The Greatest Artists of the Twentieth Century

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art by Adam Mccauley

The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art The Origins and Meanings of Non-Objective Art Adam McCauley, Studio Art- Painting Pope Wright, MS, Department of Fine Arts ABSTRACT Through my research I wanted to find out the ideas and meanings that the originators of non- objective art had. In my research I also wanted to find out what were the artists’ meanings be it symbolic or geometric, ideas behind composition, and the reasons for such a dramatic break from the academic tradition in painting and the arts. Throughout the research I also looked into the resulting conflicts that this style of art had with critics, academia, and ultimately governments. Ultimately I wanted to understand if this style of art could be continued in the Post-Modern era and if it could continue its vitality in the arts today as it did in the past. Introduction Modern art has been characterized by upheavals, break-ups, rejection, acceptance, and innovations. During the 20th century the development and innovations of art could be compared to that of science. Science made huge leaps and bounds; so did art. The innovations in travel and flight, the finding of new cures for disease, and splitting the atom all affected the artists and their work. Innovative artists and their ideas spurred revolutionary art and followers. In Paris, Pablo Picasso had fragmented form with the Cubists. In Italy, there was Giacomo Balla and his Futurist movement. In Germany, Wassily Kandinsky was working with the group the Blue Rider (Der Blaue Reiter), and in Russia Kazimer Malevich was working in a style that he called Suprematism. -

Current Issues in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and Its Non-Traditional Materials

Sotheby's Institute of Art Digital Commons @ SIA MA Theses Student Scholarship and Creative Work 2018 Current Issues in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and its Non-traditional Materials Sandra Hong Sotheby's Institute of Art Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Contemporary Art Commons, Interactive Arts Commons, and the Interdisciplinary Arts and Media Commons Recommended Citation Hong, Sandra, "Current Issues in the Conservation of Contemporary Art and its Non-traditional Materials" (2018). MA Theses. 15. https://digitalcommons.sia.edu/stu_theses/15 This Thesis - Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship and Creative Work at Digital Commons @ SIA. It has been accepted for inclusion in MA Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ SIA. For more information, please contact [email protected]. High or Low? The Value of Transitional Paintings by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko Monica Peacock A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the Master’s Degree in Art Business Sotheby’s Institute of Art 2018 12,043 Words High or Low? The Value of Transitional Paintings by Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko By: Monica Peacock Abstract: Transitional works of art are an anomaly in the field of fine art appraisals. While they represent mature works stylistically and/or contextually, they lack certain technical or compositional elements unique to that artist, complicating the process for identifying comparables. Since minimal research currently exists on the value of these works, this study sought to standardize the process for identifying transitional works across multiple artists’ markets and assess their financial value on a broad scale through an analysis of three artists: Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, and Mark Rothko. -

A Southern California Visionary with Northern Michigan Sensibilities

John Lautner By Melissa Matuscak A SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA VISIONARY WITH NORTHERN MICHIGAN SENSIBILITIES 32 | MICHIGAN HISTORY Architect John Lautner would have turned 100 years old on July 16, 2011. Two museums in his hometown of Marquette recently celebrated this milestone with concurrent exhibits. The DeVos Art Museum at Northern Michigan University focused on a professional career that spanned over 50 years and the Marquette Regional History Center told the story of the Lautner family. Combined, they demonstrated how in!uential his family and his U.P. upbringing were to Lautner’s abilities and his eye for design. nyone who has lived in the Upper Peninsula tends to develop a deeper awareness of nature, if only to anticipate the constantly changing weather. !e natural landscapes, and especially Lake Superior, are integral to the way of life in the region in both work and leisure. John Lautner’s idyllic childhood in Marquette stirred what By Melissa Matuscak would become an ongoing quest to create unity between nature and architecture. !e story of what made John Lautner a visionary architect begins with his parents. His father, John Lautner Sr., was born in 1865 near Traverse City, the son of German immigrants. !ough he began school late—at age 15—by age 32 John Sr. had received bachelor’s and master’s degrees in German literature from the University of Michigan. His studies took him to the East Coast and to Europe, but he eventually returned to Michigan to accept a position at Northern State Normal School (now Northern Michigan University) in Marquette in 1903. -

