Ipod Tour: Painting Matters INTRO

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5785 Chapter 2: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Introduction The masters, truth to tell, are judged as much by their influence as by their works. Emile Zola, 18841 Important artists are innovators: they are important because they change the way their successors work. The more widespread, and the more profound, the changes due to the work of any artist, the greater is the importance of that artist. Recognizing the source of artistic importance points to a method of measuring it. Surveys of art history are narratives of the contributions of individual artists. These narratives describe and explain the changes that have occurred over time in artists’ practices. It follows that the importance of an artist can be measured by the attention devoted to his work in these narratives. The most important artists, whose contributions fundamentally change the course of their discipline, cannot be omitted from any such narrative, and their innovations must be analyzed at length; less important artists can either be included or excluded, depending on the length of the specific narrative treatment and the tastes of the author, and if they are included their contributions can be treated more summarily. -

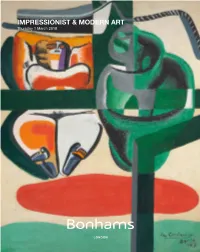

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Calder / Dubuffet Entre Ciel Et Terre Entre Ciel Et Terre © Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images/Hulton Archive © Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis /Preface Foreword

CALDER / DUBUFFET ENTRE CIEL ET TERRE ENTRE CIEL ET TERRE © Evans/Three Lions/Getty Images/Hulton Archive © Pierre Vauthey/Sygma/Corbis /PREFACE FOREWORD/ Opera Gallery Genève est heureuse de présenter une exposition exceptionnelle regroupant des œuvres de deux Opera Gallery Geneva is pleased to present an exceptional exhibition with works by two giants of the 20th century: géants du 20ème siècle : Alexander Calder et Jean Dubuffet. Au premier regard, leurs parcours et œuvres sont bien Alexander Calder and Jean Dubuffet. At first glance, their careers and work are very different, but a lot of elements différents, pourtant beaucoup d’éléments les rapprochent. draw them together. Ces deux artistes sont de la même génération mais ne se sont jamais rencontrés. Alexander Calder était These two artists are from the same generation but never met. Alexander Calder was American and Jean Dubuffet américain et Jean Dubuffet français. les deux ont vécu leurs vies artistiques des deux côtés de l’Atlantique. was French. Both have lived their artists’ lives travelling from one continent to the other. Both have been, at les deux ont été, au début de leurs carrières respectives, considérés comme des “outsiders” dans leurs propres the beginning of their respective careers considered as “outsiders” in their own country but their talent was pays mais leur talent a été immédiatement reconnu en France pour Calder et aux etats-Unis pour Dubuffet. immediately acknowledged in France for Calder and in America for Dubuffet. tous deux ont “révolutionné” l’art dit conventionnel grâce à une utilisation audacieuse de techniques et matériaux Both have revolutionized conventional art by an audacious use of informal techniques and materials. -

JEAN DUBUFFET Brutal Beauty

JEAN DUBUFFET BRutaL beautY JEAN DUBUFFET BRutaL beautY EDITED BY ELEANOR NAIRNE PRESTEL MUNICH • LONDON • NEW YORK CONTENTS FOREWORD 7 MATTER AND MEMORY 11 TRUE FACE 37 BEAUTY AND THE BRUT, ELEANOR NAIRNE 50 LADIES’ BODIES 57 MENTAL LANDSCAPES 71 BEAUTY DEGREE ZERO, KENT MITCHELL MINTURN 80 THE GARDEN 87 PRECARIOUS LIFE 101 STATUES ALSO LIVE: JEAN DUBUFFET’S PRECARIOUS, CREATURELY LIFE, RACHEL E. PERRY 118 TEXTUROLOGY 125 PARIS CIRCUS 137 SCINTILLATING MATTER, SEETHING LIFE: FROM THE ‘TEXTUROLOGIES’ TO ‘PARIS CIRCUS’, SARAH WILSON 144 ART BRUT, 1945 151 THE COLLECTION RETURNS 171 JEAN DUBUFFET: THE ARTIST AND ART BRUT – DEEP-ROOTED RELATIONSHIPS, SARAH LOMBARDI 190 L’HOURLOUPE 197 COUCOU BAZAR 207 THE HIGH SEAS OF L’HOURLOUPE, SOPHIE BERREBI 214 THEATRES OF MEMORY 221 NON-PLACE 235 THE SWALLOW AND THE DAGGER, CAMILLE HOUZÉ 244 CHRONOLOGY, CAMILLE HOUZÉ 251 LIST OF WORKS 270 ENDNOTES 273 AUTHOR BIOGRAPHIES 283 INDEX 284 IMAGE CREDITS 286 6 FOREWORD Jean Dubuffet wrote ‘Notes for the Well-Read’ in 1945, soon after Dubuffet’s experimental drive won him the admiration of an array he devoted himself to becoming an artist.1 The text is made up of of younger artists – from Claes Oldenburg to Paula Rego, David a sequence of exhortations, organized under amusing subtitles Hockney, Eva Hesse, Robert Smithson, Chuck Close, Mike Kelley, that reflect many of the concerns that would captivate him for the Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat. It is surprising, then, that rest of his career: ‘Animate the Material’, ‘Even More Hazardous’, a major overview -

