Teaching Gallery Picturing Narrative: Greek Mythology in the Visual Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Incisioni, Richiestissime Da Un Mercato Molto Fiorente, Giunge Ora Una Rassegna Di Rilevante Interesse, Che Si Apre Oggi Alle 17 Nei Saloni Della Biblioteca Palatina

Parmigianino e l’incisione <Padre dell'acquaforte italiana> l'ha definito Mary Pittaluga. E Giovanni Copertini ha specificato <Sebbene non si possa più considerare come l'inventore della tecnica dell'acquaforte, pure è da esserne stimato il creatore spirituale ché, con le sue stampe, ha insegnato agli artisti a trasfondere luce d'idealità in poche linee e in un tenue motivo di segni incrociati>. E' questo il lato meno noto del Parmigianino: incantevole pittore, straordinario disegnatore e anche abilissimo incisore; una caratteristica, quella di grafico, che nella grandiosa mostra allestita per celebrare il quinto centenario della nascita dell'artista passa un po' inosservata di fronte alla parata affascinante dei dipinti e dei disegni. Ad illuminare questo aspetto non secondario dell'attività del Parmigianino sia come autore diretto sia soprattutto come fornitore di disegni da trasformare in incisioni, richiestissime da un mercato molto fiorente, giunge ora una rassegna di rilevante interesse, che si apre oggi alle 17 nei saloni della Biblioteca Palatina (fino al 27 settembre) e che ha come titolo <Parmigianino tradotto. La fortuna di Francesco Mazzola nelle stampe di riproduzione tra il Cinquecento e l'Ottocento>. La correda un catalogo, pubblicato dalla Silvana Editoriale, comprendente la presentazione del direttore della Biblioteca Leonardo Farinelli, un approfondito saggio critico di Massimo Mussini e un'introduzione alle schede di Grazia Maria de Rubeis, responsabile del gabinetto delle stampe; il volume documenta tutte le incisioni <parmigianinesche> posseduta dalla Palatina, comprese quelle non esposte, cosicché assume un notevole valore scientifico in un settore ancora scarsamente esplorato con sistematicità. E' a Roma, dove si trasferisce nel 1524, che Francesco Mazzola entra nell'ambiente degli incisori fornendo disegni a Ugo da Carpi, considerato il padre della silografia, e a Jacopo Caraglio, incisore a bulino allievo di Marco Antonio Raimondi. -

The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

This PDF is a selection from a published volume from the National Bureau of Economic Research Volume Title: Conceptual Revolutions in Twentieth-Century Art Volume Author/Editor: David W. Galenson Volume Publisher: Cambridge University Press Volume ISBN: 978-0-521-11232-1 Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/gale08-1 Publication Date: October 2009 Title: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Author: David W. Galenson URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c5785 Chapter 2: The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century Introduction The masters, truth to tell, are judged as much by their influence as by their works. Emile Zola, 18841 Important artists are innovators: they are important because they change the way their successors work. The more widespread, and the more profound, the changes due to the work of any artist, the greater is the importance of that artist. Recognizing the source of artistic importance points to a method of measuring it. Surveys of art history are narratives of the contributions of individual artists. These narratives describe and explain the changes that have occurred over time in artists’ practices. It follows that the importance of an artist can be measured by the attention devoted to his work in these narratives. The most important artists, whose contributions fundamentally change the course of their discipline, cannot be omitted from any such narrative, and their innovations must be analyzed at length; less important artists can either be included or excluded, depending on the length of the specific narrative treatment and the tastes of the author, and if they are included their contributions can be treated more summarily. -

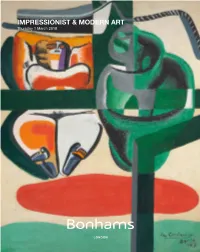

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Che Si Conoscono Al Suo Già Detto Segno Vasari's Connoisseurship In