The Effect of War on Art: the Work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2010 The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko Elizabeth Leigh Doland Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Doland, Elizabeth Leigh, "The effect of war on art: the work of Mark Rothko" (2010). LSU Master's Theses. 2986. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/2986 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF WAR ON ART: THE WORK OF MARK ROTHKO A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Arts in The Interdepartmental Program in Liberal Arts by Elizabeth Doland B.A., Louisiana State University, 2007 May 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT…………………………………………………………………iii CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION……………………………………………........1 2 EARLY LIFE……………………………………………………....3 Yale Years……………………………………………………6 Beginning Life as Artist……………………………………...7 Milton Avery…………………………………………………9 3 GREAT DEPRESSION EFFECTS………………………………...13 Artists’ Union………………………………………………...15 The Ten……………………………………………………….17 WPA………………………………………………………….19 -

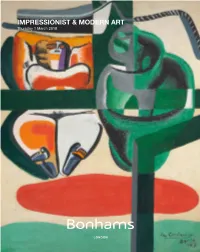

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960S

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 1988 The Politics of Experience: Robert Morris, Minimalism, and the 1960s Maurice Berger Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1646 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. -

California State University, Northridge Exploitation

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE EXPLOITATION, WOMEN AND WARHOL A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art by Kathleen Frances Burke May 1986 The Thesis of Kathleen Frances Burke is approved: Louise Leyis, M.A. Dianne E. Irwin, Ph.D. r<Iary/ Kenan Ph.D. , Chair California State. University, Northridge ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Dr. Mary Kenon Breazeale, whose tireless efforts have brought it to fruition. She taught me to "see" and interpret art history in a different way, as a feminist, proving that women's perspectives need not always agree with more traditional views. In addition, I've learned that personal politics does not have to be sacrificed, or compartmentalized in my life, but that it can be joined with a professional career and scholarly discipline. My time as a graduate student with Dr. Breazeale has had a profound effect on my personal life and career, and will continue to do so whatever paths my life travels. For this I will always be grateful. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In addition, I would like to acknowledge the other members of my committee: Louise Lewis and Dr. Dianne Irwin. They provided extensive editorial comments which helped me to express my ideas more clearly and succinctly. I would like to thank the six branches of the Glendale iii Public Library and their staffs, in particular: Virginia Barbieri, Claire Crandall, Fleur Osmanson, Nora Goldsmith, Cynthia Carr and Joseph Fuchs. They provided me with materials and research assistance for this project. I would also like to thank the members of my family. -

Lost in Translation: Phenomenology and Mark Rothko's Writings

Lost in translation: Phenomenology and Mark Rothko’s writings Evelien Boesten s4284720 M. Gieskes 09-08-2017 Table of contents: 1. Introduction 2 2. Phenomenology and its relation to art as described by Crowther 7 3. Mark Rothko I. Life and art 15 II. Rothko’s writings on art 21 III. Rothko and Crowther: a new approach to Rothko and phenomenology 31 4. Previous essays on phenomenology and Rothko I. Dahl 43 II. Svedlow 46 III. Comparison and differences: Dahl, Svedlow versus Rothko & Crowther 48 5. Conclusion 50 6. Bibliography 52 7. Image Catalogue 53 1 1. Introduction Imagine seeing a painting by Mark Rothko (1903-1970), such as Untitled (1949, fig. 1) in an art museum. Typically, Rothko’s work will be viewed in ‘white cube’ museums, such as the modern section of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, where Untitled (1949) resides. The room consists of simple white walls and wooden floors. The painting’s title tells you nothing but the fact that it has none. There is no shortcut to the painting’s subject to be found in its given name, and we are expected to go in significantly less biased because of the title’s absence.1 We stand before the painting, no title or picture frame between us and the canvas. Rothko wanted the interaction between the artist and the viewer to be as direct as possible, so he tried to eliminate as many external factors as he could (such as picture frames or titles).2 In Untitled (1949), the artist – Rothko – brought colour and form to this interacttion, while the viewers are expected to bring themselves and all that they know and are.3 A large yellow rectangle serves as the background to the other coloured rectangles that are brown, orange, purple, black and a semi-transparent green, which appear to float in front of it.4 These smaller rectangles do not only relate to the yellow background, but to each other as well. -

