantu migrations see J. Vansina, 'Bantu in the crystal ball', History in Africa, VI (1979) and VII (1980); and ibid., 'Western Bantu Expansion', Journal of African History, XXV (1984) 2. 2. J.D. Omer-Cooper, The Zulu Aftermath: A Nineteenth-Century Rev olution in Bantu Africa (Essex, 1966) p. 15. Omer-Cooper acknowl edges his dependence on I. Schapera, Government and Politics in Tribal Societies (London, 1956, reprint, 1963). 3. T. Arbousset, Narrative of an Exploratory Tour to the North-East of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope (Cape Town, 1846) p. 401. 4. Peter Sanders, Moshoeshoe, Chief of the Sotho, (London, 1975); Leonard Thompson, Survival in Two Worlds, Moshoeshoe of Lesotho, 178(r..J870 (London,1975). -

AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY: the STORY of MY EXPERIMENTS with TRUTH by Mohandas K

1 AN AUTOBIOGRAPHY: THE STORY OF MY EXPERIMENTS WITH TRUTH by Mohandas K. Gandhi EDITOR'S INTRODUCTION The first edition of Danghiji's Autobiography was published in two volumes, Vol. I in 1927 and Vol. II in 1929. The original in Gujarati which was priced at Re. 1/- has run through five editions, nearly 50,000 copies having been sold. The price of the English translation (only issued in library edition) was prohibitive for the Indian reader, and a cheap edition has long been needed. It is now being issued in one volume. The translation, as it appeared serially in Young India , had, it may be noted, the benefit of Gandhiji's revision. It has now undergone careful revision, and from the point of view of language, it has had the benefit of careful revision by a revered friend, who, among many other things, has the reputation of being an eminent English scholar. Before undertaking the task, he made it a condition that his name should on no account be given out. I accept the condition. It is needless to say it heightens my sense of gratitude to him. Chapters XXIX-XLIII of Part V were translated by my friend and colleague Pyarelal during my absence in Bardoli at the time of the Bardoli Agrarian Inquiry by the Broomfield Committee in 1928-29. MAHADEV DESAI 1940 2 INTRODUCTION Four or five years ago, at the instance of some of my nearest co-workers, I agreed to write my autobiography. I made the start, but scarcely had I turned over the first sheet when riots broke out in Bombay and the work remained at a standstill. -

The Basuto Rebellion, Civil War and Reconstruction, 1880-1884

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 7-1-1973 The Basuto rebellion, civil war and reconstruction, 1880-1884 Douglas Gene Kagan University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Kagan, Douglas Gene, "The Basuto rebellion, civil war and reconstruction, 1880-1884" (1973). Student Work. 441. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/441 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE BA5UT0 REBELLION, CIVIL WAR, AND RECONSTRUCTION, 1B8O-1804 A Thesis Presented to the Dapartment of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College ‘University of Nebraska at Omaha In Partial Fulfillment if the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Douglas Gene Kagan July 1973 UMI Number: EP73079 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI EP73079 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 t Accepted for the faculty of The Graduate College of the University of Nebraska at Omaha, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Art3. -

A REPORT Oo the Emigrants Repatriated to India Under the Assisted Emigration Scheme From

A REPORT Oo the Emigrants Repatriated to India under the Assisted Emigration Scheme from. South Africa and Oo the Problem of Returned Emigrants from All Colonies. B, BHAWANI DAYAL SANNYASI Bl!NARSIDAS CHATURVl!Dl ( .<ln lnd,,,.nd,nl Knqulry J Im MAY 19J1 ,. P rinted by BllNARSIDAS CHATURVEDl at the_ Prabasi Press 4\ · 120-2. Upper Circular Road Calcutta, India THE PROBLEM Of RETURNED EMIGRANTS MY EXPERIENCES My friend, Swami Bhawani Dayal SannyasJ, qas asked me to write down my personal experiences regardinf the returned emigrants, with ·whose problems I have been associated to a certain extent for some years past. I do so with considerable reluctance as I realise that my knowledge of this problem is only one-sided. I have never had the opportunity of seeing these returning emigrants while they were living in the colonies. So it is not possible for me to make a comparative study of their conditions abrOjld and at home The only man who can deal with this problem quite authoritatively and exhaustively is Mr. C. F. Andrews, who bas been to almost every places, outside India. where Indians have settled in any large number. Unfortunately, Mr. Andrews is away in England and his expert guidance is not available for us at this time. We do not know when Mr. Andrews will return. In the meanwhile, Swami Bhawani Dayal is anxious to publish his report a~ early as possible. It has already been delayed by a year and he cannot afford to wait any longer. Under these circumstances I have to writt out these few pages which may serve as a back-ground to th report of Swami Bhawani Dayal Sannyasi. -