Che si conoscono al suo già detto segno Vasari’s connoisseurship in the field of engravings Stefano Pierguidi The esteem in which Giorgio Vasari held prints and engravers has been hotly debated in recent criticism. In 1990, Evelina Borea suggested that the author of the Lives was basically interested in prints only with regard to the authors of the inventions and not to their material execution,1 and this theory has been embraced both by David Landau2 and Robert Getscher.3 More recently, Sharon Gregory has attempted to tone down this highly critical stance, arguing that in the life of Marcantonio Raimondi 'and other engravers of prints' inserted ex novo into the edition of 1568, which offers a genuine history of the art from Maso Finiguerra to Maarten van Heemskerck, Vasari focused on the artist who made the engravings and not on the inventor of those prints, acknowledging the status of the various Agostino Veneziano, Jacopo Caraglio and Enea Vico (among many others) as individual artists with a specific and recognizable style.4 In at least one case, that of the Martyrdom of St. Lawrence engraved by Raimondi after a drawing by Baccio Bandinelli, Vasari goes so far as to heap greater praise on the engraver, clearly distinguishing the technical skills of the former from those of the inventor: [...] So when Marcantonio, having heard the whole story, finished the plate he went before Baccio could find out about it to the Pope, who took infinite 1 Evelina Borea, 'Vasari e le stampe', Prospettiva, 57–60, 1990, 35. 2 David Landau, 'Artistic Experiment and the Collector’s Print – Italy', in David Landau and Peter Parshall, The Renaissance Print 1470 - 1550, New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1994, 284. -

Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum Malibu 2 (Bareiss) (25) CVA 2

CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM UNITED STATES OF AMERICA • FASCICULE 25 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, Fascicule 2 This page intentionally left blank UNION ACADÉMIQUE INTERNATIONALE CORPVS VASORVM ANTIQVORVM THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM • MALIBU Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined closed shape, and lids from neck-amphorae ANDREW J. CLARK THE J. PAUL GETTY MUSEUM FASCICULE 2 . [U.S.A. FASCICULE 25] 1990 \\\ LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA (Revised for fasc. 2) Corpus vasorum antiquorum. [United States of America.] The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu. (Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23) Fasc. 1- by Andrew J. Clark. At head of title: Union académique internationale. Includes index. Contents: fasc. 1. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured amphorae, neck-amphorae, kraters, stamnos, hydriai, and fragments of undetermined closed shapes.—fasc. 2. Molly and Walter Bareiss Collection: Attic black-figured oinochoai, lekythoi, pyxides, exaleiptron, epinetron, kyathoi, mastoid cup, skyphoi, cup-skyphos, cups, a fragment of an undetermined open shape, and lids from neck-amphorae 1. Vases, Greek—Catalogs. 2. Bareiss, Molly—Art collections—Catalogs. 3. Bareiss, Walter—Art collections—Catalogs. 4. Vases—Private collections— California—Malibu—Catalogs. 5. Vases—California— Malibu—Catalogs. 6. J. Paul Getty Museum—Catalogs. I. Clark, Andrew J., 1949- . IL J. Paul Getty Museum. III. Series: Corpus vasorum antiquorum. United States of America; fasc. 23, etc. NK4640.C6U5 fasc. 23, etc. 738.3'82'o938o74 s 88-12781 [NK4624.B37] [738.3'82093807479493] ISBN 0-89236-134-4 (fasc. -

The Renaissance Nude October 30, 2018 to January 27, 2019 the J

The Renaissance Nude October 30, 2018 to January 27, 2019 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center 1 6 1. Dosso Dossi (Giovanni di Niccolò de Lutero) 2. Simon Bening Italian (Ferrarese), about 1490 - 1542 Flemish, about 1483 - 1561 NUDE NUDE A Myth of Pan, 1524 Flagellation of Christ, About 1525-30 Oil on canvas from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg Unframed: 163.8 × 145.4 cm (64 1/2 × 57 1/4 in.) Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.) 83.PA.15 The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 154v (83.ML.115.154v) 6 5 3. Simon Bening 4. Parmigianino (Francesco Mazzola) Flemish, about 1483 - 1561 Italian, 1503 - 1540 NUDE Border with Job Mocked by His Wife and Tormented by Reclining Male Figure, About 1526-27 NUDE Two Devils, about 1525 - 1530 Pen and brown ink, brown wash, white from Prayer Book of Cardinal Albrecht of Brandenburg heightening Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment 21.6 × 24.3 cm (8 1/2 × 9 9/16 in.) Leaf: 16.8 × 11.4 cm (6 5/8 × 4 1/2 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles 84.GA.9 Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 155 (83.ML.115.155) October 10, 2018 Page 1 Additional information about some of these works of art can be found by searching getty.edu at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/ © 2018 J. -