Grade Four Session One – the Theme of Modernism

Grade Four Session One – The Theme of Modernism Fourth Grade Overview: In a departure from past years’ programs, the fourth grade program will examine works of art in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art in preparation for and anticipation of a field trip in 5th grade to MoMA. The works chosen are among the most iconic in the collection and are part of the teaching tools employed by MoMA’s education department. Further information, ideas and teaching tips are available on MoMA’s website and we encourage you to explore the site yourself and incorporate additional information should you find it appropriate. http://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning! To begin the session, you may explain that the designation “Modern Art” came into existence after the invention of the camera nearly 200 years ago (officially 1839 – further information available at http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/dagu/hd_dagu.htm). Artists no longer had to rely on their own hand (painting or drawing) to realistically depict the world around them, as the camera could mechanically reproduce what artists had been doing with pencils and paintbrushes for centuries. With the invention of the camera, artists were free to break from convention and academic tradition and explore different styles of painting, experimenting with color, shapes, textures and perspective. Thus MODERN ART was born. Grade Four Session One First image Henri Rousseau The Dream 1910 Oil on canvas 6’8 1/2” x 9’ 9 ½ inches Collection: Museum of Modern Art, New York (NOTE: DO NOT SHARE IMAGE TITLE YET) Project the image onto the SMARTboard. -

TASCHEN Publishing House Bundles Logistics at Arvato

TASCHEN Publishing House implements new logistics concept together with VVA TASCHEN Publishing House bundles logistics at Sonja Groß Arvato Head of Marketing & Communications Arvato Supply Chain Solutions August 12, 2020 Phone: +49 5241 80-41897 Gütersloh - VVA has won TASCHEN Verlag as a new customer at its [email protected] Gütersloh location. The publishing house is combining the move to the Arvato subsidiary, which began on July 1, 2020, with a reorganization of its international logistics concept. TASCHEN and the VVA are jointly optimizing the international supply chain. The core of the new concept is centralization at a European central warehouse at the Gütersloh location, which will gradually replace the regional warehouses existing in several countries. In the future, all customers in the European markets will be served directly from there. In addition, the publishing house's international sales partners will be linked to the European central warehouse. Until further notice, „KNV Zeitfracht“ will continue to supply the German-speaking book market. "I am very pleased that TASCHEN Publishing House has chosen us for this demanding project," says Stephan Schierke, President VVA. "Outside the usual VVA industry solution, we have worked with TASCHEN to develop tailor-made logistics for the world market. Arvato's cross-industry know-how will be of benefit to us in overcoming the special challenges in terms of logistics and IT". "The new solution will reduce our complexity, lower costs through synergy and economies of scale, and improve our service," said TASCHEN-COO Hans-Peter Kübler. "The prerequisite for such a challenging project is a strong and reliable partner, which we have found in the VVA. -