Teacher Resource

Jean Dubuffet Brutal Beauty Teachers’ Resource 1 Jean Dubuffet, Landscape with Argus (Paysage aux argus), August 1955, Collection Fondation Dubuffet, Paris © 2021 ADAGP, Paris/DACS, London Using this Resource Contents List Introducing Dubuffet This Teachers’ Resource complements the Barbican Art Gallery exhibition Jean Dubuffet: Brutal Beauty but can also be used for Street Art exploring both the work of Jean Dubuffet and Art Brut artists Alchemy and Enchantment without visiting the exhibition in person. This resource is: Art Brut • Divided into thematic sections that reflect key aspects of Dubuffet’s Bodies and Landscapes creative life and work. These sections can be used as starting points for the Fantastical Creatures exploration of thoughts and ideas centred on Dubuffet’s work, with example questions for discussion with students. Inspired by Dubuffet’s endlessly playful Doodles and Parallel Universes and experimental spirit, each section includes ideas for students’ own creative Examples of further resources work, self-expression and imaginative enquiry – as Dubuffet believed, an artist can be anyone who can communicate their feelings or ideas well. • Has Ask and Explore sections that give questions and creative Your Visit activities to explore in the Gallery itself or in the classroom. Art Gallery, Barbican Centre Mon 17 May–Sun 22 Aug 2021 • Aimed at primary and secondary school teachers, further 10am–7pm daily education tutors, and leaders of arts and youth groups. It is appropriate for Key Stages 2–5 with links across the curriculum including Entry to Barbican Art Gallery is free for all students in Key Stages Art and Design (in particular), Literacy, PSHE, Citizenship, 1-3. -

Jean Dubuffets Art Brut.! the Origins of the Collection

Pascal-Désir Maisonneuve (1863 – 1934), Der Tartar, zw. 1927 und 1928, Assemblage verschiedener Muschelschalen, Foto: Claude Bornand, AN, Collection de l‘Art Brut, Lausanne Claude Bornand, AN, Collection de l‘Art Muschelschalen, Foto: verschiedener 1927 und 1928, Assemblage zw. (1863 – 1934), Der Tartar, Maisonneuve Pascal-Désir jean dubuffets art brut.! the origins of the collection January 25, 2017 – July 2, 2017 An exhibition by the press contact: Mag.a Edith Wildmann museum gugging Am Campus 2 3400 Maria Gugging T: +43 664 60499 374 e-mail: [email protected] www.gugging.at [jean dubuffets art brut.! the origins of the collection jean dubuffets art brut.! the origins of the collection An exhibition by the Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne curator: Sarah Lombardi scientific collaboration: Jean Dubuffet rue de Vaugirard, ca 1946, Photo: © J. Astrid Berglund Cordier /Archives Fondation Dubuffet, Paris PRESS BREAKFAST: January 25, 2017, 10 a.m. OPENING: January 25, 2017, 7 p.m. with curator Sarah Lombardi (Collection de l‘Art Brut, Lausanne) DURATION: January 25 – July 2, 2017 Real art is always there where it is not expected! (Jean Dubuffet) 1945 marked the end of the Second World War and the beginning of a second moder- nism. At this point in time Jean Dubuffet – one of the most imaginative minds of the twentieth century – was tired of established art and went in search of a new concept of art: free, unbiased, anti-intellectual, and raw – it should be “brut”. And Dubuffet would indeed find it in unexpected places: on the street, in prisons, in folkart, and in psych- iatric clinics in Europe and abroad. -