Parigi a Torino

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI MILANO SCUOLA DI DOTTORATO Humanae Litterae DIPARTIMENTO Beni Culturali e Ambientali CURRICULUM Storia e critica dei beni artistici e ambientali XXV ciclo TESI DI DOTTORATO DI RICERCA Parigi a Torino Storia delle mostre “Pittori d’Oggi. Francia-Italia” L-Art/03 L-Art/04 Dottorando Luca Pietro Nicoletti Matricola n. R08540 TUTOR Ch.mo prof.re Antonello Negri COORDINATORE DEL DOTTORATO Ch.mo prof.re Gianfranco Fiaccadori A.A. 2011/2012 Luca Pietro Nicoletti, Parigi a Torino. Storia delle mostre “Pittori d’Oggi. Francia-Italia” tesi di dottorato di ricerca in storia dei beni artistici e ambientali (Milano, Università degli Studi, AA. 2011/2012, XXV ciclo), tutor prof. Antonello Negri. 2 Luca Pietro Nicoletti, Parigi a Torino. Storia delle mostre “Pittori d’Oggi. Francia-Italia” tesi di dottorato di ricerca in storia dei beni artistici e ambientali (Milano, Università degli Studi, AA. 2011/2012, XXV ciclo), tutor prof. Antonello Negri. Ringraziamenti L’invito a studiare le vicende di “Francia-Italia” viene da Paolo Rusconi e Zeno Birolli, che ringrazio, insieme ad Antonello Negri, che in qualità di tutor ha seguito lo svolgimento delle ricerche. Anche la ricerca più solitaria si giova dell’aiuto di persone diverse, che ne hanno condiviso in parte più o meno estesa i contenuti e le riflessioni. In questo caso, sono riconoscente, per consigli, segnalazioni e discussioni avute intorno a questi temi, a Erica Bernardi, Virginia Bertone, Claudio Bianchi, Silvia Bignami, Alessandro Botta, Benedetta Brison, Lorenzo Cantatore, Barbara Cinelli, Enrico Crispolti, Alessandro Del Puppo, Giuseppe Di Natale, Serena D’Italia, Micaela Donaio, Jacopo Galimberti, Giansisto Gasparini, Luciana Gentilini, Maddalena Mazzocut- Mis, Stefania Navarra, Riccardo Passoni, Viviana Pozzoli, Marco Rosci, Cristina Sissa, Beatrice Spadoni, Cristina Tani, Silvia Vacca, Giorgio Zanchetti. -

News Release

NEWS RELEASE FOURTH STREET AT CONSTITUTION AVENUE NW WASHINGTON DC 20565 . 737-4215/842-6353 CONTACT: Dena Crosson Laura Carter (202) 842-6353 ** FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE PRESS PREVIEW: Tuesday, Oct. 20, 1987 11:00 a.m. - 2:00 p.m. THE ART OF ROSSQ FIORENTINO TO OPEN AT NATIONAL GALLERY First U.S. Exhibition Ever Devoted Solely to 16th-century Italian Renaissance Artist October 1, 1987 - The first exhibition in the United States ever devoted solely to the works and designs of 16th-century Italian Renaissance artist Rosso Florentine opens Oct. 25 at the National Gallery of Art's West Building. Rosso Fiorentino Drawings, Prints and Decorative Arts consists of 117 objects, including 28 drawings by Rosso, 80 prints after his compositions, majolica and enamel platters, and tapestries made from his designs. On view through Jan. 3, 1988, the exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities. Giovanni Battista di Jacopo (1494-1540), best known as Rosso Fiorentino, worked in Florence from 1513 until 1524, when he went to Rome. He left the city during the infamous Sack of Rome in 1527, wandering about Italy until 1530, when he went to France to work for King Francis I at Fontainebleau. Rosso began his career with a style modeled on the art of the Florentine Renaissance, but he is now seen as one of the founders of the anticlassical style called Mannerism. An intense and eccentric individual, Rosso was internationally famous in the 16th century while today he is most readily recognized for his work at Fontainebleau and for the great impact of his Italian style on French art. -