Teaching Gallery Picturing Narrative: Greek Mythology in the Visual Arts

list of Works c Painter andré racz (Greek, Attic, active c. 575–555 BC) (American, b. Romania, 1916–1994) after giovanni Jacopo caraglio Siana Cup, 560–550 BC Perseus Beheading Medusa, VIII, 1945 Teaching gallery fall 2014 3 5 1 1 (Italian, c. 1500/1505–1565) Terracotta, 5 /8 x 12 /8" engraving with aquatint, 7/25, 26 /8 x 18 /4" after rosso fiorentino gift of robert Brookings and charles University purchase, Kende Sale Fund, 1946 (Italian, 1494–1540) Parsons, 1904 Mercury, 16th century (after 1526) Marcantonio raimondi 1 Pen and ink wash on paper, 10 /8 x 8" ca Painter (Italian, c. 1480–c. 1530) gift of the Washington University (Greek, South Italian, Campanian) after raphael Department of art and archaeology, 1969 Bell Krater, mid-4th century BC (Italian, 1483–1520) 1 5 Terracotta, 17 /2 x 16 /8" Judgment of Paris, c. 1517–20 3 15 after gustave Moreau gift of robert Brookings and charles engraving, 11 /8 x 16 /16" Picturing narrative: greek (French, 1826–1898) Parsons, 1904 gift of J. lionberger Davis, 1966 Jeune fille de Thrace portant la tête d’Orphée (Thracian Girl Carrying the alan Davie school of orazio fontana Mythology in the visual arts Head of Orpheus), c. 1865 (Scottish, 1920–2014) (Italian, 1510–1571) 1 1 Oil on canvas, 39 /2 x 25 /2" Transformation of the Wooden Horse I, How Cadmus Killed the Serpent, c. 1540 7 5 University purchase, Parsons Fund, 1965 1960 Maiolica, 1 /8 x 10 /8" 1 1 Oil on canvas, 60 /8 x 72 /4" University purchase, elizabeth northrup after Marcantonio raimondi gift of Mr. -

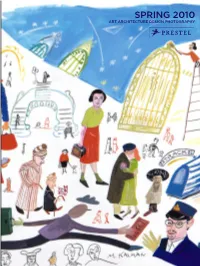

Englisch VS 1 10-7Er K.Qxd:PRESTEL VS

Maira Kalman, Next Stop, Grand Central , 1999 / © 2009 Maira Kalman PRESTEL HEAD OFFICE PRESTEL UK PRESTEL USA 978-3-7913-9845-7 ISBN-978-3-7913-9845-7 SPRING 2010 Prestel Verlag Prestel Publishing Ltd. Innovative Logistics Verlagsgruppe Random House GmbH 4 Bloomsbury Place 575 Prospect Street ART ARCHITECTURE DESIGN PHOTOGRAPHY Königinstrasse 9 London WC1A 2QA Lakewood, NJ 08701 D-80539 Munich, Germany Tel: +44 (0)20 7323-5004 Tel: (888) 463-6110 Tel: +49 (0)89 242908300 Fax: +44 (0)20 7636-8004 Fax: (877) 372-8892 Fax: +49 (0)89 242908335 e-mail:[email protected] e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] EUROPE ASIA, AFRICA GERMANY Verlegerdienst München INDIA, NEPAL, Gutenbergstrasse 1 SRI LANKA, BHUTAN TBI - Publisher & Distributors D-82205 Gilching, Germany 1882 Bhasker Bhawan Tel: +49 (0)8105 388-123 Village Kotla, Mubarkpur Fax: +49 (0)8105 388-259 New Delhi 110003 / India e-mail: [email protected] Tel: 9811791246 / 01146056198 e-mail: [email protected] AUSTRIA Mohr Morawa Buchvertrieb Sulzengasse 2 SOUTHEAST ASIA Peter Couzens A-1230 Wien Sales East Tel: +43 (0)16 68 01 45 43 Soi Pichit Fax: +43 (0)16 68 96 800 Sukhumvit Road 18 e-mail: [email protected] Klong Toei Bangkok 10110 SWITZERLAND Buchzentrum Thailand Industriestr. Ost 10 Tel + Fax: +66 2258 1305 CH-4614 Hägendorf Mobile: +66 85058 6265 Tel: +41 (0)62 209 26 26 e-mail: [email protected] Fax: +41 (0)62 209 26 27 e-mail: [email protected] CHINA, HONG KONG, KOREA, PHILIPPINES, Edward Summerson FRANCE Interart TAIWAN