Teaching Gallery Picturing Narrative: Greek Mythology in the Visual Arts

list of Works c Painter andré racz (Greek, Attic, active c. 575–555 BC) (American, b. Romania, 1916–1994) after giovanni Jacopo caraglio Siana Cup, 560–550 BC Perseus Beheading Medusa, VIII, 1945 Teaching gallery fall 2014 3 5 1 1 (Italian, c. 1500/1505–1565) Terracotta, 5 /8 x 12 /8" engraving with aquatint, 7/25, 26 /8 x 18 /4" after rosso fiorentino gift of robert Brookings and charles University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1946 (Italian, 1494–1540) Parsons, 1904 Mercury, 16th century (after 1526) Marcantonio raimondi 1 Pen and ink wash on paper, 10 /8 x 8" ca Painter (Italian, c. 1480–c. 1530) gift of the Washington University (Greek, South Italian, Campanian) after raphael Department of art and archaeology, 1969 Bell Krater, mid-4th century BC (Italian, 1483–1520) 1 5 Terracotta, 17 /2 x 16 /8" Judgment of Paris, c. 1517–20 3 15 after gustave Moreau gift of robert Brookings and charles engraving, 11 /8 x 16 /16" Picturing narrative: greek (French, 1826–1898) Parsons, 1904 gift of J. lionberger Davis, 1966 Jeune fille de Thrace portant la tête d’Orphée (Thracian Girl Carrying the alan Davie school of orazio fontana Mythology in the visual arts Head of Orpheus), c. 1865 (Scottish, 1920–2014) (Italian, 1510–1571) 1 1 Oil on canvas, 39 /2 x 25 /2" Transformation of the Wooden Horse I, How Cadmus Killed the Serpent, c. 1540 7 5 University purchase, Parsons Fund, 1965 1960 Maiolica, 1 /8 x 10 /8" 1 1 Oil on canvas, 60 /8 x 72 /4" University purchase, elizabeth northrup after Marcantonio raimondi gift of Mr. -

Parigi a Torino

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO Humanae Litterae DIPARTIMENTO Beni Culturali e Ambientali CURRICULUM Storia e critica dei beni artistici e ambientali XXV ciclo TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA Parigi a Torino Storia delle mostre “Pittori d’Oggi. Francia-Italia” L-Art/03 L-Art/04 Dottorando Luca Pietro Nicoletti Matricola n. R08540 TUTOR Ch.mo prof.re Antonello Negri COORDINATORE DEL DOTTORATO Ch.mo prof.re Gianfranco Fiaccadori A.A. 2011/2012 Luca Pietro Nicoletti, Parigi a Torino. Storia delle mostre “Pittori d’Oggi. Francia-Italia” tesi di dottorato di ricerca in storia dei beni artistici e ambientali (Milano, Università degli Studi, AA. 2011/2012, XXV ciclo), tutor prof. Antonello Negri. 2 Luca Pietro Nicoletti, Parigi a Torino. Storia delle mostre “Pittori d’Oggi. Francia-Italia” tesi di dottorato di ricerca in storia dei beni artistici e ambientali (Milano, Università degli Studi, AA. 2011/2012, XXV ciclo), tutor prof. Antonello Negri. Ringraziamenti L’invito a studiare le vicende di “Francia-Italia” viene da Paolo Rusconi e Zeno Birolli, che ringrazio, insieme ad Antonello Negri, che in qualità di tutor ha seguito lo svolgimento delle ricerche. Anche la ricerca più solitaria si giova dell’aiuto di persone diverse, che ne hanno condiviso in parte più o meno estesa i contenuti e le riflessioni. In questo caso, sono riconoscente, per consigli, segnalazioni e discussioni avute intorno a questi temi, a Erica Bernardi, Virginia Bertone, Claudio Bianchi, Silvia Bignami, Alessandro Botta, Benedetta Brison, Lorenzo Cantatore, Barbara Cinelli, Enrico Crispolti, Alessandro Del Puppo, Giuseppe Di Natale, Serena D’Italia, Micaela Donaio, Jacopo Galimberti, Giansisto Gasparini, Luciana Gentilini, Maddalena Mazzocut- Mis, Stefania Navarra, Riccardo Passoni, Viviana Pozzoli, Marco Rosci, Cristina Sissa, Beatrice Spadoni, Cristina Tani, Silvia Vacca, Giorgio Zanchetti. -

The Metamorphosis in Jean Dubuffet's Artworks

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 13, Issue 3, 2020 The Metamorphosis in Jean Dubuffet's Artworks Mohsen Reda Al-kizwinia*, Hassanein Abdulameer Rashedb, Bahaa A. Al- Saadic, a,b,cCollege of Fine Arts, University of Babylon-Iraq, Email: a*[email protected] This study presents the metamorphosis in the works of art by Jean Dubuffet, as a concept focussed on structuralism in its propositions. The study was interested in theorists of postmodernism art because of its strategic importance in the design process, in the aesthetics of modern art. The concept is discussed in different branches of knowledge, such as linguistics, philosophy, and art. Therefore, the syntactic structures stated that each cognitive system is made up of infrastructures called deep structures. The deep structure establishes the main bases of transformation that is referred to as generative grammar by Noam Chomsky. Meanwhile, in the branch of philosophy, Kevin Vanhoozer distinguished pre- and post-modernism by referring to what each of them considered, ‘the first philosophy’. The first pre-modernism philosophy was metaphysical, but everything in modernism turned towards epistemology. Then, in post-modernism, philosophy turned into a breakup and dismantling of epistemology. Jean Dubuffet's artworks have presented the formal transformations of elements and relationships at the aesthetic level. He created numerous artworks in different methods and using different technical experiences in drawing. He also knew how to use his tools and yield his tools to be obedient with his ideas, taking advantage of casual, emergency, and fondness of children's arts, and the insane arts. -