1908 Asiatics Ordinance in Perspective

Seminar: UNIVERSITY OF RHODESIA : DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY HENDERSON SEMINAR NO.27 THE 1908 ASIATICS ORDINANCE IN PERSPECTIVE b y ALI MOHAMED HASSAM KALSHEKER fmm TJe latter half of ^ 19th century witnessed large-scale emigration from the Indian sub-continent to lands across the seas. A large measure of this outpouring spilt itself into eastern and southern Africa. The two a * East Africa ^ South Mrioa. Rhodesia was very much a state in the South African orbit and was deeply influenced by the Indian lnfiUX int° Natal' ^ Transvaal and the Cape Colony. This 19th century S S Uf hwas by any weans o n ly manifestation of India's relationship SJ? seaboard and interior territories of Africa. Evidence of ?Ji3 relationship stretches back to the beginnings of the Christian era and, to a very great extent, concerns the land new called Rhodesia. The evidence consists of sane archaeological material of Indian manufacture unearthed at various sites in Rhodesia. The evidence unravelled so far is not very conclusive but makes for interesting speculation. The most reliable authority for these early Indian links with Rhodesia is Roger Sumners.1 He bases his theories about the Indian connection on his thorough study of ancient mining methods in Rhodesia as well as on a few archaeological discoveries. He argues that the history of ancient mining in Rhodesia has been a record of systematic exploitation? consequently, 'it seems unreasonable to consider ancient Rhodesian mining as having been locally evolved, rather must we expect to look abroad for its origins1.2 -

Historia Volume 26 #2

100 THE BACKGROUND AND THE UNDERLYING CAUSES OF DINUZULU'S SECOND BANISHMENT FROM ZULULAND S.]. Maphalala Dlangezwa High School After Cetshwayo's deposition at the end of the Anglo-Zulu War of 1879 he was allowed to re.turn to Zulu land in 1883. He was, however, to have auti}ority only over a part of Zululand. The other part was given to his British-supported enemy, Zibhebhu. Conse- quently, the ground for unrest was laid because war soon broke out between the Usuthu and the Mandlakazi. The Civil War continued until February 1884, when Cet- shwayo died in a kraal near Eshowe. In an attempt to avenge his father's death and to regain the Usuthu lands taken by the Mandlakazi, Dinuzulu solicited Afrikaner aid. In May 1884, a party of Afrikaners from the Transvaal under Coenraad Meyer recognis- ed Dinuzulu as th~ new king. Consequently, the Usuthu, supported by the Afrikaners, decisively crushed Zibhebu's forces at the Battle of Tshaneni on 5 June 1884. Unfortunately the British authorities were against the revival of the Zulu kingdom, hence the annexation of Zululand in May 1887 and the resettlement of Zibhebhu in the Ndwandwe district giving him virtual free reins to molest Dinuzulu. This was the background to the Usuthu revolt of 1888 which, after an unjust trial, led to the banishment of Dinuzulu and his uncles Ndabuko and Shinganato St. Helena.1 Dinuzulu's second banishment in 1909 can be understood by looking at the con- ditions of his return from St Helena, his reconciliation with Zibhebhu in 1898 and the subsequent reaction from the Minister for Native Affairs in Natal, the succession to the Mandlakazi tribe, and the warning by James Crosby about the Zulu dissatisfaction in 1905.