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(S): W

Titian's Later Mythologies Author(s): W. R. Rearick Source: Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 17, No. 33 (1996), pp. 23-67 Published by: IRSA s.c. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1483551 . Accessed: 18/09/2011 17:13 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. IRSA s.c. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Artibus et Historiae. http://www.jstor.org W.R. REARICK Titian'sLater Mythologies I Worship of Venus (Madrid,Museo del Prado) in 1518-1519 when the great Assunta (Venice, Frari)was complete and in place. This Seen together, Titian's two major cycles of paintingsof mytho- was followed directlyby the Andrians (Madrid,Museo del Prado), logical subjects stand apart as one of the most significantand sem- and, after an interval, by the Bacchus and Ariadne (London, inal creations of the ItalianRenaissance. And yet, neither his earli- National Gallery) of 1522-1523.4 The sumptuous sensuality and er cycle nor the later series is without lingering problems that dynamic pictorial energy of these pictures dominated Bellini's continue to cloud their image as projected -

Downloaded from Brill.Com09/27/2021 05:43:45AM Via Free Access Brill’S Studies on Art, Art History, and Intellectual History

Sculpture in Print, 1480–1600 Anne Bloemacher, Mandy Richter, and Marzia Faietti - 9789004445864 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 05:43:45AM via free access Brill’s Studies on Art, Art History, and Intellectual History General Editor Walter S. Melion (Emory University) volume 52 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsai Anne Bloemacher, Mandy Richter, and Marzia Faietti - 9789004445864 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 05:43:45AM via free access Sculpture in Print, 1480–1600 Edited by Anne Bloemacher, Mandy Richter and Marzia Faietti LEIDEN | BOSTON Anne Bloemacher, Mandy Richter, and Marzia Faietti - 9789004445864 Downloaded from Brill.com09/27/2021 05:43:45AM via free access Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bloemacher, Anne, 1980– editor. | Richter, Mandy, editor. | Faietti, Marzia, editor. Title: Sculpture in Print, 1480–1600 / edited by Anne Bloemacher, Mandy Richter and Marzia Faietti. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2021] | Series: Brill’s studies on art, art history, and intellectual history, 1878–9048 ; volume 52 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2020055961 (print) | LCCN 2020055962 (ebook) | ISBN 9789004421509 (hardback) | ISBN 9789004445864 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Sculpture in art. | Prints, Renaissance—Themes, motives. Classification: LCC NE962.S38 S38 2021 (print) | LCC NE962.S38 (ebook) | DDC 769—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055961 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020055962 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”. See and download: brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1878-9048 ISBN 978-90-04-42150-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-44586-4 (e-book) Copyright 2021 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

VII Signatures, Attribution and the Size and Organisation of Workshops

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC) Stissi, V.V. Publication date 2002 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stissi, V. V. (2002). Pottery to the people. The producttion, distribution and consumption of decorated pottery in the Greek world in the Archaic period (650-480 BC). General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:04 Oct 2021 VII Signatures, attribution and the size and organisation of workshops 123 VII.1 Signatures, cooperation and specialisation The signatures tell us something about more than only the personal backgrounds of potters and painters, individually or as a group. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Athenian little-master cups Heesen, P. Publication date 2009 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Heesen, P. (2009). Athenian little-master cups. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:01 Oct 2021 2. XENOKLES, XENOKLES PAINTER, MULE PAINTER, PAINTER OF THE DEEPDENE CUP, POTTER AND PAINTER OF LONDON B 425 (nos. 50-92; pls. 13-27) Introduction Of the 41 cups and fragments with Xenokles’ epoiesen-signatures, 27 were known to J.D. Beazley, who assigned them to the potter Xenokles and recognized the hand of the so-called Xenokles Painter on most of them.254 Since then, another nine lip-cups and five band-cups can be added.255 Moreover, two unsigned lip-cups attributed to the Mule Painter can also be considered products of the potter Xenokles.