Fauvism Was the First Twentieth Century Movement in Modern Art

QUICK VIEW: Synopsis Fauvism was the first twentieth century movement in modern art. Inspired by the examples of van Gogh, Gauguin, and Neo-Impressionists such as Seurat and Signac, it grew out of a loosely allied group of French painters with shared interests. Henri Matisse was eventually recognized as the leader of Les Fauves, or The Wild Beasts as they were called in French, and like the group, he emphasized the use of intense color as a vehicle for describing light and space, but also for communicating emotion. The style proved to be an important precursor to Expressionism, and an inspiration for other, painterly modes of abstraction. Key Points • Fauvism never developed into a coherent movement in the manner of Impressionism or Surrealism, but instead grew from the work of several acquaintances who shared common enthusiasms. Many, such as Matisse, Marquet, and Rouault, had been pupils of the Symbolist Gustave Moreau, and admired his stress on personal expression. • The Fauves generally rejected the fantastic imagery of the Post-Impressionists, and returned to the more traditional subjects once favored by the Impressionists, such as landscapes, cityscapes, and scenes of bourgeois leisure. • Rather than extend the quasi-scientific investigations of artists such as Seurat and Signac, Fauves such as Matisse and Derain were inspired by them to employ pattern and contrasting colors for the purposes of expression. • The Fauves became renowned for using pure and unmixed colors which they intensified further by applying thick daubs and smears. • Although the Fauves were not well-versed in academic color theory, they sought out © The Art Story Foundation – All rights Reserved For more movements, artists and ideas on Modern Art visit www.TheArtStory.org unique and unnatural color combinations in their paintings with the purpose of evoking a variety of emotional responses; in that sense, color was used arbitrarily and was subject to the painter's own emotional response to the canvas. -

Paul Poiret Garment Photographs, 1925-1927

Paul Poiret garment photographs, 1925-1927 Finding aid prepared by Celia Hartmann This finding aid was generated using Archivists' Toolkit on March 09, 2018 The Costume Institute's Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library The Metropolitan Museum of Art 1000 Fifth Avenue New York, NY, 10028 [email protected] Paul Poiret garment photographs, 1925-1927 Table of Contents Summary Information .......................................................................................................3 Historical note..................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents note.....................................................................................................4 Arrangement note................................................................................................................ 5 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 5 Related Materials .............................................................................................................. 5 Controlled Access Headings............................................................................................... 6 Collection Inventory............................................................................................................7 - Page 2 - Paul Poiret garment photographs, 1925-1927 Summary Information Repository The Costume Institute's Irene Lewisohn Costume Reference Library -

Paris Avant-Garde

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE | 9 OCTOBER 2020 PARIS AVANT-GARDE NOW AVAILABLE TO BROWSE ONLINE CHRISTIE’S 20th CENTURY: LONDON TO PARIS SERIES 22 OCTOBER 2020 AUCTION HIGHLIGHTS PIERRE SOULAGES, PEINTURE Pierre Soulages will be the highlight of the Paris Avant- Garde sale with a real masterpiece executed in 1961 and coming from the personal collection of Donald & Jean Stralem, two major American collectors who acquired the painting the same year of its execution. This important large-scale painting has never been seen on the market since its purchase in 1961. It is a great chance for international collectors to discover this masterpiece by the artist. The early 1960’s were decisive for Pierre Soulages. First, because he and his wife moved to Sète where his work evolved dramatically and second because Soulages gained in notoriety thanks to two major exhibitions organized in 1960. Peinture 162 x 130 cm, 9 juillet 1961, estimated at €6,000,000-8,000,000 is a real rediscovery for the art market. ZAO WOU-KI, 31.07.68 Christie’s will also present 31.07.68 by Zao Wou-Ki. This painting was realised by the artist a few years before his wife’s passing which brought him a lot of suffering. The artist materialized his torment on the canvas as seen here and it depicts the chaos inside of him. The genius of the painter, however, lies in his ability to transcend this intimate dimension. Zao Wou-Ki's revolution, which fuses the spontaneity of Western painting with the mastery of Chinese calligraphy, explores the expressive possibilities offered by abstraction and opens up a new world of representation.